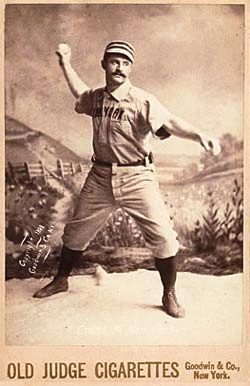

Ed Crane

Ed Crane was a big, strong guy for his era. He stood only 5 feet 10 inches tall but weighed more than 200 pounds. Much of it was muscle, at least when he was young. His nicknames reflected his stature: Big Ed, Big Ned, and Hercules. He was said to throw harder than any other pitcher in the 19th century, except perhaps Amos Rusie. For this he was dubbed Cannonball and that’s exactly what he burned into the plate. As a result, he used up one catcher after another during a time when mitts were meager at best. Crane could zip the ball past the batters. But his career was marked by wildness, and he was often among the league leaders in walks and wild pitches.

Ed Crane was a big, strong guy for his era. He stood only 5 feet 10 inches tall but weighed more than 200 pounds. Much of it was muscle, at least when he was young. His nicknames reflected his stature: Big Ed, Big Ned, and Hercules. He was said to throw harder than any other pitcher in the 19th century, except perhaps Amos Rusie. For this he was dubbed Cannonball and that’s exactly what he burned into the plate. As a result, he used up one catcher after another during a time when mitts were meager at best. Crane could zip the ball past the batters. But his career was marked by wildness, and he was often among the league leaders in walks and wild pitches.

There were many highlights in Crane’s career, at least in the first half of it. He set long-distance throwing records in the United States and abroad. He was a key factor in three consecutive pennant winners (1887-1889) in Toronto and New York. In the New York Giants’ 1889 post-season triumph over Brooklyn of the American Association, Crane was the winning pitcher in four of the Giants’ six victories. He garnered enough respect to be asked to join barnstorming tours to the West Coast, to Cuba, and around the world. Of note today, he was one of the first pitchers to wear a glove and was one of the few who played in the four major leagues of the 19th century (National League, Union Association, Player’s League, American Association).

The end of Crane’s career wasn’t pretty. His nicknames took on additional meanings because of his weight gain from excessive eating and prodigious drinking. Soon, Big Ed and Cannonball were derisive terms. He was referred to in print as Fat Boy and a few other similar jabs. Years of overeating, heavy drinking, and competing in throwing contests combined with untamed wildness on the mound to limit his effectiveness and shorten his playing career. Despite having a young wife and child, Crane never conquered the drinking or established a plan for life outside baseball. Depression crept in as he began to lose both family and career. One night, alone and penniless in a shabby hotel in Rochester, New York, on the verge of being evicted, Crane ingested too much sedative and died. Most then, and today, assumed it was a suicide.

Edward Nicholas Crane was born on May 27, 1862, in Boston to Irish-born parents James T. and Anne Crane. Edward was the youngest of ten children, six of whom were girls. His oldest sibling predated him by 20 years. James and Anne immigrated to the United States before 1840. They initially lived in Tennessee but settled in South Boston by 1844. James was a tailor, owning a lucrative business that supported his large family and provided the comforts of the day. Most of the family followed him into the trade. James died before Edward was 8 years old.

By the time Edward was in his mid-teens, he was working as a machinist. He played amateur and semipro baseball in and around South Boston. His ability to throw hard pushed him toward catching, pitching, and right field.

In 1884 a third major league, the Union Association, emerged, and one of its franchises was the Boston Reds. The team was hastily assembled in March and April, and all but one of its players were from the Boston and Providence areas. Among the several local amateurs on the roster was Crane, a backup catcher and outfielder. He appeared in 101 games. High in the statistics in many hitting categories, Crane was fourth in the league in slugging and tenth in batting. He set a major-league rookie record with 12 home runs. Starting that year, Crane participated in many throwing contests. The distance record at the time, 400 feet 7.5 inches, had been set by John Hatfield in the early 1870s. On October 12, 1884, in Cincinnati, Crane topped the mark, heaving the ball 405 feet 7 inches with the wind. The toss was never officially authenticated but for baseball’s purposes, it served as the distance to beat for years to come.

The Union Association folded after one season. Crane joined Providence in the National League in 1885 and played one game in May as an outfielder. He was released by Providence when Dupee Shaw joined the club and signed with league rival Buffalo, where he played in 13 games and had 14 hits in 51 at-bats. Still the property of Buffalo, Crane nevertheless returned home and played in six games for Brockton in the Eastern New England League. On November 19 Buffalo, in the process of folding, assigned Crane’s contract to the league. In January, the league assigned him to the expansion Washington Nationals. A few weeks later, he came to terms with the club. At 23, Crane was already having trouble with his weight. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat commented, “Ed Crane weighs over 200 pounds and will have to sweat off about fifteen pounds before he goes to Washington.” He couldn’t help himself; he just loved to eat. A teammate said Crane’s favorite meal was a dozen soft-boiled eggs served in a soup bowl followed by two dozen clams. Perhaps as a result of his weight, Crane was among the poorer players in the league in 1886. In 68 games for Washington, mostly in right field, he batted a meager .171. In ten games on the mound, he was tagged with a 1-7 record. On September 1, while losing 15-2 to Chicago, he gave up 11 hits and 14 walks, threw five wild pitches and committed an error. Three weeks later he was released. After the season, Crane joined manager Lew Simmons of the Philadelphia American Association team and his group of players who traveled to Cuba for some barnstorming contests. They left on November 6, and were scheduled to play two games a week through the end of the year. The trip was a financial disaster; only a couple of contests were played before they returned to the States on November 22.

The right-hander didn’t catch on with a major-league club in 1887; he landed with Toronto in January, signing for the highest salary in the International Association. The move permitted Crane to pitch in a regular rotation for the first time in professional baseball. Toronto took the pennant with a 65-36 record under manager Charlie Cushman. Crane shared the league lead of 33 victories, against 13 losses, with Newark’s George Stovey, the top African-American pitcher of the 19th century. At the end of the season, Crane won three games to clinch the pennant for the club. On Saturday he won both ends of a doubleheader, 15-4 and 5-4. In the second game he drove in three runs, including a game-winning home run. On Sunday he won again as Toronto romped to a 22-8 victory. Crane pulled off the extremely rare feat of also leading the league in batting average with a .428 mark. Crane traveled again after the season, joining the Philadelphia National League team for a barnstorming trip in California, mainly in San Francisco. The team played from November into the New Year.

Crane was back in the major leagues in 1888. He spent nearly the entire season with the Giants, but was used sparingly. The Hall of Fame duo of Tim Keefe and Mickey Welch handled most of the pitching assignments. Crane pitched in 12 games, one of them a late-season no-hitter, posting a 5-6 record. He did not play in the field at all, and from then until the end of his career Crane was almost exclusively a pitcher. That season Crane became one of the first pitchers to wear a glove; it was mentioned by the New York Sun on April 14. After pitching a solid game on June 6, Crane was removed from the rotation. In early July the Giants sent him to Jersey City but he returned at the end of the month and made two starts, a 4-1 complete-game victory on July 27 and a 9-1 loss three days later. In July, with Crane sitting mostly idle, the St. Louis Browns tried to secure his release but the Giants had other plans. He went back into the rotation when Tim Keefe came up lame in late September, and pitched well. On the 27th, Crane pitched a no-hitter at the Polo Grounds against Washington. He was wild, walking six batters, but only three balls made it past the infield. Six outs were grounders back to the pitcher; another five were strikeouts. The Giants won 3-0 in a game called because of darkness after seven innings. Apparently unimpressed with the significance of a no-hitter, the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean commented that “it was a tiresome contest.” On October 4, Crane pitched a 1-0, one-hit shutout over Chicago to clinch the pennant. In that game Crane became the first known major-league pitcher to strike out four men in an inning. The New York Times offered this praise: “The game can be explained very briefly. Crane, New York’s swift reserve pitcher, shot the ball across the plate so rapidly that the Chicago men could not see the sphere. Inning after inning they tried to hit safely, but they either struck out, sent up easy flies, or knocked grounders to the infielders. Only one man (Jimmy) Ryan, hit the ball safely.” In the postseason series against the American Association’s St. Louis Browns, Crane made two starts, compiling a 1-1 record. The Giants won the championship, six games to four.

Crane was a fun guy to have in the clubhouse, at least before he became consumed with alcohol in the 1890s. He was an accomplished storyteller, often regaling his teammates with stories from his travels. They would pull up a chair and listen to him reminisce well past midnight in the smoker compartment on the train. The Daily Inter Ocean observed, “He is not an educated man, but he has a rich fund of natural humor that makes him interesting.” The Galveston Daily News said, “Crane is a good dresser, though inclined to be a little ‘jack’ in his talk and manner.” Crane did in fact go out of his way to dress well. He insisted on the finest cloths and employed the best tailors.

In early October 1888, Cap Anson and Albert G. Spalding invited Crane to join their planned international barnstorming journey, the famed Spalding World Tour. It appears that Crane cultivated his drinking habit on the trip. On the 27th, he and Giants teammate John Montgomery Ward joined the group in Denver after the post-season series against St. Louis. Crane was a member of the squad that played against Anson’s Colts. After barnstorming through the West, the group sailed from San Francisco for four months of traveling and partying with a few games sprinkled here and there. They visited the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), Samoa, Australia, Ceylon, Yemen, Cairo, Italy, France, England, Scotland, and Ireland. They returned to New York on April 6. Amid the boredom of traveling, the men had some amusing moments.

The monotony of travel, ship-bound parties, and elaborate celebrations accorded them at each stop was said by contemporaries to have driven Crane to the bottle for the first time. The Daily Inter Ocean said, “Ed Crane did not know what the taste of liquor was like until he made the trip around the world. He got his start drinking wine at the banquets tendered the American tourists.” This radical change in Crane’s lifestyle surprised former major leaguer Curry Foley, who recalled a conversation he had with Crane around 1886, when Crane told him, “No sir, I never tasted liquor in my life and I don’t think I ever will”

Actually, Crane had started drinking before the tour; it just got out of hand during the trip, noticeably so. Crane began drinking heavily from the moment he joined the tour in Colorado. By the time the men reached San Francisco, he had missed several games due to drunkenness and being hung-over. He was left alone in the mornings. Even after he felt well enough to leave his room, he was said to be a man to stay away from until later in the day, perhaps after he’d had a bit of the “hair of the dog.” Adding to his miseries during the trip, Crane suffered heatstroke on the way to Australia and ended up not pitching much, instead umpiring. At times he remained on the ship because he couldn’t handle the heat on land.

Crane did have some fun. To break the monotony on the ship, Crane, an impressive tenor, spent hours on the deck entertaining the passengers with song.

He set an Australian record by throwing a cricket ball 384 feet 10.5 inches in Melbourne. An American sailor gave him a small Japanese monkey. The little beast terrorized the crew and passengers throughout the journey. A couple of particularly irate passengers informed the crew that Crane was hiding the monkey in his coat pocket. As the baseball party boarded a train at the French-Italian border to journey to France, the train crew insisted that Crane pay fare for the monkey. He initially balked but was then surrounded by soldiers, a circumstance that quickly changed his mind. Crane lugged the animal around all spring after his return to New York, claiming it was the Giants’ new mascot.

After the world tour, Crane nosedived very publicly. He fell into periods of heavy drinking and wore out his welcome with more than one manager and club owner. His weight ballooned. More than one source referred to him as “the fat boy” or some other such gibe.

Crane re-signed with New York upon his return to the States. The league dropped the number of balls required for a walk in 1889 to four. Crane knew he couldn’t waste as many pitches and decided to emphasize his fastball: “I am going (to) try speed alone this summer, under the four-ball rule, with change of pace and height of delivery as my only standbys.” Few other pitchers of the era threw harder than Crane. Tim Keefe said Crane “is the fastest of them all, and what is best has splendid curves and great command of the ball.” Most other contemporaries weren’t as generous with their assessment of his curveball; they viewed it as mediocre at best. Still, there was the control problem. The Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette said, “As a pitcher he resembles the little girl who ‘When she was good, she was very, very good, but when she was bad, she was horrid.’” Crane struck out many but the righthander was often among the league leaders in walks and wild pitches, negating the advantage of his speed and marking him as merely a so-so pitcher.

Crane made 25 starts for the Giants in 1889, posting a 14-11 record. After back-to-back starts on May 7 and 8, he was out of the rotation with an injury he suffered sliding into second base. He rejoined the team at the end of May and made a few relief appearances, then returned to the rotation on June 24. The Giants won the pennant again in 1889. Crane dominated the postseason series against the Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the American Association. He started five games, completing four, for a 4-1 record. The Giants won the series six games to three. Hank O’Day won the other two games for the champions. Crane also did well with the bat, knocking in five runs on five hits including a double, triple, and home run. His stellar work on the mound was marred only by his typical wildness; he walked 32 men in the 38 innings he pitched those five games.

On November 9, Crane was among the contingent that formed the New York club of the new Players League, an outgrowth of the Brotherhood union. He appeared in 43 games in the new league, notching a 16-19 record. Drinking took a firm hold on Crane’s life that season. From then on he was labeled as a sot. In mid-August he was arrested at 2 o’clock on a Sunday morning at a Harlem watering hole. He tangled with the police, threatening them and providing a false name. The judge fined him $10 for resisting arrest. The ballclub added another $100 to the total. With his head between his legs, Crane dried out and exercised diligently to get back into shape. It was too late in the season to make a difference. The club finished in third place, eight games out of first, with a 74-57 record. Team director Edward Talcott laid the blame squarely at Crane’s feet, saying, “All of the boys strove hard to win, but Crane appeared to be indifferent. Just when we wanted his services he was not in a fit condition to do any work, a state of affairs due to his desire to partake in intoxicating liquors. On one or two occasions he even went so far as to refuse to report for duty. … Our failure to win the pennant can only be attributed to one reason – Crane’s poor work.” The pitcher did skip a few games without permission and showed up at work drunk more than once. It also didn’t help that he walked a whopping 208 batters in 330 innings. In September, Crane agreed to play in California and Mexico with Charles Comiskey and crew over the winter; however, the trip was canceled at the end of October when the players, one by one, started to pull out. In December, he played indoor baseball with a team organized by King Kelly.

When the Players League disbanded after one season, the New York Giants expected Crane to return to their club but they couldn’t agree on salary. Crane wanted $3,000 but the Giants offered $2,500 as the league tightened its belt with the failure of the Players League. Instead, Crane signed with King Kelly, who took over the Cincinnati club in the American Association, in late March for $3,500, the most money of his career. Thus Crane became one of the few men to play in four major leagues: the National League, the American Association, the Union Association, and the Players League. He led the club in wins with a 14-14 record and led the league in ERA with a 2.45 mark. Still, he wasn’t putting forth his best effort. The Sioux County Herald commented, “Big Ed Crane has been a disorganizing element in Kelly’s team and Kelly’s rule of not fining a player under any circumstances allows Crane to do as he pleases, lose games, and draw a $3,500 salary.” The club disbanded on August 16; as a favor, Kelly gave Crane his release just before the league folded so he would be a free agent. The American Association didn’t see it that way; it assigned him to the Milwaukee club, Cincinnati’s replacement. Instead, Crane jumped across town to the National League’s Cincinnati entry, making his first appearance for the club on August 22. He replaced Hoss Radbourn, who had been given his outright release, effectively ending his major-league career. Crane appeared in 15 games for the Reds, winning 4 and losing 8.

In mid-November, Crane tentatively agreed to an invitation by the New York Giants to join the team for spring training in 1892. He was a no-show at spring training; instead he agreed to join the Boston Blues, a barnstorming club being formed by brothers John and Art Irwin. Then Crane thought better of that idea and signed with the Giants on April 6, reporting in good shape. Alternating on the mound with Amos Rusie and Silver King, Crane appeared in 47 games for the Giants, starting 42. He posted a 16-24 record. The wild trio struck out 648 batters but walked 630.

Crane married Nellie Dolan of Chicago on September 11. The couple had met about 1887 and dated for about two years. Her parents objected to their union and forced a breakup, pushing Nellie toward another suitor. She was to marry the new beau in October 1892. Crane and the Giants arrived in Chicago on September 4 to play three games. Crane went to the Marshall Field department store, where Dolan worked, and tried to win her back. On September 10, she took a train for New York, leaving a note behind telling her parents of her plans and asking for their forgiveness. On the 11th, Crane and Dolan were married in Jersey City.

The next season, 1893, was Crane’s last in the major leagues. He had to work hard just to get back into shape after eating and drinking heavily all winter. He worked out at Boston College in January and February, getting his weight down to 208. That was the season the pitching distance was pushed back to 60 feet, 6 inches. Like many others, Crane began practicing pitching at 55 feet and incrementally moved back to the new distance. The Giants saw little reason to worry about the change, believing that Rusie, King, and Crane were all strong enough “to pitch from second base.” Crane flopped, though. After seven games, he had a 2-4 record, and the Giants released him on May 19 for being out of condition. He pitched on May 21 for Brooklyn in a benefit game that raised $5,000 for Darby O’Brien, a pitcher for Boston in the American Association who was dying from tuberculosis. The Giants picked Crane up again, but released him for good after a 15-11 slugfest victory on June 14 over Chicago. The New York Times writer covering the game said, Crane “had no speed, was hit hard and was unable to get the ball over the plate.” He gave up eight runs in eight innings. He negotiated with New Orleans but ultimately signed with Brooklyn, and made starts on July 9 and July 19. He lost them both. The first game was another slugfest, a 19-8 loss to Louisville. The second was a 12-2 complete-game loss to Baltimore. Crane was released soon thereafter. Over his major-league career, Crane posted a 72-97 record with 885 bases on balls and 719 strikeouts.

Unemployed, Crane tried without success to get appointed as a league umpire; he had substituted in five games over the last two years in the National League. In August, Crane signed with Providence of the Eastern League. On August 31, he joined the Springfield club of the same league, appearing in three games with a 1-2 record. He may have also played for the league’s Wilkes-Barre team that season.

Out of shape from overeating and drinking excessively, Crane bounced around for the next couple of years. His arm had lost some speed from all those throwing competitions. He wasn’t in condition to cope with the new 60 foot 6 inch pitching distance. In early April 1894, Crane was pitching batting practice for the Harvard baseball team. He soon joined Haverhill of the New England League. He was released on May 25, was quickly called back to pitch a few more games, and then was released again on June 11. On June 24, he made his first appearance for Worcester of the same league.

On April 3, 1895, Crane signed with Toronto in the Eastern League. He appeared in 29 games, went 7-18, and was released in July. On August 18, Crane joined Rochester of the Eastern League for nine games, losing six against only two victories. At the end of the year, he re-signed with Rochester but had a sore arm in the spring and couldn’t pitch. He talked Providence and Springfield of the Eastern League into using him for a total of four games. In May and June, he umpired a few games in Providence but was fired by league president Pat Powers after numerous complaints about his incompetence and heavy drinking. At the beginning of July, he briefly joined Mark Baldwin, a former major leaguer who organized an independent club in Auburn, New York. After that Crane bounced around trying to pick up odd jobs umpiring.

Crane sank deeper into the bottle as his prospects and money quickly ran out. He became despondent, freely talking about his troubles and the grim outlook for his future wherever he went. He obtained a prescription for a sedative, liquid chloral hydrate, to help with his insomnia and perhaps his depression as well. On Saturday, September 19, 1896, the proprietor of Congress Hall, a run-down hotel in Rochester, New York, told Crane, who had been drinking heavily all day, that he would have to vacate his room the next day because he had not paid for it. At 10 o’clock the next morning the bellboy banged on the door to awaken Crane. There was no answer. A clerk then climbed through the transom and found Crane, 34, lying dead on the bed. He had overdosed on the sedative. The local coroner listed the cause of death as an “accidental death from taking a chloral prescription for nervousness.” Chloral hydrate was a strong drug, easily overdosed. It was roundly assumed that Crane had committed suicide. Mike Sullivan of the New York Giants, for one, recalled that Crane had talked about suicide with him at one time. Those who saw Crane in the weeks before his death said he freely lamented about his troubles. Reports suggested that he was depressed over the end of his playing career and the estrangement from his wife and child, who were living in her hometown of Chicago. Crane was buried in Holyhood Cemetery in Brookline, Massachusetts.

Sources

Thanks to Ray Nemec for assistance with Crane’s minor league statistics.

Ancestry.com

Atchison Champion, Kansas

Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, Maine

Boston Daily Advertiser

Boston Globe

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette

Chicago Tribune

Daily Evening Bulletin, San Francisco

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago

Daily Picayune, New Orleans

Filey, Mike. Toronto Sketches 7: The Way We Were. Ontario, Canada. Dundurn Press Ltd., 2003.

Fitchburg Sentinel, Massachusetts

Galveston Daily News

Hamilton Daily Democrat, Ohio

Lamster, Mark. Spalding’s World Tour: The Epic Adventure That Took Baseball Around the Globe and Made it America’s Game. New York: Public Affairs, 2006.

Logansport Journal, Indiana

Logansport Pharos, Indiana

Lowell Sun

Milwaukee Sentinel

Morning Oregonian, Portland

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game on the Field. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

New York Sun

New York Times

Philadelphia North American

Oshkosh Daily Northwestern, Wisconsin

Retrosheet.org

Richwood Gazette, Ohio

Rocky Mountain News, Denver

Sioux County Herald, Orange City, Iowa

Sporting Life

St. Louis Globe-Democrat

Syracuse Daily Standard

Syracuse Herald

Washington Post

Wisconsin State Register

Wright, Marshall D. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, 1998.

Full Name

Edward Nicholas Crane

Born

May 27, 1862 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

September 20, 1896 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.