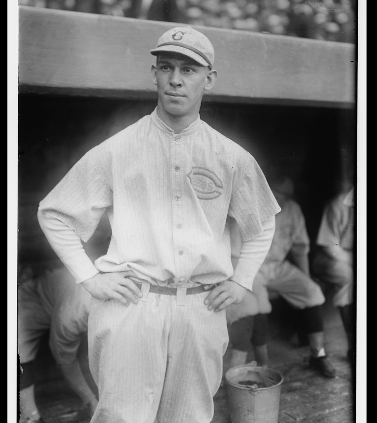

Ed Gerner

Here’s how the story goes: a young lefty pitcher in the 1910s breaks into the big leagues but as time goes on, his hitting is too good to leave him out of the lineup in between starts. He eventually blossoms into an exceptional hitting outfielder on baseball’s biggest stage, New York City.

Here’s how the story goes: a young lefty pitcher in the 1910s breaks into the big leagues but as time goes on, his hitting is too good to leave him out of the lineup in between starts. He eventually blossoms into an exceptional hitting outfielder on baseball’s biggest stage, New York City.

If you thought Babe Ruth, you’d be correct. But the story also fits another player, lesser known because he created his own baseball path rather than allowing others to chart it for him.

Eddie Gerner was all of 17 when he broke into Organized Baseball with the Albany Senators of the New York State League in 1915. By 21, he was the youngest member of the World Series champion Cincinnati Reds. But instead of remaining within Organized Baseball, Gerner jumped his contract in 1920 and played semipro ball for the rest of his career. By the late 1920s, he had transitioned into a power-hitting outfielder on one of the best semipro teams, not just in New York City, but nationally, the Brooklyn Bushwicks.

Working a day job as a clerk, Gerner commuted from Philadelphia to New York on the weekends to play for the Bushwicks. For four seasons with the Bushwicks, he played against the best semipro teams, white or black, on the East Coast. He hit over .350 in all four seasons. His combination of day job and weekend ballplaying was so lucrative that in 1928 he reportedly turned down a $5,000 signing bonus offered by Otto Miller, catcher and acting scout for the Brooklyn Robins.1

Unlike Ruth, Gerner, who stood a quarter-inch under 6-feet-1 and weighed 182 pounds,2 kept himself in great shape, playing high-level semipro baseball until he was 45. He ran a mile along railroad tracks every day during the baseball season. “You are only as young as your legs,” said Gerner.3

Edwin Frederick Gerner was born on July 22, 1897, in Philadelphia to John and Maggie Gerner. John was listed as a huckster, someone who sold small articles or even vegetables, either door to door from a cart or a small stall, in the 1900 United States census. Eddie was the youngest of eight children born to John and Maggie.

A “Gerner” shows up as a pitcher in Philadelphia Inquirer box scores as early as 1910, playing for various semipro teams in Philadelphia. By 1914 he had made a name for himself as a pitcher in the semipro ranks. He was pitching for Stetson, one of the top Philadelphia semipro teams. No doubt it was there that Gerner caught the eye of Philadelphian Patsy O’Rourke who was the manager of the Albany Senators of the Class-B New York State League for 1915.

O’Rourke thought so much of the 17-year-old Gerner that he signed him as one of his pitchers. But O’Rourke didn’t put together much of a team. Albany was by far the worst team in the league with a 33-89 record, finishing 45½ games behind regular-season champion Binghamton. Gerner went 4-22 for the last-place Senators. In addition to little support from his teammates, he tended to be wild. In one game, he walked seven in a 1-0 loss to Elmira. But Gerner often played in the outfield for Albany. In fact, in mid-August, Gerner was the Senators’ regular right fielder, taking a break from the outfield only when it was his turn to pitch. He batted a respectable .217 and set the groundwork for his transition to everyday player later in his career.

Playing for bad teams would be the norm for Gerner’s career in the minor leagues. In 1916 he played for Albany again. The team was a little better, but in midseason it moved to Reading, Pennsylvania. Gerner’s record was much better, 15-23 for the sixth-place (58-70) Albany Senators/Reading Pretzels. He also hit well, batting .285. Gerner pitched so well that the Cincinnati Reds drafted him in September.

Gerner attended 1917 spring training with the Reds and manager Christy Mathewson in Shreveport, Louisiana. Despite hitting and fielding well, he was “very wild” in a couple of games and the Reds sold him to the Montreal Royals of the International League.4

Gerner found himself on another terrible squad. The Royals finished seventh out of eight teams. However, Gerner had a brilliant season. He went 20-20, winning more than a third of the Royals’ 56 wins. His teammate, future Hall of Famer Waite Hoyt, years later remembered Gerner’s pitching prowess. “Eddie was the star of the club,” said Hoyt 25 years later, “and the only guy who could win [games].”5 After the season, Gerner was pitching again for Stetson, making some extra cash from his former employer.6 This would be a theme throughout his career.

Gerner refused to report to spring training in 1918. It was reported that Mathewson placed Gerner on the voluntary retired list, then two weeks later Mathewson was quoted as saying that he had joined the US Navy. Neither was true – Gerner was playing with Stetson again. With the United States’ entry into World War I, players were pressured to either enlist or work in a defense-industry job. In June Gerner took a job at the Hog Island Shipyard, which also meant he was pitching for Hog Island in the Delaware River Shipyard League.7

The Reds attempted to coax Gerner back but Gerner rebuffed them. Chances were he was making more money working at the shipyard than the Reds were willing to pay him. As nationally syndicated sportswriter Effie Welsh wrote about his refusal of the Reds’ offer, “Gerner has a congenial position in Philadelphia and pitches on Saturdays for semi-professional clubs.”8

Gerner continued to pitch for Hog Island throughout the summer. While many of the players around him were going to war, Gerner was still too young to be inducted. At the end of July, when he turned 21, he registered for the draft. The war ended a few months later without Gerner entering the military.9

The Reds wasted no time in getting Gerner under contract. He was among the first to be signed in 1919.10 This time the Reds, under manager Pat Moran, kept Gerner on the squad when they moved north for the season opener. But Gerner found himself to be more of a batting-practice pitcher than a contributing member of the team. Despite being on the squad for the entire season, Gerber saw action in just six games, five as a pitcher and only one as a starter. The game he started, on July 28 against the Pittsburgh Pirates, was also the only major-league game in which he registered a hit. The Reds won the game 8-7 with Gerner pitching eight innings, giving up 12 hits and seven runs (four earned) to get the win. He also helped his cause, knocking in two runs, one of them on his only hit, a double in the fifth off the Pirates’ Hal Carlson.

Gerner saw action in only two more games the rest of the season, both in mop-up roles in blowout losses. The Reds went on to win the National League pennant, then beat the Chicago White Sox in the tainted 1919 World Series. After the season, Gerner returned to his job as a clerk at Hog Island. Using his winners’ share of the World Series money, he married fellow Philadelphian Marguerite Elizabeth “Daisy” White.11

Gerner signed for the 1920 season and again made the team. But as the Reds barnstormed their way back to Cincinnati, he left the team because his father was ill. He never returned.12

For more than a month, nothing was heard from Gerner. Then reports out of western Pennsylvania indicated he was playing for the town team of Franklin, a town about 85 miles north of Pittsburgh. He and Walt Kinney, a pitcher with the Philadelphia Athletics, had been signed in late May to bolster the Franklin team.

Starting in 1919, Franklin and its rival, Oil City, raided the major leagues for players. The two towns had been playing baseball against each other since 1866. Fueled by an influx of oil money after World War I, the two teams purchased players for a rivalry that drew thousands of people every time they played each other. James Borland, president of Franklin and the managing editor of the Franklin News-Herald, wrote, “We took players from the big-league teams and paid them exorbitant prices, all made possible by the easy money people were making after the close of the war.”13

Gerner joined the Philadelphia Athletics’ Scott Perry and Tom Rogers; the Cleveland Indians’ Joe Harris; and future Philadelphia Phillies catcher Harry O’Donnell among others. The Reds didn’t pursue legal action, instead sending scout Gene McCann to Franklin to induce Gerner to come back. All it did was pad Gerner’s wallet. Franklin raised Gerner’s salary by $1,000 to keep him.14

After a slow start, Gerner pitched and hit well. In an 11-game season-ending series with Oil City, Gerner won two of Franklin’s four wins and batted .414. After the season he went back to his job as a clerk at the Stetson Hat Factory in Philadelphia.15

In 1921 Franklin offered the popular Joe Harris a salary of $6,000 for four months. Paying that much to one player, Franklin needed to cut some of its former players. Gerner was one of three players released. The Franklin team would finally dissolve halfway through the 1921 season under the burden of the huge salaries.16

Meanwhile Gerner went back to playing for semipro teams in Philadelphia. In 1921 he won 13 straight games for Fleisher Yarn before hurting his arm and losing in mid-June. After resting his arm for a couple of months, he ended the season playing for semipro teams Harrowgate and Nativity. From 1922 through 1924, Gerner played with various top Philadelphia semipro teams including South Philadelphia, Fleishers, and Germantown.

In 1925 he took his talents to New York, playing for George Lippe’s Bay Ridge club of Brooklyn, commuting on the weekends from his home in Philadelphia. For two seasons, he played for Bay Ridge and it was with Bay Ridge that Gerner transitioned to full time as an outfielder and batting fourth in their lineup.

Bay Ridge’s Brooklyn rival, the Bushwicks, took notice of the power-hitting Gerner and signed him for the 1927 season. He joined former major leaguers Stan Baumgartner and Eppie Barnes as well as the famous Hawaii-born semipro Buck Lai.

Batting cleanup, Gerner had an excellent season. Going into October’s “Little World’s Series” with the Farmers semipro club, Gerner led the team with a .374 batting average. Playing in all 49 games, Gerner pounded out 11 doubles, three triples, and four home runs. He was the only player to hit a home run for the Bushwicks that season.17

After the season, the Brooklyn Robins approached Gerner to play for them for 1928. In 1926 Gerner had been reinstated by Organized Baseball six years after jumping his contract to play with Franklin. Now, at a March meeting in Philadelphia, Gerner told Brooklyn’s Otto Miller, who had a certified check in hand for $5,000, that he’d have to think about the offer and would answer him on April 1. Bushwick teammate Howard Lohr claimed he witnessed the meeting. “It made me feel sick to see Eddie refuse that five grand,” said Lohr, adding, “If Eddie can see his way clear to leaving his business in [Philadelphia] he will join the Robins when they come North.” He never did accept the check.

Working his day job and playing for various Philadelphia semipro teams during the week and the Bushwicks on the weekend was more appealing and probably more lucrative than signing with the Robins.

Gerner played three more seasons for the Bushwicks. In 1928 he again led the team in hitting, batting .353 in 54 games.18 In 1929 Gerner had his best season yet, batting .423, best of all the regulars. He pounded out five home runs, six triples, and 13 doubles.19

With the addition of lights to the Bushwicks’ Dexter Park in 1930, their schedule increased and included weekday games. Gerner played in 63 of the Bushwicks’ 73 games and again led the team in batting with a .376 average. But the commuting had become too much. The combination of his day job as a shipping clerk at a drug manufacturing company and the travel to night games during the week for the Bushwicks was too much. The Brooklyn Citizen wrote at the end of the 1930 season, “Gerner suffered a breakdown in the last month of the season and had to give up baseball.” The Brooklyn Standard Union said he “quit due to sickness.”20

For the remainder of his playing days, Gerner stayed in the Philadelphia area. In 1931 he was a hired gun, playing for whoever paid him best. From 1932 through 1935, he played almost exclusively with the powerhouse Wentz Olney semipro team. In 1936 he hooked up with wealthy silk mill owner Oliver “Ollie” Schelly to play in the semipro Eastern Pennsylvania League. Schelly was the manager of the East Greenville team when he signed Gerner. From 1936 through 1942, wherever Schelly managed, Gerner played. Gerner played four seasons in East Greenville, then moved with Schelly in 1940 to Easton, Pennsylvania. The two then jumped to Nazareth, Pennsylvania, for the 1941 and 1942 seasons.

Gerner, who had turned 45 during the 1942 season, ended his career after the season. In the 1940 US census he was listed as a shipper working for a wholesale drug company.

After he retired from baseball, Gerner’s name rarely made the newspapers. When it did, it was to reminisce about some of the great teams he had played on.

Gerner died on May 15, 1970, in Philadelphia. Surviving him was his wife, Daisy. The couple had no children. Gerner is buried in the Oakland Cemetery in Philadelphia.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on the following:

Barthel, Thomas. Baseball’s Peerless Semipros (Haworth, New Jersey: St. Johann Press, 2009).

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Simkus, Scott. Outsider Baseball (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014), 162-167.

Notes

1 “Eddie Gerner May Yet Be a Robin,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 26, 1928: 4A.

2 According to his Sporting News contract card digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/64833/rec/1; Baseball Reference lists him as 5-feet-8, 175 pounds. Gerner’s World War I draft registration card lists him as “Tall,” making the contract card height more likely.

3 Stan Baumgartner, “Sandlot Star Ready For 26th Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 27, 1941: 20.

4 Jack Ryder, “Two Men,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 17, 1917: 6; “Eddie Gerner Released,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, April 19, 1917: 15.

5 Waite Hoyt, “According to Hoyt,” Piqua (Ohio) Daily Call, April 3, 1942: 6.

6 “Stetson to Play Stars of Mack in Final Game,” Philadelphia Evening Ledger, October 5, 1917: 15.

7 “Mathewson to Take Reds Out,” Lima (Ohio) News, March 11, 1918: 5; “Foster Wants $6,000 to Pitch for the Reds,” Scranton Times-Tribune, April 12, 1918: 28; “New York Ship Has Close Call,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 9, 1918: 16.

8 “Little Bits of Baseball,” Pittsburgh Press, June 16, 1918: 27; Effie Welsh, “Welsh Rarebits,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, June 29, 1918: 9.

9 “Shipyard Ball Players Called by Draft Boards,” Scranton Tribune, August 20, 1918: 12.

10 “Gerner, Rath Sign,” Lima News, February 18, 1919: 10.

11 “Cincinnati Players Domestic in Plans for Coming Winter,” Sandusky (Ohio) Register, October 16, 1919: 9; “World’s Champions Scatter for Winter,” Sante Fe New Mexican, October 24, 1919: 2.

12 “Jack Ryder, “No Game at Raleigh,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 3, 1920: 6.

13 James B. Borland, Fifty Years in the Newspaper Game (Boston: Chapple Publishing, 1928), 191, 193-194.

14 “Reds Will Not Disturb Pitcher Eddie Gerner,” Franklin News-Herald, May 24, 1920: 3; Borland, 199.

15 “Oil City Was Leader in All Departments,” Franklin (Pennsylvania) News-Herald, October 1, 1930: 10. “Season Is Over and Players Are Leaving Franklin,” Franklin News-Herald, October 1, 1930: 3.

16 “Winter Baseball Gossip,” Franklin News-Herald, October 1, 1930: 3; Borland, 197.

17 “Farmers and Bushwicks to Clash Today,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 30, 1927: 13.

18 “Bushwicks and Farmers Resume Series Today,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 4, 1928: 13.

19 “Bushwicks of 1929 Are Rated Best White Semi Pro Team in History,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 3, 1929: 13.

20 “Bushwicks Had a Banner Season and Played Before Record Crowds, Night Baseball a Big Success,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 2, 1930: 12; “Bushwick Nine in Dexter Bow” Brooklyn Standard Union, March 21, 1931: 9.

Full Name

Edwin Frederick Gerner

Born

July 22, 1897 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

May 15, 1970 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.