Eddie Dyer

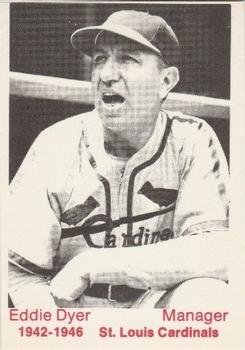

Eddie Dyer was one of the “Rickey men” who built baseball’s first farm system. He managed the St. Louis Cardinals to their last World Series championship of the Branch Rickey era.

Eddie Dyer was one of the “Rickey men” who built baseball’s first farm system. He managed the St. Louis Cardinals to their last World Series championship of the Branch Rickey era.

Edwin Hawley Dyer was born October 11, 1899, in Morgan City, Louisiana, the fourth of seven children of Joseph M. and Alice Natalie Dyer. Baseball encyclopedias give his birth date as 1900, but his son Eddie Jr. says he subtracted a year from his age when he entered professional ball. U.S. census and military draft records confirm this.

Joe Dyer owned a general store and a lumber yard and served as mayor of Morgan City. But he went broke in a recession before World War I and moved his family to Houston, where an oil boom was just beginning.

Eddie was an all-around sports star in high school and won an athletic scholarship to Rice Institute (now Rice University) in Houston. He was an All-Southwestern Conference football halfback, a track standout and a left-handed pitcher and outfielder in baseball. He pitched a no-hitter against Baylor’s Ted Lyons, later a Hall of Fame pitcher for the White Sox.

Dyer left school short of graduation in 1922 when Branch Rickey gave him a $2,500 bonus to sign with the Cardinals. The money paid off his father’s debts and put his youngest brother Sammy through one year of college.

According to St. Louis sportswriter J. Roy Stockton, Rickey paid the rookie his highest compliment: “Another Sisler, I’m telling you.” Rickey had coached George Sisler at the University of Michigan and signed him for the St. Louis Browns as a left-handed pitcher, but decided he was more valuable as a first baseman. In 1922 Sisler batted .420, his second time over .400.

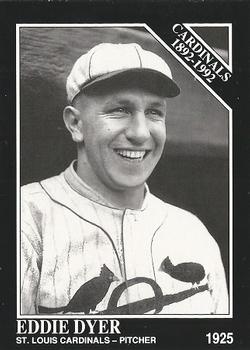

Like Sisler, young Dyer showed promise as a pitcher and a hitter. He made his debut with the Cardinals on the mound on July 8 and pitched twice in relief before he was farmed out to Syracuse, at the highest minor-league level. The next spring Rickey sent him to Houston, then to Wichita Falls, both in the Texas League, to play the outfield. When he didn’t hit, he became a full-time pitcher.

In 1924 he stuck with the Cardinals, but posted a 4.61 ERA and an 8-11 record, dividing his time between starting and relieving for the sixth-place club. The next year he lowered his ERA to 4.15, pitching primarily in relief. Rickey moved into the front office and the Cardinals’ star second baseman, Rogers Hornsby, became manager in 1925. He and Dyer did not get along. According to one account, Dyer told Hornsby, “I’ll never play on this club as long as you’re the manager.” That earned him a return ticket to Syracuse in 1926, while the Cardinals won their first World Championship.

In 1927 Dyer pitched once for St. Louis before he headed to Syracuse again. He won six games in a row, but on June 30 he hurt his arm in his first loss. That finished his pitching career.

Dyer had evidently impressed Branch Rickey with more than his playing talent. Rickey hired him to manage the Topeka Jayhawks in the Class C Western Association in 1928. Dyer had found a new career. He also joined a revolution.

Dyer had evidently impressed Branch Rickey with more than his playing talent. Rickey hired him to manage the Topeka Jayhawks in the Class C Western Association in 1928. Dyer had found a new career. He also joined a revolution.

“Starting the Cardinal farm system was no sudden stroke of genius,” Rickey once said. “It was a case of necessity being the mother of invention.” The Cardinals, one of two teams sharing a small market, could not afford to buy the best players from the minors. The price of young talent was rising; in 1922 the Chicago White Sox paid $100,000 to get third baseman Willie Kamm from the Pacific Coast League San Francisco Seals and in October 1924 the Philadelphia Athletics sent $100,600 to Baltimore for pitcher Lefty Grove. That was the way the baseball business worked before Rickey: minor league owners were independent operators who made their living by selling players to the highest bidder. To create his own talent pipeline, Rickey bought some teams and negotiated working agreements with others. St. Louis supplied its farm teams with some players and retained the right of first refusal when the prospects were ready to move up.

By 1928 the Cardinals owned or controlled eight minor-league teams, including Topeka. Dyer served as manager and played the outfield, batting .301. For the next five seasons he led low-level teams in the Cardinals’ system while batting above .320 every year. He continued managing after he quit playing in 1933. As the St. Louis chain grew, he compiled an itinerary that might have been the work of some sadistic travel agent: Scottdale, Pennsylvania; Springfield, Missouri; Greensboro, North Carolina; Elmira, New York; Huntington, West Virginia; Rochester, New York; Columbus, Georgia; Asheville, North Carolina. All except Rochester were in the low minors.

Dyer had married his Rice sweetheart, Geraldine Jennings, in 1928. Eddie Jr. was born the next year and daughter Geraldine followed five years later. His baseball job took him away from his family, but his son said, “He was damn glad to have it” during the Depression.

Dyer returned to Houston in the off-seasons to coach Rice’s freshman football team and completed his college degree in 1936. He also officiated in Southwestern Conference football games. He made friends among Houston’s leading businessmen, most notably Hugh Roy Cullen, “the king of the wildcatters,” who cut Dyer in for small investments in some of his profitable oil ventures.

Dyer became one of Rickey’s key lieutenants. Besides managing, he served as team president in Columbus, Georgia, and in Asheville, where Rickey sent his own son for an apprenticeship. Dyer spent 1938 as supervisor of the lower-level farm clubs in the southwest. He was one of a handful of men who conducted mass tryout camps for amateur players, following Rickey’s dictum: “Out of quantity comes quality.” Rickey devised a detailed system for evaluating as many as 100 players during a two-day camp and sent his most trusted scouts to watch raw teenagers show their stuff on pebbled diamonds across the country: Dyer, Charlie Barrett, Charles Kelchner, Joe Schultz and Joe Mathes.

After one of those tryouts, Rickey asked for a report on a young pitcher. Dyer judged that the boy was no prospect; it was his brother Sammy. He liked to tell about another player he rejected, a lanky North Carolina youth named Billy Graham. When they met again years later, Dyer told the celebrated preacher, “I remember you. You couldn’t hit a curve ball with an ironing board.”

By 1940 the Cardinals owned or controlled 32 teams and more than 600 players. (Today most major-league teams have five or six farm clubs and about 150 players.) St. Louis had a club in each of the 20 Class D leagues, the entry level of professional baseball. The Cards controlled more than one team in some leagues. Rickey’s farm system was a spectacular success on the field: from 1926 through 1949 St. Louis won nine National League pennants and finished second nine times, without buying a single player from another team. It was even more successful at the bank. Rickey’s biographer Murray Polner estimated the Cards sold more than $2 million worth of excess players to other big-league clubs. When the Depression cut down attendance, those deals often made the difference between profit and loss for owner Sam Breadon. They were pure profit for Rickey; his contract gave him 10 percent of the price for every player he sold. Thanks to the evaluation skills of Rickey and his staff, they gave up very few future stars.

In 1939 Dyer was named manager of his hometown team, the Texas League Houston Buffaloes, one of the Cardinals’ top farm clubs. Before the season he befriended a fatherless 17-year-old left-handed pitcher in his native Louisiana and gave the quiet boy a $3,500 bonus. Howard Pollet would become the ace of Dyer’s World Championship club and his lifelong friend, protégé and eventually his business partner. Dyer once called him “the type of man I’d like to have as a son or as a brother.”

Dyer’s ’39 Houston club won the first of three straight pennants. Pollet was farmed out, but the Buffs’ pitching staff was studded with future Cardinals: Harry Brecheen, Murry Dickson, Howie Krist, Ernie White and Ted Wilks. In 1940 Pollet joined the team and won his first 12 decisions. In ’41 Pollet posted a league-record 1.16 ERA and 20 wins before the Cardinals called him up.

Dyer was promoted to the Columbus (Ohio) Redbirds of the American Association in 1942, at the highest level of the minors. Columbus finished third, but won the post-season playoffs and beat International League champion Syracuse in the Junior World Series. It was Dyer’s ninth minor-league championship. The Sporting News named him minor-league manager of the year.

After St. Louis won the 1942 pennant and World Series, Rickey left to take over the Brooklyn Dodgers. Owner Breadon, a car dealer before he bought the Cardinals, resented paying Rickey his commission on player sales, although he had signed Rickey’s contract, and resented that Rickey, not he, was recognized as the genius behind the team’s success.

Breadon put Dyer in charge of the top farm clubs. As World War II claimed more and more players and forced many minor leagues to shut down, Dyer had fewer and fewer prospects to nurture. He quit in 1944 to join his brother Joe in the oil business. Around that time he founded the Eddie Dyer Insurance Agency, which later wrote property and casualty policies for Rice, the University of Houston and other local institutions. His brother Charlie helped run the business. Howard Pollet went to work there in the off-seasons and stayed for the rest of his life.

After the 1945 season Cardinal manager Billy Southworth, who had won three pennants in four years, moved to the Boston Braves for a three-year contract at $35,000 a year, far more than he was getting in St. Louis. Breadon said, “I wouldn’t stand in his way,” but he did not let Southworth go until Dyer agreed to manage the Cardinals.

When Breadon introduced his new manager, he explained, “I consider him the best judge of young players in the country, which I consider priceless at a time like this.” With World War II over, players were returning from military service. Nobody knew whether they would bring their baseball skills home with them. Because the Cardinals had the largest farm system, they had the most talent to sort out. Besides, 21 of the 56 players on the spring training roster had played for Dyer in the minors.

The war veterans included the entire starting outfield: 25-year-old Stan Musial, a star still rising, Enos Slaughter and team captain Terry Moore; plus 10 pitchers of prime age, headed by Pollet, Ernie White, Howie Krist, Murry Dickson and the 1942 rookie sensation Johnny Beazley. Surveying what one sportswriter called “an embarrassment of riches,” Breadon made two winter moves that threatened to torpedo the Cardinals’ chances. He sold both of his first basemen, Johnny Hopp and Ray Sanders, to Boston because he thought rookie Dick Sisler (George’s son) could handle the position. More important, he sent the league’s best catcher, Walker Cooper, to the Giants for $175,000. Cooper was a three-time All-Star and would be three more times, but he and his brother, pitcher Mort, had fought Breadon every winter over their salaries. Mort had been sold to the Braves the year before. Now Breadon claimed the catching Cooper had to go because he had clashed with Dyer in the minors. Dyer insisted he and Cooper could make peace, but he could not persuade Breadon to refuse New York’s money.

Even after those deals, The Sporting News reported the club looked “overwhelmingly strong for 1946.” But when spring training began, it was clear that several players had sacrificed their baseball careers for their country. Righthander Krist, who had gone to war after two straight seasons with ERAs under 3.00, had been injured while in service. Lefthander White, a 17-game winner in 1941, left his fastball on the frozen battlefield known as the Bulge. Hard-throwing righthander Johnny Grodzicki, the pride of the farm system, had been wounded by shrapnel and was trying to pitch wearing a brace on his damaged leg. None of them ever won another game in the majors. Beazley had ruined his arm when his commanding officer ordered him to pitch an exhibition game against the Cardinals; he was finished as an effective pitcher. Another top pitching prospect, Hank Nowak, had been killed in action.

It wasn’t just the pitching staff. Centerfielder Moore, nearly 34 years old, was noticeably slower and no longer able to play every day. Infielder Frank Crespi had broken his leg in a military training accident, then broke it again, reportedly while racing wheelchairs in an army hospital. He never played another big-league game.

Dyer took over a team that had won three straight pennants from 1942-1944 and finished a close second in 1945. The Cardinals were the consensus favorites for 1946. Dyer protested, “The Dodgers are deeper in more positions than we are.” But sportswriter Fred Lieb stated the conventional wisdom of the press box: “Dyer must win, or face the prospect of being termed a disappointment.”

The new manager was 46 years old, nearly six feet tall, with gray eyes, brown hair and prominent teeth. Those who knew him described him as friendly and outgoing — “a big personality,” Eddie Jr. said. In casual conversation he called players, sportswriters and his son “Pal.” Although he was a baseball lifer, his business experience gave him a broader perspective and more financial security than the average manager. Upon taking the job he said, “My theme song to my players for years has been: ‘Be mentally and physically fit to do your best, and we won’t worry about the results.’”

In his long minor league career Dyer had earned a reputation as a player’s manager and had formed close ties to several of the Cardinals. Teammates called Pollet “Eddie’s boy.” Utility infielder Joffre Cross, who had played for Dyer in Houston, later ran the insurance agency when the owner was away during baseball seasons. Pitcher George Munger worked there in some winters. Slaughter, renowned for his all-out hustle, said he learned that attitude when he played for Dyer at Columbus, Georgia, in Class B ball in 1936. The manager spotted him walking off the field between innings and said, “Son, if you’re tired I’ll get you some help.” Slaughter declared, “[F]rom 1936 until I finished my career in 1961 I never walked on a ball field. I left the dugout running and I hit the top step running coming back.” He described Dyer as “a big brother” to the players.

Most of the Cardinals had come up through the minors together, but there were two distinct cliques, shortstop Marty Marion remembered: the straight arrows — Marion named himself, Pollet, Harry Walker and Harry Brecheen (he might have added Musial and Red Schoendienst, who became Stan’s close friend and roommate) — and “the mean bunch…who drank a lot of beer and loved to play cards” — such as pitchers Beazley and Max Lanier and third baseman George Kurowski. Dyer banned card playing in the clubhouse because the games were getting too expensive for some of the losers. Captain Moore was the team’s enforcer; several teammates remembered his big hands whacking them on the back when he wanted to drive home a point.

After splitting their first two games in 1946, the Cardinals won six in a row. But, as Dyer had predicted, they were having trouble keeping up with Brooklyn.

The Dodgers weren’t the only ones stalking them. The four Pasquel brothers were courting major leaguers for their Mexican League, showing off suitcases packed with hundred-dollar bills. American baseball owners were alarmed. The new commissioner, Happy Chandler, decreed that anyone who defected to Mexico would be suspended for five years. The Pasquels signed several marginal players and two established ones: the Dodgers’ catcher Mickey Owen and the St. Louis Browns’ star shortstop, Vern Stephens. Stephens came home before the season opened, disgusted with the playing and living conditions in Mexico. (Among other things, he complained that when he turned on the faucet marked “C,” he got hot water — caliente in Spanish.) Owen wanted to return to the Dodgers, but Branch Rickey would not take him back.

The Pasquels targeted Cardinal players, perhaps because they knew of Breadon’s skinflint ways. On May 23 second baseman Lou Klein and pitchers Max Lanier and Fred Martin jumped the club and headed south.

Klein had been the Cardinals’ regular second baseman before he went into military service, but in 1946 he lost his job to young Red Schoendienst. Martin, a 30-year-old rookie, felt he was not getting a fair chance with so many other pitchers competing for innings. Lanier, however, was a key man. The 30-year-old lefthander had opened the season with six straight complete-game victories before he accepted a $15,000 bonus from the Pasquels and took off for Mexico with the cash stashed inside a radio. He later revealed that his arm was hurting and he feared for his future.

The most serious threat was the Pasquels’ determined pursuit of Stan Musial, who had already won the first of his seven batting titles and three most valuable player awards. Intermediaries approached Musial several times, raising their offer on every visit. In June Alfonso Pasquel met him at a St. Louis hotel and flashed five cashier’s checks totaling $50,000 — his signing bonus, nearly four times as much as Sam Breadon was paying the National League’s best player.

Musial always insisted he never seriously considered the offer, but he took it seriously enough to seek Dyer’s advice. The manager reminded Musial that he had signed a contract with the Cardinals: “Stan, signing a contract is just giving your word, that’s all. An honorable man doesn’t go back on his word. You wouldn’t want your children to think their father isn’t an honorable man, would you?”

Kurowski made the same argument to his teammates in a clubhouse meeting. His words carried weight because he had battled Breadon over his salary, holding out until the end of spring training. There were no more defections. Later that summer Breadon rewarded Musial, Slaughter and Moore with bonuses.

On the day the Mexican jumpers left the club, the Cardinals were tied for first place with Brooklyn. But the defections stunned Dyer and his team. He said, “I felt like our pennant chances had been shot out from under us.” Pollet came to his hotel room and volunteered “to carry a little extra load… Give me a day’s rest after I start a game and I can relieve if you need me. Then another day of rest and I can start again.” Dyer said later, “Howie wasn’t a robust fellow, but his heart was stout and I’ll never forget it.”

The Cardinals trailed the Dodgers by five games at the All-Star break, but the team was unsettled, especially the pitching staff. The 25-year-old Pollet had blossomed into an ace; he would lead the league with a 2.10 ERA and 21 victories. Brecheen, a left-handed screwball artist, recorded a 2.49 ERA, although his record was just 15-15 because of weak run support. But after subtracting the war casualties and the Mexican defectors, Dyer was scrambling to round out the staff. He used eleven different starters. Red Barrett, a 23-game winner against weak wartime competition in 1945, didn’t win his second game of 1946 until July 4. Right-handed reliever Murry Dickson, a veteran of the D-Day landing, was finally given a start on June 9 and finished with a 15-6 record and a 2.88 ERA. Dyer nicknamed him “Tom Edison Jr.” because he was notorious for experimenting with different pitches and different arm angles.

The sale of Walker Cooper had left the catching in the hands of rookie Joe Garagiola, young Del Rice and veteran journeyman Clyde Kluttz, all weak hitters. Rookie Sisler had flopped at first base, so Dyer moved Musial there.

Six Cardinals were chosen for the all-star team, including Pollet, Slaughter, Musial (as an outfielder) and three-fourths of the starting all-star infield: Schoendienst, Marion and Kurowski. Breadon’s castoffs, Walker Cooper of the Giants and Johnny Hopp of the Braves, also started the game. Hopp was leading the league in batting average.

After the All-Star break, St. Louis took four straight from Brooklyn and moved into first place on July 18. The Cardinals won 16 of 22 during their July home stand, but Dyer cautioned, “I expect it to be a fight right down to the finish.”

The fight went beyond the finish. St. Louis was one game ahead on September 24, but lost three of the last four. On the season’s final day either the Dodgers or the Cardinals could claim the pennant with a victory. Both lost.

Each team had won 96 games and lost 58. It was the first time a pennant race had ended in a tie. The National League had decided on a best-of-three playoff series. Brooklyn, winning the coin toss, chose to play the first game in St. Louis so they could have the home-field advantage for games two and three.

Some of the Dodgers later said that was a mistake. It meant they had to endure a 22-hour train ride from Brooklyn to St. Louis, with only one day off, then make the return trip after game one.

Dyer chose Pollet to start the first game on only two days’ rest. He had taken the young lefthander at his word and had ridden him hard and may have ruined his career. Pollet started 32 games and relieved in eight more, working a league-high 266 innings. By then he was hurting; he had strained muscles behind his shoulder when he relieved in an August game without a proper warm-up. Still, he went the distance to beat the Dodgers, 4-2. After the trek to Brooklyn, Dickson and his fishing buddy Brecheen put the weary Dodgers away to send St. Louis to the World Series for the fourth time in five years.

During the clubhouse celebration, Dyer made sure to point out that two teams built by Branch Rickey had outclassed the rest of the league. St. Louis had dominated the competition, scoring the most runs and allowing the fewest. Brooklyn was close behind in both categories. Musial led the league in runs, hits, doubles, triples, batting average and slugging average while ringing up an on-base-plus-slugging percentage of 1.021. He won the most valuable player award. Slaughter, the league’s RBI leader, finished third and Pollet fourth in the voting by baseball writers.

The American League champion Boston Red Sox were heavy favorites in the Series. Pollet started the opener in St. Louis and nursed a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning before he gave up the tying run with two out. According to one report, he was digging his fingernails into his palm to fight the pain in his shoulder, but Dyer left him on the mound for the tenth inning. It was the first of three managerial decisions that nearly doomed the Cardinals. Boston first baseman Rudy York touched Pollet for a game-winning home run in the tenth.

St. Louis evened the Series on Brecheen’s four-hit shutout. Moving to Boston, Dickson started the third game. In the first inning, another of Dyer’s moves backfired: with two men on, he ordered an intentional walk to Ted Williams. York followed with another home run. Boston won 4-0.

St. Louis rebounded with a 12-3 rout in the fourth game, punishing six Boston pitchers for 20 hits. It was Pollet’s turn in game five, but his aching shoulder had kept him awake all night after his first start and the team doctor had been working on him ever since. Dyer gambled that his boy was good for one more win. He wasn’t. Pollet threw only 10 pitches, allowing hits to three of the first four batters before he was relieved. The Red Sox won, 6-3.

In the sixth game Brecheen kept the Cardinals alive with another complete-game victory to set up one of the most famous and controversial deciding games in Series history. Dickson started and was protecting a 3-1 lead in the eighth inning. When he put the potential tying runs on base, Dyer called on Brecheen, who was pitching on only one day’s rest. The little lefty had awakened that morning with flu symptoms, though he kept that to himself. He let the tying runs score.

The bottom of the eighth produced the decisive events and the controversy. Slaughter scored the winning run all the way from first on Harry Walker’s base hit, beating Boston shortstop Johnny Pesky’s relay to the plate. Whether “Pesky held the ball” became an enduring debate — a song was even written about it. Slaughter’s version: Third base coach Mike Gonzalez had stopped him earlier in the Series when he believed he could have scored. Dyer told him to be aggressive and the manager would take any criticism. Before Walker’s hit, Slaughter said, Dyer had flashed him the steal sign. He ran on the pitch and was rounding second by the time the ball landed in the outfield; he never doubted that he could score.

Brecheen allowed the potential tying run to reach base in the ninth, but retired the side to make the Cardinals World Champions. His teammates carried the exhausted hero off the field. Brecheen was the first pitcher since 1920 to win three games in a World Series.

Overshadowing Brecheen’s performance, the big news of the Series was the failure of Boston’s Ted Williams. Dyer adopted the “Boudreau shift” supposedly originated by the Indians’ manager, positioning almost all his fielders on the right-field side of second base because Williams pulled nearly everything. Teddy Ballgame managed only five singles — one a bunt — in the seven games. Dyer said the shift robbed Williams of three more hits.

Back home in Houston, the mayor proclaimed “Eddie Dyer Day” and 700 people honored him at a testimonial dinner, including Governor-Elect Beauford Jester. Professional golfer Jimmy Demaret led the singing of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” The Sporting News named him manager of the year and one sportswriter voted for him for the Hall of Fame.

Dyer had been paid just $13,000 in his first year as manager, but Breadon added a $5,000 bonus for winning the pennant. The next year Dyer negotiated a bonus based on attendance. In the postwar baseball boom, St. Louis had drawn more than 1 million fans for the first time in 1946 and would do so every year while Dyer managed the club.

The Cardinals were again pre-season favorites for the pennant in 1947, but Dyer was not so confident. Terry Moore had undergone knee surgery and George Kurowski had surgery on his throwing arm during the off-season. Doctors had prescribed rest for Pollet’s shoulder; he was a question mark.

The defending champions played like chumps in the first weeks of the season. Even worse, they became the villains in the controversy that swirled around Branch Rickey’s “great experiment”: the arrival of Jackie Robinson, the twentieth century’s first black major leaguer.

With the club stumbling through a nine-game losing streak at the end of April, Breadon rushed to New York, where the Cardinals were playing the Giants. A man who was born poor and started his business career selling popcorn on a street corner, he saw his club losing games and feared losing attendance and losing money. He consulted the team leaders, Moore and Marion, about whether he should fire the manager. Moore recalled, “Marty Marion and I told Breadon that Dyer was not at fault, that he was a good manager and that the Cardinals would get going.” Their endorsement probably saved Dyer’s job.

The Cards stopped their slide by winning two out of three at Brooklyn. The day after that series ended, the other shoe dropped with a crash that was heard all over the country and resounded for decades. On May 9 New York Herald-Tribune sports editor Stanley Woodward reported what he claimed was the real reason for Breadon’s sudden trip to New York: “A National League players’ strike, instigated by some of the St. Louis Cardinals, against the presence in the league of Jackie Robinson, Negro first baseman, has been averted temporarily and perhaps permanently quashed.” Woodward wrote that the league president, Ford Frick, had spoken to the Cardinal players and bluntly warned them that they would be suspended — would be “outcasts” — if they went through with it, “and I don’t care if it wrecks the National League for five years.” The story alleged that players on other clubs had also been fomenting a strike, but Woodward named no players — and no sources.

The story ignited a firestorm. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch‘s editors woke up their reporter traveling with the Cardinals, Bob Broeg, and told him he had been scooped. Broeg roused team captain Moore at 2 a.m. Moore acknowledged there had been “some high-sounding strike talk that meant nothing,” as Broeg put it. Breadon called the story “ridiculous.” Dyer used the word “absurd.”

Their denials didn’t stick. Frick confirmed the gist of Woodward’s account, although he said he never talked to any players. (Woodward had quoted Frick’s “warning” at length, but the next day he backtracked and acknowledged he had made up the speech. The fake verbatim quotes still appear in many histories of the period.) In his memoir, Frick said Breadon had brought the rumor to him and he sent his stern message to the players through the Cardinal owner. He said Breadon reported back, “It was just a tempest in a teapot…letting off a little steam.”

Whether the strike threat was real or a newspaperman’s hype has been debated ever since. All Cardinal players who were asked about it insisted there had been no plot to strike, although a few acknowledged there had been talk. Many of them hung their denials on a technicality: they unanimously agreed there was no strike vote. (Woodward never said there was.)

The acid controversy lingers and permanently stains the reputations of some of the Cardinals. Slaughter said of Woodward, “That son-of-a-bitch kept me out of the Hall of Fame for twenty years.” Writer Roger Kahn, a Woodward disciple, got into a nasty argument with Broeg over the issue at a dinner nearly fifty years later — two old men snarling at each other while Musial, sitting between them, was kicking Broeg under the table to try to shut him up, according to Musial’s biographer James N. Giglio.

In decades of debate over the real or invented strike threat, manager Dyer is the dog that didn’t bark. No surviving record suggests that he knew of any revolt festering in his clubhouse. Given his close relationship with so many players, his silence is at least circumstantial evidence that no plot existed.

As for Dyer’s attitude toward Jackie Robinson, here is how Robinson described his first trip to St. Louis later that season: “I had serious misgivings about what was going to happen in St. Louis… Then a wonderful thing happened. When I walked out onto the field, Dyer got up from the bench and shook my hand. He welcomed me to St. Louis and the big leagues. I’ll never forget some of the things he said in that quiet moment. It lifted some of the load from my shoulders.”

When the Cardinals left Brooklyn in May, they were still in last place. On Breadon’s orders, Dyer banned drinking in the clubhouse and in public places. Musial, who had gone home suffering from appendicitis and tonsillitis, returned to go 0-for-22 and was batting .151 on May 18. St Louis didn’t raise its record to .500 until June 20. The Cardinals bounced back to finish second, five games behind the Dodgers.

Musial missed only five games, but said he felt weak all season; he underwent an appendectomy in the fall. Although his .902 on-base-plus-slugging percentage would be a career year for most players, it was more than 100 points below his 1946 performance. Pollet’s arm was still sore. “Every pitch hurt,” he said. His ERA more than doubled to 4.34 as his victories dropped from 21 to 9. While favoring his shoulder he developed bone chips in his elbow and had surgery after the season.

On November 25, 1947, the most successful era in St. Louis baseball history ended when Sam Breadon sold the club to a syndicate headed by Robert Hannegan, a Democratic Party leader, and Fred Saigh, a lawyer and real estate investor, for more than $4 million. Breadon had run the team since 1920. He was 70 years old and suffering from prostate cancer.

During spring training in 1948 a Sporting News headline asked, “Will Pollet and Musial Regain ’46 Form?” Musial answered yes with an exclamation point. He put up the best numbers of his career, leading the league in practically every batting category and falling just one home run short of the Triple Crown. (He lost one in a rainout.) He became the first National Leaguer to win three MVP awards. But Pollet’s arm did not recover. His ERA swelled to 4.54 and he was dropped from the starting rotation for nearly three weeks in July.

Brecheen picked up some of the pitching slack with a 20-7 record and league-best 2.24 ERA. But Murry Dickson finished 12-16 and gave up a major-league record 39 home runs. Moore and Kurowski were part-time players in their final full season. The Cardinals again finished second, this time 6 ½ games behind the Boston Braves, but the new owners signed Dyer to manage for two more years. The players applauded when Hannegan told them the news.

That winter the Cardinals sold Dickson to Pittsburgh for $125,000, over Dyer’s objections. Later accounts indicate that the owners needed the money to dissolve their partnership; Saigh bought out Hannegan a few days after the deal. It could have been worse; Pittsburgh owner Frank McKinney said Hannegan had offered to sell Musial for $250,000, but backed out.

By 1949 Branch Rickey had assembled most of the “Boys of Summer,” the Dodger lineup that would win five of the next eight National League pennants: Robinson, Campanella, Snider, Reese, Hodges and Furillo. Except for questionable pitching, he said it was the strongest team he had ever put on the field. The Cardinals had Musial, Slaughter and Schoendienst with a supporting cast that was getting older, not better. On paper they were no match for Brooklyn.

But they nearly pulled it off. In his Guide to Baseball Managers Bill James devised a system to predict a team’s performance based on its record over the three previous seasons. He calculated that Dyer’s 1949 team won 11 more games than expected.

Howie Pollet’s comeback was one big reason. After he gave up 11 runs in his first six innings, Dyer banished him to bullpen with a warning: “You’ve started your last game until you throw the damn ball hard.” Pollet returned to the rotation after more than two weeks in exile and reeled off a 20-9 record with a league-leading five shutouts and a 2.77 ERA, third-best in the league. The Sporting News named him the NL Pitcher of the Year. Musial drove in 123 runs and he and Slaughter each batted over .330.

The Cardinals were a game and a half in front on September 25, but lost four in a row. Pollet, who had run out of gas in September, got his 20th win on the last day of the season, but Brooklyn beat Philadelphia in 10 innings to take the pennant by a single game. The Cardinals finished with 96 wins.

Throughout Dyer’s tenure as manager, the Cardinals were an aging ball club, and their once-dominant farm system was no longer producing fresh arms and bats. Dyer, who had helped Rickey build that system, had taken over just in time to watch it crumble. After Red Schoendienst joined the club in 1945, St. Louis did not develop another outstanding player until pitchers Harvey Haddix and Vinegar Bend Mizell arrived in 1952.

The symbol of their frustration was the never-ending search for a first baseman. Rickey sold Hall of Famer Johnny Mize in 1941 and Breadon dumped the wartime incumbents, Johnny Hopp and Ray Sanders, after 1945. The touted rookie Dick Sisler proved to be no better than a journeyman, so Musial played first for most of two seasons. Next came Nippy Jones, who had no power and a bad back. Then Rocky Nelson rocketed through the minors batting over .300. He hit .249 in the majors. In 1949 Saigh boasted about the huge young slugger Steve Bilko: “He’s a right-handed Lou Gehrig. Don’t you agree, Eddie, that he’s the spitting image of Gehrig?” Dyer replied, “Only across the seat of his pants.” (One of Gehrig’s nicknames was “Biscuit Pants” for his massive backside.) Bilko’s power seduced several big-league teams, but his strikeouts spoiled every romance.

Time caught up with the remnants of the Rickey dynasty in 1950. St. Louis slid to fifth place with a 78-75 record. Several front-line players got hurt and no adequate replacements were available. After the season Dyer choked up as he announced his resignation. Saigh later said “public pressure” forced him to replace the manager.

There was speculation that Dyer would take a front-office job with the Cardinals, but after 28 years in the organization he returned to his substantial business interests in Houston. He owned the insurance agency, oil and real estate holdings, and was vice president of a Canada Dry soft-drink franchise. He made Howard Pollet and Joffre Cross partners in the insurance business.

He kept his hand in baseball as an instructor at the Lone Star Baseball Camp for boys during several summers and as chairman of an annual father-son dinner at the Houston ballpark. His wife Geraldine proudly said she was the godmother of 22 children of former big leaguers.

Dyer suffered a stroke in January 1963 and died at home on April 20, 1964, at age 64. His wife, son and daughter survived. Eighty-two-year-old Branch Rickey was among the mourners at his funeral at St. Anne’s Catholic Church.

Six months after his death, one of his former players, Johnny Keane, managed the Cardinals to a World Series victory over the Yankees. It was St. Louis’s first championship since Dyer’s club won in 1946.

Sources

Most information about Dyer’s career comes from The Sporting News, 1922-1964, and www.retrosheet.org.

Red Barber, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball. Doubleday and Company, 1982.

Warren Corbett, “Murry Dickson,” http://bioproj.sabr.org, 2004.

Warren Corbett, “Howie Pollet,” http://bioproj.sabr.org, 2005.

Arthur Daley, “Tall in the Saddle,” The New York Times, April 24, 1964.

Edwin H. Dyer Jr., interview, April 15, 2005.

Ford C. Frick, Games, Asterisks and People. Crown Publishers Inc., 1973.

James N. Giglio, Musial: From Stash to Stan the Man. University of Missouri Press, 2001.

Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis. Spike/Avon Books, 2000.

Donald Honig, “Enos Slaughter,” Baseball Between the Lines in A Donald Honig Reader. Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1976.

Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers. Scribner, 1997.

Roger Kahn, Memories of Summer. Hyperion, 1997.

Richard Malatzky of the SABR Biographical Committee provided the Selective Service record of Dyer’s birth date in an e-mail message, April 17, 2005.

William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era. The University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

Stan Musial, “The Man’s” Own Story, as told to Bob Broeg. Doubleday and Company, 1964.

Murray Polner, Branch Rickey. Signet, 1982.

Branch Rickey with Robert Riger, The American Diamond. Simon & Schuster, 1965.

Neil J. Sullivan, The Minors. St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Frederick Turner, When The Boys Came Back. Henry Holt and Company, 1996.

Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment. Oxford University Press, 1983.

U.S. Census, St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, 1910.

U.S. Census, Harris County, Texas, 1920

Stanley Woodward, New York Herald-Tribune, May 9 and 10, 1947.

(no byline), “Breadon Gives His Side,” Associated Press, April 8, 1947, in the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Full Name

Edwin Hawley Dyer

Born

October 11, 1899 at Morgan City, LA (USA)

Died

April 20, 1964 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.