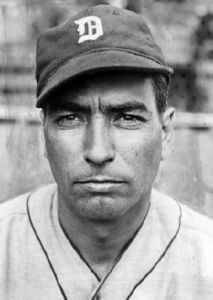

Elon Hogsett

His nickname of “Chief” fueled the belief that Elon Hogsett was part Indian. The press and fans just ran with it. Yet this lefty pitcher actually had precious little Native American blood. In a June 1982 interview with author Richard Bak, he said, “Am I really Indian? Well, I’m one-thirty-second Cherokee on my mother’s side. Maybe more, but whoever figured that out quit checking. Probably afraid of what they might find.” Still, the swarthy Kansan looked the part, and the well-worn moniker “just kind of stuck.”1

His nickname of “Chief” fueled the belief that Elon Hogsett was part Indian. The press and fans just ran with it. Yet this lefty pitcher actually had precious little Native American blood. In a June 1982 interview with author Richard Bak, he said, “Am I really Indian? Well, I’m one-thirty-second Cherokee on my mother’s side. Maybe more, but whoever figured that out quit checking. Probably afraid of what they might find.” Still, the swarthy Kansan looked the part, and the well-worn moniker “just kind of stuck.”1

Hogsett’s big-league career as one of the earlier relief specialists in the majors covered 11 seasons (1929-38; 1944). He helped the Detroit Tigers to back-to-back pennants in 1934 and 1935, winning a World Series ring in ’35. His pitching motion was Hogsett’s most distinctive trait. Submariners are rare birds, rarer still if they are southpaws.

Elon Chester Hogsett was born on a farm just outside of Brownell, Kansas, on November 2, 1903. His parents were Casper Wilson (C.W.) Hogsett —whose grandfather spelled the surname Hogshead —and Jessie Nora Ball. C.W. and Jessie, who married in December 1892, had three children before Elon: a boy named Don, a daughter named Dana, and then another son, named Aubrey. However, the marriage dissolved sometime after 1905. C.W. remarried and moved to Illinois.

Jessie also got married again, to Harry Jerald Cranston, in December 1907. Cranston, a widower, had lost his wife in 1904. The Hogsett children had five stepsisters and two stepbrothers; a half-brother named Harry and two half-sisters named Mildred and Jessie would join them.

Young Elon hated the farm and his carousing stepfather. He left home when he was 14 and never came back, though he pitched for the Brownell high-school team and various town ballclubs. One legacy of the farm, though, was Hogsett’s underhand motion, which came from skipping stones in boredom.

In 1925, the 21-year-old turned pro with a team in Independence, Kansas, but was cut. He then joined the Cushing (Oklahoma) Refiners in the Class D Southwestern League. As Hogsett recalled, the Tigers picked up his contract that year, though farm systems as such had not really taken hold across the majors. Hogsett was 16-15; his ERA is not available.

Something else was perhaps more notable, though —“That’s where they first started calling me Chief,” Hogsett told Richard Bak. “I roomed with a full-blooded Kiowa Indian.”2 However, Hogsett also told Wichita Eagle reporter Mike Berry in 1989 that a traveling salesman dubbed him “Chief” while he worked as a bellhop for his sister in a hotel, since the man thought Hogsett looked like an Indian.3

In 1926 Hogsett played at Class D (with the Marshall Snappers, a.k.a. Indians, of the East Texas League) and Class A (Fort Worth of the Texas League). His total record was 6-14; again, his ERA is not available, neither is the breakdown of stats by level. The book Baseball in Fort Worth implies that Chief was in the Panthers’ rotation. However, line scores show only that he was there in March and April for exhibition games, while he was a regular starter for Marshall in the summer.

One of the first substantial news stories on Hogsett that can be found online (from the Decatur Review, May 12, 1927) indicates that his regular-season record came with the Snappers:

“Elon ‘Chief’ Hogsett, a pitcher who didn’t win but six games as compared to 14 losses last year in a Class D loop … looked and acted like a hurler that should possess a much better record than the books gave him credit for last season.”4

That story was written after Hogsett had joined the Decatur Commodores of the Three-I League (Class B). Already newspapers were taking his heritage on faith, labeling him “the big Indian,” though 10 days earlier the Decatur Herald rightly remarked that he had just “a trace of Indian blood in his veins.”5 Yet despite a 5-1 record for the “Commies,” he was sent down to the Wheeling Stogies of the Middle Atlantic League (Class C) in early June. The Decatur Review said on June 8 that “he couldn’t get going at home. Three times he started at Fans’ Field, and three times [manager Harold] Irelan had to remove him before the third inning.” Decatur’s star pitcher that year was Carl Hubbell.

Hogsett’s overall numbers in 1927 were 9-10, 2.69. He climbed back to the Three-I League in 1928, but with the Evansville Hubs rather than Decatur. Though he finished below .500 at 14-15 (for a 62-68 team), his ERA was a respectable 3.29. Charles “Punch” Knoll, manager of Fort Wayne in the Central League (also Class B), brought Hogsett in as a playoff reinforcement at the end of the season. Previously, on July 27, the pitcher married his high-school sweetheart, Mabel Edith Wilson. They remained wed for 52 years.

In December 1928 Hogsett was sold to the Montreal Royals of the International League. The next year he became an IL All-Star, leading the league in wins with 22 against 13 losses (3.03 ERA). Hogsett also became an honorary member of the Iroquois Nation in 1929. Over 50 years later, he recalled to Richard Bak, “Those Indians around Montreal were big baseball fans. Before I left, they had a ceremony at home plate [and] gave me the name ‘Ranantasse.’ It means ‘strong arm.’”6

On August 17 St. Louis Cardinals manager Bill McKechnie observed to the Syracuse Herald, “That Indian pitcher, Hogsett, of Montreal, seems to me to be the best pitching prospect of any in the league.”7 Shortly thereafter, the Tigers acquired him (reportedly for $40,000 cash and unknown players), with the agreement that he would report at the end of the IL season. There were “hints of ‘something funny’ in the deal,” reported the Toronto Star —enough to prompt Kenesaw Mountain Landis, commissioner of baseball, to go to Montreal in person in early September.8 It would appear that Judge Landis satisfied himself, though, for nothing else came of that story.

Hogsett made his major-league debut on September 18; he lost a 1-0 duel to Washington’s Lloyd Brown. In the ninth inning, Sam West dragged a bunt past Hogsett and later scored on Joe Judge’s single. Four days later, though, the Chief rebounded for his first win. Backed up by four double plays, he shut out the St. Louis Browns, 5-0.

Over the next three years, Tigers manager Bucky Harris used Hogsett as a swingman. The submariner started 44 times in 102 appearances, with a total record of 23-26. He went back to Toronto for part of the 1931 season owing to a sore arm. Chief’s record with the Maple Leafs from mid-May through early July was an uninspiring 2-6, 4.25. Still, the Tigers needed him anyway. The Sporting News reported on July 9 that Waite Hoyt had been released because he’d let himself get out of shape, while Charlie Sullivan went home to be with his seriously ill father. That article also observed, “Hogsett seems to have taken on considerable weight … and this may prove beneficial. Last summer he suffered from a stomach ailment and was considerably below his normal poundage.”9

The 1932 season was probably Hogsett’s best in the big leagues: 11-9, 3.54 in a career-high 47 games. He started 15 times that year, but then his role changed almost exclusively to the bullpen. In March 1933 The Sporting News stated that “Hogsett was the best relief pitcher Detroit had last summer, but Harris feels that with [Firpo] Marberry around, he does not need the Indian southpaw for that sort of work.”10 As it developed, though, Hogsett started only twice in ’33.

In July 1933 Clifford Bloodgood in Baseball magazine described the hurler’s style. “Hogsett is primarily an underhand pitcher, but of late he has been slipping over a side arm delivery. He has a good sinker and a mystifying curve which makes him feared and respected by every left-hand batter in the American League. It breaks up and away and is called in the parlance of the game a ‘butterfly.’ Batters also look very feeble at times against his number two bender. This breaks down.”11 Hogsett also told author Brent Kelley, who interviewed him for his 1995 book In the Shadow of the Babe, that his “curve” was actually a slider.

The Bloodgood article was also notable for its stereotyped tone, as author Charles Alexander wrote in a 2002 essay. Entitled “Elon Hogsett, the Cherokee Pitcher,” Bloodgood’s piece “assured readers that the Detroit lefthander did not possess a quiver and bow, was not wrapped in a blanket, and was not ‘leaping up and down brandishing a tomahawk fiercely threatening butchery.’” The fans at Detroit’s Navin Field always greeted Hogsett with war whoops when he appeared, but considering that Braves fans still do the “tomahawk chop” today, not that much has changed.

With the arrival of catcher-manager Mickey Cochrane, Hogsett pitched solely in relief for the pennant-winning Tigers of 1934 and ’35. The way Cochrane used him would become much more common decades later. In his 66 outings over those two seasons, Hogsett pitched 147 innings —roughly 2⅓ per appearance. He said to Richard Bak, “I’d come in and pitch to those left-handers. … (T)he Yankees had five of them in a row in those days —Ruth, Gehrig, Lazzeri, Dickey, and Combs. How’d I pitch Gehrig? Not very good. … He hit me a hell of a lot better than the Babe. Gehrig could cut your legs off, he hit the ball so hard. But what I remember about Gehrig is how he used to murder cigarettes.”

Hogsett pitched in three games in the 1934 World Series, which the Cardinals won. He allowed just one run in 7⅓ innings, never appearing while the Tigers led. He faced four batters in the third inning of the 11-0 final game and retired none, as St. Louis scored seven and broke the game open.

Health was also a reason why Hogsett pitched so infrequently in 1934 (26 games). The Sporting News reported on November 22 that “the nonchalant lefthander … has just finished having his teeth overhauled in the hope of bettering his physical condition. When the rest of the Tigers departed shortly after the World’s Series, Hogsett stayed here for a series of sessions with his dentist. The job has now been completed and Elon believes one of the troubles that handicapped him last season has been removed.”12

Indeed, Chief was busier and more effective in 1935. In the World Series he added another scoreless inning in Game Three, and the Tigers went on to top the Cubs. The family highlight for the Hogsetts that year, though, came when their daughter, Virginia, was born. In a sign of the team’s camaraderie, the little girl was named for the wife of backup catcher Ray Hayworth. Hogsett would later tell her that Babe Ruth, well known for his love of children, bounced her on his knee.

On April 30, 1936, Detroit dealt Hogsett to the St. Louis Browns for first baseman Jack Burns. With a frightening team ERA of 6.24 that year, the Browns needed starters badly. Hogsett led the club in starts (29) and wins (a career-high 13, with 15 losses and a 5.52 ERA). When Joe DiMaggio went 3-for-6 in his big-league debut on May 3, he tripled off Hogsett. “The guy that murdered me was Joe DiMaggio,” Hogsett, grinning broadly, told Mike Berry five decades later.

In 1937 he endured a miserable year for the impoverished last-place Brownies. His mark of 6-19, 6.29 fueled a lifetime ERA (5.02) that was the century’s highest for pitchers who hurled at least 1,000 innings (1,222 in his case). This spurred authors James and Alan Kaufman to write a letter in 1990 as they compiled their sharp-edged yet basically good-natured book The Worst Baseball Pitchers of All Time. “The Chief, known in his playing days as being extremely stingy with the spoken word, responded … by writing this short message: ‘I never was a star —but I played with and against a lot of them. I am not in the Hall of Fame either but being a pitcher, perhaps I helped get some of them there.’”13

On December 1, 1937, St. Louis traded Hogsett to the Senators for Ed Linke. He went back to a swingman role in Washington for the 1938 season (5-6, 6.03, nine starts in 31 games). That December 7 the Washington Post reported, “Clark Griffith’s first move to reconstruct his club for 1939 took the form yesterday of the outright sale of Pitcher Elon Hogsett, 34-year-old southpaw, to the Minneapolis team of the American Association.” Terms of the sale were not given.

Hogsett was a solid starter with the Millers for the next three seasons. He posted won-lost records of 16-9, 16-11, and 18-9 with an ERA just over 4.00 each year. On October 3, 1939, the Philadelphia Athletics selected him in the annual major-league (Rule 5) draft. When February 1940 came around, the Christian Science Monitor reported that according to A’s owner/manager Connie Mack, Hogsett had returned his contract unsigned. Eleven days later, on February 16, the same paper said they had agreed to terms. However, Mr. Mack released the pitcher in April. It was an “Expensive Experiment,” said the Monitor on April 16. “It seems that … the Athletics paid $1,800 for the privilege of conditioning Hogsett for the Millers.”

In November 1940 the Hogsetts welcomed their second child, a boy called Stanley Gordon —Mickey Cochrane’s given names in reverse. The following season featured a near no-hitter on July 2. At home against Kansas City, Chief retired the first 16 batters. Though he got wild after that, walking five, he only lost his no-hit bid when Buster Mills singled with two out in the ninth. Two weeks later Hogsett started and took the loss for Minneapolis against the American Association’s All-Stars.

The Indianapolis Indians purchased Hogsett on March 13, 1942, for an undisclosed sum of cash from Minneapolis. He went 11-10, 3.50 for Indy, but in 1943, he pitched little and poorly. The Indians released him in early August, and he rejoined Minneapolis. His combined record for the year was 1-4, 6.98.

Despite his ineffective 1943 season, the wartime shortage of bodies got Hogsett a final run with the Tigers in 1944. The 40-year-old was described as “one of the best conditioned pitchers in the Detroit camp.”14 Indeed, he opened the season with the big club. On April 20, after Hal Newhouser and Joe Orrell got shelled, Hogsett blanked the Browns on three hits in the last 5⅓ innings. However, he appeared only twice more for the Tigers, making his last major-league appearance on June 3, 1944. Detroit released him the next day; he then went back to the Millers once more, going 5-7 with an inflated 6.83 ERA in 87 innings across 31 games.

Elon Hogsett then retired from baseball. In 1989 he commented to Mike Berry, “I’m not proud of my record [63-87, 5.02] by a damn sight.”15 But in fairness to him, ERAs in the 1930s were inflated. The league average during his career was 4.73, and so he really wasn’t too much worse than the norm overall. In today’s game, he probably would have been used only as a specialist —but as a starter he suffered by having to face right-handed batters on a steady basis. Hogsett allowed 11.1 hits and 3.7 walks per nine innings on average. His submarine sinker did not yield many home runs —just 85, or one every 14 innings.

In addition, Hogsett was a rather strong batter for a pitcher, posting a lifetime average of .226 with 6 home runs in 403 at-bats. Two of those homers (plus a single) came on August 31, 1932, off Philadelphia’s Tony Freitas at Shibe Park. Hogsett’s seventh-inning blow won the game, snapping a 10-game win streak for Freitas.

After leaving baseball, Hogsett spent five years selling sporting goods and, later, wholesale liquor along the East Coast. In 1949 he and Mabel returned to Kansas, where he worked the next 24 years as a liquor salesman. As Hogsett told Mike Berry, he “logged a thousand miles a week covering 23 northwest Kansas counties.” Most of his customers never knew they were dealing with an ex-major leaguer. “My boss said, ‘Chief, why don’t you blow your own whistle?’” Hogsett said. “I told him if I can’t make it on my own, I don’t want it.”16

Once Hogsett retired, he lived out the rest of a remarkably long life in the town of Hays, Kansas. His longevity and salty storytelling made him a favorite source for sportswriters and oral historians. Hogsett’s chapter in Richard Bak’s Cobb Would Have Caught It is one of the book’s most entertaining, spiced with reminiscences of his teammates and opponents, the old school of playing hard on and off the field, losing money in assorted dodgy investments, and more.

Mabel Wilson Hogsett passed away on August 7, 1980, after her second stroke. Widower Elon Hogsett survived her for over two decades. He lived by himself in his small house, regularly enjoying baseball on TV. He made it back to Detroit as an honored guest on July 12, 1983, as the Tigers retired uniform numbers 2 and 5 for his Hall of Fame teammates, Charlie Gehringer and Hank Greenberg. The taciturn Gehringer and Hogsett were road roommates for five years. The tale is often told of how days would go by without either feeling the need to speak (“Pass the salt” —“You could have pointed”). Their friendship lasted a lifetime, though, as the old second baseman stayed in touch until his final illness in 1993. The same was true of the last surviving member of the 1935 Tigers, fellow Kansan and submariner Elden Auker.

Although for many years he was self-sufficient, Hogsett eventually had to move to a rest home in Hays. He died on July 17, 2001; dementia is listed on his death certificate. Hogsett was laid to rest in Brownell Cemetery (also known as Vansburg Cemetery, from the original settlement’s name), just down the road from the farm where he was born almost a century before.

Thanks to Virginia and Stanley Hogsett for their assistance.

Sources

Bak, Richard, Cobb Would Have Caught It: The Golden Age of Baseball in Detroit. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991).

Berry, Mike, “Playing Days Long Past, Kansan Still Having a Ball,” Wichita Eagle, October 2, 1989.

Kaufman, James C., and Alan S. Kaufman, The Worst Baseball Pitchers of All Time: Bad Luck, Bad Arms, Bad Teams, and Just Plain Bad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1993).

Auker, Elden, with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001).

Alexander, Charles C., “Baseball Lives in the Depression Era,” Chapter 1 of The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture 2002, William M. Simons, editor (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company).

Kelley, Brent, In the Shadow of the Babe (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company 1995).

paperofrecord.com (The Sporting News).

ancestry.com (information on Hogsett’s family and step-family).

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Notes

1 Richard Bak.

2 Richard Bak.

3 Mike Berry, “Playing Days Long Past, Kansan Having a Ball,” Wichita Star, October 2, 1989, 1C.

4 H.V. Millard, “Bait for Bugs,” Decatur Review, May 12, 1927, 15.

5 “Chief Hogsett Goes Route and Holds Huts to 7 Hits,” Decatur Herald, May 2, 1927, 12.

6 Richard Bak.

7 John R. Foster, “M’Kechnie Sees Decline in Baseball Playing Ability,” Syracuse Herald, August 17, 1929.

8 “Landis to Probe Elon Hogsett Case,” Decatur Review, September 1, 1929, 11. This brief account quoted the story in the Toronto Star.

9 Sam Greene, “Alexander Spark Plug as Tigers Shake Slump,” The Sporting News, July 9, 1931, 3.

10 Sam Greene, “Harris Plans to Use a Rookie in Cleanup,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1933, 8.

11 Clifford Bloodgood, “Elon Hogsett, The Cherokee Pitcher,” Baseball Magazine, July 1933.

12 Sam Greene, “Detroit Faces Task Putting Over Deals,” The Sporting News, November 22, 1934, 5.

13 James C. and Alan S. Kaufman.

14 “Training Camp Briefs,” United Press, March 30, 1944.

15 Berry, “Playing Days Long Past, Kansan Having a Ball.”

16 Berry, “Playing Days Long Past, Kansan Having a Ball.”

Full Name

Elon Chester Hogsett

Born

November 2, 1903 at Brownell, KS (USA)

Died

July 17, 2001 at Hays, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.