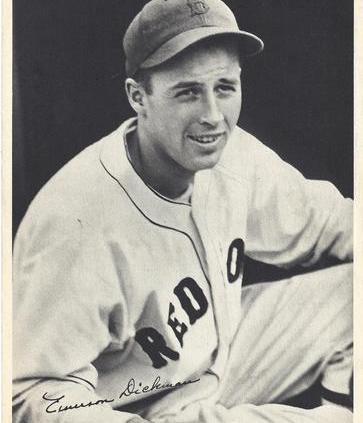

Emerson Dickman

A prewar pitcher, Emerson Dickman was a fastballing, curveballing right-handed reliever for the Red Sox.

A prewar pitcher, Emerson Dickman was a fastballing, curveballing right-handed reliever for the Red Sox.

Born George Emerson Dickman on November 12, 1914 to George Emerson Dickman Sr. and Mary (Hagen) Dickman, Emerson came from Irish and German stock. A younger sister, Joan, completed the family. The elder George was connected with Fox Films, selling its movies to theaters. Fred Lieb, who profiled Dickman in The Sporting News, wrote that he started pitching in grammar school and continued at Nichols Prep School in his hometown of Buffalo, New York. He also took up football and hockey there. Lieb also compared Emerson’s looks to those of Robert Taylor, a Hollywood leading man of the day. This earned him some ribbing from the bench jockeys of the American League. In addition to team sports, Dickman was also a squash player.

A childhood friend, Jack Cook, who captained the baseball team at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, recruited Dickman for the team. There, Emerson was a two-sport star and belonged to the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity. During his sophomore year, he won eight games and struck out 73 as the squad won the Southern Conference championship. In the summer, Dickman pitched for the Buffalo Blue Coals, a semipro outfit that went to the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita.

The New York Yankees almost signed Dickman after his junior year in 1936. Ivory hunter Paul Krichell was schmoozing with Dickman’s father in a Buffalo hotel when he received a call from Ed Barrow to drop everything, travel to Maryland, and go after Charlie “King Kong” Keller.

The 6-foot-2, 175-pound Dickman signed instead with the Boston Red Sox after his junior season. Supposedly contenders, the 1936 Red Sox had a fractious clubhouse that proved to be too big a barrier. They were called the “Millionaires” after owner Tom Yawkey’s free spending ways. They did their share of drinking. The pitching staff didn’t get along with manager Joe Cronin, who was more offensive-minded than defensive-minded. The team craved young pitching, signing Chicago schoolboy Frank Dasso, Dartmouth’s Ted Olson, and Dickman. Dickman’s career, such as it was, was the best of the three.

Emery, as the Boston newspapers called him, was supposed to meet the team in Buffalo as their train made its way west but didn’t join them until June 16, when they started a western trip in Chicago. Dickman warmed up that first day with polymath-catcher Moe Berg. “The finest prospect I’ve seen in a long time,” enthused Berg, “He looks fine. I predict something for that fellow.” It was the first time Dickman had picked up the ball in a month.

Lefty Grove and Wes Ferrell helped coach Herb Pennock work with the younger pitchers that year. After Dickman threw batting practice, Ferrell hustled him to the outfield, telling him that he needed to shag flies to get in shape. Ferrell started that night but failed to run out a grounder to shortstop that the Chicago White Sox’ Luke Appling airmailed wide of the bag at first. “Don’t take that as an example, Dick,” some Sox said to the young hurler.

Dickman stuck with the team for the road trip. Farm director Billy Evans felt it would be a good experience for him to get into a game before being assigned to a minor-league team. Dickman appeared in his first game on June 27. Wes Ferrell started against his old team in Cleveland, but the Tribe beat the Red Sox, 14-5. Neither Jack Wilson nor Rube Walberg did the job in relief, and Cronin gave the ball to Dickman to pitch the eighth. He struck out two, walked one, gave up two hits, threw a wild pitch, and gave up two runs, one earned. It proved to be his only appearance until 1938. The next day, there was a small Buffalo contingent at the game and they presented Dickman and Cleveland’s Frank Pytlak (another native of their city) with gifts.

As Evans had intended, Dickman spent some time traveling with the big club and working with pitching coach Pennock before being sent to Rocky Mount, North Carolina, of the Class B Piedmont League. At Rocky Mount, the tall, wiry right-hander pitched 63 innings in nine games, going 5-0 with a 1.86 ERA. In 1937, he was assigned to Little Rock of the Class A Southern Association. He went 16-8 with a 4.04 ERA for Doc Prothro’s Travelers and helped them to the Southern Association championship before wrenching his back.

Dickman spent the next 3½ years with Boston, mainly in the bullpen. In 1938, he was able to crack the rotation in July after some relief success. He appeared in 32 games, starting 11, and posted a 5-5 record. The lifetime .145 batter also hit his only career home run, off Chubby Dean in Philadelphia on July 2. He finished the season with a 5.28 ERA. He threw his one and only career shutout on July 25, a 4-0 win over the Indians in the first game of a Fenway doubleheader.

Dickman’s best year was 1939, when he appeared in 48 games, all but one in relief, and had five saves and an 8-3 record. Though saves were not officially tracked in those days, his five would have been good enough to rank sixth in the American League. (The Yankees’ Johnny Murphy led with 19 and Dickman’s bullpen mate, veteran Joe Heving, had seven.) Dickman had an ERA of 4.43; which was pretty good keeping in mind that Fenway was his home park. He also had career highs in wins, IP, appearances, strikeouts, and a career-low ERA

Highlights of Emerson’s 1939 season included a win against the Yankees on July 7. He entered the game in the sixth with the game 3-3 and runners on second and third. Dickman intentionally walked King Kong Keller to load the bases, then struck out the next two batters to retire the side. This started a five-game sweep of the Yanks that brought the Bosox within striking distance of the New Yorkers (6 ½ games.) Dickman garnered another win with another long relief stint in the series.

He had a win against Cleveland on July 15. After the Tribe knocked Fritz Ostermueller out of the box in the fifth, Dickman held them scoreless the rest of the way. This extended the Bosox winning streak to eight games, and they eventually extended it to ten. Dickman also had a game in St. Louis against the Browns where he replaced Jack Wade in the second and went 7 2/3 innings to get the win. They don’t use relievers like that 70 years later!

Dickman started 1940 in the rotation, but lasted only a month before returning to bullpen duty. He appeared in 35 games (8-6, with three saves). That year, his ERA crept over 6.00. He saw little duty in 1941, getting into only nine games (three starts), and posting a 1-1 record. His final major-league appearance was on June 26, 1941. Emerson gave up a triple to Roy Weatherly – the two had debuted in the very same game in 1936 – and let him score on a wild pitch in the last inning of an 11-8 Red Sox loss to Cleveland. Dickman’s major-league career had lasted one day less than five years. After that game he was assigned to Louisville. Nevertheless, 1941 was not a bad year for him. He met his future wife, a cover girl named Connie Joannes. He was in Valdosta, Georgia, en route to Sarasota for spring training with a friend from home, Bill Farnsworth. Bill knew a woman who was there with Connie. They were either shooting a Lucky Strike ad or on a nationwide tour for Coty perfume. Bill set up Em and Connie. Dickman married the 19-year-old New Jerseyite in the fall. (Incidentally, Farnsworth went on to marry Alan Ladd’s ex-wife.)

Dickman might have made it back to the majors. His stats weren’t great, but he was hardly over the hill at 27 when the attacking Japanese navy sounded the tocsin of war at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

On January 19, 1942, just six weeks after the attack, Dickman enlisted in the Naval Reserve. Dickman started his naval career as a storekeeper third class. He spent most of the war at King’s Point, New York, home of the United States Merchant Marine Academy but was recruited by Lieutenant Commander Jimmy Powers, erstwhile sports editor of the New York Daily News to serve along with some other athletes in the Morale and Athletics Department which Powers commanded. Dickman earned his commission as an ensign and rose to the rank of lieutenant during the war.

Dickman was a physical training instructor, keeping cadets fit, he said, with “Gene Tunney tactics.” He also coached baseball at the academy. It was a nine to five life. He’d leave their apartment in nearby Great Neck and head to the academy. Connie would go into New York City for modeling assignments. They couple had two sons (Emerson and Robert) during the war. Before the war ended, he was transferred to Hawaii for a period of time.

Dickman told a reporter from The Sporting News that he wanted to get into advertising after the war. In a feature article on his wife, he told the writer that he wanted to open a restaurant or a sporting goods store. What he didn’t do was return to professional baseball, but he did play semipro ball in the New York City area.

Dickman coached baseball at Princeton from 1949 to 1951. The Tigers won the Eastern Intercontinental Baseball League all three years. They made their only appearance in the College World Series in 1951 before losing to USC and Tennessee. Dave Sisler was among Dickman’s players and thought that coaching was more of an avocation than a job for the former pitcher.

Dickman left after the 1951 season to concentrate on his career as a radio/TV salesman; first at Capehart-Farnsworth, then at Stromberg-Carlson; both manufacturers of the day. Connie continued to model for household products after the war; brands such as Ipana toothpaste, Resistab cold tablets, and Super Starlac powdered milk. She was later the “Avon lady” for many years. The couple had a daughter, also named Connie, during the 1950s.

Emerson’s wife described him as a friendly man, which was an asset for his career in sales. Yet he had a sense of modesty and wouldn’t bring up his baseball career unless someone else brought it up first.

Dickman took interest in his kids playing sports. Second son Robert played in the Astros’ minor league system as a catcher despite suffering from polio as a child. Dickman also golfed after his career and helped Fred Corcoran set up tournaments for the PGA. His last job was with the Yankees. He was a group and season sales representative from 1975 until he retired in 1980.

Dickman died on April 27, 1981, at the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. He is buried in George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, New Jersey. In 1996 he was inducted into the Washington and Lee University Athletic Hall of Fame.

Sources

Interview with Dave Sisler on January 9, 2008.

Interview with Emerson Dickman III on May 9, 2008.

Interview with Connie Brescia on May 10, 2008.

Baseball-Reference.com

Ladies Home Journal, Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Boston Post,

Hartford Courant, New York Daily News, New York Times, The Sporting News

Stout, Glenn, and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000)

Special thanks to Rod Nelson.

Full Name

George Emerson Dickman

Born

November 12, 1914 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

Died

April 27, 1981 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.