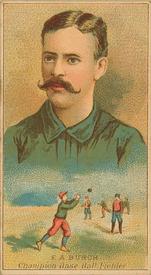

Ernie Burch

The advent of free agency for players in the 1970s provided hot stove league fodder for baseball fans with news of players, their agents, team owners, and lawyers negotiating multi-million-dollar contracts and perks such as tax-deferred annuities and all sorts of other inducements. Nearly 100 years earlier, all that one particular 19th-century free agent wanted was for the club to supply his uniform and an advance on his $250 a month salary, to help him make it through the winter. Even these modest demands were sticking points when a now-forgotten outfielder named Ernie Burch negotiated with four different teams during the winter of 1885-1886. He unwittingly became the subject of what newspapers across the country called “The Burch Case,” a contentious battle between the Brooklyn Grays and New York Metropolitans of the American Association over his contract rights.

The advent of free agency for players in the 1970s provided hot stove league fodder for baseball fans with news of players, their agents, team owners, and lawyers negotiating multi-million-dollar contracts and perks such as tax-deferred annuities and all sorts of other inducements. Nearly 100 years earlier, all that one particular 19th-century free agent wanted was for the club to supply his uniform and an advance on his $250 a month salary, to help him make it through the winter. Even these modest demands were sticking points when a now-forgotten outfielder named Ernie Burch negotiated with four different teams during the winter of 1885-1886. He unwittingly became the subject of what newspapers across the country called “The Burch Case,” a contentious battle between the Brooklyn Grays and New York Metropolitans of the American Association over his contract rights.

Ernest A. (no full middle name is known) Burch was born September 9, 1856 in Paw Paw Township in DeKalb County, Illinois, which is located in the north central part of the state, west of Chicago. His parents were Alfred W. and Lydia (Phillips), both natives of New York state and married in Cuyahoga County, Ohio in 1843. Ernie, as he was usually called throughout his life, had four siblings: older sisters Ellen and Marcia, an older brother Andrew, and a younger sister Ida. Ernie’s father Alfred was a farmer who purchased 40 acres of land for $50 in 1847 and later was appointed postmaster of the small village of LaClair in DeKalb County. His mother Lydia was missing from the 1870 US Census, and Ernie and his siblings, with the exception of the oldest, Ellen, lived with their father in DeKalb County. No divorce or death records could be found—it is not known what became of his mother.

No information could be found on Burch’s childhood or early ball playing but it seems likely he started out with area amateur or semipro teams. By the time of 1880 US Census, when he was in his early 20s, Burch had moved to Colorado and was employed as a broom maker, although the explicit reasons for the move were not stated. He made Denver his off-season home during his playing career where, in addition to his broom making trade, he also worked as a painter with the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. In June 1882, Burch first appears in a box score for the independent Denver Browns against the Leadville Blues in game that was billed as the “First Championship Game for the Base Ball Pennant in Colorado.”1 A number of young players who would go on to the major leagues got their start in Colorado in the early 1880s, including Dave Foutz, who pitched for Leadville.

Burch began his professional career in Organized Baseball back in his home state of Illinois with the Peoria Reds of the Northwestern League in 1883. An account from an October game against Rock Island singled out his defensive prowess noting, “Burch, centre field for the Reds, gave chase and when within a short distance from it, made a leap, jumping more than three feet from the ground, and caught it with his left hand. It was considered the finest play of the day and Burch was loudly applauded.”2 Later that year he was back in Denver playing for a picked nine and in the spring of 1884 returned to Peoria.

On Friday August 8, 1884, the Cleveland Blues of the National League were in Grand Rapids, Michigan for an exhibition game before moving on to Detroit for a four-game series. Prior to the game, three of the Blues top players, pitcher Jim McCormick, catcher Charles “Fatty” Briody, and shortstop Jack Glasscock, jumped the club to sign with Cincinnati of the newly formed Union Association. Reportedly, in addition to $1,000 bonus for each, McCormick was offered $2,500 and Briody and Glasscock, $1,500 each.3 Initially there were rumors, quickly denied by Cleveland team president C. H. Buckley, that the team might disband. Instead, replacement players were added, including catcher Jerry Moore from Terre Haute and pitcher John Henry of the Grand Rapids team the Blues had just played.4

Ernie Burch, available after his Peoria team disbanded in late July, was another of the replacement players added to the Cleveland club. He joined the team in Providence and made his major league debut against the Grays on August 15. Burch went hitless in three at-bats but drew a walk and scored a run off opposing pitcher Charles “Old Hoss” Radbourne in a 3-2 Providence win.5 It was noted, however, that Burch “…played a brilliant game in left field.” He played regularly over the last month and a half of the season, mostly in left field, but hit just .210 in 32 games. There was no interruption in the Blues schedule, and after the reorganization the team won three of four in Detroit but lost 29 of their last 36 games. Cleveland finished in seventh place in the National League with a dismal record of 35-77, 49 games behind pennant winning Providence.

Despite hitting just .210 Burch received moistly positive reviews. Late in the season he, along with second baseman George Pinkney and Germany Smith (who had replaced the departed Glasscock at shortstop) were considered “…the stalwarts of the Cleveland club.”6 In November, it was noted that even though he had not been reserved by Cleveland, “[Burch’s] chances are good, however, for a first-class engagement.”7 In December, it was rumored that Burch was negotiating with the Washington Nationals of the Eastern League, but instead signed with the Kansas City Cowboys of the Western League. He was hitting .361 after 26 games when he again was the victim of a franchise disbanding. When the Cowboys broke up in early July, Burch was quickly snapped up by Washington where he finished the season, batting .324 in 55 games as the team’s regular left fielder.

Washington D. C. fielded a team for four of the five years the National Association existed, including both the Olympics and the Nationals during the 1872 season. After playing independently the rest of the decade, the Nationals were members of the Eastern Championship Association in 1881, both the Union and American Associations in 1884, and the Eastern League in 1885. In 1885 a new National Agreement was adopted between the National League (NL) and American Association (AA), which removed the protection of the reserve system from all other “minor” leagues in the country. As members of the Eastern League, this ruling applied to the Nationals which essentially made all their players (including Burch) free agents.

As late as December 1885 Washington papers reported that Burch was penciled in as the Nationals (who would join the National League in 1886) regular left fielder for 1886.8 However, in November, Charlie Byrne, owner and manager of the Brooklyn Grays of the AA, used his considerable pull in the world of professional baseball to contact Francis Richter, editor of Sporting Life, who put Byrne in touch with his Denver (where Burch made his off-season home) correspondent A. A. Adams. Byrne asked Adams to contact Burch to inquire about his terms and act as his agent in signing Burch to a Brooklyn contract. Adams connected with Burch and on November 28 wired Byrne informing him, “Burch will play with you next season for two hundred and fifty per month with advance money.”9

At this point a third AA club entered the bidding for Burch’s services. One report suggested that Baltimore Orioles manager Billy Barnie balked at Burch’s demand for $250 a month salary and elected not to sign him. Another source reported that he had been signed by the Baltimore Orioles as early as October 1885 and was subsequently released.10 This was verified by AA President H. D. “Denny” McKnight, who, in a January 21 telegram to Byrne said, “By my record Burch belonged to Baltimore and so I wired Messrs. Byrne and Barnie. The latter informed me he had released Burch.”11 Sporting Life suggested Byrne and Barnie reached some sort of agreement, writing, “There was a wink and a nod, and presto, Barnie released Burch to Byrne of the Brooklyns, and pretty soon there was a buzzing all along the B line. Burch’s status was altered. He was now a released player.”12

Byrne initially objected to Burch’s terms, particularly his request for the advance money, so Adams wired back to his boss. “…must have some advance. This is his ultimatum. Has received offers from four other clubs. None yet accepted. Answer immediately.” Adams was referring the fact that there were rumors that a fourth team, Burch’s old Washington club, was still trying to sign him. To cover all his bases Byrne notified Nick Young, president of the NL, to be on the lookout for a Washington contract with Burch’s signature. Byrne then reluctantly accepted Burch’s terms and instructed Adams to have Burch sign an agreement to that effect with the understanding that a written contract would be mailed to Denver for his signature.

On January 6, Adams forwarded Byrne an agreement signed by Burch which read: [Denver Col., Jan. 5. – I hereby agree to sign a contract to play ball with the Brooklyn Base Ball Club of Brooklyn, N. Y. during the season of 1886, at a salary of $225 per month. It is expressly agreed, however, between the manager of the club and myself that he shall loan me the sum of $225 to be repaid to him out of my salary and that the club shall furnish all uniforms required by me. (Signed) E. A. Burch.13 Byrne cited Section 10, Article VI of the Association’s Constitution which implied that Brooklyn did not have to tender Burch a regular contract until February 4 (within 30 days of signing the January 5 agreement) and asserted that Burch’s written agreement was binding.

On January 7, Byrne mailed a blank contract and bank draft for the $225 advance but by January 14 neither had arrived in Denver. Adams wired Byrne notifying him of the fact and added, “Metropolitans agent here has made him big offer.” Another of the offers that Burch used as leverage in his negotiations with Adams and Byrne was from another AA team, the New York Metropolitans. Byrne learned that the delay of the contract and check reaching Denver was due was due to a winter snowstorm in the Midwest that blocked the railroad tracks and slowed mail delivery. Byrne arranged for a wire transfer of the $225 advance money with the Wells Fego office in Denver and promised that a duplicate contract would be sent.

Despite his signed agreement, no formal contract had reached Burch and he may have assumed Brooklyn was no longer interested in his services. Meanwhile, a Mr. Allen, an agent for the New York Mets had already arrived in Denver and, “…had been industriously at work working Burch, by superior inducements in the way of larger salary and advance money.” The Brooklyn contract finally arrived by mail on January 18 but Burch, before signing, decided to hear what the Mets had to offer. The salary figure was the same, $250 per month, but the offer of a $500 advance, double what the Grays offered, tipped the scales and Burch signed a contract with the Mets on January 21.

When Adams caught wind of this development, he notified his boss back in Brooklyn. That same day (January 21), Byrne fired off three telegrams: one to Adams, another to Burch, and a third to McKnight. In his wire to Adams he warned, “We shall insist in our right and Burch must sign his contract with us or he will not play at all.” In his missive to Burch, Byrne threatened, “Under our rules the agreement you made is binding, please sign contract now in Adams’ hands; any other contract you make is null and void.” His message to McKnight stated, “Please refuse to approve any agreement or contract signed by E. A. Burch, other than the one with Brooklyn. We shall hold him to agreement with us.” McKnight responded by saying that would approve whichever contract arrived in his office first.14 Burch, for his part, sent a brief, friendly response to Byrne stating he had declined to sign the Brooklyn contract, “…by the advice of the best counsel I can get,” and closed his telegram offering Byrne “kind regards.”

Burch never actually signed a Brooklyn contract, and the one he signed for the Mets arrived at McKnight’s office in Pittsburgh. However, on January 28, Byrne hand-delivered a copy the original agreement signed by Burch dated January 5. When the two documents were compared, it was agreed the signatures on both were that of Ernie Burch. Byrne further argued that the delay in Brooklyn’s blank contract reaching Burch in Denver was due to the snowstorm—a circumstance out of his control. Although Byrne could not explain how the Mets contract (which had to travel the same route as the blank Grays contract) arrived on time, McKnight ruled, on the basis of the earlier signed agreement, that Burch was the property of Brooklyn.

George Williams, secretary of the Mets club, protested the ruling on the grounds that in the new National Agreement contracts must be completed within ten days after acceptance of terms (snowstorm or not), not thirty as argued by Byrne. Williams also questioned whether or not Brooklyn had even sent a contract to Burch (Byrne produced a document showing his first mailing to Denver was postmarked January 7), stating that their [Mets] contract was mailed January 17 and reached Denver for him to sign by January 23, well within the ten-day window. Williams also contended that Burch’s January 5 agreement to sign a contract was not a contract, and therefore not binding. It was decided to resolve the issue at the AA’s spring meeting in Louisville on March 1.

The first order of business in Louisville was the “Burch Case.” After a review of all pertinent evidence, the directors present, which included Byrne representing the Grays interests and Williams advocating for the Mets, went into executive session and retunedthe following:

The board of directors find that on or about Jan 4, 1886, that E.A Burch furnished to the Brooklyn Base Ball Club the terms for which he would play with that club during the ensuing season, and that the Brooklyn club forthwith accepted the terms of said Burch by telegraphing to him in person, which amounted, in the opinion of the board, to a contract. We further find the contract made with the Metropolitan club on or about Jan. 23, 1886, was negotiated for and made by the Metropolitan club after they had received due and ample notice of the existence of the contract with the Brooklyn club, and for these reasons is null and void. The board of directors hereby decide that the Brooklyn club is entitled to the services of the said E. A Burch for the season of 1886.15

After his contract status was finally resolved, Burch married Anna Miller in Denver on March 22, 1886. Later that spring he reported to Brooklyn, where he had a solid year as the Grays regular left fielder, batting .261 in 113 games. His 72 runs batted in was good for ninth place in the AA. Burch returned to Brooklyn in 1887 and was batting .291 when he sustained a knee injury in a game against the Philadelphia Athletics on June 30 at Washington Park in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Citizen reported he was hit by a pitched ball,16 while the Daily Eagle said it was a knee sprain.17 The exact nature or extent of the injury was not reported but he played sparingly over the next three weeks.

It’s not clear what role the injury may have played, but apparently there was still some lingering bad blood between Byrne and Burch over the previous contract situation. The Grays began a four-city western road trip in early July and Burch was left behind by Byrne during their stop in Louisville. The reason given was “indifferent ball playing”18 and Byrne was quoted as saying that “…he didn’t care whether he ever saw him [Burch] again.”19 He was formally released by the Grays on July 21, and Burch left Brooklyn with a sour taste in his mouth saying, “…he will not play ball professionally for a living again.”20

Thus concluded Burch’s major league career. In three seasons: part of 1884 with Cleveland of the NL, and all of 1886 and part of the following season with Brooklyn of the AA, Burch batted .260 in 194 games. Among his 200 big league hits were four homers, ten triples, and 30 doubles. He scored 134 runs and knocked in 105. The 5-foot 10-inch, 190-pound outfielder who threw right and batted left-handed, played almost exclusively in left field (185 games) and appeared in nine more in right.

After his unceremonious departure from Brooklyn, Burch initially inquired about hooking on with a semipro team in his hometown of Denver but when he asked for a $150 advance of his salary for moving expenses, the offer fell through. He ended up with the St. Paul Saints of the Northwestern League for the balance of the 1887 season, and apparently showing no ill-effects from his leg injury, batted .322 in 43 games.

Burch was released by St. Paul that October and he joined up with the St. Louis Whites of the Western Association in 1888. That club disbanded in late June and Busch’s whereabouts the rest of that season and in 1889 are not entirely clear. There is no record of him playing in Organized Baseball and the Denver papers did not report on him playing with any area teams, but there is strong evidence he was playing semipro ball in South Dakota. An item from July 1888 said, “Burch, the captain of the Redfield nine belonged to the St. Louis Whites before that club disbanded.”21 Burch also played with Redfield and Aberdeen during the 1889 season and may have had some connection to the area. In getting in shape for the 1887 season with Brooklyn it was reported that Burch, “… has been hard at work on a ranch in Dakota this winter and is in fine condition.”22

He was back in Illinois by 1890. A report from Springfield that May listed “Burch, lf,” in the lineup for a team called the “Train Room.”23 Given that left field was his natural position, and he had been employed with the railroad back in Colorado, it’s likely this was Ernie. Shortly thereafter he joined the Peoria Canaries of the Central Interstate League and by June he was named manager of the club. He hit .301 in 73 games for the Canaries. Burch returned to Peoria in 1891, this time with the Distillers who were playing in the Northwestern League. This would be his final season in Organized Baseball.

Sometime after the 1891 season in Peoria he relocated to Guthrie, Oklahoma. Perhaps the reason was a business opportunity, as he partnered with a man named Atherton in a broom factory on Oklahoma Avenue in town. He was still playing some independent ball, legging out a three-bagger in a game against Oklahoma City in May 1892 that “made the audience hoarse.”24 In early June, the local paper reported that, “E. A Burch is on the sick list today”25 and four months later that he had died of typhoid fever on October 12, 1892 at the age of 36.26

After Ernie’s death, his widow Anna returned to Denver where she worked as a dressmaker and remarried in 1916. She died in 1925 and her remains were returned to Guthrie, where she was buried next to Ernie in the Summit View Cemetery. Burch left no known descendants.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Jonathan Greenberg and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics from Burch’s playing career are taken from Baseball-Reference.com and genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com.

The author also used information from clippings in Burch’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Most of the information regarding Burch’s contract negotiations and subsequent decision came from the February 3 and 10, and March 3 and 10, 1886 issues of Sporting Life.

Notes

1 “Blue Vs Browns,” Denver Republican, July 3, 1882: 5.

2 “Yesterday’s Game,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, October 11, 1883: 5.

3 “A Terrific Shock,” Cleveland Leader, August 9, 1884: 8.

4 “Cleveland Will Not Disband,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1884: 7.

5 “Sporting News,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 16, 1884: 3.

6 Cleveland Leader, August 29, 1884: 4.

7 (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, November 10, 1884: 2.

8 “Washington’s Nine,” Washington (DC) Daily Critic, December 11, 1885: 4.

9 “The Burch Case,” Sporting Life, February 10, 1886: 3.

10 Washington (D. C.) National Intelligencer, October 25, 1885: 5.

11 “More Trouble,” Sporting Life, February 3, 1886: 3.

12 “The Burch Case Again,” Sporting Life, March 3, 1886: 3.

13 “More Trouble.”

14 “More Trouble.”

15 “The Association: Details of the Spring Meeting at Louisville,” The Sporting Life, March 10, 1886: 2.

16 “Close, But Tiresome,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 30, 1887:2.

17 “A Strong Game,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 30, 1997: 2.

18 Rocky Mountain News, July 18, 1887: 6.

19 Brooklyn Standard Union, July 21, 1887: 4.

20 Brooklyn Citizen, July 25, 1887: 2.

21 “Redfield Vs. Aberdeen,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) News, July 18, 1888: 3.

22 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 27, 1887: 7.

23 Illinois State Journal (Springfield), May 9, 1890: 5.

24 “Hurrah for Guthrie,” Oklahoma State Capital (Guthrie, Oklahoma) May 28, 1892: 6.

25 “Personal,” Oklahoma State Capital, June 11, 1892: 1.

26 “Sudden Death,” Oklahoma State Capital, October 15, 1892: 1.

Full Name

Ernest A. Burch

Born

September 9, 1856 at DeKalb County, IL (USA)

Died

October 12, 1892 at Guthrie, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.