Eusebio Gonzalez

One of the more obscure players in Red Sox history, Eusebio Gonzalez was the first foreign-born Latino to play for the Bosox. Eusebio Miguel Gonzalez Lopez was born in Havana, Cuba on July 13, 1892. Batting right and throwing right, he was an infielder listed as 5’10” with a playing weight of 165 pounds.

Gonzalez sparkled occasionally as a ballplayer but his baseball career is a difficult one to research. Author Jorge S. Figueredo finds Gonzalez’s first professional season in 1910 with the Fe baseball club which played in Havana’s Almendares Park during an 18-game season, February to April.

A perusal of the Havana newspaper Diario de la Marina indicates that the first professional game for the 17-year-old Gonzalez appears to have begun at 3:00 pm on February 10, 1910 in a 3-2 loss to the Almendares team. He played shortstop and batted seventh for Fe. He was 0-for-4 on the day, with two putouts, two assists, and two errors. On February 13, he recorded his first base hit, going 1-for-4 during a 7-1 loss to Habana; it was a tough day in the field: he committed three errors, with one assist and no putouts. Figueredo shows Gonzalez hitting .152, with seven hits in 46 at-bats during 16 games. He was credited with one triple and one home run.

Gonzalez is listed as appearing in just three games in the 1910-11 season; Fe disbanded in March. He is not known to have played at all in 1912.

In 1913, he played for Almendares, another Havana ballclub, with just two hits in 20 at-bats, but that winter during the 1913-14 season, he was back with Fe and hit .244 with 21 hits in 86 at-bats. This is when he was first spotted by an American baseball man.

When the Cincinnati Reds visited Havana in the fall of 1908, they were defeated more than once by Cuban teams and left the island impressed with the quality of play of a number of men. In 1910, the Reds signed Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, and both debuted with Cincinnati in 1911. Both the Philadelphia Athletics and Phillies also visited Cuba, as did the Detroit Tigers (Gonzalez may have seen Eustaquio “Bombin” Pedroso’s 11-inning no-hit game against the Tigers in 1909), the New York Giants, and more. Roberto Gonzalez Echeverria notes that the 1917 Spalding Guide listed 23 Cubans in organized baseball by 1914.

Eusebio Gonzalez had come to the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers captain Jake Daubert while the Dodgers were playing a series of games in Cuba in early November, 1913. Playing first base and leading the league in hitting with a .350 average, Daubert had won the Chalmers trophy as the most valuable player in the National League for the 1913 season. Beginning on November 1, the Brooklyn team played a number of games against Havana, Almendares, and Fe. The games were hard-fought, and Brooklyn lost the first two games before winning three in a row on November 8, 9, and 10. After the final game on November 13, a 5-4 Dodgers victory, Daubert spoke at the Herodia Theater and “complimented the Cuban teams in their ball playing, asserting that his club won only after the hardest kind of playing.” [New York Times, November 14, 1913]

Bozeman Bulger of the New York World wrote during the series that Daubert had spotted a prospect. “A young fellow, Gonzalez by name, has been doing such wonderful work for the Havanas that Daubert has offered $3,000 for his release to Brooklyn. He believes the young Cuban will make one of the greatest infielders in the world. During the season, which is now at its height in Havana, Gonzalez has batted better than .400 and covers almost as much ground as Arthur Devlin did in his palmy days.”

Bulger added that Daubert “had the young fellow practically signed before he learned that Wilbert Robinson had become manager of the club, but that has not stopped his efforts. He promises to turn the wonderful Gonzalez over to Robby in the spring.” How Gonzalez ended up playing in the New York State League remains unclear. He was reportedly signed by the Troy (NY) Trojans team in the State League on March 24, 1914. The March 28 edition of the Troy Times reported that Gonzalez and a Cuban pitcher named Rodriguez would set sail from Havana to New York on April 4, and that Trojans manager Hank Ramsey would meet them in New York.

The impending arrival of Gonzalez was noted in stories in the Troy Times, such as April 8’s “Cubans Delayed in Their Trip” which informed readers that Ramsey was about to set out to meet the two Cubans when he received a telegram advising him that they had “failed to get reservations.” That very evening, though, the Cuban players turned up at Troy’s training facility in Hackensack, NJ. They arrived accompanied by the “representative of a newspaper in Havana. Neither of the players can speak English but their escort said they would know enough before the season starts.”

Ramsey was apparently pleased, as the April 10 paper wrote that Gonzalez “was tried at shortstop and surprised the rest of the squad with his speed and the amount of ground he covers.” His first appearance was in a pre-season game against Bridgeport on Friday, April 10. He played second base, made one error, was 0-for-1 at the plate but reached base, stole two bases and scored a run. The team’s next game, against Waterbury, saw “some sensational plays in the field” by “the Cuban infielder.”

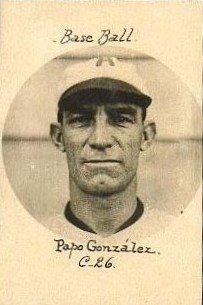

Throughout the year, both Troy newspapers – the Times and the Record – routinely referred to him as Gonzales (with the “s”), or “the Cuban,” or occasionally (in the Record) Senor Gonzales or Mr. Gonzales. Nowhere in their coverage was there ever any sense of disapproval or controversy noted regarding the inclusion of a player from Cuba on the Troy baseball team. Newspapers of the day, throughout his career, routinely rendered his surname as Gonzales which helped occasion confusion since during 1914 there was another Gonzales playing for Scranton, also in the New York State League. Eusebio Gonzalez, however, spelled his name with the “z” as his signature on a 1974 letter sent Cliff Kachline at the Hall of Fame indicates. He signed that letter, in his shaky 81-year-old script, as “Eusebio Gonzalez Lopez (Papo)”. Diario de la Marina also consistently spelled his name with the final “z.”

In Cuba, he was widely known by the nickname “Papo,” a nickname which does not turn up in American or Canadian newspapers.

Coverage of other pre-season games accorded him “best stick work” honors in one contest and in a win over Hartford, the Timeswrote, “Gonzalez was the fielding star.” The April 13 Record noted of one early game, “Gonzalez carried the laurels…the Cuban showed some fast work in the field and is picked as a winner.”

On Opening Day, April 30, Troy played in Scranton and beat the Miners, 4-2. Gonzalez played third base and was 1-for-2 with two stolen bases. In the fifth inning, he walked, stole second, went to third as the throw from the catcher sailed into center, and scored on a single, resulting in his first run scored in American pro ball. Gonzalez was signed as a utility infielder, and before the season was more than a month underway, he had played at each of the infield positions. He’d batted as low as seventh, but also batted both leadoff and cleanup. He was up and down in the order, and frequently moved around the field, though not often at first base.

No note at all was taken of Gonzalez’ first days of play in the New York State League in Diario de la Marina‘s deportiva section. Two Cubans in the major leagues (Armando Marsans and Mike Gonzalez) received some attention: a May 4 headline read “Marsans esta batando sobre 300” and note was taken of Mike Gonzalez (no relation) as “Otro cubano que honrara a su patria.”

An astonishing number of games were rained out in the first month of play, resulting in significant financial losses for Troy’s owner and a lot of idle time for the ballplayers. Eusebio’s first name was never mentioned once; the same was true with most of the other players. He made the news fairly often, though. The first big game of his year with Troy came on May 10, when he was 2-for-4 with a double. The Troy Times noted, “Notwithstanding the fact that Gonzalez is unable to speak English, the opponents of the Troy team do not put much over on the Cuban. Baseball is the same no matter what language the players speak and Gonzalez knows the game.” They might have left off there, but went on to add, “Apparently he does not have much trouble knowing when he had three strikes or four balls.”

The pitcher Rodriguez was released the next day, with the ambiguous comment that he “found it hard to get into condition.” Gonzalez, though, was an immediate hit with observers of the game, and the May 21 Times stated, “Gonzalez adds to his popularity every game he plays. In the first inning he made a wonderful catch of Deal’s line drive that had all the earmarks of a safe hit when it left the bat.” In the second inning, his relay cut down a Wilkes-Barre Barons runner at the plate. During the game on May 21, he came into a game against Scranton as a pinch hitter in the top of the ninth. He beat out an infield hit to second base, was bunted to second base, and – one out later – scored on a single for the go-ahead run in a 6-5 win. The team – often called the Troy Collarmakers by the Record in reference to the Cluett-Peabody Company, a major employer in the city – held first place for all of May, but dropped to third place by mid-June. The June 23 Times tossed in a line referring to a well-executed double play: “The Cuban always has his mind on the game.”

By July 7, there was mention in the local papers that the Troy team was looking for new ownership to take over the franchise. The asking price was $2,000 plus the assumption of an unspecified number of debts. Some of the debts were apparently to the players and manager Ramsey; much later, the Binghamton Press wrote on September 8, 1914 that the Troy ballplayers had not been paid since June 1. Ramsey in fact left the team in July (perhaps under a bit of a cloud related to some form of gambling and possibly even game-fixing) in order to attempt to settle some of his personal debts. There were some discouraging times, such as the game against Syracuse on July 27 when the Stars had a 13-0 lead over the Collarmakers after just two innings. Gonzalez offered to take the mound and help, the Record reported. “Senor Gonzalez tried to make it plain that he knew how to serve up the benders, but deaf ears were turned in his direction. Mr. Gonzalez was lucky to keep out of the fierce picture.” Just three days later, though, Troy came back from a three-run ninth-inning deficit to beat Utica, 5-4. “The hero was Mr. Gonzalez, for he delivered a blow to center field that brought victory.”

Another ninth-inning drive led to an August 26 headline in the Record: “GONZALEZ OPENS FIRE UPON MINERS IN NINTH.” He hit a double, moved to third on McChesney’s single, and scored on a couple of Scranton misplays, for the 4-3 Troy win. The Elmira Colonels clinched the State League pennant on September 10, and Troy lost a final doubleheader to Albany on September 13. The Times said that Gonzalez “inserted some fine fielding plays during the afternoon and this helped in the distribution of enthusiasm.” Troy finished well out of the running. In the 19 years of State League play, they remained the only team never to win a pennant.

Gonzalez finished with a flourish, though, 3-for-5 with a double and a triple in the first game, and 1-for-3 with a double in the second. With Troy, the right-handed Gonzalez played a full 126 games, batting .264 and (with 41 errors) a .947 fielding average. Many games in this era had a high number of errors, both due to the much smaller gloves used by fielders and the less than immaculate field conditions.

The Record‘s wrapup of the season asserted that, though pitcher George Winter (a former Red Sox pitcher) would become a free agent, most of the players were reserved for the following year under baseball’s reserve clause. It was noted, though, that “the future of State League baseball in this city as a whole is a matter of conjecture.”

Eusebio Gonzalez returned to Cuba after the season was over. In winter ball, Gonzalez played for Habana, batting .180 in an even 100 at-bats over 33 games.

At least during his initial discouraging experience with American professional baseball at Troy, he had made an impression on a team with deeper pockets. Manager John C. Calhoun signed Gonzalez to play for Binghamton (New York State League) and signed him as a free agent, apparently possible given the Troy club’s failure to pay him his full 1914 salary. This was totally unexpected by Lew Wachter, Troy’s new manager, and by the Troy club’s ownership. They had been counting on Gonzalez playing for them in 1915.

The Binghamton Bingos in 1915 played at Johnson Field under the ownership of George F. Johnson. The team operated, as did the league as a whole, under a salary cap of sorts – $2,500 per month for the total team player payroll. Most players received no more than $200 per month, down from $250 in prior years due to the great turmoil in organized baseball caused by the Federal League and other “outlaw” aggregations, and a great deal of legal scuffling ensued. Teams often only truly came together in early April, on the very eve of the exhibition games. As late as April 9, an item in the Binghamton Press informed readers that Troy threatened “to put up a fight for the return” of second baseman Gonzalez. The day before there had been a general meeting of State league magnates and both Troy owner Magill and manager Wachter arrived “armed with many documents in support of their claim that the Elmira and Binghamton clubs were not acting within their rights” in signing James Catiz (to Elmira) and Gonzalez (to Binghamton.) Those meeting agreed with Troy in the case of Catiz, but in the matter of Gonzalez, “nothing definite was done.” The Troy newspapers believed he would be returned to Troy, but workouts on Centre Island began without him and in the end he played out the year and into the 1917 season with the Bingos.

Eusebio was said to be “pleased with the outlook for a good season with Binghamton.” Trying out for the team were two other Cuban ballplayers – Francisco Lujan and Jose Gutierrez, but neither made the club. The fact that they participated in the exhibition season indicates that the Binghamton team certainly had no qualms about putting Cuban ballplayers on the field. In fact, on April 30, the Binghamton ballclub defeated (6-4) a visiting team of Cuban stars featuring a number of noted players such as the right fielder Magrinat. At one point, Gonzalez was decked by Lujan’s pitch. The Press story indicated that both Lujan and Gonzalez had been talking to the other team “in Cuban” and the brushback seemed to result from some of the words exchanged. The paper added that “the dark complexioned athletes can talk in Spanish and jitney bus at the same time.” “Jitney bus” was apparently a kind of dance done in contemporary vaudeville.

Even though the Binghamton newspaper was prone to some of the casual ethnic slurs of the day (one headline about a pitcher from Hawaii read “Chink Flipper to Join Redlegs”), it never exhibited any sense of animosity to Gonzalez or any of his compatriots who may have played for the Bingos. Coverage typically referred to him simply as “Gonzalez” or “the Cuban” but never pejoratively. There was no indication that the use of “the Cuban” was other than a handle being used to make writing the columns more varied. In the two and a half years Gonzalez played in town, one finds no evidence that he was considered any less than any other player on the Binghamton ballclub.

Opening Day 1915 saw Binghamton beat the Scranton Miners, 6-4. Gonzalez went 2-for-4 on the day. His former team, the Trojans, was still struggling financially and failed to turn up for a series of three games scheduled to begin at Johnson Field on June 1. The games were all forfeited to Binghamton, but after new ownership assumed control of the Troy team, league officials gave them a break by rescinding the forfeits and rescheduling the games. Given the costs incurred by Binghamton, though, the Press deemed this an “injustice.” One of the new Troy owners was Johnny Evers of the Boston Braves. In April 1916, Evers divested himself of his interest in the team, a move “practically demanded” by the Braves, who argued that they were paying him a full salary and wanted 100% of his concentration.

Gonzalez was a spirited player and got himself thrown out of at least one game, on June 11. The newspaper account referred to his “limited supply of English words” and suggested that perhaps the umpire tossed him “largely because the Cuban could not talk back.”

His batting suffered in the first couple of months, and his average had dipped under .200 near the end of June, though he began to rebound on June 25 with a single, a triple, and a fielding play dubbed “sensational.” He doubled and tripled on June 26, but even the four hits only raised his average to .197. The team, however, was tied for first place as of June 29. A week later, on July 7, the Press sportswriter declared of Gonzalez, “His work at third has been nothing short of sensational.” His average inched up over time, thanks to stretches like the late-July three-game sweep of Scranton when Gonzalez went 5-for-10 with two doubles and a triple. By August 2, he was hitting .238, still not as strong as the year before with Troy, but headed in the right direction. His fielding was rough at times, and one of the few headlines he earned during his time with Binghamton read “Gonzalez Is Away Off in His Fielding” – he’d committed three errors and cost the game. Gonzalez finished the season with 40 errors and a .899 fielding average. He batted .258 on the year, according to the Press, which also ascribed him 21 doubles, 12 triples and one home run. Speedy on the basepaths, he had 35 stolen bases. Handwritten statistics found in Hall of Fame files are similar, but not identical, indicating fewer errors (36) and a higher batting average (.268.)

Binghamton won the pennant, clinching it on September 3 with a win over Elmira. For winning “the rag,” manager Calhoun was immediately rehired for the 1916 season. Gonzalez played with Habana again that winter and had a terrific Cuban League season, batting .349 in 32 games, with 37 hits in 106 at-bats – and showing more power, with seven doubles and four triples.

Gonzalez showed up a few days late for the start of the 1916 season, but was in fine shape after the Cuban season and hopped right into the lineup at third base on April 23. Both Troy and Albany were no longer in the New York State League, replaced by two teams from Pennsylvania – Harrisburg and Reading. Gonzalez once more played virtually every game of the season until suffering a serious injury during the second inning of the August 24 game against Harrisburg. Gonzalez was blocking second base to take a throw when Harrisburg’s Cook slid into him hard, badly bruising his left leg. As a result of his injury, he was finished for the season. Syracuse took the pennant and the Bingos finished third. In his second year with Binghamton, Gonzalez played in 111 games, with 360 at-bats, hitting .272 with 34 stolen bases.

Again, Gonzalez played winter ball in Cuba, this time – as though foreshadowing later developments – for the Red Sox! Not the Boston Red Sox. Author Gonzalez Echeverria explains that the year was an unusual one; while the new Almendares Park was being built, there was a short-lived one-year competition between three teams known as the Orientals, White Sox, and Red Sox from January into March. Gonzalez hit .226 in 14 games.

In 1917, Charles Hartman took over as Binghamton’s manager. There was a communication problem indicated in the April 25 newspaper, as spring training was well underway: “Slugging Gardener and Gonzy Still Listed As Missing Bingos” read a subhead. The “gardener” in question was outfielder Bill Kay, consistently the team’s best-hitting player. Hartman said he had no idea where they were and was reported as “considerably disturbed.” The very next day, though, it was reported that Gonzalez had sailed from Havana on the steamship Savannah “several days ago” and was expected in New York shortly. Indeed, he arrived that very day. It was expected that Gonzalez would “jump right in and flash brilliant form” and he did hop into the April 28 game without seeming to miss a beat. On May 2 – opening day – he was 1-for-4, with a double, and stole third, scoring on a single a few moments later. One of the best days he had in a Bingos uniform came on May 25. Gonzalez was 4-for-5 with a solo home run in the ninth inning over the left-field fence in Scranton. Binghamton won, 12-8. As of June 7, he was batting .267, pretty much in line with his record for the three previous seasons in New York State League play.

The World War was heating up, conscription was implemented, and baseball owners were uncertain as to whether they would be able to continue to field teams. At midpoint in the season, in July, they called off the season, but then reversed course somewhat, scheduling a “second season” beginning with a new set of games (and dropping the Utica and Harrisburg ballclubs from the league.) As part of the retrenchment, the salaries for Binghamton players were cut by $53.37 per month, or they were offered their outright release. The final game for the first season was July 8 and the Binghamton papers show Gonzalez finished the season playing third base, batting an even .260. Other records show him as 61-for-224 in 66 games, with the same .272 average he had posted in 1916.

When the second season started on July 11, Eusebio was no longer with Binghamton. The July 23 Springfield (MA) Daily Republican headlined his signing with the Springfield Green Sox. The main sports page headline read “Green Sox Sign Cuban Infielder.” The accompanying story reported that Gonzalez had signed with the Eastern League team, saying that he “has been playing a whirlwind game for Binghamton up in the New York State league, and was only set adrift when talent became a drug on the market in that circuit. Manager O’Hara has been on his trail for some time now, but did not land him until Saturday [July 21].” The Republican noted that he would play third base for the injured Johnny Mitchell, adding, “He is a big, rangy fellow, quick as a cat, and a natural hitter, according to the New York State league writers who have watched him perform this season.”

Playing for owner William E. Carey’s Springfield Green Sox, Gonzalez became a local favorite. His first day saw him go 1-for-2, and he scored the winning run in the top of the 10th inning, having walked and then moved to second on a single. He stole third and went on to score when the New London Planters pitcher threw the ball into left field. The paper said that his work “stood out as the prominent light of the Springfield incandescent squad.” The July 29 paper said that “Eusebio Gonzalez has won a place in the hearts of Springfield fans already in spite of his name – Bill Carey says Eusie’s folks make a fine grade of wine in Spain and that’s what makes the young man sparkle so.” Attempts to learn more about his heritage, the vineyard, his parents’ occupation, and the like have proven fruitless.

After his first full week in the Eastern League, he had gone 8-for-21 and scored four runs. The July 30 paper declared, “Gonzalez has proved why he was popular up in the New York State league.” Springfield went on a tear, winning 17 of 25 games, and the August 25 Republican wrote, “‘Eb’ Gonzalez keeps the old head up there all the time. He pulls down some mighty hard hits and difficult chances during an afternoon.” The next day’s paper ran a photo of Eb and called him “Springfield’s leading hitsmith…polling them at the rate of .319.” He’d been 2-for-4 at the plate and made several “snappy plays.” He was referred to as “Senor Gonzalez.” On the 27th, it was noted that “Gonzy” had come to the attention of some big league scouts: “Prominent during the week in the play of the Sox has been the work of Eusebio Gonzalez. ‘Gonzy’ has been hitting well up with the leaders and his fielding has bettered any infield stuff seen on the local lot for some time. His work has been so good that at least three major league scouts have been attracted, and it will not be surprising if he is lifted out of class B baseball when the drafting season comes along.”

The season ended on September 8, with Springfield in seventh place. Despite the various encomiums accorded him, in the time he was with Springfield during the second half of 1917, he committed 22 errors and had a fielding average of .873. His average was fourth highest on the team, though, and local paper concluded, “Gonzalez was a big addition to the club and played good ball here all the way, in spite of his fielding average. He was particularly strong in the pinches, both as a fielder and sticker.” Game stories very occasionally called him “the Cuban” but for the most part he was straightforwardly described simply as Gonzalez. The uses of nicknames like “Eusie” and “Eb” and “Gonzy” reflected positive feelings about the man.

Gonzalez spent the winter months in Cuba once more “at his Havana home,” reporting a little late in 1918, on May 9. Green Sox manager O’Hara was serving wartime duty at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts (and heading up the shipyard nine.) Eastern League teams agreed to play with 13-man rosters. On May 11, former Red Sox shortstop Freddy Parent was named manager of the Springfield team and workouts began on May 15. Parent assigned himself to play short and positioned Gonzalez at third, saying, of Gonzalez, “This boy should have a fine season. He is not only fast on his feet but he is quick in the head. He learns rapidly and responds quickly to advice. The Cuban anywhere in the field can give a good account of himself.”

Gonzalez was in good shape and the Green Sox took the May 22 Opening Day game against the visiting Waterbury team, 6-3 at League Park. He was 0-for-4 at the plate, but the Press reported “Gonzalez rising above all other performers by one especially clever stunt when he flashed in on a slow grasser, picked it up with one hand and with little further ado pegged unerringly to first base ahead of the runner. The Cuban was unusually spry.” The paper assessed the team, adding “Gonzalez and Parent, it is safe to say, are likely to be favorites with the fans.” Eusebio was 3-for-4 in the second game of the year.

As the season progressed, Gonzalez had the pleasure of playing third base when Paddy Green threw a no-hitter against Hartford on June 4. It was far from being a perfect game, though; both Gonzalez and Parent made errors in the game, and Green walked five. He continued to earn recognition for spectacular fielding plays; the June 9 paper praised a play that Gonzalez made behind third base, a play that “belonged in the big leagues. Gonzy is the third baseman of the Eastern League.” Given the small rosters, it wasn’t surprising that he played every game. What was a pleasant surprise was his early season batting; after the first 27 games, he was hitting .365, second on the team. Springfield, though, was in sixth place. In the last week of June, both Gonzalez and the Green Sox went into a slump.

On July 2, another Gonzalez joined the Springfield Green Sox. Ramon Gonzalez, Eusebio’s brother, was signed and played second base. He had only played a handful of games when the Eastern League held discussions about suspending the rest of the season. Attendance was down dramatically. The Providence Greys were hit the hardest, only drawing about 200 fans to each game. The Press mentioned the two brothers in its July 16 edition: “Eb Gonzalez spent a busy day at third, handling five chances without trouble, and came through with two solid smashes which totaled three bases. Both Eb and his brother, Ramon, limped badly during the game. Each has a lame pedal extremity.” Ramon played shortstop, Parent moving to second base.

On July 19, U. S. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker announced that baseball was “non-essential” to the war effort and the Eastern League decided to close up shop. The Springfield paper headlined a sports page story “Gonzy Local Star; Majors Spotted Him; Chance Probably Lost.” The gist of the story was that owner Bill Carey had received a couple of offers for Gonzalez – a prime commodity of sorts, because being a Cuban national he was not subject to the U. S. military draft. But since the major leagues were also talking about terminating their season as well, the opportunity might have passed. The paper concluded, “Fans would have liked to have seen the Cuban given a trial. He has played remarkable ball for Springfield and has been the real life and hope of the club all season.”

It was good news, then, when the July 24 edition let readers know that Gonzy had been sold to a major league ballclub. “Eusebio Gonzalez, the crack third baseman of the Springfield Green Sox, was sold yesterday by Magnate Bill Carey to the Boston Red Sox.” He was due to join the Red Sox as their train passed through Springfield at 12:25 pm en route to Detroit to play a series with the Tigers. The newspaper offered the opinion that it was not surprised in the least, because “all who seen him perform have realized all along the speedy Cuban was major league timber,” and added that Gonzy “should have been there long ago.” As for Carey, he said, “Gonzalez is the fastest and hardest working baseball player I have ever had on my club and I have never seen any in the Eastern league that could touch him.” The paper said that “all of Springfield wishes Gonzy the best of luck in his new undertaking.”

Gonzalez debuted for the Red Sox in Chicago on July 26, later an auspicious date in Cuban history. He entered late in the game, a replacement for Everett Scott at short in a game the Red Sox were losing to the White Sox, 7-1. Eddie Cicotte was pitching an excellent game for Chicago, holding Eusebio’s teammate Babe Ruth to an 0-for-4 day. Gonzalez got his first major league at-bat in the eighth and he tripled. Jack Stansbury singled, driving in “recruit Gonzalez” and bringing the score to 7-2.

Back home in Havana, there was a brief acknowledgement of Gonzalez’ debut. Diario de la Marina offered a modest sports page headline reading, “Papo Gonzalez debuto con gran suerte en el Boston Americano pegando un triple en su unica excursion al bate.” Diario’s coverage of major league ballgames typically consisted of the boxscore and a line or two about the game. The boxscore of the Boston game had a heading “Una Gonzalez Mas” and the accompanying game story seemed to indicate that the article’s writer was not 100% sure which Gonzalez it was playing for the Red Sox. The text read: “Suponemos que el Gonzalez que figura en el line up bostoniano sea Eusebio Gonzalez (Papo) el jugador habanista que hasta hace poco pertenecio a la New York Estate League.” Given the relatively few Cubans who had made the major leagues, it seems remarkable that the game story scribe didn’t even know which Gonzalez it was; they just knew it wasn’t Mike. It was, instead, una Gonzalez mas, and he speculated that it was Papo. The sports page headline writer had it right. Nonetheless, there was no particular attention accorded the native Cuban upon his debut, nor was there in the weeks to come – no feature, no player profile, no photograph. The Springfield Republican was far more interested in Gonzalez than Havana’s Diario de la Marina.

Two days later, Gonzalez again filled in for Scott in the later innings. Facing Reb Russell, who had an 8-0 shutout going in the top of the ninth, Gonzalez made an out in his one at-bat. His average was cut in half, from 1.000 down to .500. Paul Shannon of the Boston Post commented on Gonzalez’s work in the eighth inning: “Gonzalez made two pretty plays in the inning.”

At least one other baseball man had his eye on Gonzalez. A story out of St. Louis on August 3 in the Ft. Wayne News and Sentinel said that Branch Rickey of the Cardinals was reported interested in the Gonzalez brothers, both Eusebio and Ramon.

Eusebio’s third appearance in a Red Sox game came in Detroit, on August 6, and he played a full game at the hot corner. He was 1-for-3 in a game that was tied 4-4 after nine innings. Gonzalez led off the 10th and drew a walk. Wally Schang got on due to a Detroit error, and then Carl Mays walked. Bases loaded. Tigers pitcher Rudy Kallio fielded Hooper’s grounder and threw home to cut down Eusebio and start a double play, but the throw went all the way to the backstop and two runs scored as the Red Sox took the lead when Gonzalez crossed the plate. Dave Shean drove in a third run. Mays gave up one run to the Tigers in the bottom of the 10th, but the Red Sox won, 7-5.

A very brief note was provided in the August 7 Diario de la Marina: “El cubano E. Gonzalez, defendio la tercera base con gran exito, al campo y al bate.” That was it. The Cardinals’ Mike Gonzalez made the headlines that day, and he, Dolf Luque, and Marsans all received some occasional attention.

All told, after three games for Boston, Eusebio Gonzalez had played error-free ball in the field, batted .400 with a triple, and scored two runs – but he never got another chance to play in the big leagues.

The Red Sox played two more games on the road trip, August 7 and 8 in Detroit, then headed for home to host the Yankees. Gonzalez was exempt from U.S. military service, but the Sox also had Dave Shean (too old for the draft) and manager Ed Barrow was bringing in a number of other players. George Cochran debuted on July 29 and played most of the games at third. Everett Scott stuck at short, playing out the games, which were mostly relatively close ones. Holding first place, one Globe report said the Red Sox were “nonchalant leaders” but there was plenty of roster activity and the same account noted, “Nobody had been canned during the day and none of the athletes had received any hit-and-run signs from their draft boards.” It was nonetheless a close pennant race, with the Red Sox holding about a three-game lead for most of the following week. Gonzalez did return to Boston with the team and presumably was fitted with a home uniform, but never wore it competing in a game at Fenway Park.

Sportswriter Arthur Duffey, writing in the Boston Post, seemed to connect with Gonzalez, even though he managed to misspell both first and last names. As far as Duffey knew, Gonzalez was likely to be around for a while. In the August 8 Post, Duffey wrote, “Ensevio Gonzales, the new recruit corralled by the Red Sox, is pining to figure in a world’s series if only to run for someone else. Of the several Cuban players who have come to this country within a decade Ensevio is the only one who has had any chance to compete in baseball’s big classic. He states that if he gets this opportunity he will be a bigger man than the governor of Havana when he returns home in October.” The Boston Traveler called him “Eusebo Gonzales” and the Boston Herald announced him as “Octavio Gonzales.”

Why didn’t Gonzalez play more than the three games for Boston? In his book Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, Nick C. Wilson points out, “During the course of that season the Red Sox field-tested five utility players at shortstop; Gonzalez was the only man who lasted more than one game. It may seem strange that a rookie who hit a triple off one of the best hurlers in the American League in his first at-bat was treated so indifferently.” Wilson then raises a couple of questions: “Was he too dark-complected to bring back to Boston? Did his previous minor league club demand too high a payment for his services?” Asked about the conjecture, Wilson replied that he was just guessing, trying to figure some reason why the Red Sox let the draft-exempt Gonzalez go. The compensation answer seems unlikely, given what we know of his departure from Springfield, and the fact that he finished the season with Toronto. The Red Sox were the last major league club to sign an African American player, so it’s not surprising the question of color comes to mind. These weren’t the Yawkey years, though. There was different ownership at the time — Harry Frazee. During the first 20 years of the Red Sox franchise, the team had previously signed two Mexican-American ballplayers (Frank Arellanes and Charlie Hall) and also a full-blooded Native American (Louis Leroy.) There was no indication in the Boston press that Gonzalez or any of these other Red Sox players were controversial signings due to their ethnicity.

When the Red Sox returned home from a 15-game road trip, the title was still very much up for grabs, and Paul Shannon of the Post foreshadowed their arrival, writing how much the Boston fans were looking forward to return of a reanimated Babe Ruth and also the opportunity to see George Cochran, “a brilliant fielder, a clever base runner and the best man that the Red Sox have had at third base since Fred Thomas was called by the draft. Cochran is a heady base runner, a fair hitter and a good run getter.” Therefore, apparently an improvement over Gonzalez in manager Ed Barrow’s estimation. As it happened, as soon as Cochran hit Fenway, he began to slump seriously, so Barrow brought in former Boston Brave Jack Coffey (he’d last played in the majors in 1909) from the Tigers, to take over the third base duties. All evidence seems to point to Barrow ranking Gonzalez third amongst his choices for third base.

Gonzalez did play for the Red Sox during one game in New England, an August 18 exhibition game against the New Haven Colonials in Connecticut. He played shortstop and batted second, but was 0-for-4 at the plate (with one sacrifice hit.) Two days later, he was in a Toronto Maple Leafs uniform.

Because of the World War, it had been agreed that the 1918 major league season would end early, around September 1, and that a World Series would be played, to finish by the 15th. The Boston Globe reported on August 20 that Everett Scott, Stuffy McInnis, Harry Hooper, and Amos Strunk had each heard from their draft boards that they would not be called before September 15. The talent needs of the organization were becoming clearer, and apparently Barrow felt that Gonzalez was surplus. Teams were starting to discharge their players wholesale, relieving themselves of any contractual responsibilities that might attach despite the season being shortened. Before the game on August 22, every member of the St. Louis Browns was notified that he would be released effective September 2.

The first-place Red Sox didn’t need Gonzalez that badly and Barrow had looked to see if he could cut a deal elsewhere. The Toronto World reported that Barrow had wired Toronto manager Dan Howley “asking if he could use Infielder Gonzalez. Dan wired back to hurry him along. The Leafs did have a need. Shortstop Joe Wagner was unexpectedly called to report to his draft board in New York, and it looked like Gonzalez could fill the bill.

Gonzalez joined the Maple Leafs on August 20, playing shortstop. The World acknowledged his arrival by writing, “He came via the Boston Red Sox route, and the gentleman from the warm isle is very acceptable. He displayed all the earmarks of a real ball player. He is fast, knows how to run bases, and is a good fielder.” Gonzalez singled in the first inning, stole second, took third on an error, and scored easily on a drive that rattled around in front of the left-field bleachers. That was his lone hit in four at-bats. The Toronto Star praised his “right-smart performance,” saying he “fielded cleverly, showed a strong whip, and hit and ran the bases as if he knew how.” The Star mistakenly gave him the name Ramon Gonzales.

Even after he’d gone to the Red Sox, the Springfield Daily Republican followed Gonzy’s play. After his debut, the paper reported his “brilliant start,” wrapping up the brief account with an exhortation: “Keep it up Gonzy.” An August 7 headline read “Gonzy Is There” and said, “Gonzy performed brilliantly.” After Gonzalez had moved on to Toronto, Republican coverage waned.

Gonzalez played both halves of a Toronto twinbill on August 21, going 3-for-6 with an RBI double, a stolen base, a sacrifice, and turning a double play. He made three errors in the two games, though he got on base frequently and scored six runs in the two wins over Hamilton.

When the Leafs won again, against Rochester the following day, they took first place in the International League race. Eusebio singled and scored the tying run in a six-run bottom of the eighth inning that lifted them to a 6-4 lead. Rochester failed to score in the ninth and Eusebio joined in the celebration. Two stories in the World said that “pandemonium broke loose” and the Toronto players “danced like a lot of crazy kids.” The World noted that “Gonzalez turned handsprings in the joy of the moment,” a dozen in all.

Playing second base and batting second, he scored the first run in the next game, and on August 24, he was involved in one of those kinds of plays that champions seem to turn: the ball was hit to him, he “reached for it with his gloved hand, the ball deflecting off the glove to Dolan, who made a grab for it, but couldn’t hold it, he knocking the ball in the air about three feet, and Gonzalez, swinging around, grabbed it with his bare hand, and threw the runner out at first.” The Maple Leafs played excellent ball and held on as the race came down to the wire. As of August 30, Binghamton had taken a slim statistical edge, .686 to .685. Both teams won that day, Gonzalez hitting a bases-loaded single to drive in two, the second of which sufficed to beat Jersey City.

On August 31, Toronto and Buffalo were tied in the bottom of the ninth. Cosy Dolan walked, Gonzalez sacrificed him to second, and Lear singled Dolan home to win the game. Come September 2, Binghamton beat Baltimore in the first of two, winning 2-1, while Toronto beat Buffalo, 4-1. If both teams won the second game, or both teams lost, the pennant went to Binghamton. Baltimore reversed the score and pinned a 2-1 loss on the Bingos. The Toronto/Buffalo game was hard-fought. It was 3-3 after five innings. In the top of the 10th, Buffalo took a 4-3 lead, but the Leafs didn’t quit. Dolan singled, Gonzalez sacrificed him to second. Callahan popped out. With two down and Dolan on second, Lear singled him in to re-tie the game.

Neither team scored in the 11th, and Buffalo was set down in the top of the 12th. Then word arrived that Binghamton had lost. In the words of the World, the “fans went crazy with excitement.” A win would give Toronto the flag. Otherwise, Binghamton took top honors.

Gonzalez already had two hits on the day and two stolen bases, had executed a sacrifice perfectly, and “pulled sparkling work on ground balls.” He also played a crucial role in the final frame. The Leafs’ Heck popped up to the second baseman, ranging deep, but the Buffalo right fielder bumped his teammate just after he got his glove on the ball, dislodging it. Dolan sacrificed Heck to second and Gonzalez was up once more. He drove a single to left field, putting Heck on third base. Gonzalez ratcheted up the pressure, with a steal of second. Buffalo walked Callahan on purpose, and the fielders all moved in. Lear slammed the first pitch he saw far over the center fielder’s head for “one of the longest hits of the season,” and the International League pennant.

Even if he were no longer with the Red Sox, Gonzalez had still helped to secure a pennant in 1918 – and apparently enjoyed the experience immensely. The Maple Leafs barnstormed a bit around Ontario in the following week, beating city teams in St. Catherine’s, Brantford, and Ingersoll, and eventually Gonzalez set sail for home.

In fact, Papo Gonzalez played with three pennant winning teams in 1918, in three different countries, appearing for Boston, Toronto, and Havana.

Gonzalez played for Havana (with his brother Kakin) and they won the 1918-1919 Cuban League championship. “Papo” was the nickname accorded Eusebio and “Kakin” that given Ramon. Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria reports that Havana (Papo was joined by his old teammate Lujan, who’d played in 1915 pre-season exhibition games with Binghamton) also won a 1919 Campeonato Oriental in September 1919.

Papo was a little late arriving for spring training 1919, due to passport problems, but he was in such good shape from winter ball that it didn’t cost him any playing time. His first big game of 1919 came on May 15. He reached base all five times he was up, stole two bases, and scored four times. His defense won acclaim as well. In a loss on May 25, Eseubio (the Toronto Star came up with a new spelling) was 2-for-3 and scored two runs, while making “several remarkable stops and throws.” He showed a little fire on the 28th, as Toronto took first place with a 5-3 win. In the sixth, he was trying to turn the double play when Buffalo’s Harris gave him a “hard bump.” In retaliation, Gonzalez threw the ball at Harris and hit him. “The fight was on in earnest. Rights and lefts flew thick and fast. Jabs, counters, and side steps went thick and fast. Gonzalez tried several haymakers that flew over Harris’ head, while the latter tried for the Cuban’s solar plexus, getting in one blow. They were warming up nicely when the players and the bluecoats stepped in between the combatants.” Both were ejected; Gonzalez was suspended for one game.

Gonzalez was still remembered fondly by fans in Binghamton, and when he first appeared there for Toronto, on June 19, he “was given a great ovation when he stepped to the plate in the first inning.” For much of the year, Gonzalez was the Maple Leafs’ leadoff batter. He played shortstop all year, off to a spectacular start, hitting as high as .377 by May 24. He slipped into a prolonged slump, though, and wound up batting .247 in a full 146-game season, with 127 hits in 515 at-bats. His 22 doubles and 36 stolen bases stand out. Two of the steals came on August 3 in Rochester. It was a tie game in the top of the 10th. He singled in one run and then, with runners on first and third, drew a throw on the front end of a successful double steal that gave the Leafs a 3-1 lead.

In the 1919-20 Cuban season, playing for Habana, he hit a much lighter .181 in 72 at-bats.

Returning to Toronto in 1920, Gonzalez had an excellent year, batting .297 in 121 games playing second and third base. He hit 16 doubles and four triples and his highest total yet in stolen bases: 38. He often earned praise for other parts of his game, too, helping turn four double plays in the May 26 game against the Rochester Colts and scoring from second on a sacrifice in a game on June 24. On August 20, he “showed the fans an honest-to-goodness Ty Cobb slide when he scored in the sixth by throwing his body way to the back of the plate and getting the rubber with his toe.” (Toronto Star) The season ended with Baltimore taking top honors. On a personal level, the season showed marked improvement, as the Star noted in a wrapup that began by mentioning the 50-point increase in his average and the fact that he’d stolen two more bases. “His fielding was just as good, if not better, than last.”

Gonzalez stuck around Toronto for a few extra weeks, and it cost him when he was at the Woodbine race track of the Ontario Jockey Club. He was jostled in the crowd of 15,000 race fans and a pickpocket boosted his billfold out of an inside pocket, costing him $255 in American money. He left for the Caribbean on September 30.

Back in Cuba, he played for Almendares in the 1920-21 season, batting .257 and leading into his best year in the International League. Deep in spring training, the Star suggested that he was primed for another great year: “Gonzalez played ball all winter in Cuba, and is in splendid condition. He is pegging [the] ball around the bases with all kinds of speed, and the other players wince every time they catch one of his throws.” There was one amusing moment, during an exhibition game in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. “Gonzalez hit one, a line over the left field fence, and through an open window in a house at the end of the park.” (Toronto Star)

Playing under manager Larry Doyle, Gonzy started the 1921 season at second base, usually batting seventh. He even had the opportunity to play against his former Red Sox teammate Babe Ruth in a May 9 exhibition game when the New York Yankees visited Island Stadium, Toronto. The Babe hit a home run his first time up. Gonzalez had an 0-for-4 day.

A better day at the plate was one that counted, July 6, against the Jersey City Skeeters. Gonzalez drove in five runs with three hits. Doyle had moved him up in the batting order, and he typically batted second. Playing Syracuse near the end of the month, he doubled and scored in the 11th inning, giving the Maple Leafs the win. Toronto was mired in fourth place, though, and going nowhere. In 1921, Gonzalez had an exceptionally good season, playing in 160 games, with 581 at-bats, and hitting .301 with 60 stolen bases, six triples, and 28 doubles. Why the Boston Red Sox didn’t purchase him and give him another try (Boston finished in fifth place in 1921 and in last place in 1922) remains an open question.

Gonzalez played for Havana again during both Cuban seasons, later in 1921, and again in early 1922. Early in the Leafs season, he was beaned by Brown of the Reading Miners, the ball “hitting him fair on the forehead…It knocked the Cuban unconscious and he was carried to the club house where two doctors ordered him to the hospital…He bled freely from the nose.” (Toronto Telegram, April 21, 1922) They ordered him to remain in hospital for 48 hours observation, but extended his stay when recovery took longer than initially anticipated. The team suffered. “There was naturally not the work around second that Gonzalez’ presence would have given. That pop that counted for two in the seventh would have been easy for the Cuban,” wrote a later Telegram.

It was not until May 5 that he was able to return, in a game when Reading visited Toronto. One of his teammates exacted a little revenge. Brown was pitching once more, coming on in ninth-inning relief. The Leafs had runners on second and third with nobody out. Brown’s pitch hit Wingo in the ankle, and Wingo went out to confront the Reading pitcher. “With the Gonzalez incident rankling the big autumn-haired outfielder sallied Brownward and promptly took it out of that gentleman’s hide. He did a splendid job of it and Brown is apparently a far better sharpshooter than a battler at close range.” (Telegram) Both teams rushed onto the field, but things were kept under control and both Brown and Wingo ejected. Gonzalez came in to run for Wingo.

The next day, there was some concern that Gonzalez might be “ball shy” as a result of being hit on the head, but his first time he laid down a beautiful bunt and his second time up he hit a “slashing double to right, effectively laying that shy idea at rest.” (Telegram)

The season ended in an unfortunate fashion. His average was off, and the Toronto Star suggested, “Gonzalez is weakening under the strain.” On August 3, though, he drove in four runs and on the 10th, he tripled to lead off the ninth, sparking a five-run rally that lifted the Maple Leafs to a 5-4 win over Reading. On the 17th, in a game against Jersey City, Ensobio (sic) tripled, doubled, and singled twice. But in a game against Newark on August 26, he “failed to run out a hit, and when reprimanded by the manager, grew indignant. He claimed that the ball hit him on the hand. They had some hot words then and there on the diamond with the fans looking on.” (Toronto Globe & Mail) The incident soured some of the sportswriters, who suggested that his heart wasn’t in the game. The paper continued, “Gonzalez’ case is one that will require some thinking and a decision on the part of the Toronto club before they decide to retain him for another year. The Cuban played great baseball last year, stealing 60 bases and batting close to .300 but he has not done so well under the Onslow regime, and this is only to be expected when it is realized that he does not wish to play for Toronto.”

A later edition on the paper reported on an August 28 exhibition game against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers, explaining that Gonzalez had been taken out of the lineup, and then added a little more fuel to the mounting fire, writing, “This fellow is apparently satisfied that his days with the Leafs are numbered and when he made little or no effort to do anything on the defensive, and fanned twice in a row, he was benched, and the fans roared their approval. Last year Gonzalez was one of the best fielders in the International. This year he is not. It is unfortunate for him and his major league aspirations that he should have failed so dismally with the Tigers on hand and scout Dick Rudolph of the Boston Braves occupying a box seat.” (Globe & Mail)

The Star said that the fans got on Esnbeid (the oddest spelling yet) Gonzalez “when it was apparent that his mind was not on his work.” He was taken out of the game by manager Onslow, and though he showed up for the train to Montreal did not accompany the club. “The bells are tolling for him. Next spring the Leafs will have another second baseman.” The next day, the Star added that Gonzalez had “asked to be relieved from duty” and that it was “beginning to look as if the Cuban has about outlived his welcome around here.”

The truth of the matter came out shortly afterward. Gonzalez had a broken bone in his hand. He had indeed been hit by a pitch on the 26th. He shouldn’t have been shown up by his own manager. He shouldn’t have been asked to play in the later games. The Star apologized more or less, allowing, “His poor showing against Detroit is thus accounted for. Many players would not have attempted to go on the field at all with an injury of this nature.” His season was over. He was unable to grip a bat or throw a baseball. There was some fear that he would be permanently disabled.

He played second, third, and short for Toronto in 1922, his average dipping to .274, appearing in 118 games. This winter, he chose to stay in Canada rather than return to Cuba. His hand healed, though, and he was able to hop into an “all-stars” game against some old-timers in mid-October.

A big reason he stayed in Ontario became clear on November 25, 1922. The Toronto Star headlined a story “Gonzy’s New Contract” that told readers Gonzalez was “making the greatest double play of his life…signing a life contact this morning in Barrie.”

The Barrie Examiner explained, “Congratulations to Miss Audrey Jary and Mr. Eosebeo Gonzales who were married here on Saturday. Mr. Gonzales is a famous baseball player.” Yet another spelling for Sr. Gonzalez. They got his name right on the marriage license, though. Recorded on November 30, the license reflects the November 25 marriage between the 22-year-old stenographer Audrey Redverse Jary (daughter of Arthur Jary and the former Martha Ellis) and the 28-year-old Eusebio Gonzalez. Both listed the Church of England as their religious denomination. Gonzalez indicated his residence at the time of marriage as Toronto. On the marriage license, Gonzalez gave his profession as “professional ball player.” His parents were said to be Eusebio Gonzalez and Florinda Lopez. The senior Eusebio was listed as a native of Havana, Cuba.

So, too, was the bride’s father, in what would appear more likely to be an error on the license. Arthur Jary died on March 29, 1939 at age 73. His obituary in the Examiner described him as a native of Norfolk, England who had lived in Craighurst, Ontario, for 51 years. His wife died later in the year, on December 2. She had been born in Newton Stewart, Ireland. Martha Jary was a “woman of great purpose…a fine mother” and took pride in making rugs and quilts. Arthur Jary had been in the hotel business at first, and then became active in coal and grain, in charge of the local grain elevator at the time of his death. He was very active in his church, his lodge, and Conservative politics. One wonders at the family’s reaction to Audrey’s marriage to the baseball player from Cuba.

As 1923 began, the Leafs once again had Dan Howley as manager, and Howley had added another Gonzalez to the mix, Eusebio’s brother Ramon, who’d played shortstop for Springfield since 1918. Ramon had been signed to the Toronto ballclub in early January. Asked how he’d deal with two Gonzalezes in the same infield, Howley told the Globe & Mail, “I’m going to simplify this thing by calling one of them ‘Pat’ and the other ‘Mike.’” The newspaper explained that Ramon had been playing winter ball for the Santa Clara team in Cuba. However, “Eusebio (‘Mike’) Gonzalez is wintering in Toronto and district, and has gained sixteen pounds in weight since the season closed last fall.” No baseball and maybe a little home cooking?

Ramon wasn’t so easy to deal with. Ramon had come off back-to-back years of .313 and .314 with Springfield and was looking to cash in a bit. He was slow to arrive for the season, happy enough with the salary he’d been offered, but holding out for a percentage of the purchase price paid to Springfield, which he claimed he’d been promised verbally. Something was worked out and the “swarthy third baseman” (Toronto Star) soon turned up. Howley had said he was thinking of alternating the Gonzalez brothers at third, but room was found for both of them.

Even though “Mike” (with the middle name of Miguel, this wasn’t as far-fetched as it might seem) reunited with his old manager, who’d taken over from Onslow, he wasn’t the player he’d been. He was maybe a bit out of shape, in any event reporting a sore arm in late March. The hand seemed to have healed but one speculates that perhaps a little of the fire had dimmed, perhaps in part due to the unfair treatment he’d suffered at the end of the 1922 campaign. There was one incident early in the year when Eusebio didn’t run out a grounder, and Howley read him the riot act, “told him if he intended to keep his place on the team he had to run out every time.” He was fined $50 and benched for a bit.

Three weeks later, on May 12, Ramon was hitting at a .296 clip, but Eusebio was only 20-for-79, a .253 average. On June 20, he had tonsilitis and lost a few more days. Finally, at the very end of June, Eusebio was sold to the Eastern League’s Waterbury Brasscos in Waterbury, Connecticut. He hesitated to report immediately, wanting to work out terms to his satisfaction, and as late as July 5 was reported to still be in Toronto. The Globe & Mail said, “He was a spectator at the game yesterday” but that he was “anxious to get away from Toronto…the Cuban is a good player when he cares to hustle, but his heart was not in his work here.”

In his sixth season with the Maple Leafs, he appeared in 46 games at second and third, before being sent to Waterbury, where he played exclusively at shortstop. For Toronto, he hit .249; for Waterbury, he hit .254 in 70 games. Ramon finished the year for Toronto, batting .281.

Eusebio’s arrival in Waterbury was occasioned by considerable confusion. We’ve already noted some confusion trying to track Eusebio Gonzalez in the historical record, and the variety of spellings rendered of his first name. The “Pat” and Mike” names may have prompted some confusion as well. Keep in mind that it Ramon who was “Pat” and Eusebio who was “Mike.” At least Toronto newspaper characterized the two as “the near Cuban twins.”

Waterbury’s mid-season acquisition was headlined in the June 30 Waterbury American: “Brasscos Buy Gonzales From Toronto and Land New First Sacker, Also.” The story began, “Ramon (Mike) Gonzales, star shortstop of the Springfield club last season, was purchased from the Toronto club of the International league today by the Brasscos for a sum said to be in the neighborhood of $3,500. He is expected here tomorrow and will break into the lineup at once.” The story said that Toronto had purchased him from Springfield the year before, for the same sum, and concluded, “Gonzales is popular here and besides being a flashy fielder with a powerful whip, he is a hard hitter.”

Two days later, though, the American reported, “Ramon (Mike) Gonzalez, former Springfield shortstop, who was scheduled to report to the Brasscos yesterday, didn’t report and probably won’t.” There was a dispute between the two clubs because Waterbury thought they were buying Ramon Gonzalez, but “Toronto thought the local club was bidding for his brother Eusabe, another former Eastern leaguer, having pastimed with Springfield before going to the International.” Eusabe (note the newspaper’s spelling) was a second baseman, and it was a shortstop that Waterbury sought.

Three days later, the Thursday newspaper said that Gonzalez was “still on his way to this city from Toronto. Eusabe forgot to wire whether he was coming by way of San Francisco or was taking the shorter route through Norway and the Azores. At any rate, not a word has been heard from the quiescent Cuban since he set out from Toronto, Sunday morning, for the City of Brass.” He finally arrived in time to play the July 9 game and earned a headline “Gonzales Adds Pep to Brassco Outfit; New Shortstop Fields Position Well and Also Gets Two Safe Bingles.” The game story in the American spelled his name Euscabe Gonzales. The Waterbury Republican noted his debut as well, spelling his name Eustabe Gonzales and describing him as the “celebrated Cuban shortstop and member of a family of ball players.” Were there other brothers as well?

Our Gonzalez played shortstop and a little second base. He didn’t hit all that well at first, and usually hit low in the order, rarely earning a mention in game accounts. One exception was the July 26 Press subhead, which read: “Silent Mike Gonzales Comes Through With Hit In Last Frame Which Sends Albany to Defeat.” A five-run top of the ninth gave the Brasscos a 6-5 win. Silent Mike hit a solid single to center and reached third on a throwing error to the plate, scoring a moment later on a wild pitch. Waterbury, though, had been a fifth-place ballclub in the eight-team league when Gonzalez joined them, and failed to improve substantially. When Hartford’s Lou Gehrig hit a home run in both games of a doubleheader swept from Waterbury, the Brasscos fell to the cellar where they finished the year. This despite the fact that by mid-August, Gonzalez himself was batting .307. He began to tail off, though, and finished the season with a .254 average in 252 at-bats for Waterbury, just a little higher than the .249 he’d hit with Toronto in the season’s first 46 games. Gonzalez was seventh from the bottom of the list of league hitters published in the Press at year’s end.

The Waterbury papers usually simply referred to him by name, as either “Gonzales” or “Mike Gonzales” but never by nationality as, for instance, “the Cuban.” When Springfield’s Herrera came to town, he was called “the Cuban” but Eusebio Gonzalez was typically treated the same as any other player.

The off-season was an interesting one. Figueredo reports Eusebio as playing with Almendares but reports that statistics for the winter season are not available. However, the January 13, 1924 Diario de la Marina shows him playing second base for Habana, and he played a number of games for them, typically batting seventh and playing second yet apparently not playing particularly distinguished ball. He can be found in the boxscores, but he very rarely appeared by name in the game accounts. Bartolo Portuondo took over at second for a stretch of about 10 days in late February, but Gonzalez was back by the game of the 25th and finished out the season with Havana.

A report in the Toronto Star the following day said that he might be back in the International League in 1924, playing for Rochester. He’d apparently been released by Waterbury and signed by the Rochester club. Ramon was playing winter ball and “going great guns” but Eusebio was said to be taking the rest of the winter off and “spending his time and money trying to pick winners at Oriental Park.”

Speaking of guns, when “Mike” reported to Rochester spring training at Haddock, Georgia (near Savannah) to prepare for another season of International League play, he brought a shocking story with him: Gonzalez had been shot – by a sportswriter(!) – in Havana. Shot in the hand. The March 30 Rochester Democrat and Chronicle noted that “Eusibio (sic) Gonzales (sic)” had arrived in camp and would make a strong fight for the second base slot. The next day’s paper had a story headlined “GONZALES WORKING OUT AT SAVANNAH Cuban Player’s Injured Hand Improving Rapidly.”

The dispatch said that he was working out under the supervision of coach “Kaiser” Wilhelm. It informed readers that he was “late in reporting to the Rochester Club, because of a bullet wound in his wrist….The injury was not serious, the bullet making a slight flesh wound and grazing the wrist bone.” He was reported as confident that within a week or 10 days he would be in perfect condition. The news a week later was that his hand had “entirely healed” and that he was “training hard.” The April 12 paper, though, was not as optimistic: “Gonzales’ hand seems to be getting worse instead of better. The bullet fired by a Havana sporting editor has left its mark and it is a question how long it will be before the Cuban is able to play with the Tribe.” Because the wound had not responded to treatment, it was X-rayed and he was referred to a specialist in New York City for surgery. “A small bone in Gonzales’ hand is proving troublesome and it is likely that this bone will have to be removed.” It was thought that he would recover quickly, and be back in a week or two.

How had Gonzalez been shot? González was playing for the Habana Leones (also known as the Rojos) in the Gran Premio of 1924. Come the aftermath of the March 9, 1924 game, in which Habana had beaten Santa Clara, and per David Skinner’s translation of the March 10 article in Diario de la Marina: “As the fans were exiting Almendares Park following the game, three gunshots rang out behind the main grandstand. This attracted the reporters, and when they arrived on the scene they saw Habana third baseman Manuel Cueto and backup catcher Eugenio Morín trying unsuccessfully to protect a teammate with a wounded hand from apprehension by several policemen led by a Sgt. Ortega. That player turned out to be Rojo second baseman Papo González, who was taken into custody by the lawmen, to the dismay of [Marina reporter] Peter, who referred to him as one of the most admired players for his modesty and gentlemanliness.”

Conte was charged with the shooting and released on $200 bail.

W. A. Phelon’s column in the March 20, 1924 issue of The Sporting News provided a fuller description of the incident and its protagonists. It is worth reprinting here in its entirety:

Here in Cuba, they sure take their baseball seriously — and in the old-time way. If a sporting writer pans a player, good night! He has to whale the athlete, hand to hand, or be disqualified forever. A few days ago, Pepe Conte — well known to all American writers — penciled a paragraph that hurt the proud spirit of one Gonzales (not the noble Miguel) second baseman of the Almendares Club. Senor Gonzales sought out Senor Conte during the eighth inning, and smote him on the nose, proboscis, or snoot, so that Senor Conte fell extremely prone.

Senor Gonzales trumpeted in triumph, but not for long. Senor Conte uprose, and with him came a dark blue automatic, and, one instant later, Senor Gonzales lay upon the reddened soil. Then all Cuba went to war; and the strife between the partisans of Senor Conte and Senor Gonzales endured, with many casualties, until the police charged from several directions and bore everybody to the hoosegow. The doctors say that Senor Gonzales will recover. The judge says Senor Conte is out on bail. And, as might be expected, in the tumult and confusion, somebody took a darn good kick at the umpire. Isn’t it a wonderful world?

What transpired with Pepe Conte after the shooting? The Toronto Star provided a little more information, recounting the story told their reporter by Emilia Zarzo, a catcher for another ballclub who was “a cousin of the brothers Gonzalez.” Zarzo said that Eusebio was not seriously hurt but had been shot in the hand by Havana sportswriter Conte during an altercation on the field. “Zarzo maintains that Gonzalez was protecting himself against an attack by Conte when a bullet penetrated his left hand, inflicting a minor flesh wound. Ramon, according to the story told by Zarzo to the Canadian press, was involved in the dispute and summoned to court as a witness.” Zarzo might have tried out for Atlanta or Macon, or another Florida State league team training near Georgia but does not appear in enough games to have made the record books.

Gonzalez arrived in New York on April 13, registering at the Grand Hotel. The April 14 Democrat and Chronicle said the wound had been “inflicted by a Havana sportswriter.” The surgery was apparently successful, and the April 26 edition cited Gonzalez as in Rochester working out with a few pitchers and awaiting the arrival of the rest of the team in preparation for opening day. He expected to be ready for manager George Stallings. However, the same paper reported another mishap: “While walking across Main Street yesterday, the Cuban twisted his ankle. Though painful, it is not serious.” In fact, he didn’t get into a game until May 16. The Democrat & Chronicle reported, “This was Gonzalez’s maiden effort in the league for this year and it was a noble start.” He batted second, went 3-for-5 with one run scored, singling each of his first three times up, each one to a different field. He handled six chances in the field without an error.

The following day’s game account transitioned him from “Eusibio” to “Mike” and read: “The injection of Mike Gonzales into the team at second base has added plenty of hitting power to the team, the Cuban socking the apple for three safeties on Friday and coming through with two on Saturday. He bungled one easy chance in the field on Saturday but his all-around fielding has been first class, particularly on one play…The ball bounded in front of second where the Cuban grabbed it and touched second to force Thevanow coming from first. It was quick work on the Cuban’s part and brought a big round of applause from the bleacherites.” On May 30, he had himself a four-hit day in a doubleheader against his old Toronto teammates and in a game against Toronto nearly a month later he collected two hits in one inning, part of a 12-run fourth inning. The day after that, though, the headline read “Gonzales Gives Toronto Four Extra Runs with Error” – he’d been trying to turn a double play with a throw to teammate Fred Merkle when the ball slipped out of his hand. The newspaper was generous: “It was a bad break against the Cuban, who is playing great baseball for Stallings’ team.”

There was one oddity, dating back to May, though, the game against Newark in which he was sent in as a pinch runner, but “the Cuban…did not have on the same uniform as his teammates and the Bears objected.” Stallings sent him to the clubhouse to change. The Bears complained that the game shouldn’t be held up waiting for him to put on the right uniform, but the umpires allowed the change.

Ramon Gonzalez never turned up for Toronto in 1924. He was reported as “sulking” in Havana, holding out. He was said to have “decided to remain in Esperanto, Cuba and become a family man.” After being added to the suspended list in late April, another report indicated he was “repentant” and had cabled from his plantation in Esperanto. As late as May 26, with Eusebio already playing for Rochester, he said that he “cannot understand why Ramon decided to quit the Leafs. He advances the opinion that Ramon had been well treated here and had no reason to be a hold-out. Mike also made the announcement that, contrary to general opinion, Ramon is the older brother of the two.” (Toronto Globe & Mail) Such biographical information as we have shows Eusebio born in 1892 and Ramon born in 1897; the announcement only clouds the picture. Ramon had batted .281 for Toronto in 1923.

The May 28 Globe & Mail said that Eusebio “has been playing great baseball since the injury to his hand mended. For some time it was feared that Gonzalez would not be able to play again after he was shot in the hand by one of those remarkable sporting writers in Havana. The gunman was bonded over to keep the peace, and escaped a jail sentence. Gonzalez stated that there is no lack of excitement when the Cuban teams, all the players being armed, swing into action. Half the spectators are also armed.”

By season’s end, Gonzalez had quite a good season for Rochester, batting .278 with 7 triples and 21 doubles, driving in 57 runs in an even 500 at-bats spread over 133 games.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the gunshot wound, early 1924 had proven to be his last season playing winter ball in Cuba.

Gonzalez played three more seasons in U.S. ball, and just a bit of a fourth. He surfaced in the Texas League, playing for San Antonio in both 1925 and 1926. Ramon joined him there in 1925 (Ramon had finally joined New Haven in 1924, playing in 76 games and batting .253.) The pair were introduced to San Antonio newspaper readers with a bit of a joke on St. Patrick’s Day 1925. A photograph in the newspaper was bore the headline “Begorra! Here’s Pat and Mike” and the cutline read, “Above are shown the Gonzales boys, Bob Coleman’s brother team, which will be one of the features of the Texas League this season. Ramon, the ‘Pat’ member of the firm, probably will be the utility infielder of the Bruins. Brother Eusebio, alias Mike, is the keystone guardian. Both brothers came from the International League, Mike from Rochester and Pat from Toronto. Mike is 30 years old and Pat is 27. The brothers are natives of Havana, being graduates of the same Cuban amateur team that produced Luque, Mike Gonzales, the St. Louis catcher; Palermo, Dibut and Calvo of Fort Worth and other stars in the major and minor leagues.” Bob Coleman was the manager of the San Antonio Bears. Now there is a reported three-year gap in their ages, not a five-year one, but Eusebio is the older of the two.

Eusebio made a good impression early in the year, and the San Antonio Express said “the crowd went wild with delight” when he drove in three runs in a 21-10 rout of Houston on May 3, Gonzalez banging out both a home run and a double in the first inning, both off reliever Alva Sellars.

During the 1925 campaign for the San Antonio Bears, he played a number of positions and a spring training summary in the San Antonio Express found his play sound. The March 10, 1926 issue looked back on 1925: “Gonzales is the Cuban who came here from the International League last year and proved himself a capable player in every position in which he was placed.” He’d gotten in a good full 1925 season – perhaps his best one ever – batting .306 with six home runs and 58 RBIs. Both were career highs; the home runs were the first ever recorded. His 180 hits, his 36 doubles, and 238 total bases were all career highs, too. Ramon played less than 10 games for San Antonio.

There was mention of Gonzalez in a season-ending story telling where all the players were going, indicating that Gonzalez still had a strong accent: “Mike Gonzales he pool out for-a Habana in about wan week.” But he wasn’t heading for Havana, at least not to play ball.

The reason Gonzalez stopped wintering in Cuba wasn’t to avoid gun-toting sportswriters. It was that he suddenly took up an interested in skiing! And not water skiing, either. The San Antonio News reported him joining the Bears, competing (as always) for the second-base slot: “Mike Gonzales, the peppery Cuban second-sacker who spends the winters skiing around Craighurst, Ontario, Canada, checked into the Bruin training camp Wednesday and jumped right into the flock of rookies to battle for the regular keystone guardianship.” (March 3, 1926, San Antonio News) Of course, it’s possible that the sportswriter was exercising a little license here in suggesting time on the slopes.

Another San Antonio newspaper noted the change in circumstance: “Mike Gonzales arrived during the afternoon, but did not get into uniform. Mike got in on Tuesday night from his home in Toronto, looking fit. Mike’s native home is Cuba, but as he married a Canadian girl, he now spends his winters in Canada. ‘I find that since I quit playing winter ball, as I used to do in Cuba, I feel much better in the spring,’ he said. ‘I believe playing winter ball makes one stale, and that a rest during the winter is a good thing.’” Asked if he’d been ice skating, he simply said he’d tried to. He also said he’d had his tonsils removed and was consequently in better shape. “I weigh 170 pounds now,” said Mike, “while before I weighed around 155 and even went as low as 150, and thought for a while that I would have to quit baseball.” (March 4, 1926, San Antonio Express)

Not only had he not quit, but his life had changed and he sounded more content. Ramon started the season with Waco, also in the Texas League, but played most of his games with Tulsa, a Western League team. It was his last year in North American pro ball. In May, the Globe and Mail noted the two brothers playing for different Texas teams and squeezed in one more misspelling: Ausebio.

Eusebio’s 1926 production was off from the highs of ’25, but he nonetheless played a good full year at the middle two infield slots, getting in another 445 at-bats, batting .258 with 39 RBIs. He was homerless again, but struck 25 doubles.

In 1927, Eusebio Gonzalez turns up back in New England once more, back in the Eastern League playing for the Hartford Senators. He first turns up in a lineup on April 22, according to SABR researcher Gary Goldberg-O’Maxfield, playing right field. Goldberg-O’Maxfield reports, “Hartford was skippered by Kitty Bransfield in 1927 and early in the season, Hartford’s stadium (Clarkin Field) burned after a game with Pittsfield and nearly set the entire Southend ablaze. As a result, Hartford played all its games on the road until July, when the new steel grandstands were re-built. Also in ’27, Bransfield “loaned” his star third sacker to the Waterbury Brasscos (Tommy Comiskey) after being a hold-out for Jimmy Clarkin’s Senators. When Clarkin tried to get Comiskey back, Waterbury claimed to have him until August and Clarkin went to the EL office to get his player back. The league backed Waterbury’s claim on Comiskey that left a big hole in the Hartford infield. Meanwhile, second baseman Arthur Butler, the team captain, broke his finger on a bad throw by Keesey early in May and Gonzalez was brought in to take his place.”