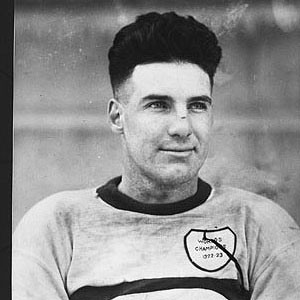

Babe Dye

When thinking of multi-sport athletes from Toronto, the first name to come to mind is likely Lionel Conacher. Conacher was voted Canada’s top athlete of the first half of the 20th century, and excelled in hockey, baseball, and football. He also played lacrosse, wrestled, and boxed. However, another versatile athlete was unjustly lost in his shadow — Cecil “Babe” Dye was superior to Conacher at both hockey and baseball. As a high-scoring right wing, he played in 11 seasons in the National Hockey League from 1919 through 1931, and entered the Hockey Hall of Fame. As an outfielder, he played in the minors from 1920 through 1926, mostly in the International League.

When thinking of multi-sport athletes from Toronto, the first name to come to mind is likely Lionel Conacher. Conacher was voted Canada’s top athlete of the first half of the 20th century, and excelled in hockey, baseball, and football. He also played lacrosse, wrestled, and boxed. However, another versatile athlete was unjustly lost in his shadow — Cecil “Babe” Dye was superior to Conacher at both hockey and baseball. As a high-scoring right wing, he played in 11 seasons in the National Hockey League from 1919 through 1931, and entered the Hockey Hall of Fame. As an outfielder, he played in the minors from 1920 through 1926, mostly in the International League.

Cecil Henry Dye was born on May 13, 1898 in Hamilton, Ontario. His parents were John Sydney Alex Dye and Esther Swinbourne.1 John, who was better known as Sydney, was a lithographer, while Esther was the homemaker. Young Dye unfortunately never got to know his father, since Sydney died when Cecil was only a year old. After the loss of her husband, Esther packed up and moved her family of two to Toronto, where Dye grew up.

Dye went to Jesse Ketchum School when he was a child.2 He first played sports in that school’s playground. His mother helped him with his athletics by building him an ice rink in their back yard.3 When Dye was asked about his mother, he said, “She can throw a baseball harder than I can.”4 If this is true, then it appears that Dye got his athleticism from her.

Dye got his start in organized sports in 1916 when he played with the Toronto Aura Lee amateur hockey team.5 There he scored an amazing 31 goals in eight games during the 1916-17 season.6 At this time, Dye was also playing amateur baseball for the Hillcrest baseball club of the Western City league, where he played for five seasons.7 He was a star pitcher and hard-hitting outfielder. Furthermore, he played halfback for the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Rugby Union. Around this time Dye received the nickname “Babe” by his hockey teammates for his baseball prowess. It was high praise to be likened to the up and coming baseball star, Babe Ruth.

Dye’s bid to play in Organized Baseball was delayed in May 1918 by World War 1. He enlisted in the 69th Battery, Canadian Field Artillery.8 Since it was so late in the war, he never made it overseas. While training at a camp in Petawawa, Ontario, Dye had time to join the battery’s baseball team, which won the title of artillery champions of Canada. They got to play against the Hillcrests, who were senior amateur champions of Canada.9 A one-game playoff took place on October 12, 1918, for the chance to play for the Ontario Championship. Dye started the game for the soldiers. It was tied 1-1 after the fourth inning, but that would be as close to victory as Dye got. The Hillcrests won 8-3, pounding Dye for 11 hits. A few months later, in December, Dye was discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force and his sporting career could resume.10

In April 1919 there were rumors that Dye had signed with the Hamilton baseball team of the Michigan-Ontario League.11 Manager Frank Shaughnessy claimed that he had signed Dye, even though the ballplayer denied it.12 These rumours ended up being false, and the claims were eventually dropped.13 Instead, Dye continued to play amateur baseball through 1919 until October, when he was suspended indefinitely by the Toronto Amateur Baseball Association.14 Dye was caught pitching five games for the Listowel team in the North Wellington league without a permit.15 He was unaware that he needed a permit to play baseball outside of Toronto once the city’s baseball season had ended. Even though he pleaded that he received no money for pitching those games, he was still banned from playing amateur sports in Ontario.

Without any choice, Dye tried to make a go in professional sports. Fortunately, his two best sports, hockey and baseball, did not interfere with each other, so he could continue to play both. First, he joined the Toronto St. Pats of the National Hockey League for the 1919-1920 season, where he emerged as a scoring threat. Despite his rather small size (5-feet-8, 150 pounds) and limited speed as a skater, Dye cemented his reputation as having the hardest shot in hockey.

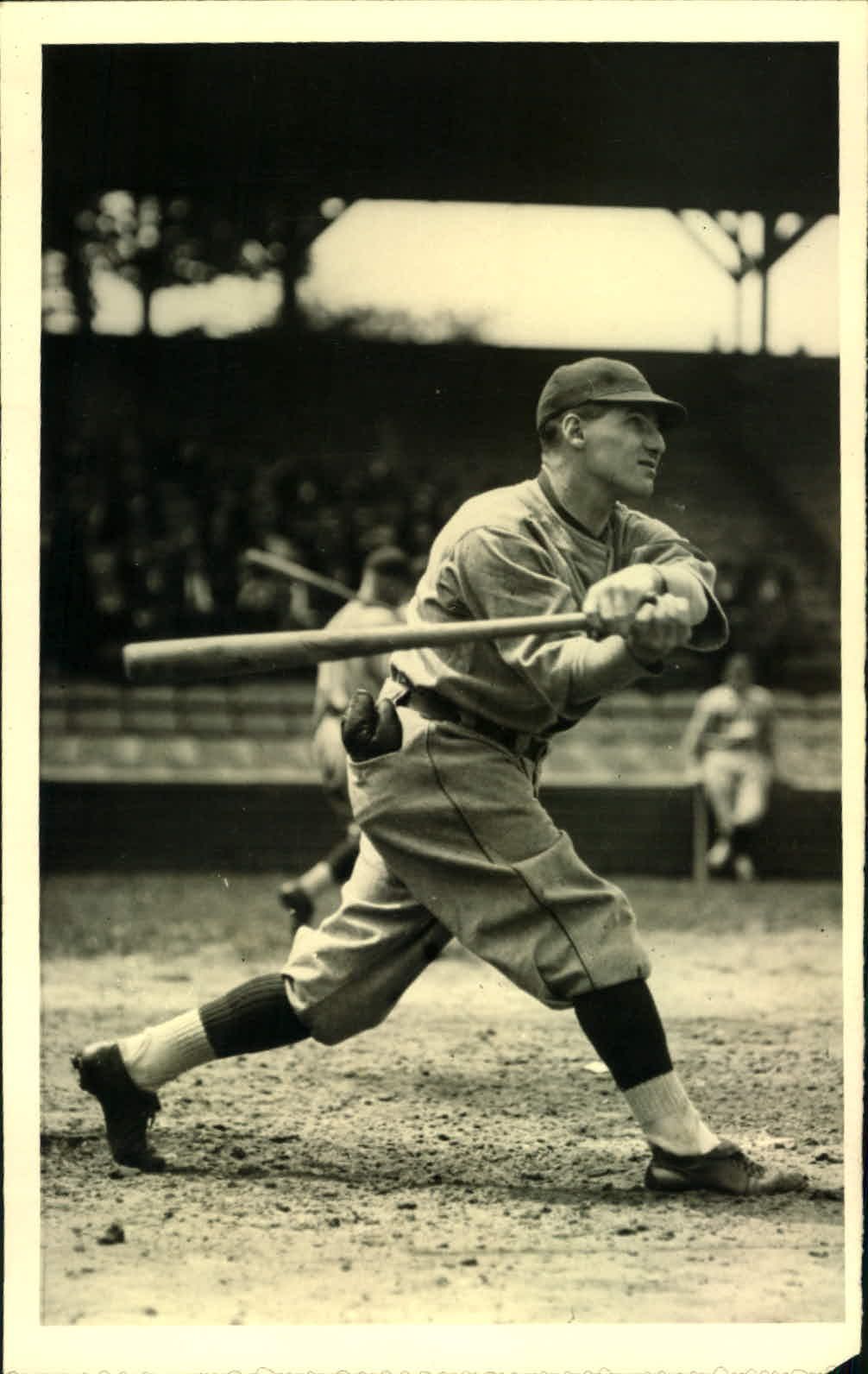

In February 1920 Dye’s professional baseball career began as well. He signed a contract with the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League. He went south with the Leafs for spring training but did not make the team. With nowhere to play, he was loaned to the Syracuse ballclub for a few games.16 He was then returned to the Leafs in late May, but still did not stick. Dye was given his unconditional release a week later.17

After playing in the sandlots for a while, Dye was signed by Knotty Lee, the manager for the Brantford Red Sox of the short-lived Michigan-Ontario league. According to the Winnipeg Tribune, Lee “came to Toronto looking for a fly chaser. Dye was recommended to him as the best prospect in the city by the official scorer of the City Amateur league, and the next day Dye entrained for Brantford.”18 Dye was impressive in the 75 games he played, hitting .327.

Dye had a wonderful sophomore season in the pro baseball ranks. He hit .351, which placed him fifth among batters who appeared in at least 75 games, and his team finished a respectable second in the league. Dye did struggle defensively, though, committing 12 outfield errors. This did not stop him from being described by the Ottawa Citizen as “the best outfielder in the Michigan-Ontario League.”19

Soon after the 1921 baseball season had ended, Dye reaped the benefits of his outstanding season. He was sold to the Buffalo Bisons in the International League for the “highest price ever paid for a Brantford player since the Michigan-Ontario League was founded.”20 Apparently, the Boston Red Sox held an option for Dye but chose not to exercise it, and Buffalo was the next best option. Now Dye was going to play in one of the highest minor leagues in America.

Before Dye could report to Buffalo, he had some important hockey business to take care of. His Toronto St. Pats had beaten the Ottawa Senators for the right to play for the magnificent Stanley Cup. Their opponents were the Vancouver Millionaires. The finals went the distance, but Toronto ended up winning the fifth and deciding game 5-1. Dye made some history by tying the record for most goals in a Stanley Cup Final series with nine. After his historic playoff run Dye arrived at his first spring training with the Bisons a little late.21

By the time Dye returned to baseball, he had received a “handsome increase in salary,” after he returned the first contract that the Bisons sent him.22 He then had to prove that he was worth that money. He got into his first game on April 6, when he played the last two innings in left field in a 5-1 win over Charlotte, going 0-for-1.23 Dye soon won the starting left field job and turned into the player Buffalo hoped he would be.

On May 19 the Bisons visited Toronto, where Dye still lived, to play the Maple Leafs. Dye, who by this time was a hometown hero, received a very warm reception. There was even a band leading a parade on the ferry docks of Hanlan’s Point Stadium. Dye was then given gifts from Mayor Charles Maguire, St. Pats teammates, and the Hillcrests, for whom he had played amateur ball. The fans left somewhat disappointed, though — Dye only went 1-for-4, and the Bisons came from behind to win.24

Although the Bisons finished just third in the IL, Babe Dye had a good first season in Buffalo. He hit a respectable .312 as the full-time left fielder. That completed a jam-packed year in Dye’s career.

By early in the 1923 season, Dye had won a reputation as one of the best ballplayers in the International League. He was described by the Globe as, “master of the swinging bunt, and one of the fastest men in the league in making a gateway for the home plate.”25 He was also “one of the few men in the sport who can place his hits with any degree of consistency.”26

The 1923 season was the best of Dye’s career. He was 25, and in his prime. He led his team with 13 triples, and also smashed 16 home runs, a career high. His .318 average ranked second on the Bisons, who finished fourth, 28 games back of Baltimore’s dynasty, which won seven straight IL pennants from 1919 to 1925. The season was eventful for Dye. On April 29 he was pummeled in the face by Charlie See of the Newark Bears. According to a local Buffalo newspaper, “Dye came in and took part in the relay race. As Dye was about to play the ball on See the latter shot both fists into Dye’s face, damaging Babe’s appearance considerably. See went to earth and Dye hurled the ball at him. See sprawled out and the fight was on. Every player on the grounds, a herd of cops and the first division of the fans got into the melee.”27 Dye also had a 19-game hitting streak which was snapped on August 7. During the streak he hammered 25 hits for a .352 average.28

Near the end of the season rumours were swirling that Dye would be sold to a major league team. Connie Mack offered the Bisons the enormous sum of $25,000 or $30,000 for Dye’s services, but Buffalo refused. There is no definitive reason why Dye did not become a Philadelphia Athletic. It could have been that the Bisons wanted players in return instead of money.29 Alternately, Dye may have wanted to focus on his hockey career.30 The mighty New York Yankees may have also made an offer but were denied the outfielder.31 After all of the rumours around Dye died down, he emerged in the same Bisons uniform.

Dye finished this summer with greater confidence that he was going to eventually make the majors. He held out before the start of the next hockey season. According to the Gazette, he would not play hockey for the St. Pats, “unless he is greeted with a substantial increase in his present salary.”32 That same article reported that Dye’s reasoning was “that in view of his prospects in baseball he cannot afford to take a chance with injuries at hockey.”33 Eventually Dye signed with the Toronto team, but he clearly believed that a career in major league baseball may have been looming.

Dye’s 1924 season was very similar to his previous one. He hit .311 with 10 home runs and a career-high 43 doubles. His Bisons finished third, way behind the Orioles. While Babe Ruth was crushing homers at a record-breaking rate in New York, Canada’s Babe was stuck one rung below the “Big Show.”

Dye’s big-league hopes began to dwindle in 1925. His batting average dipped to .293, and his power disappeared. The Bisons also dropped in the standings to fourth under their new manager, Bill Webb. After leading the NHL in goal scoring the previous season with 38 — the fourth time he was tops in this category — Dye’s scoring touch also seemed to leave him. His goal total sank more than 50%, to just 18.

Toronto’s IL baseball team clearly still thought Dye had some value. They signed Dye in January 1926.34 He led off and played centerfield for the Leafs on opening day and went 2 for 5.35 The season-opening game was played in their new stadium at the foot of Bathurst Street. However, a back injury that Dye had suffered playing hockey affected his baseball play considerably.36 Toronto would eventually dethrone the Orioles as league champs, but Dye would not last that long.

He was released by the Leafs in July.37 The injury-plagued Orioles picked him up quickly thereafter.38 In one of his first games with his new team, he collided with second baseman Heinie Scheer on a pop-up, and Dye had to go to the hospital to get three stitches.39 It is hard to tell if this impaired his play, but he was released by Baltimore after a doubleheader on August 29.40 After the rapid decline in his play, this ended Babe Dye’s professional baseball career.

Dye took a bit of a break from baseball before he joined the Toronto Oslers partway through the 1927 season. The Oslers were a powerhouse on the Toronto amateur and semi-pro baseball scene. He roamed the outfield for the Oslers until the end of the 1928 season, when he retired from baseball for good.41

By this time, Dye’s hockey career was also winding down. His last good season ended in 1927. He then broke his leg and was never the same again. He did not play in the 1929-30 NHL season, and though he came back for six games in 1930-31, he scored just one goal in his last three seasons. He played for three different NHL teams in that time, as well as briefly in the minors.

Even though his talent had diminished, Dye was still unwilling to give up sports. He began his coaching career in 1931 with the senior league Port Colborne Sailors of the Ontario Hockey Association.42 The Sailors finished fourth in the regular season standings but made it all the way to the finals where they lost to Hamilton.43 As a rookie coach, Dye impressed the Chicago team of the American Hockey Association. They hired him to lead them during their sophomore season.44 Dye did not disappoint. He guided the Shamrocks all the way to the finals, which they won. Unfortunately for Dye, he was not there to celebrate with his team. The Shamrocks’ president, Tom Shaughnessy, “censured Dye…on the eve of the championship game.”45 Dye was fired because he let captain Gordan Brydson leave the team to get married. According to the Dunkirk Evening Observer, Dye said, “Shaughnessy asked me if I knew Brydson was going to leave…. I told him I knew it, and he promptly said I was fired. There was nothing I could do about Brydson. He was determined to go in spite of anything I said.”46 Press agent Chester Grant was fired for the same reason, and Bryson was fined $1,000.47

Dye was not out of a job long. He was signed by the rival St. Louis Flyers for the 1932-33 season. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Dye was chosen, “because of his ability to develop youngsters and produce the sensational type of high scoring sextets.”48 One incident on December 26, 1932 described Dye’s short stint with the Flyers very well. He was arguing with referee Cameron McKinnon over a penalty called against St. Louis and “struck the official in the face. McKinnon then banished Dye and fined him $75.”49 He was fired a couple months later, in mid-February.50 The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the morale of the team was low, and his firing by president Harry Taber, “was for the best interests of the club.”51 Babe Dye’s coaching career was done.

Dye continued in hockey as a referee. He worked in a few minor leagues until he was hired by the NHL. He made his debut on March 19, 1935 as an end-of-season replacement.52 In October, he was hired for the next season.53 As a referee, Dye was not liked by the fans. According to an article in the Daily News in 1937, Dye, as well as a couple of other referees, had, “heard the crowd chant ‘two blind mice’ more than any of the others this year.”54 Even if the fans were unhappy with him, Dye stuck around in the NHL until the end of the 1938-39 season. He continued to referee in other leagues until 1943.

After Dye’s sports career ended, he settled down in Chicago with his wife, Isabelle. He worked in the fuel oil business until his death. By then he was superintendent for Seneca Petroleum Co.55

Dye suffered a heart attack on September 19, 1961.56 He was under treatment for a heart ailment until he succumbed to a fatal stroke on January 3, 1962 in Chicago.57 Dye was buried at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.58 He was survived by Isabelle (obituaries did not mention any children).59

Dye’s legacy as the hardest shooter in the NHL lived on. He was posthumously inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1970.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Louis Cauz and Andrew North for their help with this biography, which was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed most of the newspaper articles on newspapers.com, as well as the historical Globe and Mail newspaper archive on the Ottawa Public Library website. The author also accessed Ancestry.ca, Baseball-Reference.com, Hockey-Reference.com, Wikipedia.org, and the Hockey Hall of Fame Book of Players edited by Steve Cameron.

Notes

1 The last name of Dye’s mother has been spelled many different ways in different sources. The author used the spelling found on ancestry.ca under the Ontario, Canada, Marriages, 1826-1936.

2 Stan Fischler, The Handy Hockey Answer Book (Visible Ink Press, 2016).

3 Ibid.

4 Jim Barber, Toronto Maple Leafs: Stories of Canada’s Legendary Team (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 2013).

5 Alan MacLeod, From Rinks to Regiments: Hockey Hall-of-Famers and the Great War (Victoria: Heritage House Publishing, 2018), 151.

6 Ibid.

7 Billy Kelly, “Before and After,” Buffalo Courier, May 15, 1922: 10.

8 MacLeod, From Rinks to Regiments, 152.

9 “‘Babe’ Dye Failed to Hold Hillcrest,” The Ottawa Journal, October 14, 1918: 14.

10 MacLeod, From Rinks to Regiments, 152.

11 “‘Babe’ Dye Signs With Hamilton,” The Ottawa Citizen, April 21, 1919: 9.

12 “‘Babe’ Dye Is Positive,” The Ottawa Citizen, May 2, 1919: 8.

13 “Shag Cancels Claim for Babe Dye,” The Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan), April 22, 1920: 11.

14 “Another ‘Amateur’ Caught with Goods,” The Ottawa Citizen, October 28, 1919: 9.

15 Ibid.

16 “‘Babe’ Dye Released,” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec), June 5, 1920: 21.

17 Ibid.

18 “Dye Owes Start to Knotty Lee,” The Winnipeg Tribune, January 2, 1924: 11.

19 “Babe Dye Goes to Buffalo,” The Ottawa Citizen, September 15, 1921: 11.

20 Ibid.

21 “April Showers Keep Bisons Off Diamond,” The Buffalo Enquirer, March 31, 1922: 8.

22 “Leafs Release Pitcher Taylor,” The Globe (Toronto, Ontario), February 28, 1922: 14.

23 “Bisons Score Again Over Hobby’s Bees,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, April 6, 1922: 16.

24 “Bisons Put on Great Finish to Beat Leafs,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, May 20, 1922: 15.

25 “Major League Clubs Seek Dye’s Services,” The Globe (Toronto, Ontario), May 23, 1923: 10.

26 Ibid.

27 “See Shot Both his Fists into Babe Dye’s Face,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express. April 29, 1923: 44.

28 “Merkle Regains Lead in Batting,” The Globe (Toronto, Ontario), August 11, 1923: 10.

29 “Philadelphia Scout Watching ‘Babe’ Dye,” The Globe (Toronto, Ontario), September 8, 1923: 8.

30 “Tributes for Babe Dye; Former Hockey Great,” Nanaimo Daily News, January 4, 1962: 11.

31 “White Sox Make Offer for Big Bill Kelly,” The Buffalo Enquirer, August 31, 1923: 7.

32 “‘Babe’ Dye Holds Out,” The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec), November 14, 1923: 16.

33 Ibid.

34 “Outfielder ‘Babe’ Dye Signs Toronto Contract,” The Globe (Toronto, Ontario), January 29, 1926: 9.

35 Louis Cauz, Baseball’s back in town (Toronto: Controlled Media Corporation, 1977), 75.

36 Leo Doyle, “Orioles Maintain Advantage With Just A Makeshift Team,” The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), July 27, 1926: 22.

37 “Leafs Release Cecil ‘Babe’ Dye,” The Ottawa Citizen, July 12, 1926: 10.

38 “Glimpse this New Bird,” The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), July 15, 1926: 34.

39 “Orioles Anticipate Stern Games in Syracuse Series,” The Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), July 19, 1926: 17.

40 “Orioles Break Syracuse Jinx,” The Baltimore Sun, August 29, 1926: 17.

41 Kevin Plummer. “Historicist: Going Pro.” Torontoist. https://torontoist.com/2014/04/historicist-going-pro/ (accessed January 30, 2019).

42 “Babe Dye, Star Forward, Named Shamrock Pilot,” Chicago Tribune, September 13, 1931: 30.

43 Fandom. “1930-31 OHA Senior Season.” Ice Hockey Wiki. https://icehockey.fandom.com/wiki/1930-31_OHA_Senior_Season (accessed January 30, 2019).

44 “Babe Dye, Star Forward, Named Shamrock Pilot,” Chicago Tribune, September 13, 1931: 30.

45 “Defeat Duluth, 4-3; Prelesnik’s Shot Triumphs,” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1932: 21.

46 “Chicago Shamrocks American League Champions by 4-3 Win,” Dunkirk Evening Observer, April 9, 1932: 13.

47 Ibid.

48 “‘Babe’ Dye will Pilot St. Louis Hockey Team in Pennant Race,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 16, 1932: 58.

49 “Flyers Lose to Pla-Mors, 2-1; Dye Fined for Hitting Referee,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 27, 1932: 16.

50 W. J McGoogan, “Coach Dye of Flyers Fired; Al Hughes to Direct Team Tonight,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 19, 1933: 39.

51 Ibid.

52 The Ottawa Citizen, March 20, 1935: 11.

53 “Noble and Lalonde On Referee Board,” The Ottawa Journal, October 22, 1935: 21.

54 Gene Ward, “Rangers Abused! Refs Penalize ’Em,” Daily News (New York, New York), December 21, 1937: 57. Note: at that time there were only two officials on ice.

55 “Dye, Ex-Hawk Star, is Dead,” Chicago Tribune, January 4, 1962: 65.

56 “Dye, Ex-Black Hawk Star, in Oxygen Tent,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1961: 69.

57 “Dye, Ex-Hawk Star, is Dead,” Chicago Tribune, January 4, 1962: 65.

58 “Cecil Henry “Babe” Dye.” Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6840478/cecil-henry-dye

59 “Dye, Ex-Hawk Star, is Dead,” Chicago Tribune, January 4, 1962: 65.

Full Name

Cecil Henry Dye

Born

May 13, 1897 at Hamilton, Ontario (Canada)

Died

January 3, 1962 at Chicago, Illinois (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.