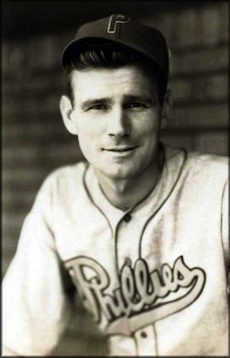

Pete Sivess

On a cold, rainy Valentine’s Day in 1962, several newspaper reporters brazenly walked through the open driveway gates of a mansion on Maryland’s Eastern Shore looking for the United States spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers. Powers, who had been shot down over Russia in 1960, had been recently returned to the U.S. in a prisoner exchange and the press had figured out that he was being debriefed at the mansion.

On a cold, rainy Valentine’s Day in 1962, several newspaper reporters brazenly walked through the open driveway gates of a mansion on Maryland’s Eastern Shore looking for the United States spy-plane pilot Francis Gary Powers. Powers, who had been shot down over Russia in 1960, had been recently returned to the U.S. in a prisoner exchange and the press had figured out that he was being debriefed at the mansion.

As they strode down the driveway, they were stopped by a tall, gruff man who told them that Powers was no longer there. When they asked his name, he told them “Peter Sivess” and said he “worked for the government.” The name meant nothing to the reporters.1

But at one time, that name appeared fairly regularly in newspapers. He, in fact, was former Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Pete Sivess. Only now Sivess worked for the Central Intelligence Agency. During the height of the Cold War, Sivess ran a “first haven” on Maryland’s Eastern Shore where defectors were sent to be debriefed. U-2 spy-plane pilot Powers, after spending 21 months in a Russian prison, was even sent to Sivess’s mansion along the Choptank River after the prisoner exchange brought him back to the U.S.

While Moe Berg may be the most famous major leaguer associated with the CIA, his career as a spy pales in comparison with his ballplaying contemporary Sivess, who worked for the CIA for 24 years and is credited with defining CIA policy for handling Eastern Bloc defectors. Sivess, like Berg, was brilliant and multilingual. But while Berg, after his spying duties during World War II, worked very little for the CIA, Sivess carved out a second career that carried him into retirement.2

Peter Sivess was born on September 23, 1913, in South River, New Jersey, a community about 35 miles southwest of New York City. He was the third of six children born to Lithuanian immigrants Andrew and Alexandra (Naviska) Sivess. The parents spoke no English, and Russian was the main language in the household.3

South River was populated by Eastern European immigrants, especially from Poland, Russia, and Hungary. The children of South River were called Bricktowners because of the brick factory that employed many of the immigrants. Andrew Sivess, however, worked in nearby Milltown as a laborer at the Michelin tire factory.4

Pete not only became a great student but also flourished as an athlete at South River High School. He played football (a teammate was future Pro Football Hall of Famer Alex Wojciechowicz), and was the center on the basketball team. But it was in baseball that he really shined.5

Because he was tall (6-feet-3 with size 14 feet) and possessed a live arm, he dominated high-school batters. In his junior year he threw a no-hitter. He pitched even better in his senior year, at one point having struck out 32 in 20 innings of work. He was named All-State after the 1932 high-school season and pitched for the semipro town team, Janesburg, in the Interboro League during the summer.6

Sivess lettered in four sports at Dickinson College, a private liberal-arts college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He was an end on the football team; played center on the basketball team; and occasionally threw the shot on the track team. But it was as a pitcher on the baseball team that he had his greatest success. By the end of his senior year, in 1936, Sivess had set the college record for strikeouts in a career with 243. In his senior year he went 8-3 with two saves and an ERA of 1.90. “I could throw pretty hard,” said Sivess in a 1988 interview, “and I had a big, roundhouse curve. It came in from third base.”7

Even before Sivess pitched in his senior season, Patsy O’Rourke, a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies, signed him to a contract on February 27, 1936, during the Dickinson basketball season. The plan was that Sivess would report to the Phillies the day after he graduated.8

When Sivess reported after earning his bachelor of philosophy degree, the Phillies were so impressed with him that they placed him on the major-league roster. Sivess saw his first major-league action on June 13 when he pitched the bottom of the eighth in a 7-1 loss at St. Louis. He walked one but gave up no hits or runs. He was credited with his first win on July 14 at Cincinnati when he pitched the eighth and ninth innings in a 9-8 win. On July 21 he banged out his first hit, off Pittsburgh pitcher Bill Swift in a 17-6 loss. Sivess’s first major-league start came on August 12 against the Boston Braves, a game he lost, 4-2. And on September 23 he was the losing pitcher in Game 16 of Carl Hubbell‘s incredible 24-game winning streak.9

Sivess finished the season with a 3-4 record and a 4.57 ERA for the last-place, 100-loss Phillies. The Phillies liked what they saw of the 6-foot-3, 195-pound right-hander. He had a blazing fastball with a “good curve” and a changeup. At times, like most young fastballing pitchers, he was wild. But his fastball was overshadowed by his personality.10

Within weeks of his debut in the majors, Sivess was being called the “next Dizzy Dean” in the press. He was described as a “colorful young right-hander” who has “all the eccentricities that makes Dean the colorful, popular twirler he is.”11

After the Pittsburgh Pirates beat Sivess up for eight runs in 2? innings in July of 1936, he was quoted as saying, “Those guys were sure lucky today. If I’d had my stuff they wouldn’t have made a foul.” He also took to calling himself the “Lion of Leningrad.” However, his teammates starting calling him by his college nickname, “The Mad Russian.”12

The Phillies saw enough positive in Sivess that they invited him to spring training in Winter Haven, Florida, for the 1937 season. After a few days, Sivess wasn’t impressed with the Phillies’ everyday players. “From the looks of this club, I think I’ll quit pitching and try for another position,” he said. “I’d be a cinch to make good from the looks of some of these bums.”13

As it turned out, Sivess had trouble making the club as a pitcher. He had developed a sore arm, which the club attributed to his offseason job as a stevedore for the DuPont Company on the docks of South River. He spent the winter moving heavy goods. At one point, as he moved a crate, he felt something pop in his shoulder. It was so bad that during spring training he was having trouble getting the ball up to the plate.14

Sivess took it in stride. “That’s the value of a college education,” he quipped. “My job was pushing barrels around.” However, the press speculated that he may have permanently ruined his pitching arm. But when the club criticized him for doing heavy work in the offseason, a sportswriter wrote, he “explained that he had to live. Nobody had an answer to that.”15

Despite his sore arm, the Phillies kept Sivess on the roster to start the season. But after appearing in four games with an ERA of 16.88, on May 17 the Phillies optioned him to the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association.

Being sent down didn’t tame Sivess’s personality. He sent a telegram to a Philadelphia sportswriter that read, “Please wire Milwaukee papers full sketch of Pete Sivess and send pictures.” The telegram was signed, “Pete Sivess.”16

Sivess didn’t spend much time in Milwaukee. He got into two games before the Brewers gave up on him, sending him back to the Phillies just ten days after he had been sent down.17

Next the Phillies optioned Sivess to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League. The move saved his career. At Baltimore he came under the tutelage of manager Buck Crouse, who changed Sivess’s delivery from overhead to sidearm. His new “unorthodox delivery” produced tremendous results.18

Sivess went 15-5 for Baltimore with a 2.43 ERA, second in the league among pitchers with more than 100 innings. He pitched nine complete games and saved six games in relief. With a little more support, he might have closed in on 20 wins. Four of his five defeats were by one run. The other loss was by two runs. In fact, seven of his victories were by a margin of one run. He pitched two shutouts.19

“(Sivess) is a combination of Babe Ruth and Carl Hubbell when it comes to ability,” gushed Baltimore business manager Johnny Ogden. “But he’s as eccentric as he is talented. He has the long hair of a monk, the ascetic features of a Gandhi, and the arms of an ape.”20

Sivess’s pitching helped the Orioles into the 1937 International League playoffs, where they were beaten by the Newark Bears. As soon as the Orioles’ season ended, Sivess was called back to the Phillies. He started two games, going 1-1 with a 1.80 ERA. His win was a complete game against the New York Giants on September 30 at the Baker Bowl.

But instead of keeping Sivess as a starter, the Phillies used him out of the bullpen to start the 1938 season. Sivess struggled in that role. Johnny Ogden, the Orioles’ business manager, noticed and inquired in May into the availability of Sivess. But Phillies manager Jimmie Wilson liked Sivess even though he was struggling. “There’s a young right-hander who is going places,” said Wilson.21

Finally, on May 22, Wilson started Sivess and he came through with a complete-game win. But six days later, in his next start, Sivess was shelled and was sent back to the pen. He started only started six more times that season. On October 2, 1938, Wilson called on Sivess to relieve Claude Passeau in the seventh inning against the Brooklyn Dodgers. With the Phils trailing by one run, Sivess gave up seven hits and three runs in two innings of work. It was the last time he pitched in the major leagues. He ended the season with a 3-6 mark and a 5.51 ERA.22

In February 1939 Sivess signed with the Phillies and went to spring training in New Braunfels, Texas. But in April the Phillies sent Sivess and $25,000 to the Newark Bears for first baseman Len Gabrielson.23

At Newark Sivess found himself vying for the fourth spot in the rotation. It didn’t go well, and after he had pitched three games he was returned to the Phillies in late May. On June 1 the Baltimore Orioles conditionally purchased Sivess, hoping he would regain his 1937 form. Sivess complained of a sore arm but it was “reported to be coming around in good shape.” But by June 21, after he had pitched in six games, the Orioles had seen enough and returned him to the Phillies. The Phillies in turn unconditionally released Sivess on June 27. He eventually landed with Jersey City of the International League for the rest of the season.24

Jimmie Wilson, his former Phillies manager and now a bench coach for the Cincinnati Reds, persuaded the Reds to sign Sivess for the 1940 season. But Sivess didn’t make the team and was farmed to Indianapolis of the American Association. Pitching the entire season for the Indians, he went 7-12 with a 4.89 ERA. After the season was over, on November 21, he married schoolteacher Eleanor Katherine “Ellie” Siegel in Spotswood, New Jersey.25

Sivess started in Indianapolis in 1941 but an 0-2 start with an 8.44 ERA in six games brought his release. Elmira of the Eastern League picked him up but he lasted only until late June. The league rival Springfield Nationals grabbed Sivess but by early September they also released him unconditionally. He was out of Organized Baseball for good. For the rest of 1941, he caught on with the powerful semipro team, the Brooklyn Bushwicks (who actually played in the borough of Queens, not Brooklyn).26

In 1942, with the US at war, Sivess went to work at Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. on Long Island, New York. He played for the Grumman baseball team, the Grumman Bombers. His teammates included former major-league pitcher Jumbo Brown, future Washington Senator Bill Zinser, House of David pitcher Moose Swaney, and minor leaguer Fred Doenig. Needless to say, the team was a power in semipro baseball circles in the New York area.27

The following year Sivess took a step back from playing for the Bombers. He did pitch a few games but also appeared in the outfield as well. He was “content to stay in the background,” according to the Brooklyn Eagle. In late August 1943, Sivess left Grumman, joined the Navy, attended officers’ training school, and was commissioned as an ensign at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Former major leaguers were often offered the chance to play baseball during the war but Sivess declined. “I went in to get the job done,” said Sivess. “There was a war on, and wearing a baseball uniform was the last thing I wanted to do.”28

Sivess’s time with the Navy prepared him for his eventual career with the CIA. He was assigned to the chief of naval operations helping train the Russian Navy. When World War II ended he was in Cold Bay, Alaska taking part in preparations for a sea assault on Japan. After the war, he became the acting naval attaché to the Allied Patrol Commission in Constanta, Romania. His group’s task was to run Romania until the country’s government could get back on its feet. He also worked in Czechoslovakia and, for his efforts, received the Military Order of Merit First Class from Czechoslovakia.29

In 1948 Sivess joined the CIA, a year after it was founded. Shortly after that, on January 21, 1949, Sivess’s son, George Peter was born. He was the only child for Sivess and his wife, Ellie.30

In 1951, after Sivess had became the CIA’s chief of the Alien Branch, he persuaded the agency to purchase a 26-room mansion in Royal Oak, Maryland, that could be used as a “first haven” for Soviet Bloc defectors. Built in 1928, the mansion, named Ashford Farms, sat on 60-plus acres near the confluence of the Choptank River and Chesapeake Bay. Ellie and Pete made their home in Cheverly, Maryland, but Pete would often travel back and forth depending on who was being housed at Ashford Farms.31

Probably the highest-profile spy Sivess handled was “notorious double agent” Nicholas Shadrin. Sivess and Shadrin eventually became good friends, hunting and fishing on Ashford Farms and vacationing together with their wives. Sivess’s friendship with Shadrin ended when Shadrin went missing on a trip to Austria in 1975, never to be heard from again.32

In 1965 the Sivess name was associated with baseball again when Pete’s younger brother Andy was hired as a trainer for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League. Andy was an excellent athlete in his own right, having been a three-sport star for Rutgers University in the mid-1940s.33

Sivess retired from the CIA in 1972 and moved to St. Michaels, not far from the site of the CIA mansion. In 1973, Sivess was inducted into the Dickinson College Sports Hall of Fame. Ellie and Pete eventually moved to an assisted living facility in North Carolina. On May 12, 2001, Ellie died. Two years later, on June 1, 2003, Pete died at a health-care facility in Candler, North Carolina, a town outside of Asheville. He is buried in the cemetery of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Spotswood, New Jersey, the same church he was married in. He was survived by his son, George, a West Point graduate.34

In 1984 Sivess granted John Steadman of the Baltimore News-American an interview. While he would not talk about his time in the CIA, he opened up about his baseball career. “I always thought I was every bit as good as the players I was facing,” said Sivess. “But I honestly wasn’t enamored with baseball. That’s just the way I am.

“The game was just a phase of my life.”35

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions of Ray Nemec, for his help with Sivess’s minor-league statistics, and Jim Gerenscser, Dickinson College archivist and fellow Dickinson alumnus, for his help with Sivess’ time at the college.

Notes

1 Bridgeport (Connecticut) Telegram, February 15, 1962.

2 Ronald Kessler, Escape From The CIA (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 122-123.

3 San Diego Evening Tribune, September 12, 1936.

4 Richard Whittingham, What a Game They Played (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 155.

5 Whittingham, What A Game They Played, 155; Trenton Evening Times, February 20, 1932.

6 Trenton Evening Times, April 29, August 13 and August 27, 1932; Press release in Sivess’s Hall of Fame file.

7 Wilbur J. Gobrecht, The History Of Football At Dickinson College: 1885-1969 (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania: Kerr Printing Co., 1971), 207-208, 226, 233; Gettysburg Times, May 11, 1936; Rich Westcott, “Pete Sivess: He Was NOT Just Another Ballplayer,” Phillies Report, May 12, 1988, 10-11; Wilbur J. Gobrecht, 125 Years of Dickinson Baseball History (Carlisle, Pennsylvania: s.n., 1993), 68. According to Sivess, his involvement with the track and field team started when, after his baseball game was rained out, to kill time, he went over to the track meet and talked the coach into letting him throw the shot. He took first place in the event.

8 Press release and transaction sheet in Sivess’s Hall of Fame file; Rich Westcott, “Pete Sivess,” Phillies Report, May 12, 1988, 10-11.

9 New York Post, June 8, 1936.

10 New York Post, June 2, 1938; San Diego Evening Tribune, September 12, 1936.

11 The Sporting News, November 25, 1937; San Diego Evening Tribune, September 12, 1936.

12 San Diego Evening Tribune, September 12, 1936; The Sporting News, November 25, 1937; Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, September 22, 1937; Woodbridge (New Jersey) Leader-Journal, April 15, 1938.

13 Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, March 9, 1937; Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1937.

14 Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1937; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 26, 1937; Springfield (Massachusetts) Daily Republican, March 23, 1937.

15 Charleston (South Carolina) Gazette, March 28, 1937; Chester (Pennsylvania) Times, April 6, 1937.

16 The Sporting News, July 22, 1937.

17 Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Northwestern, May 26, 1937.

18 Transaction sheet in Sivess’ Hall of Fame file; Frederick (Maryland) Post, August 28, 1937; Eugene Murdock, Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game, 1920-1940 (Westport, CT: Meckler Publishing, 1991), 74-75; Baldwinsville (New York) Gazette and Farmers’ Journal, March 31, 1938.

19 The Sporting News, December 30, 1937; Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, September 22, 1937; Breakdown of 1937 IL season in Sivess’ Hall of Fame file.

20 Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, September 22, 1937.

21 Syracuse (New York) Herald, May 2, 1938; New York Post, June 2, 1938.

22 Arizona Republic, October 3, 1938.

23 Dallas Morning News, February 5, February 27, 1939; Syracuse (New York) Herald, April 9, 1939;

24 The Sporting News, May 11, June 1, June 8, June 15, 1939; transaction sheet in Sivess’ Hall of Fame file

25 San Antonio Express, February 27, 1940; Trenton Evening Times, November 24, 1940; Rich Westcott, “Pete Sivess: He Was NOT Just Another Ballplayer” Phillies Report, May 12, 1988, p. 10-11.

26 Corning (New York) Evening Leader, May 26, 1941; Springfield (Massachusetts) Daily Republican, July 1, September 5, 1941; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 9, 1941.

27 Long Island Star Journal, June 1, 1942; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 15, 1942.

28 Long Island Star Journal, June 30, 1943; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 20, June 25, August 18, 1943; The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Rich Westcott, “Pete Sivess: He Was NOT Just Another Ballplayer” Phillies Report, May 12, 1988, p. 10-11.

29 The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Rich Westcott, “Pete Sivess: He Was NOT Just Another Ballplayer” Phillies Report, May 12, 1988, p. 10-11.

30 The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Ronald Kessler, Escape From The CIA (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 123.

31 The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Washington Post, August 26, 1981; Ronald Kessler, Escape From The CIA (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 123-124; Henry Hurt, Shadrin: The Spy Who Never Came Back (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981), 77.

32 The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Henry Hurt, Shadrin: The Spy Who Never Came Back (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981), 170.

33 The Sporting News, July 17, 1965.

34 Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, June 3, 2003; The Sporting News, January 9, 1984; Washington Post, August 26, 1981.

35 The Sporting News, January 9, 1984.

Full Name

Peter Sivess

Born

September 23, 1913 at South River, NJ (USA)

Died

June 1, 2003 at Candler, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.