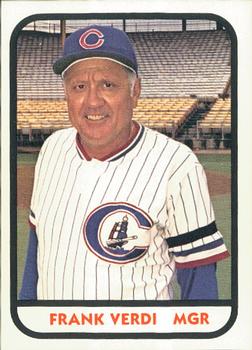

Frank Verdi

Frank Verdi accumulated 1,832 hits across 18 seasons playing minor-league baseball (1946-63) — but appeared in just one major-league contest. He played a single inning at shortstop for the Yankees in 1953 and never got to bat.

Frank Verdi accumulated 1,832 hits across 18 seasons playing minor-league baseball (1946-63) — but appeared in just one major-league contest. He played a single inning at shortstop for the Yankees in 1953 and never got to bat.

Verdi is perhaps most remembered for his 24 years of managing in the minor leagues and independent ball, in 12 different cities, over a period spanning 1961 to 1995. His teams included players such as Thurman Munson and Don Mattingly. His minor-league achievements earned him induction into the International League Hall of Fame.

Figuratively speaking, Verdi gave his life to baseball. He almost did literally as well, taking a bullet to the head during a 1959 game in Havana, Cuba.

Frank Michael Verdi was born on June 2, 1926, in Brooklyn, New York. His childhood spanned the years of the Great Depression. He grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, at that time a nighborhood composed mostly of Jewish and Italian immigrants and African Americans. His Italian family had three generations living in the same brownstone. Frank had one older brother named Joseph. Their father, Michael, was a butcher, and Frank made deliveries for him riding his bicycle.1 The boys’ mother was Aida (née Spizuoco), known familiarly as “Edy.”

As of the 1940 census, the Verdi family (without the elder generation) was living at 1508 President Street in Crown Heights, a mile or so east of where Ebbets Field then stood. Frank and his friends used to station themselves outside the ballpark to battle for real baseballs that were hit onto the street during batting practice.2 At least as late as 1953, 1508 President was still listed as Frank’s address in a Brooklyn Eagle article.3

Verdi attended Brooklyn Boys High School, where he played basketball, soccer, and baseball. On the basketball court, he finished third in the league in scoring in his senior year.4 The right-hander played third base, shortstop, and center field for the baseball team. He graduated in 1944 and shortly thereafter enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He played shortstop for the base team and tried his hand at boxing while stationed at Camp Shelton in Virginia. His skills on the diamond may have kept him from being sent overseas to fight in the war.5

In 1946, after his military service, Verdi enrolled at New York University on a basketball scholarship.6 Years later, a fellow NYU basketball recruit would say that Frank was talented enough to have played professionally.7 He was also very talented on the baseball diamond, however, and was lured away from college when offered a contract with the New York Yankees during his first semester.8 Paul Krichell, the scout who had previously signed Lou Gehrig and Phil Rizzuto, persuaded Verdi to sign a contract for $200 per month. Whether the Dodgers-Yankees rivalry entered Frank’s feelings is not known — but he had realized his dream of becoming a pro ballplayer.9

The 5-foot-10, 170-pound infielder spent his first three seasons bouncing around the lower levels of the minors, at that time Classes B, C, and D. In his first year of pro ball, Verdi developed a friendship with a teammate named Edward Ford, who would go on to become better known by his nickname of “Whitey.” A few years later, in Binghamton, New York, Ford introduced Verdi to an “athletic and beautiful” 18-year-old named Pauline Pasquale when Ford was dating Pauline’s sister.10 Frank and Pauline married on February 3, 1951.11

From 1949 to 1952, Verdi spent most of each season in Binghamton, one of the Yankees’ Class A affiliates. In 1950 and ’52, he hit over .300. His hustle, versatility on defense, and ability to pull off the “hidden ball trick” on opponents made him a popular player for Binghamton. The team hosted a “Frank Verdi Night” in 1951 in which he was presented with a “nice hunk of cash from the Sons of Italy and his teammates.”12

After spending 1953 spring training with the Yankees, Verdi had a status of “pending future assignment.”13 At that time, teams could carry extra players until having to trim the roster to 25 on May 15. Verdi remained with the Yankees for home games but did not travel on road trips in April, and it was not clear to reporters if he was even on the roster.14

On Sunday. May 10, 1953, the Yankees were playing the Red Sox at Fenway Park. In the sixth inning, Joe Collins pinch hit for Rizzuto, the Yankee shortstop and leadoff man. Manager Casey Stengel called Verdi’s name, and the rookie entered the game at shortstop in the bottom of the sixth. The Red Sox were retired in order without a ball hit Verdi’s way. In the seventh inning, with two outs, six straight Yankees reached base and three runs were in with the Bronx Bombers taking a 5-3 lead. With the bases loaded, Verdi was due up. As he stepped into the batter’s box, the Red Sox made a pitching change, replacing Ellis Kinder with Ken Holcombe. Stengel countered the move by replacing Verdi with another rookie, Bill Renna, who had knocked 28 home runs in the minor leagues the year before. Just like that, Verdi’s major league career was over. He was assigned to Triple-A Syracuse two days later when rosters had to be trimmed.

Verdi spent the rest of the 1953 season in Syracuse, hitting .270 with an OPS of .689. His fiery nature on the field was evident on multiple occasions, including a couple of incidents that made the newspapers. He received a $25 fine and three-game suspension for throwing a ball at and bumping an umpire.15 He was also involved in a home plate collision that left the opposing catcher with “a fractured cheekbone and loss of teeth.”16 His season ultimately ended in late August after he was involved in another collision at the plate and injured his ankle. The Yankees went on to win the World Series in 1953. For his inning of play, Verdi received a partial World Series share of $500, a hundred dollars more than the batboys.17

Verdi spent the rest of the 1953 season in Syracuse, hitting .270 with an OPS of .689. His fiery nature on the field was evident on multiple occasions, including a couple of incidents that made the newspapers. He received a $25 fine and three-game suspension for throwing a ball at and bumping an umpire.15 He was also involved in a home plate collision that left the opposing catcher with “a fractured cheekbone and loss of teeth.”16 His season ultimately ended in late August after he was involved in another collision at the plate and injured his ankle. The Yankees went on to win the World Series in 1953. For his inning of play, Verdi received a partial World Series share of $500, a hundred dollars more than the batboys.17

For the next three years, Verdi played for Kansas City, Columbus, and Tulsa, mostly at second and third base. In 1955, while with Columbus (a Kansas City A’s affiliate), he was named player of the month for June, receiving a $100 wristwatch for the honor.18 He played hard and was not afraid of confrontation. On July 8 of that season, he was involved in a wild game versus Toronto in which there were multiple brawls involving Toronto first baseman Lou Limmer. The incidents culminated in a donnybrook in which Verdi “leaped on Limmer’s back and then connected with a right to the jaw.”19 It took “11 sheriff’s deputies, seven local policemen, and umpires” to break up the melee.20 During a playoff game between Tulsa and Houston in 1956, a brawl broke out between the two teams, and an AP photo shows Verdi in the middle of the fracas.

In the spring of 1957, Verdi’s contract was purchased by the Rochester Red Wings, then the Triple-A affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals. Verdi spent three seasons manning third base for Rochester. He made the International League All-Star team in 1957, a season in which he hit .284 with a .359 OBP.

It was during his tenure with Rochester that Verdi was involved one of the wildest events ever to take place on a professional baseball field. In late July 1959, the Red Wings were in Havana, Cuba, to play the Sugar Kings, then a member of the International League. The game of Friday, July 24, was preceded by a two-inning exhibition in which Fidel Castro’s “Bearded Rebels” played against a team of military police.

On July 25, the Red Wings and Sugar Kings finished a suspended game from earlier in the year, and then the regularly scheduled game went to extra innings. At midnight, with the game tied in the 10th inning, the stadium went dark and a spotlight highlighted the Cuban flag in center field as the national anthem was played to commemorate July 26, the anniversary of the Cuban revolution. Then approximately 40 to 50 soldiers in the stadium began shooting guns in the air to celebrate the occasion.21 Verdi recalled the scene in 1999: “Bullets were falling out of the sky everywhere. We didn’t know what the hell was happening.”22

Play eventually resumed after things settled down and the gunfire ceased. In the 11th inning, Rochester manager Cot Deal was ejected for arguing that a Havana player missed first base on his way to a double. Deal’s heated argument and ejection fired up the crowd, some of whom resumed firing their guns. Verdi, who was not active on the roster following a beaning a few weeks prior, assumed managing duties and took the field to coach third base as the game went to the top of the 12th. While standing in the coaching box, Verdi took a stray .45 caliber bullet to the head, knocking him to the ground. As luck would have it, he was wearing a plastic insert inside his hat, then an alternative to wearing a batting helmet. Verdi credited this insert with saving his life. “If that bullet had been two inches to the left, the boys on the ballclub would have had to chip in $5 apiece for flowers,” said Verdi after the incident.23

Another player, Havana shortstop Leo Cardenas, was grazed on the shoulder by a bullet around the same time. At this point, the umpires called the game, and it went in the books as a 4-4 tie. The following season, with political tensions rising, the Sugar Kings relocated to Jersey City.

After spending the 1960 season with Charleston in the American Association, Verdi was named a player-coach for Syracuse in 1961. Syracuse had a dismal record of 22-52 when their manager, Gene Verble, turned in his resignation. Verdi took over as manager, and the team had a record of 34-46 the rest of the way with him at the helm. He remained as Syracuse’s manager in 1962. In May, with his shortstop injured during a six-game losing streak, the 35-year-old skipper came out of retirement and inserted himself in the lineup at shortstop.24 In his first at-bat in almost a year, he tripled. However, Syracuse continued to struggle, and on July 12, he was replaced as manager by Johnny Vander Meer, a move suggested by Verdi himself.25 Verdi remained with Syracuse as a coach and then had another short stint as a player after being purchased by the Yankees to fortify their Double-A team in Amarillo, Texas.

Verdi’s last handful of games as a player came in the 1963 season while managing the Greensboro Yankees, a Single-A team in the Carolina League. Greensboro won the pennant that year with a record of 85-59. During his minor league career, which spanned 18 seasons, Verdi accumulated 1,832 hits in 6,776 at bats for a batting average of .270. He hit 48 home runs and walked more times than he struck out.

Verdi managed in the Yankees farm system for the next seven seasons, with stops in Fort Lauderdale, Toledo, Oneonta, and Binghamton before returning to Syracuse midway through the 1968 season. With Binghamton and Syracuse, he managed Munson, a young first-round draft pick. When Verdi’s son, Frank Jr., asked about the catcher with a less-than-impressive physique, the manager said that it was just a matter of time before Munson was playing in Yankee Stadium.26 His assessment proved accurate.

Wherever Verdi managed, the whole family was involved. In Syracuse, Pauline played the organ and their four sons (Michael, Frank Jr., Paul, and Christopher) served as bat boys, scoreboard operators, and members of the grounds crew.27 Mike went on to manage for several seasons during the 1980s and ’90s in the minors and indie ball. Pauline’s support no doubt played a role in Verdi’s successful career, and her legendary cooking became well known to players, writers, and friends over the years. “What these wives put up with…I take my hat off to them,” said Frank Jr. in a 2020 interview.

Verdi guided Syracuse to International League pennants in 1969 and 1970. In the latter, Syracuse defeated Omaha in the Junior World Series, and he earned the league’s Manager of the Year award. Sportswriter Dick Young noted in The Sporting News in October 1970 that “if some club in the majors is looking for a man with a Vince Lombardi-style of discipline that players seem to appreciate, Frank Verdi is their man.”28

Coming off two successful seasons with Syracuse and several in the lower levels of the minors, Verdi felt he deserved a job in the big leagues or at least a raise in pay. After neither came to fruition, he sat out the 1971 season and worked as a steamfitter in New York before being laid off that summer.29 “I’ve been in this game 27 years and I don’t have five cents to show for it. This is why you have to fight for a raise sometimes,” he said.30 That winter, Verdi managed Ponce in the Puerto Rican Winter League, a position he had also held in previous winters, and his team won the Caribbean Series. In 1972, he returned to the managerial seat with Syracuse. “What you do,” he said at the time, “is do your job and pray for a break.”31

Verdi managed only one of the next four summers: in 1974, when he piloted the Astros’ Triple-A team in Denver. He spent a couple of years in between working security at Aqueduct and Saratoga racetracks. He also worked on construction of the World Trade Center (as did at least one other former big leaguer, Carl Furillo, whose account was documented in The Boys of Summer).32

In 1977, Verdi received an offer to skipper another International League team: the Tidewater Tides, a Mets affiliate. Not a fan of the Mets organization, he was hesitant to take the job but acquiesced at his wife’s urging.33 With the Tides, he managed several players who would have success in the big leagues, including Mike Scott, Wally Backman, Hubie Brooks, and Mookie Wilson.

By then in his early fifties, Verdi maintained his fiery competitiveness. During a game versus Charleston in 1979 in which he argued with the home plate umpire about the strike zone, he was grazed by a ball he thought was thrown at him by the opposing dugout. “Verdi removed his jacket, cap, and spectacles, and charged Charleston’s bench” before umpires and players from both teams restrained him.34

Author J. David Herman described Verdi’s feelings about umpires: “He could respect an ump who reached a certain standard, but very few did in his eyes. Even mentioning the profession could make Verdi cross. To hear him tell, their incompetence threatened his livelihood. He resented them. He had years of practice doing so.”35 Mike Bruhert, a pitcher on Verdi’s Tidewater teams, recalled that he would turn his hat backwards so he could get as close to the umpire as possible without making contact. Bruhert compared his tirades to those of Earl Weaver.36

In 2020, Bruhert recalled a meeting that took place with the Tidewater pitching staff. One relief pitcher wanted to know his role with the team. “I tell you what,” said Verdi, “if you pitch well in the sixth inning, you’re my seventh-inning man, and if you pitch well in the seventh, you’re my eighth-inning man, and if you pitch well in the eighth, you’re my ninth-inning man.”37

Verdi was fired by the Mets after the 1980 season in what the Tidewater GM called “an organizational decision.”38 It was later reported that Mets farm director Dick Gernert had campaigned for Verdi’s dismissal.39

Verdi returned to the Yankees organization in 1981, this time managing their Triple-A team in Columbus, Ohio. The Clippers were coming off back-to-back International League championships. The big-budget Yankees invested heavily in their minor league system, and owner George Steinbrenner expected his affiliates to be successful. Columbus was loaded with up and coming players such as Dave Righetti, Steve Balboni, and Andre Robertson, as well as talented players, such as Marshall Brant, who were blocked on the depth chart by a successful Yankee roster.

Herman chronicled the 1981 Columbus Clippers season in his book Almost Yankees: The Summer of ’81 and the Greatest Baseball Team You’ve Never Heard Of. Though Verdi still occasionally lost his temper, he had mellowed out some by this point. Herman told the story of Verdi’s reaction when loud music was playing in the clubhouse during an early-season losing streak. Rather than berate the team, he broke out into an awkward dance which loosened up the clubhouse. The team’s fortunes turned around quickly thereafter. Herman also described how Verdi sometimes eased tension in the dugout by “having a few sips of wine — or something stronger — during games.”40 There was also the time in 1981 when Verdi got together with old friends Ford, Mickey Mantle, and Yogi Berra, among others. Ford choked on a chili bean and couldn’t breathe. Verdi calmly punched his friend in the chest, dislodging the bean and likely saving Ford’s life.41

When Major League Baseball players went on strike for nearly two months in the middle of the 1981 season, several of the Clippers’ games were broadcast on national television. The team finished with a record of 88-51 and won a third straight International League championship.

Marshall Brant was a player with a lot of experience playing for Verdi, spending two years in Tidewater and then two more seasons in Columbus under the veteran manager. In 2020, Brant recalled that his first two years playing for Verdi were difficult because the manager was “continuously tinkering” with his swing.42 Brant was purchased by the Yankees in 1980 and assigned to Columbus, where he played under a different manager and had a dedicated hitting coach, Brant had a breakout season and won the International League’s Most Valuable Player Award. When reporters asked him about his turnaround, Brant recalls that “as polite as I could, I threw some jabs at Frank.” When Verdi got the Columbus job in 1981, the two were reunited, and Brant’s experience was better the second time around. “I give him credit. He said, ‘Hey Marsh, just do what you feel comfortable with.’ From that point, I grew to like him and felt more relaxed.”43

“He always wanted a shot to manage or coach in the big leagues. He was just jinxed for whatever reason. Maybe he rubbed some people the wrong way. He was not always politically correct,” assessed Brant.44

“Frank was tough but had a big heart. He was one of a kind.” said Bruhert, who also played for Verdi’s Columbus teams, enjoyed many afternoon card games with the skipper, and kept in touch long after his playing career. “If you played hard, you played, and if you didn’t play hard, you didn’t play.”45 This philosophy did not always align with front office preferences for playing time to be distributed based on draft position or salary rather than effort or merit.

The 1982 Columbus squad featured Mattingly, a 21-year-old first baseman. The team finished in second place despite poor pitching and a constant churning of the roster. At the end of the year, Verdi was fired. The Clippers’ general manager, George Sisler Jr., explained Verdi’s ousting: “From a Columbus standpoint, Frank was great. He did everything we wanted him to. Evidently, New York felt there were other areas of managerial duties that Frank was deficient in.”46 It was reported that Verdi had not filed some game reports on time and didn’t have infield practice the last two weeks of the season. However, Verdi himself was not given any reason for his firing.47 He later learned from Yankee scout Birdie Tebbetts that Steinbrenner was poised to promote him to a big-league coaching role until Clyde King, who had butted heads with Verdi decades earlier, spoke up and inaccurately criticized some of his managerial decisions.48 With that input, Steinbrenner changed his mind and fired Verdi.

After spending the 1983 season managing the San Jose Bees in the Class-A California League, Verdi took the helm as manager of Rochester. The IL team for which he had played in the ’50s had become a Baltimore Orioles affiliate in 1961. In 1984, the Red Wings limped to a 52-88 record, and after the team got off to an 18-40 start in 1985, Verdi was let go. As Greg Boeck pointed out in Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle, Verdi was a victim of a poor Baltimore farm system.49 Whitey Ford went to bat for his old friend, urging Steinbrenner to rehire him, and the Yankee owner agreed to bring him back as a scout.50

Before that, however, there was a brief and odd interlude. Ahead of the 1986 season, San Jose — which featured numerous substance-abuse reclamation projects such as Steve Howe, Mike Norris, and Ken Reitz — named Verdi manager. Even before Opening Day, however, Frank resigned to take the scouting job. He recommended that his son Mike become the club’s skipper, and the younger Verdi did get the job later that bizarre season.51

Verdi spent three seasons as an assistant coach at Saint Leo College in Florida in the early 1990s. He remained out of professional baseball until 1993, when at age 67 he was hired by the Sioux Falls Canaries of the independent Northern League for their inaugural season. “I have spent a lot of time telling people retirement is not all it’s cracked up to be. I’m glad to be back at work,” he said at the time.52 Mike Verdi was a coach for Sioux City, another Northern League team. “There are not too many men who endure 14-hour bus rides — but he’s a real trooper,” said team owner Harry Stavrenos.53 The Sioux Falls roster included former major leaguers Pedro Guerrero and Carl Nichols. When asked about his experience playing for the veteran manager, Nichols recalled in 2020 that Verdi “was very no-nonsense but was always teaching.”54

During the 1994 season, Verdi was hospitalized twice with chest pain. His second visit included a stress test that showed signs of heart disease.55 He underwent quadruple-bypass heart surgery on July 29 and announced he planned to take the remainder of the season off.56 Stavrenos took over as manager in his absence. Players remarked that Verdi’s leadership would be missed. “He knows how to deal with all the little things that come up, whether it’s something that happens in a game or during the course of a season,” said Mike Burton, the Canaries first baseman.57 After five weeks, Verdi’s recovery was going well and he returned to manage the last three games of the season.

Verdi came back to Sioux Falls in 1995 but was removed from the manager’s position after just nine games. He accepted a role as hitting instructor. Stavrenos expressed concerns over his health as the reason for his demotion, though Verdi disagreed. “There’s nothing wrong with my health. But it’s his money, it’s his ballclub.”58 By the end of the year, Verdi’s tone was more caustic: “If you want to know the truth, [Stavrenos] cut my legs out from under me. Who’s gonna hire a 69-year-old man that people say is sick.”59 On September 19, Verdi filed charges against Stavrenos, claiming his demotion was in violation of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission dismissed the charges.60 This was Verdi’s last job managing in professional sports.

Fifty years had passed between Verdi’s first season playing in 1946 to his last days managing in 1995. In addition to his dozen stops managing in the minor leagues, he managed winter league teams in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and the Dominican Republic. He won Puerto Rican championships with Ponce in the 1971-72 season and with Mayagüez in 1983-84.

When no job was available, Verdi spent off-seasons in such odd jobs as bartender, postal worker, and used-car salesman.61 To show for his years in the game, he received a minor league pension of $142.60 per month (the pension program was not established until he was well into his managing career).62

Verdi spent his reluctant retirement in New Port Richey, Florida, where he helped coach local high school kids. He returned to the Independent Atlantic League as a pitching coach with Newark in 2002. Newark had advanced to the league championship series when manager Marv Foley was suspended for his involvement in a brawl. Verdi managed the team in his place, and the team captured the league title in his last game wearing a uniform. Verdi was inducted into the Syracuse Baseball Wall of Fame in 1999, the Binghamton Baseball Shrine in 2004, and the International League Hall of Fame in 2008.

In his Florida home, Verdi had a display case with numerous mementoes from his years in baseball. He also kept a notebook full of stories he wrote in retirement. Although Verdi had only the briefest of major league careers, according to Frank Jr., his father “considered himself blessed that he could do what he loved. . .He loved the thinking part of the game. He knew the game inside and out. Billy Martin once said that it was a sin that he didn’t get to manage in the big leagues.”63

“There’s no doubt in my mind I could’ve managed in the big leagues, no doubt in a lot of people’s minds. But that’s life,” Verdi said in 2004.64

Frank Verdi passed away on July 9, 2010, at the age of 84. He is buried at Grace Memorial Gardens in Hudson, Florida.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Marshall Brant, Mike Bruhert, and Frank Verdi Jr. for sharing their memories and stories.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 J. David Herman. Almost Yankees: The Summer of ’81 and the Greatest Baseball Team You’ve Never Heard Of (University of Nebraska Press, 2019): 64

2 Herman, 64.

3 “Brooklyn Rookie Signs Yank Pact,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 7, 1953: 7.

4 John W. Fox. “Hustle Keeps Verdi Perched on 2nd Base,” Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, NY), April 16, 1950: 54.

5 Herman, 65.

6 Telephone interview between Frank Verdi Jr. and the author, July 31, 2020.

7 Frank Verdi Jr. interview.

8 Fox, “Hustle Keeps Verdi Perched on 2nd Base.”

9 Herman, 66.

10 Herman, 67.

11 Pauline Pasquale Verdi’s obituary: https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/pressconnects/obituary.aspx?n=pauline-pasquale-verdi&pid=165584115, accessed June 25, 2020.

12 Charley Peet. “Kline’s Hit Earns No. 10 for Schneib,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, September 1, 1951: 10.

13 John W. Fox. “Opening Day Win Recalls ’52 Starter,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, April 23, 1953: 24.

14 “Ex-Card Hurler Employs 2-Platoon Catching System,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, May 11, 1953: 14.

15 George Beahon. “Walker, Wings’ Pilot, Suspended for Three Days,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1953: 32.

16 Paul Pickney. “In the Pink,” Democrat and Chronicle, August 23, 1953: 51.

17 “Ex-Triplets Net 50Gs in Series,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, October 8, 1953: 25.

18 The Sporting News, July 15, 1955: 44.

19 “Limmer Floored 3 Times in Donnybrook,” Democrat and Chronicle, July 9, 1955: 16.

20 “Jets, Leafs Exchange Blows During Minor League Game,” The Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction, CO), July 9, 1955: 4.

21 Jimmy Burns. “Int Will Play Out Havana Sked, Despite Shooting, Shag Decides,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1959: 9.

22 Bill Madden. “Orioles’ Cuba Trip Opens Old Wounds,” Daily News, March 28, 1999: 92.

23 Burns.

24 “Skipper Verdi to Chiefs’ Rescue,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1962: 33.

25 “Vandy Returns to Class D Park for Bow as Chief Pilot,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1962: 43.

26 Frank Verdi Jr. interview.

27 Herman, 161.

28 Dick Young. “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, October 10, 1970: 16.

29 George McClelland. “Syracuse Pilot Frank Verdi — Winners Sometimes Wait,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1972: 30.

30 McClelland.

31 McClelland.

32 Frank Verdi Jr. interview.

33 John W. Fox. “Verdi Still on Deck,” Press and Sun-Bulletin, May 24, 1981: 15.

34 “Volatile Verdi,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979: 48.

35 Herman, 145.

36 Telephone interview between Mike Bruhert and the author, July 28, 2020.

37 Bruhert interview.

38 Sandy Schwartz, “Caught on the Fly: Mets Release Verdi,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1980: 37.

39 Fox, “Verdi Still on Deck.”

40 Herman, 14.

41 Herman, 12.

42 Telephone interview between Marshall Brant and the author, June 14, 2020.

43 Brant interview.

44 Brant interview.

45 Bruhert interview.

46 “Yankees Dismiss Verdi as Clipper Manager,” Democrat and Chronicle, October 15, 1982: 33.

47 Greg Boeck. “Forget Rumors; O’s Anxious to Keep Lance,” Democrat and Chronicle, October 20, 1982: 7.

48 Herman. 243-4.

49 Greg Boeck. “Verdi’s Firing Symptomatic of Disarray,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 18, 1985: 28.

50 Herman, 12.

51 Tom Verducci, “Weirdest. Team. Ever: Drug users, has-beens and never-weres on 1986 San Jose Bees,” Sports Illustrated, September 16, 2016.

52 Mick Garry. “Leader of the Flock,” Argus-Leader, June 11, 1993: 19.

53 Mick Garry. “Verdi to Lead Canaries Again in ’94,” Argus-Leader, June 19, 1994: 21.

54 Direct communication between Carl Nichols and the author via twitter.com on June 13, 2020.

55 “Verdi Hospitalized: Chest Pains Sideline 68-Year-Old Manager,” Argus-Leader, July 27, 1994: 21.

56 Mick Garry. “Verdi’s Season is Over,” Argus-Leader, August 4, 1994: 17.

57 Garry. “Verdi’s Season is Over.”

58 Mick Garry. “Verdi Out as Manager, Named Hitting Coach,” Argus-Leader, June 14, 1995: 23.

59 Jim Cheesman. “Verdi Brushes Back Canaries’ Owner,” Argus-Leader, October 1, 1995: 21.

60 “EEOC Dismisses Verdi Complaint vs. Canaries,” Argus-Leader, March 26, 1996: 16.

61 Joey Knight. “A Pitch for Verdi,” The Tampa Tribune, August 2, 2004: 8.

62 Knight.

63 Frank Verdi Jr. interview.

64 Knight.

Full Name

Frank Michael Verdi

Born

June 2, 1926 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

July 9, 2010 at New Port Richey, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.