Fred Hoey

“Eddie Morris, chubby little commodore of the Massachusetts Bay Yachting Association, recently had a Bosch radio receiving set installed in his power cruiser by the Motor Parts Company of 106 Brookline Avenue. Eddie is well pleased with the performance of the set, as it enables him to keep in touch with Fred Hoey at the ball parks while enjoying the cool sea breezes.”1

“Eddie Morris, chubby little commodore of the Massachusetts Bay Yachting Association, recently had a Bosch radio receiving set installed in his power cruiser by the Motor Parts Company of 106 Brookline Avenue. Eddie is well pleased with the performance of the set, as it enables him to keep in touch with Fred Hoey at the ball parks while enjoying the cool sea breezes.”1

The City of Boston was on the move in October of 1897, literally. The new subway system had debuted on September 1, in an attempt to alleviate congestion in the city. “The passengers aboard the car had packed themselves in like sardines” wrote the Boston Globe, “like a jungle of wild animals, dipped down the incline for the underground run to Park St. … How so many persons ever got aboard one car is a mystery.”2

Just a couple of miles away from the busy Park Street stop stood the South End Grounds (or the third version of it), at the intersection of Walpole Street and Columbus Avenue. The grandstand, with its twin spires, would remind you of a mini-Churchill Downs. However, this was no fantasy land as the “passing trains could be counted on to periodically rain smoke and cinders down on the third base patrons and on the field itself. If the wind was right and the traffic heavy, games were halted in order to allow the haze generated by the trains to clear.”3

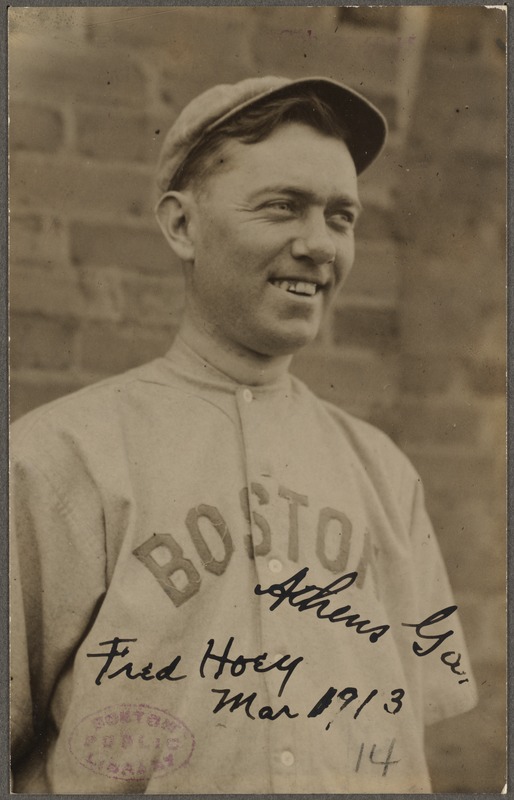

If a modern television camera could have panned the crowd, you would have caught a glimpse of 12-year-old Fred Hoey sitting in the bleachers with his father, watching Frank Selee’s Boston Beaneaters battle the Baltimore Orioles in the 1897 Temple Cup.4 It was Hoey’s first baseball game, and he sat in awe of players like Kid Nichols, Jimmy Collins, Hugh Duffy, John McGraw, and Wee Willie Keeler. Hoey would observe a lot of sports over his life, particularly baseball. While he played on amateur and semipro teams, his career was mostly spent observing the game from behind a typewriter or microphone, becoming a “word painter”5 for his readers and listeners, who depended on his precise but down-to-earth descriptions. From a boy in the stands, to umpire and usher, to newspaperman and announcer, to one of the most heard voices in the country in his day, Fred Hoey was a sports-broadcasting pioneer.

Frederick James Hoey was born in Boston on May 11, 1885,6 to Lawrence A. and Florence M. (Place) Hoey, who also had three other sons, Lloyd, Moses, and Henry. Lawrence Hoey was a first-generation American whose father emigrated from Ireland. He worked as a clothing cutter, and in 1905 worked in the men’s furnishing department at the R.H. White Company department store.7 Florence played the organ at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in Boston’s West End. The church and organ still survive.8 The Hoey family lived at 188 Talbot Avenue in the Dorchester section of Boston, according to the 1900 and 1910 censuses.

As a young man, Fred Hoey not only loved baseball; he was also a prominent figure in the early history of hockey in Boston. His hockey career included stints as a high-school and semipro player, coach, referee, manager, and publicity director. Hoey played integral role in the introduction of hockey in Boston. “During the infancy of indoor hockey in Boston, Fred’s love for the game and his untiring efforts to educate the public to the sport helped materially in gaining hockey recognition,” the Boston Globe reported.9

The Boston Ice Hockey League, consisting of 14 clubs in the Boston area, was formed in 1904, and Hoey was on the league’s executive board.10 Hoey also played baseball for the semipro Lovells team.11 And he was featured in a 1905 issue of the Boston Traveler as the team captain of the Franklin (Massachusetts) A.A. ice-hockey team of the New England Ice Hockey Association. Hoey was praised for his “wonderful ability at following the puck.”12 In 1905 Hoey became the chief usher at the Huntington Avenue Grounds, where the Boston American League team (later called the Red Sox) played.13 Hoey was working for the Boston Journal in 1907, and participated in a Boston Press Golf Club of New England match.14

Hoey moved to the Boston Post a couple of years later, when he became chief scorer of the Boston Doves, later the Braves.15 He reported on the Doves at spring training in Augusta, Georgia.16 On April 7, 1910, Hoey was aboard a train carrying the Doves through Kentucky to play a spring-training game in Louisville when it crashed in the early-morning hours. “Never has a baseball club come so close to death and the players of the Boston team fully realize the danger they faced in a railroad wreck this morning,” Hoey reported.17 The train plowed into some loaded coal cars. Engineer William Rudolph and a six-week-old baby were killed, but the quick actions of Doves catcher Leon “Doc” Martel, a trained physician, saved the life of fireman William Knick. “Dr. Martel is greeted as the man of the hour. The big physician, after one of the hardest days a baseball player ever spent on the road, remained up all night and rendered assistance wherever it was necessary. … The poor fellow could hardly stand,” Hoey wrote.18

Hoey became one of Boston’s first hockey writers and was instrumental in making hockey, a Canadian sport, popular in Boston. In 1910, the Boston Arena (now known as Matthews Arena, the oldest indoor hockey arena still in use as of 2017) was built, bringing hockey indoors for Boston-area players for the first time. “It was like a gift from heaven,” Hoey wrote a few years after the arena was built. “The hope and ambition of every Greater Boston hockey player was realized – players and coaches could now count on a schedule of ice.”19 He also picked an all-scholastic football team from schools in the Boston area.20 In 1912 Hoey wrote several articles for the Boston Journal on local high-school and college hockey games. Space was even devoted to Hoey’s picks for an all-scholastic team. He was also praised by the Boston Journal as one of the best local officials in the area.21 A 1913 advertisement of the Boston Journal praised Hoey as a “Recognized Leader on Athletic Topics.”22

Hoey began writing for the Boston Herald by 1914, mainly covering local school athletics and hockey at all levels of competition. A column he wrote was called “Passing the Puck.” In 1915 Hoey was identified as the publicity director for the Boston Arena, and was also the hockey team manager.23 Hoey’s 1918 draft card listed his employment as a “sporting newspaper writer” for the Boston Herald.

Hoey also covered the Boston Braves and Red Sox as the Herald’s baseball editor. He reported in the Herald on January 18, 1919, that “Babe Ruth, Red Sox ace, wants considerably more salary than he has received in the past, and if his demands are refused he will retire at his farm in Sudbury for a year.”24 Ruth owned a 40-acre farm in Sudbury, Massachusetts, outside Boston, and was threatening to spend the year farming, telling Hoey, “Another thing I assuredly will not do, if I sign, and that is to play first base, left field, and pitch on alternate days. … There will be no more mixing positions for me.”25

The 1920 census lists Hoey as living on Beacon Street in Winthrop, Massachusetts, near Boston. Hoey’s brother Lloyd died in 191626 and Fred lived with two nephews, Lloyd Jr. and John H., as well as his father, Lawrence. Hoey was still officiating games in the 1920s, and a 1922 high-school football game in Manchester, New Hampshire, resulted in a bloodied Hoey after he made an unpopular call against the home team and outraged fans attacked him.27

Hoey was the publicity director for the two Boston hockey teams: the Bruins from 1924 to 1926 and the Tigers from 1926 to 1928, both clubs’ early years. Hoey was also the New England hockey editor of Spalding’s Hockey Guide. 28

Hoey moved on to writing for the Boston American, where he was working when he was hired as a broadcaster.

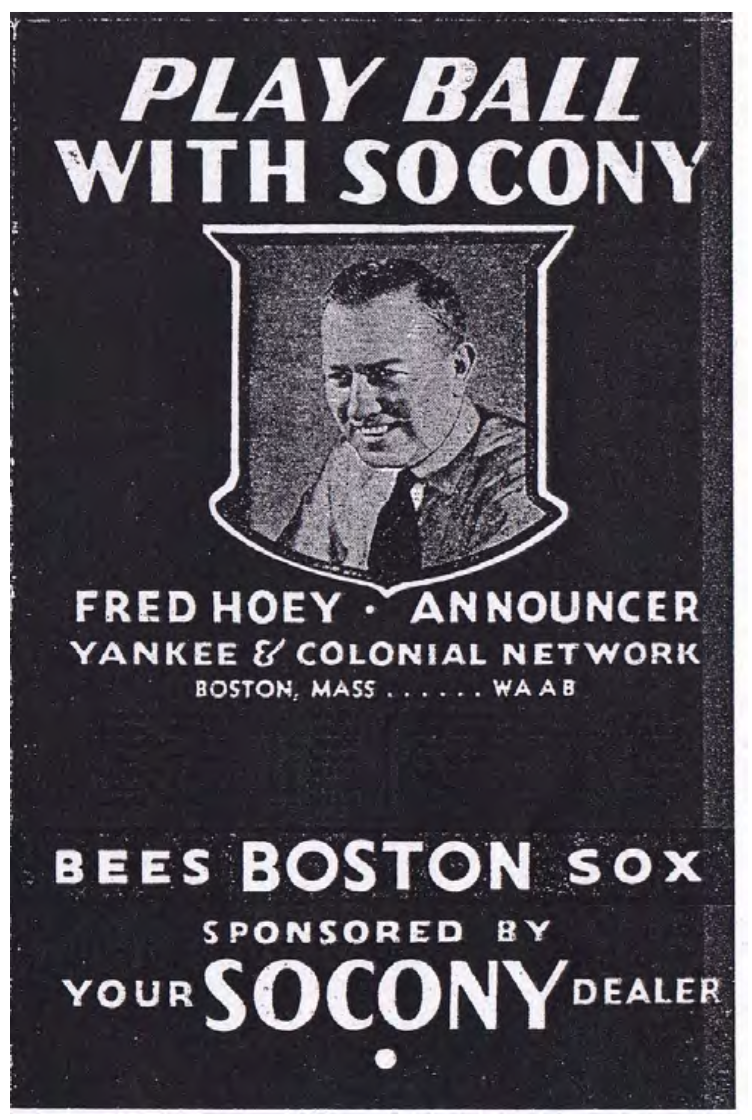

Fred Hoey was not the first announcer to air play-by-play of Boston baseball (in 1926 several local sportswriters, including Gus Rooney and Charlie Donelan, took turns doing the games); but he became the first full-time announcer when he took on that role during the 1927 season.29 A pioneering broadcaster, he began announcing the home games for both the Braves and Red Sox on WNAC radio, and he quickly proved himself up to the task. WNAC was founded in 1922 by John Shepard III, who had inherited family-run department stores in Providence and Boston.30 In the early days there were no sponsors, and only one game of a series was broadcast. So well received were Hoey’s descriptions of the games that by the end of his broadcasting career businesses were competing to run ads on his broadcasts.31 There were no broadcast ratings in Boston yet, but it was obvious from fan mail that Hoey had a lot of listeners. As a result, many of Hoey’s broadcasts during the 1930s had sponsors, including Kentucky Winners cigarettes,32 Socony Oil,33 and Kellogg’s cereals.34

Meanwhile, the local baseball writers were singing Hoey’s praises. “With a background of baseball knowledge and reporting, acquired through many years of study of the sport, Mr. Hoey is fully qualified to give an interesting and accurate story of the games to the listeners,” wrote the Globe.35

“In his vivid account of a game, Fred’s announcements are given in straight baseball language, the language of the fan,” wrote the Herald.36 Hoey was given credit for helping shut-ins “keep a complete and official score of the game following Hoey’s description over WNAC,” and women “find that his thorough explanation of each play and his elimination of technical phrases gives them a better knowledge of the game.”37

But while he had the support of the Boston reporters and the appreciation of the fans, Hoey’s early days behind the microphone were anything but glamorous. “The job was new to us and we experienced the usual nervousness that goes with one’s introduction to the microphone,” Hoey recalled in 1936. “In the pioneer days, we had no private booths in which to work. We were at either end of the press box – wide open – ready to flirt with pneumonia for dear old WNAC.” When not battling the weather, Hoey had to battle the broadcasting of Ted Husing with rival station WBET, who set up a microphone in the center of the press box.38 And where today a team of announcers broadcasts the games, Hoey did them himself, even if there was a doubleheader.39 (By some accounts, this did not change until 1934, when Nate Tufts, an advertising agency executive, began assisting Hoey, as well as filling in when Fred was on vacation.)40 In addition to broadcasting the games, Hoey also hosted his own sports show on WNAC, beginning on May 10, 1928.41 During the baseball season, he interviewed players from the Red Sox and the Braves.

In 1929, when WNAC won exclusive rights to broadcast Red Sox and Braves home games, Hoey was described as “an announcer for baseball who knows his stuff. He needs no coach or pinch hitter. He gives you what you want – baseball.”42 Hoey also broadcast the first Sunday game in Boston history.

The arrangement WNAC made was good news for the fans, who learned that Hoey would “be on the air … this season broadcasting local ball games from both playgrounds.”43 Also in 1929, Hoey was named assistant manager of the Boston Garden.44 He wrote the game program when the Boston Bruins opened the defense of their Stanley Cup championship.45

The 1930 census lists Hoey as living with his sister-in-law Anna (Lloyd’s widow) and nephews Lloyd Jr. and John H. at 195 Water Street in the village of Saxonville, located within the town of Framingham, about 40 miles west of Boston. Hoey’s profession was listed as an “announcer” of “field sports.” (According to Boston Post cartoonist Bob Coyne, the Saxonville address was a farm, and Hoey spent some of his free time there, enjoying the outdoors.46)

In May of 1930, John Shepard III created the Yankee Network, with radio stations throughout New England.47 This increased Hoey’s audience, and he was considered to have the widest following of any broadcaster of his day. In 1930 he spent his days during the winter at a desk at the Boston Garden, working in publicity and advertising.48

On September 8, 1930, Hoey broadcast alongside Boston Post writer Bill Cunningham for an old-timer’s game at Braves Field. The game was also carried by CBS radio, the first such national baseball broadcast to emanate from Boston.49

Hoey’s many fans often sent letters to newspaper editors praising his on-air work. For example, a crabby fan named J.L. Carter of Portland, Maine wrote, “There is one particular pet grouch which I have in connection with the (World) series, and that is the radio broadcasting. We New England fans appreciate the fact that the men who broadcast the games have national reputations, but, so far as baseball is concerned, compared to our own Fred Hoey they are huge jokes. I have listened to him ever since he has been broadcasting ball games, and never have failed to visualize every play so clearly. … Baseball has been developed to a very high degree, and it needs a broadcaster who understands all its fine points and intricacies to satisfy the great army of its followers.”50

Even after only a few seasons, fans began requesting a day to honor Hoey. This letter was sent to Burt Whitman of the Boston Herald in 1930:

My dear Mr. Whitman,

While “days” for baseball players are in vogue, I would like to suggest some sort of a testimonial of appreciation to Fred Hoey for the splendid service he has rendered to baseball and to the thousands of fans who cannot always be at the game. I am sure that great numbers of people would welcome an opportunity to contribute to such a testimonial.

I don’t know how such a thing is started, but I offer the suggestion and I hope I may have the opportunity to contribute.

Sincerely yours,

Palmer York51

Whitman agreed with his reader, saying Hoey “stands head and shoulders above the average run of boys who tell their public through the mike of the goings on out there on the field. He is clear. He has enthusiasm, without silliness. … Hoey utilizes every minute and never gets tiresome. He’s really too good to be true. You never hear a ‘knock’ directed at his blond head.”52

In January of 1931, the Braves’ president, Judge Emil Fuchs, announced plans for a Fred Hoey Day, noting the hundreds of fans who had sent requests. “Stay-ins and shut-ins will have a chance to show their appreciation for Fred’s work …” wrote Whitman in the Herald.53 He added, “From all parts of New England the fans and those who seldom attend games, but often listen to them, are sending in their requests for tickets. Probably some of the outlying fans will not be able to attend, and those who will find themselves up against that obstacle are sending donations. …”54

In January of 1931, the Braves’ president, Judge Emil Fuchs, announced plans for a Fred Hoey Day, noting the hundreds of fans who had sent requests. “Stay-ins and shut-ins will have a chance to show their appreciation for Fred’s work …” wrote Whitman in the Herald.53 He added, “From all parts of New England the fans and those who seldom attend games, but often listen to them, are sending in their requests for tickets. Probably some of the outlying fans will not be able to attend, and those who will find themselves up against that obstacle are sending donations. …”54

A crowd of 30,000 filed into Braves Field on that hot Saturday, June 20, 1931, as the Braves faced the St. Louis Cardinals in a doubleheader. Between games, they honored Hoey with a $3,000 certificate of deposit from the fans, money from the Red Sox and Braves, a wristwatch, gold, a pipe, and even a check from the visiting Cardinals. A box of silk shirts came from Boys of Quincy, and flowers came from relatives. Fans sent gifts of cakes, socks, and neckties, which, considering it was Father’s Day, Whitman concluded that “some of the fans had robbed dad of the things they were planning to give him today.”55

Given how knowledgeable and personable Hoey was, his fans had long been asking why he was never given a chance to broadcast a World Series game on a national network. Both the Braves and the Red Sox recommended him, and even the Boston baseball writers thought it would be a good idea.56 Thus, it was a popular move when Hoey was chosen by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis as the lead play-by-play announcer for Games One and Five of the 1933 World Series,57 to be carried on the Columbia Broadcasting System (today known as CBS). Landis wanted an experienced announcer calling the action, and Hoey was named, along with France Laux, Roger Baker, and Gunnar Wiig.

What would have been Hoey’s career highlight, however, ended disastrously and has forever since been a subject of mystery. Hoey seemed nervous in his Game One play-by-play descriptions on October 3, 1933, and his voice sounded hoarse. Fans on the West Coast complained that Hoey’s words were unrecognizable.58 Between halves of the fourth inning, Hoey asked to be removed, claiming he was suffering the effects of a cold (one he said had been getting steadily worse for several weeks); as a result, he had lost his voice entirely. The plan was for him to recover and be back on the air later in the series; but this never happened. Meanwhile, the Herald reported that its phone operators were “swamped with calls” from fans asking why Hoey was suddenly off the air,59 and the story was front-page news. But while listeners were told he was ill, and many sent him get-well cards,60 rumors were circulating that a rival network had given Hoey excessive amounts of alcohol before the game. The fans might not have realized, but some of his colleagues were aware of Hoey’s struggles with alcohol.61 “Yes, he liked the sauce, or so I’ve heard,” said future Red Sox broadcaster Ken Coleman, who grew up listening to Hoey.62

In an era when the personal lives of broadcasters (and ballplayers) were rarely discussed, people undoubtedly accepted Hoey’s explanation that he had developed a bad cold, and nothing further was said about it. And it did not affect his relationship with the listeners: He remained extremely popular, and fans could not wait to listen to him on the air. “In the majority of cases,” wrote the Globe, “the listener-in gets a better idea of what is going on from Hoey’s description than he would if he were actually at the ball park, for Fred gives a lot of inside stuff that would have gone unnoticed by the ordinary observer.”63

In 1934, one of Hoey’s faithful listeners was Jack Buck, a future winner of the Baseball Hall Fame’s Ford C. Frick Award for broadcasters. Buck, a 10-year-old boy growing up in Holyoke, Massachusetts, was captivated as Hoey’s voice described his hero Jimmie Foxx and the Red Sox. “I listened to Fred Hoey broadcast the games on radio,” Buck reminisced in 1997, “imagining what the Green Monster looked like, painting a picture in my head of the green grass and the players whose names I can still recite to this day.”64

Hoey, like any announcer, was remembered for familiar sayings and slogans. He tended to open a game with a formal greeting, like “Hello everybody, this is Fred Hoey speaking.”65 In one well-remembered on-air gaffe, he announced, “Hello Fred Hoey, this is everybody talking.”66 Hoey would keep a chart in the broadcast booth that listed information on each player. “Nothing that we announce is trusted to memory,” Hoey said. “It is all in typewritten form before us.”67 Thanks to the Yankee Network, and later the expanded Colonial Network, Hoey’s voice was heard by a potential 5 million listeners.68 This also helped him to gain more female fans; his popularity with women was attributed to “the fact that technical phrases are eliminated in his talk on the air.”69 In other words, he was thorough yet understandable, something any fan could appreciate.70

“You can keep well posted on the progress of the Fenway Park game,” wrote Arthur Sampson of the Herald in 1936, “if you happen to be on a shopping tour, for nearly every store, fruit stand, or barber shop has a radio turned on to Fred Hoey’s play by play description, and should you happen to miss an inning or two in your progress you can always get a detailed description from the man or woman behind the counter.”71

But while Hoey’s popularity with the fans remained high in 1936,72 his sponsors were evidently not as thrilled with his on-air persona. Hoey was suddenly fired, a move the sponsors endorsed by claiming, “Hoey failed to keep up a steady line of chatter while games were in progress.”73 The dismissal came as a shock to Hoey; he said, “I was given no indication by either of the sponsors during the season that I was not living up to their expectations. It was not until after the baseball campaign ended that I was told my method on the air allowed for too many pauses during the course of a game.”74

Many fans were outraged, and sent furious letters to the Boston newspapers.75 Even newspaper reporters wrote support for Hoey, a former newspaperman whose job as a radio announcer could be viewed as competition.76 The public outcry helped bring Hoey back to the booth with a new contract, which also included a daily 15-minute radio program recapping the day’s baseball results, sponsored by Kentucky Club Smoking Tobacco.77

Hoey’s renewed career lasted only two seasons, and John Shepard III gave a one-year contract to former player Frankie Frisch. Shepard said Hoey was not renewed for two reasons: “The first is that Hoey asked for an increase which we didn’t believe was justified. The second is we have a new sponsor this year and we believed it was the right time to change our broadcaster.”78

Hoey was taken by surprise. “As far as asking for a raise is concerned I wish to deny this,” he said. “I did ask the network to release me from the after-game broadcast for which I had a separate contract as it was under a different sponsorship. That was the last I heard about the matter.”79 The change in Boston’s baseball announcer, while small in world significance, nevertheless was enough of a story in Boston to land it on the same front page of the Herald that carried the headline, “Hitler in Prague as Conqueror.” Hoey had not even been notified in person, instead learning of his fate through his contacts in the newspaper world. “I haven’t as yet been notified officially of this matter,” Hoey said. “… This leaves me with no plans for the present.”80

Fans once again rallied to defend Hoey, creating a booster club and seeking signatures on a petition to bring him back. This time, however, their efforts were not successful.81 However, Hoey did begin a new 10-minute sports talk show on WBZ, Monday through Saturday at 6:15 P.M., sponsored by Howard Johnson’s Ice Cream. “Because of the tremendous popularity of Hoey among New England radio listeners,” said the Globe, “Mr. Johnson feels he is providing a distinct public service in bringing Fred back to the air.”82

The 1940 census lists Hoey living at 77 Triton Avenue in Winthrop with his 91-year-old father, Lawrence, his sister-in-law Anna Hoey, and his nephew John H. Hoey. He was earning $2,414 a year as a “radio broadcaster.” Hoey worked for the Boston American after leaving his radio career, remaining there until retiring in 1947. He belonged to the Baseball Writers Association of America, the Hockey Writers Association, and the New England Football Officials Association.83 When he wasn’t broadcasting, writing, or officiating, Hoey enjoyed going deep-sea fishing.84

Hoey suffered a stroke in 1949 and remained in poor health for the remainder of his life. On November 17, Richard White, 22, of Winthrop, delivering groceries to Hoey’s home, found him unconscious on the kitchen floor and the house filled with gas fumes from an open jet on the kitchen stove.85 White and neighbors carried Hoey to the front yard. Firefighters attempted to revive him with an inhalator, but were unsuccessful. Hoey was survived by two nephews, John and Lloyd.86 The medical examiner ruled his death accidental, due to asphyxiation.87 A requiem Mass was held at St. John the Evangelist Church in Winthrop,88 and Hoey is buried in Winthrop Cemetery. A memorial plaque was unveiled in the Braves Field press box in his memory.89

“He was generally credited with building up baseball broadcasting to the lofty spot it holds in the American sports scene today,” the Globe wrote of Hoey.90 And one of his loyal Boston listeners still held Hoey in high regard 40 years later. “In those days,” Bill Ahearn of Everett, Massachusetts, wrote in a letter to the Boston Herald Traveler in 1972, “dozens of fans walking the streets of Boston would stop at candy stands and stores that aired the game to listen to Fred Hoey. He was good, believe me.”91

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and checked for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Special thanks to Donna Halper for assistance in writing and researching this article.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author benefited from the following resources:

Ancestry.com.

“Every Fan in New England Knows Voice of Fred Hoey, Yankee Network Announcer,” The Sporting News, articled labeled “2/11/32” in Fred Hoey’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Familysearch.org.

Halper, Donna. “Some John Shepard History,” retrieved April 29, 2015. bostonradio.org/essays/shepard.html.

Fred Hoey file, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

“Hoey on Radio in World Series,” Boston Herald, September 26, 1933: 1.

“Nation’s First Subway Opens in Boston, September 1, 1897.” Mass Moments. Retrieved May 1, 2015. massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=254.

Redmount, Robert Samuel, “The Earliest Radio Accounts of Red Sox Baseball,” and “Fred Hoey – Boston’s Broadcasting Pioneer,” in Red Sox Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishers, 1998), 206.

“South End Grounds.” Sports Temples of Boston. Boston Public Library. Retrieved May 2, 2015. bpl.org/collections/online/sportstemples/temple.php?temple_id=13.

Notes

1 “Kennedy Marine Basin at Squantum to Be One of Best Boat Organizations in Nation,” Boston Herald, August 3, 1930: 25.

2 “First Car Off the Earth,” Boston Globe (Evening Edition), September 1, 1897: 1. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20050829090042/http://members.aol.com/netransit/private/tss/tssnews.html.

3 Bill Felber, A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters, and the Battle for the 1897 Pennant (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 60.

4 “Fred Hoey to Report World Series Games for Radio Fans.” Framingham (Massachusetts) News, September 26, 1933.

5 Edgar G. Brands, “Fred Hoey Moved to the Radio Booth From Usher, Player, Reporter Roles,” The Sporting News, May 7, 1936: 2.

6 Boston city records show Frederick James Hoey’s birth as May 11, 1885, while both of Hoey’s draft cards (World War I and World War II) give inconclusive dates. The WWI draft card gives his birth date as 5/12/1884; the WWII draft card gives the 5/12 date, but appears to have 1884 written over 1885 and above these is written 1883. At the time of death, the Boston Herald, Boston Traveler, and New York Times gave his age as 64 (born 1885) while other reports such as the Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts) and Portland (Maine) Press Herald, gave his age as 65 (1884). The Boston Globe reported both ages in two separate reports.

7 On the front page of the September 25, 1905, Boston Globe, Lawrence Hoey is mentioned for giving testimony to the Boston police about a suspect in a murder case who had entered the R.H. White store. The victim was Susan A. Geary and the case became known as the “Boston Suitcase Murder.”

8 “Mrs. Florence Hoey,” Boston Herald, August 9, 1916: 7; http://stjosephboston.com/about-the-parish/history/.

9 “Fred Hoey to Help Manage Garden,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1929: 25.

10 “With 14 Clubs, New England Hockey League Formed,” Boston Globe, December 10, 1904: 12.

11 “Neversweats Want to Play,” Boston Herald, April 21, 1902: 4.

12 Boston Traveler, January 3, 1905.

13 “First Baseball Game Saturday,” Boston Herald, April 7, 1929: 38.

14 “Trenchant Pen to Yield to Cleek,” Boston Herald, July 15, 1907: 9.

15 “Fred Hoey Dies From Gas Fumes,” Portland Press Herald, November 18, 1949: 1; “First Baseball Game Saturday.”

16 “With the ‘Doves’ in Their Spring Training Camp at Augusta,” Boston Journal, March 14, 1910: 11.

17 Fred J. Hoey, “Martel Lauded as Train Wreck Hero,” Boston Journal, April 8, 1910: 11, 1.

18 Ibid. See also “Doves Shaken Up in Wreck,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1910: 5; “Engineer Killed,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1910: 5; “Doves Come out of Wreck Unhurt,” Boston Herald, April 8, 1910: 6.

19 Jeff Z. Klein, “The Ice Rink That Changed Boston Hockey,” New York Times, December 29, 2009 [online edition]. Retrieved April 29, 2015, http://nytimes.com/2009/12/30/sports/hockey/30arena.html. The exact source and date of the original Hoey quote are unknown to the author.

20 Boston Journal, December 4, 1911, and December 2, 1912, are two articles the author discovered.

21 “Bob Dunbar’s Sporting Chat,” Boston Journal, November 29, 1912: 10.

22 Boston Journal, April 5, 1913.

23 Carleton Manager of Arena Seven: Fred Hoey to Supervise Game at Local Rink,” Boston Journal, November 8, 1916: 10; Editor & Publisher (Vol. 48) in 1915 lists Hoey in this position, but the author does not know exactly when he started at the Boston Arena.

24 Fred Hoey, “Babe Ruth Threatens to Strike if Demand for Big Salary Raise Is Refused,” Boston Herald, January 18, 1919:14.

25 Ibid.

26 “Dies Suddenly in Bridgeport,” Boston Post, November 8, 1916: 74.

27 “Fred Hoey Beaten Up By Angry Grid Crowd,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, November 5, 1922: 1.

28 “Fred Hoey to Help Manage Garden,”

29 When he was fired in 1939, the Boston Herald reported that Hoey had been on the job 13 years, which would give him a starting year of 1926; the Boston Globe reported that his career spanned 12 years. WNAC had broadcast a few Braves games in 1925, with Charles Donelan and Ben Alexander as the announcers. The Red Sox’ first broadcast was Opening Day, April 13, 1926, with Gus Rooney doing the announcing, and Rooney also broadcast the Braves’ home opener on April 21. The author did not find Hoey’s name found in any newspaper report as a broadcaster until 1927. However, often announcers were not listed.

30 WNAC became the modern-day WRKO station. The Shepard Department Store was founded in 1865 by John Shepard Sr. John Shepard III believed hosting a radio station in the store would draw customers who wanted to see the live broadcast, and perhaps pick up a few items while they were there. See Donna L. Halper, Boston Radio: 1920-2010 (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishers, 2011), 15.

31 “Fred Hoey Dies From Gas Fumes.”

32 Display ad for Kentucky Winners cigarettes, Boston Globe, September 12, 1934: 6.

33 Display ad for Wheaties and Socony sponsorship of baseball, Boston Globe, April 22, 1936: 23.

34 “To Sponsor Broadcasts.” Boston Globe, January 8, 1938: 4.

35 “WNAC Will Broadcast Braves, Red Sox Games,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1929: 15.

36 “First Baseball Game Saturday.”

37 Ibid.

38 Brands. Ted Husing came to Boston in January of 1927 to be the director of radio station WBET. According to a 1929 article, Husing remained in Boston only until July and returned to New York to do announcing on station WHN. See Jean Pelletier, “Ted Husing, Versatile, Gay, Columbia Chain Announcer, Spices Life With Variety,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 20, 1929: 70.

39 “Off the Air,” Radiolog, October 4, 1931:15.

40 “Radio Chatter: New England,” Variety, September 11, 1934: 36.

41 “What’s on the Air?” Boston Globe, May 10, 1928: 29.

42 “First Baseball Game Saturday.”

43 “Braves Games to Be Broadcast,” Boston Herald, March 17, 1929: 34.

44 “Fred Hoey to Help Manage Garden.”“Fred Hoey Resigns His Garden Position,” Boston Globe, January 16, 1931: 31 “Dunn’s First Action to Retain Hoey,” Boston Globe, January 17, 1931: 9.

45 John J. Hallahan, “Capacity Crowd Expected at Garden as Stanley Cup Holders and Champions of 1927-1928 Clash,” Boston Globe, November 19, 1929: 28.

46 Bob Coyne, “Hello Everybody.” Boston Post, June 20, 1931: 12.

47 Halper, Boston Radio: 1920-2010.

48 John Barry, “When Referee Is Out of the Limelight,” Boston Globe, December 28, 1930: 27.

49 “Old-Timers Day Game Broadcast,” Boston Herald, August 31, 1930:27.

50 “Our Mail Bag,” Boston Herald, October 13, 1930: 14.

51 Burt Whitman, “Baseball Fan Writes Urging Fred Hoey Be Given ‘Day’ for His Baseball Broadcasting,” Boston Herald, August 27, 1930: 28.

52 Ibid.

53 Burt Whitman, “Fuchs Plans Day for Fred Hoey in June,” Boston Herald, January 8, 1931: 31.

54 Burt Whitman, “Fighting Braves Return Home Today to Open Six-Game Series With League-Leading Cardinals,” Boston Herald, June 18, 1931: 21.

55 Burt Whitman, “Fred Hoey Day Proves Lucky One for Tribe,” Boston Herald, June 21, 1932: 22.

56 “Hoey on Radio in World Series.” Boston Herald, September 26, 1933: 1, 27.

57 “Boston Hears Collins Complement M’Manus,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1933: 1.

58 Ted Patterson, “First Series Aircaster – Writer Grantland Rice,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1972: 11.

59 “Cold Puts Hoey Off Series Radio.” Boston Herald, October 4, 1933: 1.

60 Walter Graham. “World Series Notes.” Springfield Republican, October 7, 1933: 6.

61 “Cold Puts Hoey Off Series Radio.”; Victor O. Jones, “Fred Hoey Suffers From Bad Cold, and His Voice Fails Him,” Boston Globe, October 4, 1933: 1; “First Series Aircaster.”

62 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game: The Acclaimed Chronicle of Baseball Radio & Television Broadcasting – From 1921 to the Present. Updated Edition. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 23.

63 “Fred Hoey Selected to Broadcast Series,” Boston Globe, September 26, 1933: 20.

64 Jack Buck, Rob Rains, and Bob Broeg, Jack Buck: “That’s a Winner!” (Champaign, Illinois: Sagamore Publishers, 1997), 5.

65 Bob Coyne, “Hello Everybody,” Boston Post, June 20, 1931: 12.

66 Garry Brown, “Love Those Baseball Broadcasters,” Springfield Republican, June 21, 1987: D-12.

67 Brands.

68 Brands.

69 RadioLog, April 23, 1933: 15.

70 “Deserved Recognition,” Lowell Sun, September 28, 1933: 12.

71 Arthur Sampson, “Competition, Not the Smashing of Records, Theme of Heptagonal Meet Tomorrow,” Boston Herald, May 8, 1936: 48.

72 In 1936, The Sporting News conducted a fan poll to determine baseball’s most popular announcers. The September 17 edition (“Hoey and Bingham in Lead in Radio Popularity Voting”) showed Hoey in first place. Harry Hartman was the eventual winner of the poll (“Fans Vote Leadership to Harry Hartman and Harry Johnson in Air Popularity Poll,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1936: 5).

73 “Fred Hoey, ‘Voice of Baseball,’ Fired; Sponsors Want ‘Chatterbox Type,” Boston Herald, December 22, 1936: 1. The games were sponsored by General Mills and Socony Vacuum Oil.

74 Ibid.

75 One such example is the “Bob Dunbar” column on December 25, 1936.

76 “Protest Removal of Fred Hoey,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1936: 2.

77 “Fred Hoey Again Broadcasts Games,” Boston Globe, January 1, 1937: 1.

78 Hy Hurwitz, “Frankie Frisch Signs to Broadcast Local Ball Games,” Boston Globe, March 16, 1939: 9.

79 Ibid. The new sponsorship, according to the Boston Herald, was the Atlantic Refining Company, which was pushing for a change in broadcasters.

80 “Fred Hoey Out, Frisch Named,” Boston Herald, March 16, 1939: 1.

81 An ad appeared in the March 27 edition of the Boston Herald declaring, “Attention Baseball Fans of New England. Do you favor FRED HOEY for broadcasting the baseball games? Come in and sign petition or tel. Cap. 7000 for copies and we will deliver.” The Fred Hoey Booster Headquarters was listed as being at 34-36 Province Street in Boston.

82 “Fred Hoey Returns Today, WBZ, 6:15 P.M.,” Boston Globe, May 8, 1939: 11.

83 According to his obituary in the Berkshire Eagle, November 18, 1949.

84 “Hobbies of the WBZ Gang,” Boston Globe, July 23, 1939: B40.

85 “Fred Hoey Dies, Famed Here as Broadcaster,” Boston Herald, November 18, 1949: 1, 36; “Hoey, Popular Sports Writer, Official and Broadcaster, Dead,” Berkshire Eagle, November 18, 1949: 23.

86 “Fred J. Hoey,” Boston Traveler, November 21, 1949.

87 “Ex-Sportscaster Fred Hoey Dead,” Boston Globe, November 18, 1949: 26. Although Hoey’s death was officially ruled accidental, there are reasons to believe it may have been a suicide. The phrase “Take the gas pipe” was a euphemism to describe committing suicide (See “Take the gas pipe” in Jonathan Green, ed., Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2005), 1411). Hoey had been ill, and a cause of death by suicide would have prevented him from having a Catholic burial. Most writers of the time were reluctant to even use the word “suicide.” Credit to Donna Halper for bringing this information to the author’s attention.

88 “Former Baseball Broadcaster Fred Hoey Dies,” Boston Traveler, November 18, 1949: 28.

89 “Jack Onslow May Manage Braves’ Farm Team,” Boston Globe, September 20, 1950: 14.

90 “Ex-Sportscaster Fred Hoey Dead.”

91 “Mailbag – Our Readers Write on Hunters’ Day, Fred Hoey,” Boston Herald Traveler, September 20, 1972: 28.

Full Name

Frederick James Hoey

Born

May 11, 1885 at Boston, MA (US)

Died

November 17, 1949 at Winthrop, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.