Fred Mitchell

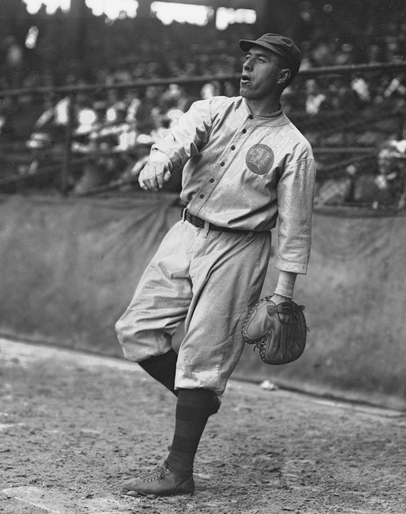

A life in baseball is how one might best describe the life of Fred Mitchell. He pitched in the very first game ever played by the Boston Red Sox franchise (an exhibition game in Charlottesville, Virginia), and 18 years later managed the Chicago Cubs against the Red Sox in the 1918 World Series. His major-league playing career ran from 1901 to 1913; he appeared as a pitcher in 97 games and recorded a 31-49 record with a 4.10 earned run average. At the plate, he was a .210 hitter in 572 at-bats spread across 201 games. At one time or another, he played every infield position, the outfield, and even caught 62 games for the New York Highlanders in 1910. He was one of the few who played for the Red Sox, the Boston Braves, and the Yankees (albeit while the teams were known as the Americans, Braves, and Highlanders.)

A life in baseball is how one might best describe the life of Fred Mitchell. He pitched in the very first game ever played by the Boston Red Sox franchise (an exhibition game in Charlottesville, Virginia), and 18 years later managed the Chicago Cubs against the Red Sox in the 1918 World Series. His major-league playing career ran from 1901 to 1913; he appeared as a pitcher in 97 games and recorded a 31-49 record with a 4.10 earned run average. At the plate, he was a .210 hitter in 572 at-bats spread across 201 games. At one time or another, he played every infield position, the outfield, and even caught 62 games for the New York Highlanders in 1910. He was one of the few who played for the Red Sox, the Boston Braves, and the Yankees (albeit while the teams were known as the Americans, Braves, and Highlanders.)

Mitchell managed the Cubs for four years (1917-1920) and the Braves for the three succeeding years (1921-1923), then resumed work as baseball coach at Harvard, for which he worked until he retired in 1939. He was the manager of Harvard’s team from 1926-1938.

He was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, as Frederick Francis Yapp. Fred’s granddaughter Lisa Mitchell says her great-grandmother Elizabeth’s maiden name was Mitchell and Fred used the name professionally simply to make life easier. “The family tombstone in Stow (Massachusetts) is still under Yapp.”1 It’s understandable that one might prefer to dodge the sort of catcalls that might come one’s way with the surname Yapp – with “yap” being a slang word for mouth, we can imagine all the taunts and ribbing: “Shut your big yap” and the like. An article in the Chicago Daily Tribune said it was Boston Americans manager Jimmy Collins who urged Mitchell to change his name because he feared that the ribbing of the fans could drive him out of baseball.2 His birth date is listed in the baseball record books as June 5, 1878.

Fred changed both his first and last names legally on August 20, 1943 – from Frederick to Fred and from Yapp to Mitchell. The same document his daughter Dorothy still has also changed the surname for her mother Mabel, and that of her brother Fred and herself. The third child in the family was already married and had assumed her husband’s name, so she was not included.3

Fred’s parents were Charles Yapp, listed in the 1880 Census as a groom in Cambridge, aged 28, having been born in England and becoming a U.S. citizen in 1871. His wife, Elizabeth, 25, was “keeping house,” with three young children: William, who was 4 years old at the time, Emma (age 2), and Frederick (age 7 months). All three children are listed as born in Massachusetts. Regarding the child named Emma that is listed in the census record, the family is convinced that there was no daughter named Emma. Fred’s daughter has the family Bible and a number of family records, and there is no indication, nor does she recall any mention of anyone named Emma. There was a later daughter named Mabel, who was born in October 1880. It must be noted that census information is notably unreliable; but showing Fred as seven months old could fit with his reported June 5, 1878, birthdate, if the census takers began collecting information in early 1879. The 1900 Census had Fred as born in 1887, clearly wrong – or he would have made his major-league debut at the age of 13.

Elizabeth had been born in Ireland (according to the 1880 Census) or England (as was stated in the 1900 Census). She became a naturalized American citizen in 1872. Fred was the middle of three children, his daughter Dorothy says, born between William and a sister named Mabel. Furthermore, she adds, “I’m pretty sure my grandmother and grandfather (Yapp) were not citizens of the U.S., though the census may have said so. I remember in World War II some kind of official documents had to be obtained for anybody who was not a citizen, and Grandma had to obtain one. (Grandpa was dead.)”4

The 1879 Cambridge city directory showed Charles Yapp as a “hostler” at the Massachusetts stables at 90 Washington, two half-blocks from this author’s current residence. In 1880, the family lived at 137 North Harvard Street.

Twenty years later, when Fred was just a year away from becoming a professional baseball player for the Boston Americans, the 1900 Census had Charles Yapp working as a horse shoer and residing at 9 Appian Way in the Allston section of Boston, on the other side of the Charles River from Cambridge. His two sons were in the same trade, William working as a horse trainer, and Fred as an assistant horse shoer. Charles Yapp was apparently active in competitive horse racing in the Greater Boston area; his name turns up as a driver in trotter racing results from the early 1880s into the mid-1890s, traveling as far as Saratoga, New York, and the state of Maine. One race reported in the Boston Globe as late as September 1910 featured two Yapps, perhaps Charley Yapp and his son William. A feature story in the April 21, 1889, Globe described Charley as “a thickly-set man, standing about 5 feet 9 inches and weighs about 160 pounds in the sulky. He has the reputation of going through a field as coolly as any man who ever drove a horse and he is not particular as to the chances he takes. He drives to win and has put as many horses to the front in proportion to the number he has handled as any one.” Though a profession of some danger, he had never suffered an injury of any kind. Some eight years later, however, Charles seems to have borne financial misfortune, declared insolvent as a racing track lessee and manager.5

The family also lived in Lawrence, Massachusetts, for a while. Fred played second base at school there, and a bit of semipro ball. In 1896, Fred’s father leased a half-mile racetrack in Concord, New Hampshire, and the Yapps moved there for two years. The lease included a 30-room hotel, complete with bar, and Fred became the “all-round man clerk and bartender.” He also played some semipro ball, both in Lawrence (both the Boston Globe and the Harvard Crimson say that Mitchell played for the 1897 Lawrence club in the New England League as a pitcher) and in Concord, where he pitched for a local man named Al Larsson. Unfortunately, when Charles Yapp staged a race meet at the track, the weather was bad and he “went broke” – he had to forfeit the lease and the family moved back to Boston — to Allston. Fred stayed on to play baseball, but at the end of the month, he wrote his daughter in a 1968 letter, “Larsson jumped town owing the players a month’s salary. I was dead broke and hungry.” Most of the players went back to their hometowns, but Mitchell met up with the manager of the Plymouth (New Hampshire) Fair, who came to Concord looking for the Larsson team to come play a couple of games at the fair. He had $500 to spend. Mitchell assembled a team from players around Concord, including a high-school catcher and a pitcher named Honey Annon, to whom he paid $20. “Our uniforms were of all colors, and we were a sight to look at,” the letter said. The ragtag bunch was put up at the fair’s expense, but they wore their spikes into the hotel and cut up the carpet and scratched the highly-polished floors, almost getting themselves thrown out.6

Honey Annon won the first game, and Mitchell won the second. When Fred was paid, the skeptical promoter asked if the mismatched aggregation really was the Larsson team. “There were a few fill-ins,” Mitchell admitted. “Well, they looked funny, but they sure could play ball,” the man replied. Fred Mitchell’s first job as a manager had been a success. More than 20 years later, while Mitchell was managing the Cubs, John McGraw beckoned him into the bar at New York’s Imperial Hotel and introduced him to his friend Al Larsson. “I think I’ve met Mr. Larsson before,” Fred said. “He left me stranded in Concord, New Hampshire, and he owes me $150.” “That’s nothing,” McGraw replied. “He left me stranded in Cuba.” Larsson blamed the Concord matter on his brother.7

After the fair – Mitchell says Annon was the only player he paid – he joined the rest of the family in Allston. His father still had no work, but after a while Fred began to work for Austin’s Livery Stable in Melrose, for $15 a week. He slept in the hayloft on a cot, taking care of 16 horses, and washed their buggies and harnesses each night. “I delivered three doctors’ horses and buggies before eight o’clock each morning and hitched them to posts in front of each doctor’s home.” This was another day and time. After three months, Fred quit and moved back home, where his father had borrowed some money and bought a blacksmith shop on Beach Street in Brookline, next to Boston. Fred worked there for a while and played a few semipro games around town to pick up a few dollars from time to time.

As for Fred and baseball, he seems to first turn up in the Boston Globe (as Yapp), pitching and hitting cleanup for the Cambridge Athletic Association in a July 1, 1899, game won, 13-10, by the Brighton YMCA. He tripled and homered in the game, but his pitching (dubbed “a heady game,” in which he struck out eight and walked one) was undercut by 10 Cambridge errors, six by shortstop Murphy.

There was a younger child in the family by the time of the 1900 Census – Mabel, born in October 1880 and working as an assistant bookkeeper; it appears that William had married a Scotswoman named Agnes and the two of them had a young daughter, Mary, born in 1898.

The book Red Sox Century, by Glenn Stout and Dick Johnson, has a photograph said to be of Mitchell with the 1900 Boston Nationals on page 7. But he never played for them that year, and his first appearance in professional baseball was as a member of the Boston Americans in 1901. It was only in 1906 that he had his first taste of minor-league ball, and it was in another country, playing for the Toronto Maple Leafs. Author Johnson surmised that the photograph was probably taken in spring training when Mitchell might have been a candidate for the team, but he didn’t make the final cut.8 Mitchell’s daughter and grand-daughter both are firm that the man in the photograph is not Fred Mitchell.

Fred told his daughter how he came to become a member of the very first Boston Americans team. An “old catcher” named Harry Pope caught Fred in Allston, and he’d spent a few summers catching for a team called the Roses in St. John, New Brunswick. In the summer of 1900, he talked Fred into traveling there with him and they took the boat from Boston. “I won most of the games I pitched for the Roses, and attracted the attention of John Graham, the track coach at Harvard, who spent his summer vacation in St. John. He recommended me to Hughie Duffy when we returned to Boston.” Hall of Famer Duffy was looking for players to sign up for the new American League team to be founded in Boston, and Duffy’s brother-in-law, Mike Moore, signed Mitchell early in 1901 for a $50 advance against a contract of $300 per month. Another player for the Roses, Larry McLean, also signed with the new team, and both were given tickets to Charlottesville, Virginia, for the first spring training.

Charles Yapp had moved his family to the countryside by the 1910 Census. He’s listed as a farmer in Stow, Massachusetts. Elizabeth was now, oddly, six years younger than her husband, rather than the three years younger she had been in 1880, and she was now listed as neither from England nor Ireland, but of Scot English heritage (the 1920 Census gives her birthplace as Scotland). Fred, age 32, is listed in 1910 as a “ball player.” No others were shown in the home. Mitchell purchased the 93-acre farm in Stow for his parents in 1906, according to a July 8, 1983, article in the Stow Villager.

The Chicago Tribune article from December 19, 1916, noted that Mitch was playing for the Eastern League’s Lawrence team in 1900 when the Americans purchased his contract; there’s a problem with this, however: There was no Lawrence team in the Eastern League (or in organized baseball) in 1900. There had been a team in Lawrence in 1899, managed by Tim Murnane. Mitchell probably played for Lawrence in 1899 and then St. John in 1900.

The first practice of the new American League Boston franchise was held on April 1, 1901, on the grounds of the Charlottesville YMCA, the very afternoon of the day when Collins and Chick Stahl arrived in town. There were 12 players in all, Cy Young being given permission to get into shape at home. Games were planned for the weekend against the University of Virginia and other colleges in the area. By his own assessment, Mitchell wrote, “I was a little wild, but fast, and had a good curve ball. One of the older players started to rave about me to Mgr. Collins. ‘Jimmy,’ he said, ‘this kid has got it!’ Collins picked up a bat and came up to the plate. I blew a few fast ones past him and he called me over to him and said, ‘Young fellow, you can work with the older pitchers from now on, and if you want a rubdown, you go up to the trainer of the University of Virginia and he’ll take care of you.’ I was a pretty happy kid that night. I knew I had made the Club!”9

The first exhibition game the Boston Americans ever played took place on the road, on April 5, 1901. The Washington Post’s account of the game said that all four of the Virginia team’s hits were made off Kane, and that both Mitchell and Connor held them hitless, though Mitchell walked one and hit another batter. “Mitchell showed the most speed,” said the Globe. He also showed some speed as the experienced horseman he was. Several of the players rented horses on a Sunday to ride up to visit Thomas Jefferson’s home, near Charlottesville. “I thought I’d have a little fun. I put my horse into a fast trot, then a gallop, and the other horses started to follow me. You never saw such bouncing in your life. They were hanging on for dear life and hollering at me to pull up. I pulled up after a bit and most of the boys got off the horses and walked back leading their horses. Some of them couldn’t walk naturally for two or three days.”10

On April 26, it was Win Kellum who had the honor of pitching the first regular-season game for the franchise. Win lost, 10-6, to Baltimore – the franchise that moved to New York in 1903 and eventually became the Yankees. The next day, Mitchell saw some duty. Cy Young started the game, but was both wild and hittable. Boston was down 11-3 after six innings, and Collins called in Mitchell to finish the game. Baltimore manager John McGraw was coaching on the sidelines and tried to rattle Mitchell by calling out the names of each of the great hitters as they came to bat. It didn’t work; he allowed just two hits and one run, and collected a hit himself in his first major-league at-bat. He struck out his second time up. The final score was 12-6.11

Mitchell’s first start was in Chicago on June 1, and the White Sox scored five runs in the bottom of the first, the biggest blow a bases-clearing triple that followed a single, a walk, a hit batsman, and two errors. From that point on, Mitchell shut them down, allowing just one hit in the eighth and one in the ninth, while Boston rang up 10 runs in all. He later recounted that first day to the Chicago Tribune: “I was scared stiff and the first inning was awful. I was shaking with stage fright and walked two or three guys and then someone swatted one. Freddie Parent chose that time to kick a couple of grounders.” Down 5-0, Mitchell was pleased to be picked up by a teammate. “There was one fellow on the club at that time who was my friend, and that was Buck Freeman. He came in from right field after the inning and I remember just what he said to Jimmy Collins. ‘You’re not going to take the kid out, are you, Jim?’ ‘Not on your life,’ answered Jim. I went back and had my head with me from then on and stopped the White Sox.” Mitchell went on to describe the two-run homer Freeman hit in the fourth inning and the three-run homer he hit in the eighth.12 Mitchell (and Buck and the Boston bats) won the game, 10-5.

Mitchell won his second start as well, 7-4, in Milwaukee. His first start at the team’s home field, the Huntington Avenue Grounds on June 17, saw him win the first game of a doubleheader from the White Sox, 11-1 (allowing five hits, with his “slow curves” noted in the papers) while Cy Young won the afternoon game, 10-4. The one run was unearned, due to an error by Buck Freeman.

It wasn’t all good; Mitchell was pounded by Cleveland on the 24th, defeated 7-1. He was ineffective in a relief stint in July, though he’d handily beaten Baltimore on Independence Day. A couple of times he was banged out of the box early, leaving in the first inning on July 27. As the year wore on, there seemed to be more times he faltered; he wound up his first year with a 6-6 record and a 3.81 earned run average, the fourth pitcher on the team behind Cy Young (33-10, 1.62 ERA), George Winter (16-12, 2.80), and Ted Lewis (16-17, 3.53). His batting average was .159 (7-for-44, with two triples). In a postseason benefit game in Boston against the White Sox, Mitchell gamely played second base, but committed five errors. The following day, he pitched and lost in Lynn against a picked team but it was no hard-fought game; Cy Young played in right field with the aid of a bicycle. Mitchell played right field in another exhibition game, against Greenfield, and pitched and lost a 4-3 game against players from Franklin and Marlboro on October 5. (All these teams were from Massachusetts.)

It wasn’t all good; Mitchell was pounded by Cleveland on the 24th, defeated 7-1. He was ineffective in a relief stint in July, though he’d handily beaten Baltimore on Independence Day. A couple of times he was banged out of the box early, leaving in the first inning on July 27. As the year wore on, there seemed to be more times he faltered; he wound up his first year with a 6-6 record and a 3.81 earned run average, the fourth pitcher on the team behind Cy Young (33-10, 1.62 ERA), George Winter (16-12, 2.80), and Ted Lewis (16-17, 3.53). His batting average was .159 (7-for-44, with two triples). In a postseason benefit game in Boston against the White Sox, Mitchell gamely played second base, but committed five errors. The following day, he pitched and lost in Lynn against a picked team but it was no hard-fought game; Cy Young played in right field with the aid of a bicycle. Mitchell played right field in another exhibition game, against Greenfield, and pitched and lost a 4-3 game against players from Franklin and Marlboro on October 5. (All these teams were from Massachusetts.)

Fred Mitchell was back with Boston in 1902, but he was admittedly “green” and the team had quite a few seasoned pitchers. It wasn’t clear how much work he would get. He appeared in just one game before he was sent to the Philadelphia Athletics. He’d been used only in spring training and exhibition games (losing to Hoboken, 6-3, on May 11 due to costly errors). His one game for Boston was in the May 30 doubleheader against Detroit, in relief of Pep Deininger, pitching the final four innings and seeing a 5-5 tie become a 10-5 loss. The Boston Globe termed the pitching of both men “far below the standard of the suburban league.” On June 2, as the team headed out on a road trip, Mitchell was “loaned to Connie Mack of Philadelphia.”13 As Mitchell explained it to his daughter, “Connie Mack had some trouble – losing players over in Philadelphia – and Jimmy Collins, our manager, came to me and said, ‘How would you like to go to Philadelphia, over to Connie Mack?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘If I could get regular work, I’d like to go.’” Mack secured Rube Waddell from the Giants, and picked up some other people. “We got together and won the pennant!”14 Waddell and Mitchell roomed together.

Had there been a World Series in 1902, Mitchell might have played in it, though Rube Waddell, Eddie Plank, and Bert Husting would have been the starters. The Athletics won the AL pennant (Boston finished third), and Mitchell was 5-7, with a 3.59 ERA. As with Boston, he walked far more men than he struck out. Despite winning the pennant, there was no one to play — it was only in 1903 that the first World Series was played — and in 1903, Mitchell was playing for the Philadelphia Phillies. Retrosheet says that before the season began he “jumped from the Philadelphia Athletics to the Philadelphia Phillies.” That’s the same word Mitchell used in his 1968 interview. He said he’d gone to Mack’s office at the start of 1903 and asked for a raise. Mack turned him down flat. (Mitchell had been 5-8 with a 3.59 ERA; there were at least four A’s pitchers much better than he.) Mitchell told Mack that since he didn’t have a contract, “I’m going to shift for myself. … I’m going to jump.”15 The two Philadelphia teams met in the preseason spring series and Mitchell shut down the Athletics in the first game (1-0 against Eddie Plank) and the fourth (2-0 against Waddell.)

He won his first two starts in the regular season — against the Boston Nationals (Beaneaters) on Patriots Day, and shutting out the Brooklyn Superbas on April 24. It was a year in which he won 11 games for the seventh-place Phils, but he lost 17 games. Nonetheless, Mitchell took advantage of the time, he told his daughter: “I commenced to learn something about pitching.” No Phillies starter won more than 13. He hurt his arm in 1904 and his 4-7 showing wasn’t impressive enough to warrant keeping him, so a deal was made to send him to Brooklyn later in the year, where he won two and lost five. His arm was still bad, and in 1905, Mitchell was 3-7 for Brooklyn. Thus ended his major-league pitching career. Fred had filled in as a position player in 12 games in 1904 — nine of them at first base. He played a smattering of games in the infield in ’05, too, before being cut loose in late August. In his obituary, the Boston Herald cited a “chronic arm ailment” as ending his 1905 season. He next turned up in the major leagues as a catcher, for the New York Highlanders in 1910.

The 5-foot-10, 185-pound right-hander was signed by manager Ed Barrow of the Eastern League (Class A) Toronto Maple Leafs, and pitched three seasons there, from 1906 through 1908. Earned run averages weren’t computed in the league at the time, but existing stats do show his most active season of all (239 innings) in 1906, under Barrow, and an 11-15 record for a last-place team. He was one of four Toronto pitchers to record 11 or more wins. In 1907, he was 6-3 in an even 100 innings of work. He was able to get in more work in 1908, throwing 166 innings with a 6-10 mark, including a no-hitter against Montreal. In the three years, his WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) was a very respectable 1.152. If all the runs he allowed were earned runs, which they surely were not, he’d have posted an ERA of around 3.50. The actual figure would have been substantially lower.

In 1909, none of the major-league clubs had picked Mitchell up and even though his arm seemed to be better, he still couldn’t snap off an effective curveball. He decided he’d become a catcher, and told the Toronto manager, Joe Kelley, “I’m going to be a catcher or else I’m going home.”16 He was talked into sticking around, and when two of the Toronto catchers got hurt, Mitchell moved from throwing to receiving. He appeared in 109 games for the Maple Leafs as the team’s first-string catcher. He came through at the plate as well, batting .295. He’d earned himself a promotion back into the American League, and caught for New York in 1910, signed in January and joining the team for spring training in Athens, Georgia, under manager George Stallings. He appeared in 68 games, almost precisely splitting playing time with Jeff Sweeney, who had 19 more at-bats. Mitchell’s .230 was better than Sweeney’s .200 but it was Sweeney who stuck with the Highlanders and Mitchell whose playing career was finished (save for four plate appearances with the Boston Braves in 1913 – in which he singled once, executed a sacrifice, and struck out twice.) A third catcher on the 1910 New York team was Mitchell’s former teammate with Boston in 1901 and 1902, Lou Criger.

Mitchell played in the postseason for the Highlanders as they fell in a city series against the Giants, Mitchell catching right to the very last game of the year. On January 3, 1911, the Highlanders sold Mitchell to Rochester in the Eastern League. He was one of three players sent to Rochester, apparently as — in effect — players to be named later in a deal that allowed New York to bring up catcher Walter Blair late in 1910. There’s a story behind the sale. Mitch and Lou Criger had become suspicious that Hal Chase was throwing games (“he was a little on the crooked side”). Stallings said he wouldn’t manage the team as long as Chase was on it. New York owner Farrell fired Stallings and made Chase manager! Chase heard that Mitchell had accused him in a meeting with Farrell and sold him and Jimmy Austin, and fired Criger.

Stallings had been fired in mid-September 1910, and spent 1911 and 1912 managing in Buffalo. Mitchell rejoined Stallings in Buffalo after the 1911 season (he’d hit .292 for the Rochester Bronchos in 1911.) It’s a little difficult to pin down some of Mitchell’s moves, but a March 19, 1912, item in the Hartford Courant reports that he has “been in charge of the Buffalo teams in the absence of Manager Stallings.” Mitchell hit .232 for the Double-A Bisons. Stallings became manager of the Boston Braves in 1913 and acquired Mitchell (“the stocky Buffalo catcher”) from Buffalo, planning to use him “as instructor and trainer of his young catchers and pitchers.”17 Mitchell even appeared in those four games for the Braves. In 1911, Fred had married Mabel Dorothy Goulding, and she came to stay at the farm on Walcott Street in Stow. In 1915, the couple had their first child, also naming her Mabel. . Her second daughter she then named Dorothy. When the third child turned out to be a boy, he was appropriately named Frederick F. III.

In early 1914, Mitchell – though “of the George Stallings aggregation” — worked coaching the baseball team at the Georgia Military College of Milledgeville.18 Mitchell was on the Braves roster as a catcher but, the Washington Post reported, “he never plays, his duty being to warm up and instruct the young pitchers.”19 In effect, he was the team’s pitching coach, in an era which had less formal nomenclature for coaches. These were the “Miracle Braves” of 1914, who had a losing record as late as July 31 (44-45, nine games out of first place) but went on to win the pennant by winning 27 of their last 33 games.

Looking ahead to the World Series, Stallings closed his remarks to newsmen by declaring as one of his most valuable men, “Fred Mitchell, my right eye.” A Stallings-bylined article in the Boston Globe added, “The fans do not appreciate the work Mitchell is called upon to do. … He is the hardest worker on the team.” He detailed some of Mitchell’s instructional work with Paul Strand and George Davis. The three Braves aces (Bill James, 26-7; Dick Rudolph, 26-10; and Lefty Tyler, 16-13), Stallings wrote, “Mitchell, almost single-handed, is responsible for their remarkable showing this year. Mitchell has worked with the catchers with equal care and has made [Hank] Gowdy, once turned back by McGraw, one of the best backstops in the league.”20 Stallings also praised Mitchell’s work coaching runners and batters during games. Braves swept the World Series from the purportedly unbeatable Philadelphia Athletics in four games. Sportswriter Frederick Lieb heaped praised on Mitchell, declaring that their success “would not have been possible with the battery coach, Fred Mitchell … one of the few men who ever played in the majors on both ends of the battery.” Lieb agreed with Stallings as to the three Braves pitchers, but quoted Stallings as giving Mitchell credit for George Davis’s no-hitter: “The kid never could have done it without ‘Mitch’ having told him how to pitch to each batter.”21

That December, Mitchell worked training ballplayers at St. Mark’s School, in Southborough, Massachusetts. He also worked as a scout for the Braves, and in mid-February was reported at Dartmouth trying to sign shortstop Fletcher Low. Later in the month, he headed for Macon for spring training, where he took on Braves coaching duties once more and carried through the full 1915 season, even added to the reserve list at the end of the year – though there were some hoops he had to jump through. When rosters had to be cut to 21 men, he had been put on waivers and was dropped from the active roster, working as a “scout” once more. When rosters expanded, he was signed again as a player and resumed coaching at third base. He actually had done some scouting, with Art Nehf perhaps his best signing.

On December 1, 1915, the Harvard Crimson reported that Mitchell had been appointed coach of Harvard’s baseball team, but would work for the Braves as well, simply turning up later than usual for the Braves. On the 7th, the Braves officially gave him his unconditional release, allowing him to take the position with Harvard.

Working with the Harvard nine saw one early success: On April 10, 1916, the varsity team took on the Boston Red Sox, world champions both in 1915 and again in 1916, in an exhibition game at Fenway Park. Harvard shut out the Red Sox, 1-0, both teams collecting five hits. Eddie Mahan pitched for Harvard. The Crimson posted a 21-3-1 season. Because of the World War, Harvard did not field a team in 1917. When baseball resumed, Mitchell’s replacement as Harvard head coach was old friend Hugh Duffy.

Mitchell became acting manager of the Braves in early August, when Stallings was suspended for three days “for words addressed to Umpire Rigler” after the August 2 game. The Braves apparently decided to better lock Mitchell in, and signed him in September to a three-year contract that prevented him from continuing as head coach of the Harvard team, but he took charge of each fall’s practice season for the university team. It was a “dual job” that required a little give-and-take from both sides regarding scheduling. Just two months later, word began to circulate that the Chicago Cubs were considering Mitchell as manager to take over from Joe Tinker, assuming that the Braves would let him out of their contract. Stallings said that, despite having worked with him for 10 years, “I would not stand in his way if there is an opportunity for him to better himself, but I will not give him away. He is too valuable a man, and besides, I had to pay the Buffalo club for him when I took over the management of the Braves.”22

The Cubs may have actually wanted Stallings, but taken Mitchell instead. They traded for him, sending outfielder Joe Kelly and some cash to acquire Mitchell from the Braves, and Cubs owner Charles Weeghman signed him to a two-year contract on December 14, 1916. The next day’s Chicago Tribune wrote that Weeghman had traveled to New York determined to secure John McGraw, George Stallings, or Fred Mitchell. “If Mitchell is good enough for the Braves, he’s good enough for the Cubs,” the owner declared (and saved himself a fair amount of money in the process, as Mitchell’s salary going into negotiations was reportedly $5,000 compared with $20,000 for either of the other more experienced men. “I know Chicago needs rebuilding,” he told the Tribune.

That seemed like an understatement at the time. The Tribune pointed out that most of the bigger-name players on the team had passed their prime, and that there were only “about half a dozen men of undisputed major league ability.”23 The Sporting News correspondent from Boston declared, “Good old Mitchell was handed over to the tender mercies of the bunch of restaurateurs, meat packers, chewing gum makers, and others who own the Cubs. … Mitchell knows what he is up against, but he is reconciled and even hopeful.”24 Within two years, the Cubs won the pennant.

Mitchell got the team off to a strong start in 1917. By May 17, they were 22-9 and Grantland Rice’s column in the May 19 Boston Globe recalled how instrumental Mitchell had been with the Miracle Braves of 1914. Taking over the Cubs, Rice wrote, “the general dope was that he had tail-end material and faced a famine. He was given a ball club composed in the main of athletes cast adrift, and many of these were injured or dismantled or out of gear.” Why were they playing so well? “Mitchell is the type of manager capable of lifting the best from each player’s system.” The Cubs finished in fifth place, not much different from the year before, but there was a sense that things were getting better rather than the foreboding sense under Tinker that they were sure to get worse.

Weeghman spent some money in the offseason, acquiring Grover Cleveland Alexander and Bill Killefer, and was hunting for a couple of other players as well. As William Wrigley purchased increasingly larger shares of the Cubs, and replaced Weeghman as principal owner, there was more reason for hope.

In 1918, while managing the Cubs, Mitchell may have been the first to employ what is today known as the Williams shift. When first implemented by Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau to defend against left-handed slugger Ted Williams, it was initially known as the Boudreau shift — but giving it Williams’s name may have inadvertently harkened back to Mitchell’s innovative stacking up of fielders on the right side of the diamond against left-handed hitter Cy Williams in 1918, his first year with the Phillies. Cy had been with the Cubs for the prior six seasons, and Mitchell would have seen him hit all year long in 1917.

The Cubs breezed through the abbreviated 1918 season, finishing up a full 10½ games ahead of the second-place New York Giants. Veteran southpaw Hippo Vaughn had another excellent year, his 22-10 record leading the league in wins. His 1.74 ERA also led the league. Claude Hendrix was another 20-game winner (20-7, 2.78 ERA) and Lefty Tyler was every bit as good (19-8, 2.00). The pitching staff’s ERA as a whole was a miserly 2.18, though the Red Sox staff ERA was just 2.31. The Cubs were odds-on favorites going into the September 5 start of the World Series; their team batting average also gave them an edge — .265 to Boston’s .249.

Babe Ruth just barely beat Vaughn, 1-0, in the first game, but beat him Ruth did. Tyler gave the Cubs a 3-1 win in Game Two, and the battle was joined. The Red Sox won it in six games, despite Cubs pitchers collectively registering a stupendous 1.04 earned-run average across all six games, holding the Red Sox to a team batting average of .186, and despite outscoring Boston 10-9. It was almost as close a low-scoring season as one could have, and many sportswriters simply ascribed the difference to more of the breaks going Boston’s way. Talking privately with his daughter, Mitchell was asked how the Red Sox had been able to beat the Cubs. He said, simply enough, “They had pretty good pitching and they had a little better hitting ballclub than mine, but the games were very close. They could have been turned either way.”

Had Grover Cleveland Alexander not been taken off to war early in the 1918 season, he might well have made all the difference. Alexander had won 30 or more games three years in a row for the Phillies. He was traded to the Cubs in December 1917, but pitched in only three games before he was drafted. Mitchell told his daughter that he’d tried hard to buy Rogers Hornsby, too, and secured Wrigley’s authority to offer as much as $125,000, but Branch Rickey of the Cardinals somewhat reluctantly turned him down: “We can’t make that deal. We’d love to make it, but if we sold Hornsby we might as well toss in the franchise,” Rickey said.25 Mitchell had been the man who spotted shortstop Charlie Hollocher, playing for Portland in the Pacific Coast League. He spotted him through his careful reading of The Sporting News, and decided to wire the Portland president to ask how much it would take. “$5,000 and a pitcher” was the reply. Mitchell closed the deal, and Hollocher reported to the Cubs in the spring of 1918, hitting .316 in his first season in big-league baseball.

Mitchell added the position of president of the Cubs to his portfolio in December 1918, and soon hired the man who became his successor: Bill Veeck Sr., whom Mitchell plucked from a position as a sportswriter for the Chicago American and installed as business manager of the ballclub, offering more than double the salary the paper had provided. It was, he said, a mistake. He complained to his daughter that when Philip Wrigley promised to split any dividends from the club with both Mitchell and Veeck, the new business manager stopped spending money: “Instead of buying ballplayers, he was standing pat, and my ballclub was getting old.” Mitchell asked Veeck one day where the scouting reports were, why he hadn’t been seeing them. Veeck had them in his desk drawer. Veeck wasn’t involved in baseball operations but had decided on his own that the players being scouted weren’t worth investing in. Veeck apparently bad-mouthed Mitchell and worked the board of directors sufficiently against him that Mitchell was out after the 1920 season and Veeck was installed as the new president. In Mitchell’s four years at the helm, the Cubs had won 308 games and lost 269, with the one pennant.

As soon as word got out, Mitchell received wires from the Braves, the Yankees, and one from Harry Frazee of the Red Sox. The Yanks wanted him as a coach; no, thanks. He waited on Frazee for two or three days, but the Sox owner was under the weather, and so he took up the offer from owner George Grant of the Braves, joining as field manager from 1921 to 1923, then as business manager after the Braves brought in Dave Bancroft as field manager. Mitchell’s tenure was disappointing in terms of results: 168-274. The Braves finished fourth in 1921, with a marginal winning record, but lost an even 100 games in both 1922 and 1923, dead last in ’22 and only a step out of the cellar in ’23. Right-hander Joe Oeschger was a 20-game winner the first year, but collapsed to become a 21-game loser the second and posted a poor 5-15 record the third. His ERA had plunged, but few on the team performed as well.

After being relieved of his post on the field, Mitchell remained as business manager of the Braves and continued to work as a scout. In the meantime, he was able to work things out with Harvard in January 1924 that he could coach the Harvard batterymen – the pitchers and catchers. On taking an initial three-year position with the college team, he told the Harvard Crimson, “I shall be able to put in every afternoon until the middle of April,” said Mitchell. “I want all the pitchers and catchers in college – both Freshman and Varsity – to report at the Locker Building this Wednesday. The routine work will begin Thursday.”26 He worked for the Braves in the mornings, and the afternoons at the university.

Mitchell finally resigned from both positions in 1938 to retire to his home in Newton Centre, outside Boston. There were times when the positions conflicted, such as in March 1925, when the Braves called him urgently to their St. Petersburg spring training camp; Mitchell promised Harvard he’d put in more time to make up for the lost time.27 Harvard was sufficiently satisfied with his work ethic and results, and that December the college appointed him head coach of the team on a three-year contract. He was taking the place of the resigning E.W. Mahan – whom Mitch had coached as a Harvard student back in the spring of 1916.28 One of his assistants beginning in 1926 was Fred Parent, a teammate from the 1901 and 1902 Boston Americans.

Another former Red Sox player, albeit from the time after Mitchell had left the team and it had adopted the name, was Harold Janvrin, who joined as a coach in 1930. One of the better products of Harvard at the time was Charlie Devens (Class of 1932), who pitched for a while for the Yankees. He told the Crimson, “Coach Mitchell’s coaching, together with that of Herb Pennock and Cy Perkins of the New York Yankees, have been the chief factor in whatever pitching success I have enjoyed thus far.”29

Prompting Mitchell’s 1938 decision to resign was some of the politics within the athletics department at Harvard. For a while, the college experimented with a “noncoaching system” meant to empower the players more, with Mitchell and the other coaches more in the background. Some felt this placed too much of a burden on the team captain, who was – after all – a student. Among those who feared losing Mitchell was captain Ulysses Lupien of the Class of 1939. Lupien wrote a letter to the Crimson in March 1938, reading in part, “We are especially privileged to have a man of Fred Mitchell’s character and ability as our coach. We wish to express publicly our respect and confidence in him.” Mitchell did resign. Lupien debuted with the Red Sox in September 1940. At Harvard, reports The Second H Book of Harvard Athletics, Mitchell oversaw teams compiling a record of 216-134 (with a few ties); Fred Mitchell was inducted into Harvard’s Hall of Fame in 1958.

Mitchell continued to live in Greater Boston, and was feted at a number of events and anniversaries over the years. In May 1951, he was among many former players celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Boston Americans. He noted how concerned they had been as to whether the new team would catch on. “We could see both parks from the train,” he recalled, as well as how pleased they were that the Americans had outdrawn the Nationals by a huge margin. Remembering some of the deceptions they’d used in the early days, he added, “I yearn for the days when we’d warm up a right-hander in front of the grandstand and then bring out a lefty who had been warming up under the grandstand. That would foul up a batting order.”30 The very next month, Mitchell was back for another ceremony, this one at Braves Field celebrating the 75th anniversary of the National League.

Fred’s obituary says he left his two daughters, Mabel L. Bassett of Los Angeles and Dorothy Patti of Needham, and son Fred Mitchell Jr. of Needham. Fred Jr. passed away from cancer in 1998 at age 71, but as of late 2009, Mabel was 94 and Dorothy was 85.

This biography can be found in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin. It is also included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

The sources used for this article are identified within the text. This biography was greatly enriched by the assistance of Fred’s granddaughter Lisa Mitchell. The author also consulted Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com, and Mitchell’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 E-mail communication July 7, 2009.

2 Chicago Tribune, December 15, 1916.

3 E-mail communication from Dorothy Patti, October 27, 2009.

4 E-mail communication from Dorothy Patti, October 26, 2009. Dorothy explains the listing of England as Elizabeth’s place of birth as perhaps a minor fib: “The Irish were looked down on in Massachusetts and she didn’t want anyone to think she was an Irish Catholic. Her older sister, my Aunt Mary Mitchell, told us this behind Grandma’s back. She probably also fibbed about being six years younger than her husband, instead of three.”

5 Boston Globe, September 10, 1897.

6 There are references in the Chicago Tribune of December 15, 1916, and the Washington Post of December 19, 1916. A considerable amount of material on Mitchell’s early years comes from a letter he wrote his daughter Mabel Mitchell Bassett in 1968, following a lengthy interview she did with him on July 13, 1968.

7 Fred Mitchell 1968 letter to Mabel Mitchell Bassett.

8 Communication from Richard A. Johnson, September 14, 2009.

9 Letter to Mabel Mitchell Bassett, 1968.

10 Letter to Mabel Mitchell Bassett, 1968.

11 Mabel Mitchell Bassett interview with Fred Mitchell, July 13, 1968.

12 Chicago Tribune, January 9, 1917.

13 Boston Globe, June 3, 1902.

14 Mabel Mitchell Bassett interview with Fred Mitchell, July 13, 1968.

15 Mabel Mitchell Bassett interview with Fred Mitchell, July 13, 1968.

16 Mabel Mitchell Bassett interview with Fred Mitchell, July 13, 1968.

17 Christian Science Monitor, February 27, 1913.

18 Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1914.

19 Washington Post, August 30, 1914.

20 Boston Globe, October 8, 1914.

21 The Sporting News, October 6, 1948.

22 Los Angeles Times, December 6, 1916.

23 Chicago Tribune, December 17, 1916.

24 The Sporting News, December 21, 1916.

25 Mabel Mitchell Bassett interview with Fred Mitchell, July 13, 1968.

26 Harvard Crimson, January 7, 1924.

27 Harvard Crimson, March 6, 1925.

28 Harvard Crimson, December 7, 1925.

29 Harvard Crimson, November 18, 1933.

30 The Sporting News, May 23, 1951.

Full Name

Frederick Francis Mitchell

Born

June 5, 1878 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

Died

October 13, 1970 at Newton, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.