Frenchy Bordagaray

“He’s either the poorest great third baseman or the greatest poor third baseman.”1

“He’s either the poorest great third baseman or the greatest poor third baseman.”1

In perhaps one of the best non-Yogi-Berra quotes in baseball history, this was Branch Rickey’s assessment of Frenchy Bordagaray, a colorful outfielder/third baseman who played for several teams in the 1930s and 1940s. He was free-spirited enough to fit in with both the Gas House Gang St. Louis Cardinals and the daffy Brooklyn Dodgers, and some of his shenanigans, especially those with Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel, are legendary. Some are even true.

Stanley George Bordagaray was born on January 3, 1910, in Coalinga, California, one of seven children born to Dominique and Louise Bordagaray, who were among the original settlers of the San Joaquin Valley. Dominique was a hotel owner and sheep rancher. Bordagaray’s family was of Basque descent. (In Europe the Basques inhabit an area of southern France and northern Spain.) Stanley and his six brothers were all nicknamed Frenchy.

Bordagaray played baseball and football and ran track at Coalinga High School. After high school he entered Fresno State College, where he continued playing baseball and football. He also played semipro ball while in school, and it was a semipro connection that led him to entering Organized Baseball.

Army Armstrong, a semipro teammate of Bordagaray’s, recommended to the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League in 1931 that they give him a tryout. Bordagaray impressed team management with his speed and was signed to a contract on July 30 of that year. In his first game he went 2-for-3 against the Oakland Oaks. Frenchy got into 70 games that season, batted .373 with five home runs, and cemented a spot for the following season.

Bordagaray played an exhausting 173 games for the Senators in 1932, batting .322 with 223 hits in 692 at-bats. Frenchy also gave new meaning to the term “horse-racing” when he actually ran a 100-yard race against a horse named Eat ’Em Raw at the California State Fair in Sacramento. Bordagaray ended up eating the horse’s dust, as the nag ran the distance in 8.75 seconds. Frenchy’s time was not reported.

Perhaps Sacramento management wasn’t happy with the race results, because they offered Bordagaray a pay cut for the 1933 season. In what became a regular rite, Frenchy demanded a pay increase and left spring training on March 14.

“The trouble with Bordagaray is that he thinks he is a Babe Ruth and wants to be paid accordingly,” said team owner Lew Moreing. “We can’t relish that stuff.”2

It seems that Moreing could, in fact, “relish that stuff” because Bordagaray was back the next day.3 He went on to have one of the best seasons of his baseball career, hitting .351 with a career-high 7 home runs in 117 games.

Bordagaray’s impressive numbers motivated the Chicago White Sox to purchase his contract for $15,000 before the 1934 season. He made an impressive major-league debut on Opening Day against the Detroit Tigers at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, getting a pinch hit and scoring a run in an 8-3 White Sox loss. He went on to appear in 29 games, including 17 as an outfielder, and batted.322 in 87 at-bats. (He was 8-for-12 as a pinch-hitter.) Still, the White Sox returned him to Sacramento on June 9. Accounts differ as to whether the White Sox weren’t pleased with Bordagaray’s play or simply decided they wanted their $15,000 back. Either way, he played 117 games for the Senators and despite getting off to a slow start, managed to hit .321.

That season Bordagaray performed the first feat of flakiness that made him a raconteur’s delight. In a game against the Portland Beavers, the General, as he was called in Sacramento, evidently forgot to go out with the rest of the troops to his position in right field. None of his teammates noticed until Portland center fielder Nino Bongiovanni hit a double to Frenchy’s vacated spot.

Nonetheless, the Brooklyn Dodgers were interested enough in Bordagaray to acquire him after the season in exchange for Johnny Frederick and Art Herring plus cash. Frenchy joined the Dodgers (whose manager was one Charles Dillon “Casey” Stengel) for the 1935 season.

Babe Ruth brought a new era to baseball in the 1920s with his home runs. Stengel and Bordagaray revived an old era when they teamed up, except in this case it was vaudeville. No one would confuse this band of Dodgers with the Boys of Summer teams of the 1950s. The Dodgers of the 1920s and 1930s were a ragtag group. The franchise was mired in debt and playing in a deteriorating Ebbets Field. The team acquired the nickname “The Daffiness Boys” because of the oddball characters and strange plays that made the Dodgers entertaining, even if they weren’t successful.

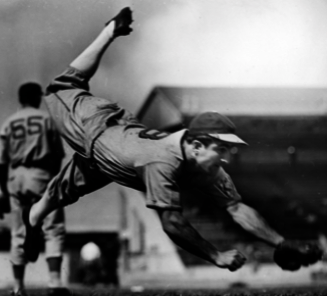

Statistically, Bordagaray’s 1935 and 1936 seasons with the Dodgers were pretty good. In his first full campaign as a major leaguer, he hit .282 with one home run, 39 RBIs, and 69 runs scored. He was third in the league with 18 stolen bases. In 1936 he hit .315 with 4 home runs, 31 runs batted in, 63 runs scored, and 12 stolen bases in 125 games. But the numbers don’t convey the color that Frenchy brought to the team.

During one exhibition game, Bordagaray’s hat fell off while he was chasing a fly ball. Frenchy, being Frenchy, stopped to retrieve the hat, and then continued chasing the ball.

“Stengel stood in the dugout in the dugout with his arms hanging and his mouth open. He couldn’t believe what he was seeing,” said former Dodger Buddy Hassett. “When Frenchy got back to the dugout, Stengel asked him what he thought he was doing out there. ‘The cap wasn’t going anywhere, Bordagaray,’ said Stengel, ‘but the ball was.’ ‘I forgot,’ Frenchy said.”4

There was also the time Frenchy was standing on second base when he was suddenly picked off. Stengel went out to argue, to no avail, and when he went back to the dugout he asked Bordagaray what happened. Frenchy explained that he was tapping his toe on the bag and that the infielder caught him between taps.

Another story had Bordagaray tagged out on a play at the plate when he tried to score standing up instead of sliding. His explanation to Stengel was that he didn’t slide because he had some cigars in his back pocket that he didn’t want to ruin. Stengel fined Bordagaray $50 or $100, depending on who is telling the tale. The next day he hit a home run and slid into every bag on his trip around the bases.5

The pièce de résistance had to be the scandal Frenchy caused when he showed up at spring training in 1936 sporting a wispy mustache. After the 1935 season, Frenchy grew the mustache for a small, uncredited part in a film directed by John Ford, The Prisoner of Shark Island, and was still wearing it when spring training arrived. This was an era when players were clean-shaven, so the facial hair created a media sensation.

“The new mustache of the noted movie extra is a delicate affair of a distinctly Ronald Colman pattern,” wrote Tommy Holmes in the Brooklyn Eagle.6 “Stengel says it was the prettiest he ever saw, but Frenchy says that Casey is jealous and threatens to wear it from now on.”7

Bordagaray was ahead of his time when it came to self-promotion with the media, and he kept the ink-stained wretches busy writing articles about the mustache. He even arrived at camp one day sporting a monocle to go with the mustache; sort of an Adolphe Menjou meets Colonel Klink. This went on for a while until Stengel finally had enough.

“After I had it about two months, Casey called me into the clubhouse and said, ‘If anyone’s going to be a clown on this club, it’s going to be me,’” Bordagaray said.8

Whether Dodgers management was tired of the comedy act or just wanted to make changes, they fired Stengel after the season, and traded Bordagaray to St. Louis.

They may also have traded him simply because he didn’t have the baseball smarts that turn a player with his talent into a star. After Frenchy was gone, Holmes remarked that he wasn’t a great ballplayer despite talent, speed, charisma, and a good attitude.

“With all those qualities you’d think he’d be a really good ball player,” wrote Holmes. “And yet he makes you eat holes in your hat. The reason, it seems to me, is lack of big league instinct in such fundamentals as base running and fly catching.”9

The St. Louis Cardinals of 1937 were not the powerful Gas House Gang that won the World Series in 1934. They still had some of their stars, including Joe Medwick, Pepper Martin, and Dizzy Dean, but they were no longer a contender. Bordagaray got into 96 games that season, batting .293 with one home run and 37 RBIs. He played 50 games at third base and 28 in the outfield. The man whose father had hoped he would be a violinist also joined teammate Pepper Martin’s Mudcat Band as fiddle player and first washboard. The band toured the theater circuit for $50 a show. It was also popular at the Cardinals’ 1938 spring-training camp, with Frenchy, of course, wowing them in the aisles.

“Frenchy is the sensation,” said an article by the Associated Press. His washboard has a three-tone phone, bicycle bells, and even an electric light for special renditions.”10

The 1938 Cardinals finished under .500 for the first time in six years with a 71-80 record (plus five ties). On the surface, it would seem that Bordagaray’s contribution was ordinary, with a .282 batting average in 81 games, zero home runs and only 21 runs batted in. He did, however, excel in a very difficult role, that of pinch-hitter. He had 20 pinch hits, just two off the record then of 22 set in 1932 by Sam Leslie of the Giants. (As of 2014 the record holder was John Vander Wal of the Colorado Rockies, with 28 in 1995.) Bordagaray’s batting average of .465 as a pinch-hitter was at the time the second highest batting average ever for a pinch hitter, behind only the .467 attained by Smead Jolley of the White Sox in 1931 (As of 2014 Ed Kranepool of the 1974 New York Mets holds the single-season record,.486.)11

Being a good pinch-hitter apparently wasn’t enough for the Cardinals to keep Frenchy on the big-league roster. After the 1938 season, they wanted to send him down to their farm club in Rochester. He refused to report, so the team traded him to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Dusty Cooke. The trade worked in Bordagaray’s favor because he not only stayed in the big leagues, he also got his first chance to appear in the World Series.

It’s safe to say that Bordagaray’s contribution was not integral to the Reds’ winning the 1939 National League pennant. He batted only .197 in 122 at-bats with no home runs and 12 RBIs. He appeared as a pinch-runner in Games Two and Three of the World Series, and didn’t steal any bases or score any runs as the Reds were swept by the New York Yankees.

After the 1939 season, Bordagaray opened a nightclub in Cincinnati called Frenchy’s Barn, an event that found its way into the famous column of Walter Winchell: “Frenchy Bordagaray of the pennant-winning Cincinnati Reds team has opened a night club in that city. … Could it be, do you think, that the World Series beating by the N.Y. Yankees has affected his mind?”12

Perhaps Winchell had a point, because Frenchy’s 1939 statistics didn’t guarantee any job security, and he ended up going to the Yankees, along with Nino Bongiovanni, to complete a deal in which the Yankees sent Vince DiMaggio to the Reds in exchange for $40,000 and players to be named later.

A team that had just won four straight World Series wasn’t in great need of a .197 hitter, so the Bronx Bombers sent Frenchy to their Kansas City Blues farm club in the American Association. Frenchy tore up the league, pounding out 214 hits for a .358 average and a ticket to the Bronx for 1941.

The 1941 Yankees were a powerhouse team that won the American League pennant by 17 games. They had an outfield of Charlie Keller, Tommy Henrich, and Vince DiMaggio’s younger brother, so Bordagaray’s playing time was limited to just 16 starts in the outfield and 73 at-bats. He did manage to get a pinch-running appearance in Game Two of the World Series, which the Yankees lost. Perhaps somebody realized that Frenchy’s teams always lost in the World Series whenever he pinch-ran, so he stayed on the bench for the next three games, all won by the Yankees, and Frenchy had his one and only championship. Nonetheless, he didn’t enjoy playing with the Bronx Bombers. “(I) couldn’t have fun with them,” he said. “They were too serious. Snooty guys. Except Joe (DiMaggio). He’s the only one I got along with.”13

The Yankees, on the other hand, felt they could get along fine without Bordagaray, and sold him back to the Dodgers after he refused a demotion to Kansas City. Bordagaray spent the rest of his playing career in Flatbush. He played a total of 137 games in 1942 and 1943, batting a respectable .291, with no home runs and 24 RBIs. Wartime player shortages gave Bordagaray more playing time in 1944. He played in 130 games that year and batted .281 with 6 home runs and 51 RBIs, both highs for his major-league career. He also played more games at third base (98) than in any other season and made 15 errors there.

The 1945 season probably had Rickey’s opinion leaning toward “poorest great third baseman.” Frenchy played the hot corner as if it were the too-hot-to-handle corner, committing 19 errors in 166 chances for a woeful .886 fielding percentage. He batted .256 in 273 at-bats with 2 home runs and 49 RBIs. He played his last game on September 30, 1945. He was released before the start of the 1946 season.

By the end of his playing days, Bordagaray was still fun-loving, but was taking his career more seriously, both on the field and under it. He invested in a company that built cemeteries across the United States and made more money with the company than he did playing baseball. The Dodgers gave him a job as player-manager of the Trois-Rivieres Royals, their affiliate in the Class C Canadian-American League, in 1946. He justified the Dodgers’ faith in him by batting .363 and managing the team to the regular-season title with a 72-49 record as well as the league championship.

Bordagaray also played a small role in Branch Rickey’s effort to integrate major-league baseball. It is well known that Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier with the Montreal Royals of the International League in 1946, but Rickey had assigned African-American players to other levels as well. Pitchers John Wright and Roy Partlow had had trials in Montreal, but were sent down to Trois-Rivieres. Partlow went 10-1 and Wright was 12-8, and they both played significant roles in Trois-Rivieres’ drive to the championship.

“On the Three Rivers team, we had all nationalities: blacks, whites, Frenchmen, Jewish boys. We had the whole works,” Bordagaray noted. “The funny thing about it was I never thought of (Wright, who joined the team before Partlow) as black. I just thought of him as a ballplayer.”14

Frenchy’s success earned him a promotion to player-manager of the Greenville Spinners of the Class A South Atlantic League for 1947. It was there that a promising managerial career came to an end when he punched and spat on an umpire during a dispute in a July 15 game. He was suspended for 60 days and fined $50. The incident happened on the same day he was chosen Most Valuable Player for the 1946 season in the Canadian-American League. He never returned to Organized Baseball.

When told of the fine and suspension, he was quoted as saying, “I deserved something, but this is more than I expectorated.”15

After leaving baseball, Bordagaray, his wife, Victoria (whom he married in 1940), and their family moved to Kansas City, where he worked in the cemetery business until 1961. They then moved to Ventura, California, where Frenchy worked as sports supervisor for the Ventura Department of Sports and Recreation until 1988.

Looking back, Bordagaray acknowledged that he had fun as a ballplayer, but felt he could have played better. He once said in an interview that he never reached his peak because doctors failed to diagnose that he had hypoglycemia, a blood-sugar disorder that causes weakness.16

Bordagaray died in a Ventura nursing home on April 13, 2000, at the age of 90. He left his wife, four children, seven grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.

This biography originally appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Joanne Hulbert and J.G. Preston for providing materials for this article.

Sources

Honig, Donald, Baseball Between the Lines: Baseball in the Forties and Fifties As Told by the Men Who Played It (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993).

Spatz, Lyle, ed., The SABR Baseball List and Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007).

Zubiri, Nancy, A Travel Guide to Basque America: Families, Feasts and Festivals (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1998).

Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune

Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Burlington (Iowa) Hawk-Eye

Fresno (California) Bee Republican

Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News

Los Angeles Times

Middlesboro (Kentucky) Daily News

Reading (Pennsylvania) Times

Sports Illustrated

Baseball-reference.com

IMDB.com

Notes

1 Oscar Fraley, “Bordagaray Succeeds Among Flatbush Flock,” Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, June 14, 1944.

2 “Bordagaray Deserts Sacs In Pay Fuss,” Fresno Bee Republican, March 14, 1933.

3 The account of Bordagaray’s return was unclear as to whether he signed at the same amount as he received the previous year or with a slight raise. Anyway, it seems he avoided a pay cut.

4 Donald Honig, Baseball Between the Lines: Baseball in the Forties and Fifties As Told by the Men Who Played It, 57.

5 Stengel was reported to have fined Bordagaray $50 in August 1935 for not sliding when he should have, but the story about sliding into every base after hitting a home run the next day may be fictitious. The author could not find newspaper accounts of the incident, and former teammate Buddy Hassett did not mention it in an interview for the Honig book. It’s still a great story.

6 Ronald Colman was a British actor who won an Oscar Award for Best Actor in the 1947 film A Double Life.

7 Tommy Holmes, “Dodger Recruits Click In Training Workout,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 7, 1936.

8 Richard Goldstein, “Frenchy Bordagaray Is Dead; The Colorful Dodger Was 90,” New York Times, May 23, 2000.

9 Holmes, “Lack of Big League Fundamentals Raises Havoc With Bordagaray,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1936.

10 “Frankie Frisch Loses Some of His Wrinkles As Cards Become Gashouse Gang of Old,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, March 17, 1938.

11 The SABR Baseball List and Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007), 187.

12 Walter Winchell, “Walter Winchell on Broadway,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, November 3, 1939.

13 Jeff Meyers, “THE NEWS OF THE DAY: Frenchy Bordagaray, an 82-Year-Old Great-Grandfather Living in Ventura, Shocked the Baseball Establishment in the 1930’s With Such Gimmicks as Racing a Horse on Foot and Growing a Mustache, but His Flair Made Him a Media Darling,” Los Angeles Times, December 25, 1992.

14 Jules Tygiel, “Those Who Came After,” Sports Illustrated, June 27, 1983.

15 Julian Pitzer, “Sports Briefs,” Middlesboro (Kentucky) Daily News, January 30, 1948.

16 Meyers.

Full Name

Stanley George Bordagaray

Born

January 3, 1910 at Coalinga, CA (USA)

Died

April 13, 2000 at Ventura, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.