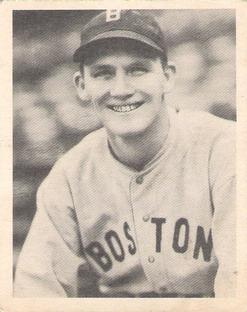

Fritz Ostermueller

Fritz Ostermueller was 41 years old when he took the mound on September 30, 1948, to make the final start of his 15-year major-league career. The Pittsburgh left-hander had played with four big-league teams; his lifetime ledger was even at 114 wins and 114 losses. In early September the Braves, Cardinals, Dodgers, and the surprising Pirates had been involved in a four-team battle for the National League pennant, but in midmonth Boston caught fire and pulled away from the other three clubs.

Fritz Ostermueller was 41 years old when he took the mound on September 30, 1948, to make the final start of his 15-year major-league career. The Pittsburgh left-hander had played with four big-league teams; his lifetime ledger was even at 114 wins and 114 losses. In early September the Braves, Cardinals, Dodgers, and the surprising Pirates had been involved in a four-team battle for the National League pennant, but in midmonth Boston caught fire and pulled away from the other three clubs.

On September 30, with four games left on the schedule, the Pirates and Dodgers trailed the second-place Cardinals by a single game. On that date Pittsburgh and St. Louis played a twin bill at Sportsman’s Park, and the Cardinals took the opener, 6-1. In the nightcap, Pirates skipper Billy Meyer picked Ostermueller to oppose the Redbirds’ 19-game winner, Harry “The Cat” Brecheen. Called “Old Folks” or “Ostey” by teammates and sportswriters, Fritz had pitched in tough luck in his two previous outings, losing to the Braves and Warren Spahn in a 2-1 heartbreaker on September 18, and then going down to defeat, 4-3, to the Reds six days later.

It was a must-win situation for Pittsburgh, and Ostermueller, in the second game of the doubleheader; a victory would keep the Pirates’ slim second-place hopes alive, and for Old Folks, it would restore his career record on the plus side of .500. St. Louis, however, touched Fritz for a run in the second inning, then added two more in the fifth, and Ostey was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the sixth. The Cardinals and Brecheen prevailed, 4-1; The Cat became a 20-game winner for the first time, and lowered his league-leading ERA to 2.24. Fritz took the loss, and three days later, Pittsburgh wound up the season in fourth place. The following week, Fritz Ostermueller announced his retirement from the game he had played professionally for 23 seasons.

Frederick Raymond “Fritz” Ostermueller was born on September 15, 1907, in Quincy, Illinois, to German immigrants George and Anna Wink Ostermueller. The second youngest of nine children, Fritz grew up with his seven brothers and one sister on a dairy farm, and after the cows were tended to, the boys played baseball in the pastures and, eventually, in the area’s Parish League.

Young Fritz attended St. John’s College in Quincy for a while, but his talents on the diamond took precedence over academics, and in 1926, at the age of 18, he signed to play professionally with his hometown Quincy Reds in the Class B Three-I League. The local team soon came under the umbrella of the St. Louis Cardinals, and Ostermueller began an eight-year journey with Branch Rickey’s “chain gang.” The youngster was assigned to Quincy again in 1927, but in August was sent to Wheeling, West Virginia, of the Middle Atlantic League. Ostermueller pitched in only two games for Wheeling; one was in Cumberland, Maryland, where on August 16, he married Faye Simpson of Milan, Missouri. The two first met in Quincy, courted there, and were delighted when Fritz was shipped back to the Three-I League team to finish out the season. Overall, with Quincy and Wheeling, Ostey’s record was eight wins and nine losses.

Ostermueller played in the Western Association in 1928 and 1929, and became a threat with the bat in addition to his growing skills on the pitching mound. In 1928 Eddie Dyer was the player-manager of the Topeka Jayhawks, and one day called on Fritz to start both games of a doubleheader against Joplin. The left-hander responded with complete game, 3-2 and 3-0 victories over the Miners, and his single plated the winning run in the first contest.

Ostermueller’s record was 12-12 in 1928, and the following year he was a 20-game winner. From 1930 to 1933, Fritz moved up and down the Cardinals’ farm ladder: St. Joseph, Greensboro, and Rochester. He was productive in his two seasons with Greensboro in the Piedmont League, winning 15 games in 1931 and 21 in 1932 to help the Patriots become the circuit’s playoff champions. Greensboro’s regular lineup was riddled by injuries in the 1932 postseason; Ostermueller was called on to play right field and first base, and the left-handed hitter responded with two home runs and five RBIs.

Ostermueller sparkled with Rochester in 1933, posting 16 wins and 7 losses, and led International League pitchers with a 2.44 ERA. Fritz also hit .315, including a pair of four-baggers; his season was cut short, however, by an attack of appendicitis, and he was operated on in late July. Several major-league clubs were interested in obtaining him for 1934 delivery, and the Boston Red Sox won out in the bidding, sending three players and cash to Rochester. Rickey was banking on Dizzy and Paul Dean to anchor the St. Louis pitching staff, and willingly surrendered his longtime southpaw farmhand.

Tom Yawkey, who had inherited 7 million dollars in 1933 from the estate of his uncle, William Yawkey, purchased the Red Sox. The elder Yawkey had been a part-owner of the Detroit Tigers, and Tom had set his sights on one day acquiring his own major-league team. Four days after receiving his legacy on his 30th birthday, Tom Yawkey paid one million dollars to Bob Quinn for the Red Sox franchise, and hired longtime major-league standout Eddie Collins to become Boston’s general manager.

Buoyed by the Yawkey bankroll and Collins’s keen eye for baseball talent, the Red Sox acquired future Hall of Fame catcher Rick Ferrell from the St. Louis Browns in May 1933. In June they parted with $100,000 cash to add infielder Bill Werber and pitcher George Pipgras from the New York Yankees. And Collins dealt with the cash-strapped Philadelphia Athletics in December, giving up $125,000 and two players to obtain infielder Max Bishop and hurlers Robert “Lefty” Grove and Rube Walberg.

In addition to Ostermueller, the Red Sox added two other rookies from the International League to the spring training roster for 1934: Baltimore outfielder Julius “Moose” Solters and Rochester catcher Gordie Hinkle. Solters was the 1933 International League batting champion, and Hinkle was Ostermueller’s batterymate at Rochester and several other stops in the Cardinals’ chain. Two other important acquisitions were manager Bucky Harris, signed after being dismissed as Detroit skipper, and veteran left-hander Herb Pennock, a veteran of 21 seasons with three American League clubs.

Ostermueller was 26 years old, weighed 175 pounds, and was an inch short of 6 feet tall when he reported to the Red Sox training base at Sarasota, Florida, in February 1934. At the time Fritz threw mostly side-arm and had a good fastball, curve, and change, but had been plagued by wildness most of his minor-league career. Harris placed his rookie pitcher under the tutelage of Pennock; the two worked to improve Ostey’s delivery and his control, and the student was impressive in spring outings. The Red Sox left training camp with Harris counting heavily on a pitching corps overloaded with lefties to carry the club. But Grove, with a sore arm, won only eight games; Rube Walberg triumphed just six times, and Pennock, in his swan song, logged just two victories. Southpaw Bob Weiland, after starting with just a single win and five losses, was traded to Cleveland on May 25 for right-hander Wes Ferrell, who became the staff ace. The time was ripe for Ostey to step in.

Ostermueller made his big-league debut on April 21, 1934, in a relief role in the fifth game of the season before the home folks at Fenway Park. The Yankees had a 6-5 lead when Fritz was summoned in the seventh inning with the bases loaded and two out. The rookie stymied the New Yorkers, recording seven outs, and Boston rallied to win, 9-6, giving Ostey his initial major-league victory. The freshman left-hander was spectacular again in relief on May 9, racking up the save with three scoreless frames in a 5-4 win over the Tigers. Entering the game in the seventh with the bases loaded and no outs, Fritz struck out Charlie Gehringer, and then induced a pair of groundouts.

Two days later he made his first start, hurling into the 11th inning at Fenway Park against Cleveland, only to lose, 6-5. Ostermueller faced the Browns on May 17, and took a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the eighth before allowing a two-run pinch homer to player-manager Rogers Hornsby; St. Louis rallied to win, 4-3. Fritz was on the beam in two straight complete games against Washington, winning 7-2 on June 3 at Griffith Stadium, and coming back five days later to post a 3-2, 12-inning victory. He also contributed two hits and scored the winning run in the final frame.

For the 1934 season, Ostermueller finished at 10-13, but he led Red Sox starters with a 3.49 ERA, seventh best in the American League. He pitched 198 2/3 innings in 33 appearances, and completed 10 of 23 starts. Fritz’s year was shortened on September 12 when he walked off the mound in the first inning at Tiger Stadium with an injury to his left shoulder. Ostey had some other memorable moments in his rookie year, including a Fourth of July triumph over the Yankees in relief of Wes Ferrell. Taking over in the fifth with bases loaded, no outs and the Red Sox clinging to a tenuous, 5-4 lead, he walked the first batter to tie the score but shut out New York the rest of the way and Boston rallied to win, 8-5.

On July 31 at Yankee Stadium, Ostermueller gave up Babe Ruth’s 703rd career home run as New York triumphed, 2-1. The Bambino socked another round-tripper off Fritz on August 11 at Fenway (No. 705), but in a losing cause, as Ostey pitched all the way to record a 13-inning, 3-2 victory. It was Ruth’s last season as a Yankee; after Fritz struck him out, he rewarded the rookie left-hander with an autographed baseball. The ball is now the centerpiece in the memorabilia collection of Sherrill Ostermueller Duesterhaus, the daughter of Fritz and Faye Ostermueller.

Eddie Collins parted with another $250,000 of Yawkey’s bankroll in the winter of 1935, purchasing shortstop and manager Joe Cronin from Washington; Cronin’s potent bat was needed to perk up the anemic Boston offense. Ostermueller enjoyed a good spring in Sarasota in 1935, but three physical maladies ruined his season. In April he was hit on the knee in batting practice, and on May 25 he took a shot in the face off the bat of the Tigers’ Hank Greenberg, damaging his nose, jaw, and some teeth. And on August 18, a liner by the Browns’ Moose Solters fractured a fibula in Fritz’s leg. His season record was 7-8; he beat Cleveland three times, and lost to both the Yankees and Tigers on three occasions. Two of his victories were notable; on June 8 he triumphed over the Yankees and Lefty Gomez, 4-2, surrendering six hits and garnering three safeties of his own. And on July 30, he struggled to an 11-4, complete-game win over Washington, though he gave up a dozen walks, along with four hits.

A hitter of great renown joined the Red Sox in 1936: Jimmie Foxx. The power hitter from the Athletics added some needed sock to the Boston attack for several years; in ’36 he batted .338, smacked 41 homers, and drove in 143 runs. Ostermueller saw more action on the mound that season, but his 10-16 record was disappointing. He started 23 games, completed seven, and worked 180 2/3 innings; he still suffered dizzy spells from Greenberg’s smash of the previous year. The Red Sox finished the season in sixth place; Wes Ferrell and Lefty Grove notched 20 and 17 wins, respectively.

Ostermueller made only seven starts in 1937, and pitched just 86 2/3 innings in 25 games. He was shut down at various times during the season by a chipped bone in his pitching elbow; Fritz didn’t pitch after August 8, and went under the knife of Dr. Robert Hyland in St. Louis at the close of the 1937 season.

Red Sox hitters clicked in 1938, leading the league in team batting with a .299 average, and the club finished in second place behind the Yankees. Foxx led the AL in hitting (.349) and RBIs (175), and belted 50 home runs. The lowest batting average of the regulars was rookie second baseman Bobby Doerr’s .289. The extra run support helped the pitching staff, including Ostermueller, who returned to form with 13 wins against 5 losses. He started the season strongly; on April 19, Fritz pitched six innings of one-hit ball in relief to beat the Yankees, 6-0. And six days later, he blanked the Senators, 7-0, on four hits.

Ostey batted .234 and totaled 175 hits in his major-league career without hitting a home run, although he belted several in the minors. On June 10, 1938, Ostermueller watched with irony as southpaw hurler Bill Lefebvre, signed off the campus of Holy Cross College by the Red Sox a few days earlier, made his big-league debut against the White Sox in a mop-up role. Lefebvre remained in the game to hit, and on the first pitch delivered to him in the major leagues, he lofted Monty Stratton’s offering over the left-field wall for a home run.

Rookie outfielder Ted Williams was a welcome addition to the Boston lineup in 1939; he paced the AL with 145 RBIs, batted .327, and clouted 31 home runs. Foxx was the league leader with 35 homers, and batted .360 to finish second to Joe DiMaggio’s .381. The Yankees took the flag again, distancing themselves from the runner-up Red Sox by 17 games. Ostermueller made 20 starts, won 11 games, lost 7, and recorded four saves. The left-hander was most effective against the Yankees, Browns, and Washington Senators, beating each club three times.

Fritz was ailing when he reported to Sarasota in February 1940. He arrived with influenza, along with a serious sinus condition, thought to be a delayed reaction to the line drive off Greenberg’s bat in 1935. Ostermueller was left behind when the Red Sox departed Florida, worked out with the Louisville farm club, and didn’t make his first start until May 12. He pitched seven innings against New York, allowed one earned run, yet it was all for naught; Red Ruffing shut out the Red Sox, 4-0. It wasn’t until July 17 that Fritz recorded his initial victory, beating the Tigers in a relief role. In what would be his final season in Boston, Ostey won only five games and lost nine. He made 16 starts, going the route in five of them.

Ostermueller had three highlight games late in 1940. On August 1, he beat the Indians and Mel Harder, 5-2. Fritz logged a complete-game seven-hitter, and Foxx, filling in at his old position at catcher, slammed a two-run homer. Four days later, the same battery took on the Yankees, and led the Red Sox to a 4-1 victory. Foxx contributed another two-run round-tripper and the southpaw pitched a seven-hitter. On September 27, Fritz took the mound for his final start in a Red Sox uniform, and defeated Washington in a 24-4 laugher. In December, Ostermueller and right-hander Denny Galehouse were sold to the St. Louis Browns for $30,000.

In 1941 the Browns trained in San Antonio, Texas, where Ostermueller and Galehouse joined veteran hurlers Bob Muncrief, George Caster, Johnny Allen, and Elden Auker. The lone left-hander in the group, Fritz did well in spring games, but was plagued by a sore arm during the season; he lost three games without logging a win. In February 1942, St. Louis sold Ostey to their Toledo farm club, where he resurrected his career with 11 victories and a 3.23 ERA. The Browns bought his contract back on July 26, and the portsider worked in 10 games, contributing three wins against a single loss to St. Louis’s rise to third place at season’s end.

The Browns trained in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, in 1943, due to wartime travel restrictions, and Ostermueller’s role was diminished when he was struck on the left elbow by a batted ball. Surgery followed to remove the elbow cap, and it forced a change in the left-hander’s windup, as a “catch” developed in his elbow. Sportswriter Vince Johnson of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette later wrote: “By bending low and swinging his arms in unison Fritz found that he could tell whether the elbow would ‘catch’ and then correct the trouble without interrupting his motion.” Two of Ostey’s future teammates also commented on the windup; Pittsburgh slugger Ralph Kiner said, “Fritz had an unusual windup; no one like it.” And 1947 Pirates second baseman Eddie Basinski said, “It wasn’t a true windmill; similar, but also partly a rocking motion.”

Ostermueller worked sparingly for the 1943 Browns; he was winless in three starts, and was charged with two losses. On July 15 he was part of a trade to the Brooklyn Dodgers that brought much-traveled hurler Louis “Bobo” Newsom to the Browns. Ostey didn’t want to go east because of the higher cost of living in New York, but Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey satisfied his demands, and the southpaw reported to Brooklyn. His baptism as a National Leaguer was spotty; Fritz relieved in six games before he injured his ankle while sliding into third base. Six weeks later, he started against the Braves, and was removed after pitching nine innings in a 2-2 tie. Also, because of his marital status, Ostermueller was classified 3-A in the military draft; then arthritis caused him to be rejected twice from military service in 1943.

Ostey’s career took several more turns in 1944. He began the season in the Dodgers’ rotation, and by May 14 had started four times, with three complete games and a pair of wins. Fritz’s sole loss in those four appearances was a heartbreaker; on April 27 Jim Tobin of the Braves tossed a no-hitter to beat the Dodgers, 2-0. Ostermueller surrendered only five hits, one of them a solo home run by Tobin.

In spite of his creditable work, Fritz again was relegated to the Brooklyn bullpen, and on May 27, Rickey put him on waivers. The move was controversial, as the veteran left-hander was only six weeks short of 10-year status in the majors, and with several teams in need of help on the mound, Ostey went unclaimed on the waiver wire. On May 30, Rickey swung a deal with Syracuse; to obtain outfielder Goody Rosen, he sent cash and pitchers Bill Lohrman and Ostermueller to the International League team. The two Dodger hurlers didn’t want to go back to the minor leagues, however, and refused to report to Syracuse. Two days later, Pittsburgh purchased Ostey’s contract from the International League club, and he was back in the majors.

Pirates manager Frankie Frisch welcomed his new acquisition, and Ostermueller responded with 11 victories and a staff-leading 2.73 ERA. Fritz beat New York and St. Louis three times each. It was a nice turnaround for the veteran hurler, as Pittsburgh finished the season in second place, while the Dodgers wound up in seventh, 42 games behind the pennant-winning Cardinals.

It was snowing when Ostey joined the Pirates for 1945 spring training in Muncie, Indiana. And personally, a dark cloud was hanging over his head; word came that he had been reclassified 1-A in the draft, and to prepare for induction into the Army sometime in April. Fritz chose to stay with the team through spring drills, and was the Pirates’ starting pitcher in the season opener in Cincinnati. The Reds’ Dain Clay spoiled the afternoon for the southpaw when he hit a grand-slam; Ostey left after four innings, and the Pirates eventually lost in 10 innings, 5-4. Fritz made one more start, losing to Chicago, 3-0, before being inducted into the Army and assigned to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. He was discharged three months later, on July 24, and rejoined the Pirates the following week. The southpaw recorded an overall 5-4 record in the broken season; he defeated St. Louis and Boston twice each, and lost three decisions to Chicago. The Pirates remained in the first division of the NL, placing fourth.

Pittsburgh baseball spiraled downward in 1946 and 1947; the club dropped to seventh in 1946, but welcomed rookie outfielder Ralph Kiner to the roster. Kiner’s 23 homers led the league, while Ostermueller topped the team’s hurlers with 13 wins and a 2.84 ERA. Fritz had a bittersweet day in St. Louis on July 7, 1946. Five hundred admirers from his hometown took a special train 140 miles to attend Fritz Ostermueller Day at Sportsman’s Park. Included in the gifts presented to the pitcher by the Quincy Boosters Club were a $500 check, a wristwatch, and a set of golf clubs. The Cardinals put a damper on the celebration two hours later, however, when they scored a run in the bottom of the ninth to beat Ostey and the Pirates, 4-3.

Frisch left as Pittsburgh skipper after 1946, and was succeeded by Billy Herman. A splurge in home runs couldn’t keep the Pirates out of the basement in 1947; Hank Greenberg came over from Detroit to finish his career, and supplied 25 four-baggers. Kiner, batting in front of Greenberg, upped his homer total to 51, and tied Johnny Mize for league honors. The quote, “Home run hitters drive Cadillacs, singles hitters drive Fords,” was originally credited as coming from Kiner, but the slugger later corrected the source. In October 2005, Kiner wrote, “Fritz was a great teammate and a good pitcher for us; he did coin the expression, not I.” Ostermueller’s 12 wins again were highest on the mound staff, and Pirates second baseman Eddie Basinski complimented his teammate by writing, “When Ostermueller pitched, I knew we had an excellent chance of winning.”

Ostermueller’s career came to a close in 1948; he finished the year at 8-11, but was a major factor in Pittsburgh’s run for the pennant. Manager Billy Meyer spotted him against the league’s best, and the veteran responded. In games with the Braves, he triumphed over Johnny Sain in 1-0 and 2-1 skirmishes, and was beaten 2-1 by Warren Spahn. Harry Brecheen of St. Louis beat Fritz twice, and in another classic game, the two lefties battled to a 10-inning, l-l tie halted by darkness. In his 1948 season debut, Fritz had a no-hitter going against the Reds until there were two outs in the seventh inning, but Hank Sauer ruined it with a homer. Fritz did gain a victory, 7-2.

Life after baseball was a busy time for Ostermueller. He and Faye had adopted a baby girl, Sherrill, in 1947, and retirement at home in Quincy allowed the couple to spend more time with their daughter. Fritz had other pursuits as well; he joined the American Legion, was a life member of the Quincy Lodge of Elks, and was an avid hunter. For several years he was part of the broadcasting crew for the minor-league Quincy Gems. Ostermueller was in the booth as color man on August 13, 1949, when Harry Caray, then the play-by-play voice of the St. Louis Cardinals, came to Quincy to work the Waterloo-Quincy game on Gems’ Boosters Night.

The Ostermuellers built a motel on their Quincy property, and Old Folks became the owner-operator of the aptly named Diamond Motel. The family took annual hunting vacations to the Rocky Mountains, and in 1956 Ostey was hospitalized in Missoula, Montana, after becoming ill. The first signs of colon cancer were discovered, and Fritz’s health declined. On September 15, 1957, his 50th birthday, Ostermueller became eligible to receive his major-league pension. Daughter Sherrill said, “I can still see him walking out our little lane to the mailbox; he wasn’t feeling good, but he would take that walk. He was so excited to receive his check.”

The crafty pitcher, whose southpaw deliveries were received by some of the game’s best catchers, including Hall of Famers Rick Ferrell and Al Lopez, succumbed to his illness, and died in Quincy on December 17, 1957.

For several years after his death, the Quincy Elks Lodge hosted an annual dinner to award the Fritz Ostermueller Memorial Trophy to a Quincy product who had gained national attention in sports. One of the recipients was Elvin Tappe, a graduate of Quincy High School and Quincy College, who later was a catcher and coach with the Chicago Cubs.

Faye Ostermueller took over as operator of the Diamond Motel after her husband’s death, later sold the property, and worked for a time as a reservations clerk with Holiday Inns. She died in Quincy on July 14, 2001, at the age of 92, and was buried next to her husband in Quincy’s Calvary Cemetery. Their only child, Sherrill Ostermueller Duesterhaus, resides in Missouri with her husband.

Sources

Fritz Ostermueller file at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library & Research Center

Scrapbook and clippings of Faye Ostermueller and Sherrill Duesterhaus

Conversations with Sherrill Duesterhaus

Eddie Basinski correspondence

Ralph Kiner correspondence

SABR ProQuest Historical Newspapers

Baseball Library.com (www.baseballlibrary.com)

Warren Corbett, SABR BioProject (Ralph Kiner)

Cleve, Craig Allen. Hardball on the Home Front. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2004.

Full Name

Frederick Raymond Ostermueller

Born

September 15, 1907 at Quincy, IL (USA)

Died

December 17, 1957 at Quincy, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.