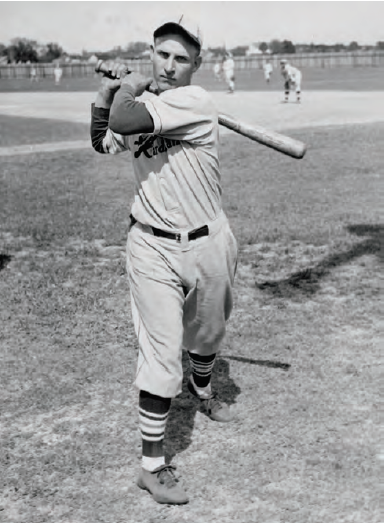

Gene Moore

The obituary published in The Sporting News when Gene Moore died centered on his having made his only World Series appearance because of “a weird circumstance.”1 Although accurate, the article overlooked the fact that Moore was a player of All-Star caliber, the type of player any manager would want on his team. Statistics did not reflect the intensity Moore brought to baseball.

The “weird circumstance” The Sporting News cited was a trade of catchers between the Washington Senators and the St. Louis Browns in March 1944, Washington’s Tony Giuliani for the Browns’ Rick Ferrell. Giuliani refused to go to the lowly Browns and instead retired. Moore was substituted for Giuliani. He too was reluctant to go to St. Louis for whom little success was forecast in 1944, and did so only after receiving a cash inducement from the Senators. So it was Moore rather than Giuliani who earned a World Series check that season.

Eugene Moore, Jr. was born in Lancaster, Texas, on August 26, 1909, to Eugene and Sarah Moore, the fifth of ten children. Like many of his era, Moore shaved a year off his birth – the player file at Baseball’s Hall of Fame shows his birth date as August 26, 1910.2 Eugene Sr. was a pitcher who spent nine years in the Texas League with brief major-league appearances in three seasons. Almost simultaneously with his son’s birth, Moore was called up to the Pittsburgh Pirates, making one appearance late in September 1909. He also pitched briefly for the Pirates in 1910 and for Cincinnati in 1912, compiling a career record of 2-2.

After retiring from the game, Moore Sr. returned to farming in Lancaster, near Dallas. Three of his sons showed enough talent to rate consideration as professionals. Neither Collins nor Hal Moore ever made it past tryouts, but Eugene Jr. went on to play ball in all or part of 14 major-league seasons.

Moore first came to prominence playing for Waxahachie High School, which at one point won 65 games in a row and featured two other future major leaguers, Paul Richards and Art Shires.3 After graduating and playing semipro ball for a year, Moore signed for $600 to pitch with Midland of the West Texas League in 1929.4 It quickly became apparent that his skills were better suited to playing the outfield than pitching. Appearing with five different clubs in his first three seasons, he hit over .300 at each stop, climbing rapidly from Class D to Double-A (then the highest minor-league classification.5 In September 1931 he played in four games for the Cincinnati Reds, itting .143 in 14 at-bats.

On December 24, 1931, Moore married Gladys Bryan in Dallas. The marriage produced two children, Robert Gene, born in 1933, and Donald Bryan, born in 1936.6

In 1932 Moore was back in the minors, playing for three Class B teams, Peoria of the Three-I League and Harrisburg and Elmira, both of the New York-Pennsylvania League. Transferred to the vast St. Louis Cardinal organization in 1933, he played well at Houston, Columbus, and Rochester, but, except for brief appearances was unable to crack a St. Louis outfield containing players like Joe Medwick, Terry Moore (no relation), and Jack Rothrock. He was with the world championship 1934 team in April and May before being sent back to the minors.

In September 1935 Moore was sold to Brooklyn after a solid season with Rochester. The Dodgers had plans to call him up for the final few games of the season, but word did not reach him until he arrived home in Texas.7 Moore was not destined to play for Brooklyn – yet. He was traded to the woeful Boston Bees (Braves) with pitcher Johnny Babich for Bees pitcher Fred Frankhouse.

Freedom from the vast Cardinal minor-league system was a gift, and joining the worst team in baseball was a great opportunity. Bert Keane in describing 1936’s rookie crop for the Hartford Courant wrote of Moore, “He can throw with accuracy and power. He hits for distance and when under way scurries around the bases like a scared rabbit.”8 Moore wasted no time showing the Bees the wisdom of their trade, hitting an opposite-field homer on his first at-bat in an exhibition game against the crosstown rival Red Sox – a particular skill at which the left-handed hitting Moore became quite proficient.9

Given the chance, Moore did not disappoint. He had an outstanding rookie season. Playing right field and appearing in 151 games, Moore hit .290, placing in the top ten in the National League in hits, doubles, triples, and home runs. Keane’s description of Moore’s throwing ability (“with accuracy and power”) was dead on. Moore’s 32 outfield assists led the majors.

Moore gave evidence of his opposite-field power early on. Playing at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh on May 1, the left-handed batter hammered two home runs, the second over the left-field fence. The New York Times noted, “Old-timers said this was the first time a left-handed batter performed that feat.”10 Less than two weeks later Moore showed a streak of independence not looked upon kindly by his manager, Bill McKechnie. Playing against Pittsburgh, he was ordered to bunt. Disregarding the sign, he swung away and tripled. McKechnie raked Moore over the coals – and watched him slam another triple later in the game.11 McKechnie must not have been too hard on Moore; he played the next day.

On August 25 Moore hit two doubles in the first inning of a game against St. Louis, tying the record for the most doubles by a player in an inning. His teammates hit five more doubles in the inning and the seven two-baggers were a record for the most by a team in an inning. (It was tied by the Cardinals in 2012.12)

Moore finished the 1936 season with a .290 batting average and 13 home runs. Thanks to his play and that of two other newcomers, Tony Cuccinello and Al Lopez, the Bees climbed from eighth place to sixth. Moore had another productive season in 1937. His average fell to .283 but his home runs rose to 16, a good number for that era. His assists dropped from 32 to 21, no doubt because baserunners no longer desired to challenge his arm, but he still led the league. The team improved again finishing over .500 in fifth place just behind the Cardinals. Moore was named to the National League’s squad for the All-Star Game. He didn’t start (the NL’s starting outfield was Paul Waner, Joe Medwick, and Frank Demaree), and grounded into a force play as a pinch-hittr.

Moore went back home to farming after the season. His father was ill, and Gene was helping to support his brothers, sisters, and mother as well as his wife and children. Eventually Moore bought a farm near Lancaster, Texas, raising cotton, corn, and wheat as well as pigs. His farm adjoined that of Dizzy Dean, whose career had taken an abrupt turn for the worse in 1937 after the All-Star Game.13 Earl Averill’s line drive broke the big toe on Dean’s left foot. Dean came back before the injury properly healed, hurt his arm in the process, and lost his effectiveness as a premier pitcher. That a player’s career could be changed by injury was part of the game. It happened to Moore the next season.

Moore played for a new manager in 1938, Casey Stengel having replaced McKechnie, who left to manage Cincinnati. Moore welcomed the opportunity to play for Stengel. “I know Manager Casey Stengel is a good man to play for, and I will do my best for him and for the club,” he wrote to general manager Bob Quinn. Stengel for his part believed Moore could use his speed to advantage by bunting more often.14 Although Moore honed his bunting skills, it did not mean he neglected other aspects of his offense. In the second game of the season, with the Bees down 4-2, he hit a grand slam to win the game.15 Ten days later Moore hit another grand slam to help win a 16-11 slugfest against the Phillies. The Bees were off to a good start; in late May they were in third place, close behind the Giants and Cubs.

On May 19 the Boston Globe reported that Moore was playing with neuralgia and an injured ankle.16 The next day the Globe reported that Moore was “badly handicapped by an injured ankle and would have to take a few days off to rest it.17 Moore was out of the lineup for a few days but came back going all-out; within a few weeks he injured a foot and elbow when he ran into the grandstand wall attempting to catch a foul ball.18

On June 11 the Bees were victimized by Cincinnati’s Johnny Vander Meer, who shut them down with the first of what would be two consecutive no-hitters. Moore, who drew one of Vander Meer’s three walks, was picked off first after catcher Ernie Lombardi caught a pop foul. Moore twisted his ankle trying to get back to the base and went out of the lineup for a week.19 In late June he was reported to have locked cartilage in his left knee and began playing with a knee brace.20 He continued to play, in one game crashing into Cuccinello as both went for a ball.21 On July 18 Moore collapsed chasing after a hit, and took himself out of the game. His season was over.22 He would never again perform as well as he had with Boston.

Moore had surgery to have cartilage removed from his knee. According to the practice of the time, he was placed on the voluntarily retired list. 23 Meanwhile, on August 30 his father died from the lingering effects of a brain tumor.

In December Stengel visited the convalescing Moore to see how he was faring. If Moore could come back, it would be a boon to Boston; his loss was considered the main reason the Bees had finished out of the first division.24 Stengel must have been less than impressed; Moore was traded to the Dodgers. Brooklyn had sent scout Ted McGrew to Moore’s farm and after “hitting a flock of fungoes to Gene” determined it was worth the chance to obtain his services. 25

It was a bad trade from the Dodgers’ perspective. Although Moore looked healthy in spring training, he had lost his stroke. He played in 107 games for the Dodgers in 1939 and hit just .225 with only three home runs. Brooklyn sold him back to Boston six weeks into the 1940 season. Although Moore’s batting average rebounded to a respectable .290, his loss of power proved permanent. After posting slugging averages in the range of .450 in his first two seasons with the Bees, Moore never topped .400 after 1940.

In February 1942 Moore was traded to the New York Yankees for Tommy Holmes. Overjoyed at being traded to a pennant contender, he was disappointed when he was sold less than three weeks later to Brooklyn’s top minor-league team, the Montreal Royals. Moore felt this was a setback; Montreal was glad to gain his services. Manager Clyde Sukeforth was said he was a “tailor-made player for the dimensions of the Montreal Park.”26 Sukeforth was correct. Moore had a solid year, hitting .315 and leading the league in triples, runs scored, and total bases. He led the Royals’ outfielders in assists with 13 – no mean feat considering he was playing alongside future Dodgers star Carl Furillo, who became renowned for having one of the best outfield arms in the game.

Normally a 32-year-old former major-league outfielder with bad legs could expect no higher level of play, but these were not ordinary times. Though World War II manpower requirements were high, Moore’s bad knees exempted him from the draft. It also made him attractive to major-league teams trying to fill their rosters. At season’s end Moore was purchased by the Washington Senators.

He joined a team that had finished in either sixth or seventh the previous four years. By 1943 teams experienced fluctuating rosters because of increasing draft demands. The Senators, in dealing with this challenge, amassed a mixture of players who had yet to be drafted or were exempt from the draft. They jumped to second place in 1943; Moore batted.268 as a backup outfielder and .400 as a pinch-hitter.

During the offseason Moore was on the trading block. Rumors had him going to the Yankees.27 That did not take place, but in March 1944 Moore was traded again. It was anything but a routine transaction.The Senators and St. Louis Browns traded catchers. Rick Ferrell went to Washington in exchange for Tony Giuliani.28 Giuliani balked at going to the Browns and retired. Browns owner Donald Barnes demanded cancellation of the transaction. Washington needed Ferrell. Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis backed Barnes, who then demanded Moore as Giuliani’s replacement.29 Moore was reluctant to report, but Senators owner Clark Griffith reportedly gave him a bonus to go.30 Giuliani’s perception of the situation proved amiss. Washington finished last in 1944 and the Browns won the pennant.

Barnes knew what he was about prying Moore from the Senators. He and general manager Bill DeWitt approached the game during the war by stocking the roster with “drunks, rogues cast off as troublemakers by others … worn and frayed strands of playing talent. …” 31 Moore was unfit for military service because he had no cartilage in either knee. At 34, he was one of the older players on the St. Louis roster. The Browns, like Washington, experienced ups and downs during the war, finishing third in 1942, sixth in 1943, and were not expected to do well in 1944.

What sort of person were the Browns getting? By all accounts, Moore was a quiet individual, not given to brag. In Harold Kaese’s history of the Boston Braves, Moore, while with Boston, was described as spending evenings as an inveterate “hotel lobby sitter.” Of his lobby sitting, the laconic Moore commented, “I went to High School like Art Shires (a very colorful and eccentric personality), and I just want to show we turn out all types there, quiet as well as noisy.”32

His habits did not change with the Browns. David Heller in his book on the 1944 Browns, described Moore’s demeanor and penchant for lobby-sitting; “He wasn’t vocal, and didn’t drink, usually hanging out with (first baseman George McQuinn) in hotel lobbies, both players relaxing by smoking cigars and watching the traffic of people around them.” Heller wrote that Moore’s nickname, Rowdy, was bestowed on him as one might call a tall person Shorty.33

Moore may have been devoid of color, but on a team of “drunks, rogues, and troublemakers,” his steady demeanor and serious approach to the game gave the team needed stability. Bill Borst, author of The Best of Seasons, portrayed Moore as a “steady presence,” invaluable during the pennant drive. 34 These were intangibles, hard to measure. By standard measures, Moore did not do well in 1944, hitting .238 with six home runs. Yet he came through at crucial times.

The Browns won their first nine games of the season, boosting the team’s confidence. Moore started hot, hitting .421 in the first five games of that streak. Leading the team in RBIs in May, he finished the month with a game-winning single against Washington on May 31. The victory put the Browns back in first place. Several days later, after St. Louis had lost three straight games to Cleveland and were losing a fourth, Moore was called on to pinch-hit, and hit the first pitch he saw for a game-winning grand slam.35 His hits were few, but when he hit they counted. On the last weekend of the season with the Browns trying to hold onto first place over Detroit, they played the Yankees. With St. Louis holding a 1-0 lead, Moore homered in the sixth inning for an insurance run in the Browns’ 2-0 victory. They clinched the pennant the next day, the last game of the season, and went into the World Series against the heavily favored Cardinals.

The Browns shocked the Cardinals, winning two of the first three games. However, the National Leaguers roared back to take the Series in six games. Cardinal pitching proved the difference, holding the Browns to a .183 average. Moore hit well at the beginning of the series, but went hitless in the last three games, and ended batting .182 for the Series. In Game One he singled with two outs in the fourth inning, and when McQuinn followed with a drive over the right-field pavilion at Sportsman’s Park, Moore became the first Brownie to score a run in a World Series. McQuinn’s homer proved enough to win the game 2-1 as the back-to-back hits were the only two safeties that day by the Browns. In the first inning of Game Four, with the Browns down 2-0 and a man on base, Moore drove the ball to deep center, but it was caught on a brilliant play by Johnny Hopp. It was one of the crucial plays of the Series. Moore and the Browns had nothing to be ashamed of; they played tough against the finest team of the era. The Browns’ losing share of the World Series receipts, $2,743.79 per full share, was the lowest received by players on a losing team since 1920.

As the 1945 season opened, World War II was nearing an end. Many regulars were coming back from the service, replacing those who had filled in. The Browns played well, finishing third behind Detroit. Moore hit creditably well, finishing at .260. The last game of the season Detroit needed a win to clinch the pennant. The Tigers won it in the top of the ninth at St. Louis thanks to Hank Greenberg’s grand slam. Moore had a run-scoring double. It was his last major-league game.

Moore finished his major-league career with a .270 average and a .400 slugging percentage. Although he signed to play in 1946, it was not to be.36 Gladys became ill and Moore left the game to take care of her. In early 1947 he was reactivated, and the Browns sold his contract to Toledo in the American Association.37 Moore refused to report, and soon word came out that he was in the scrap business at Laurel, Mississippi.38

According to Moore’s grandson Bryan, Gladys’s father, Selma Bryan, who operated junkyard businesses at several locations in Mississippi, offered Moore management of Laurel Steelworks. This, coupled with his wife’s illness and the ever-present pain in Moore’s knees, made retirement the feasible choice.39 Mrs. Moore’s illness continued for several years. In 1948 she had surgery for a ruptured disc and spinal fusion.40 (She recovered and lived until 1999, when she died at the age of 88.) Moore continued in the junk business until he retired and passed ownership of the business to his son Robert.

Over the years Moore made appearances at old-timer’s games, including reunions of the 1937 All Stars and the 1944 Browns. He hunted, fished, and started Little League in Laurel. He enjoyed his grandchildren, allowing them to play with several of his autographed baseballs. Moore spoke very little of his playing days, once telling grandson Bryan that if he spoke of his experiences, folks might think he was bragging. This was in keeping with how his daughter-in-law, Martha, Robert’s wife, and grandson Bryan remembered him: A mild, soft-spoken person.41

Moore died on March 12, 1978, in Jackson, Mississippi. He was 68. Mild and soft-spoken he might have been, but he was a fierce competitor. He fought off injuries, even when his legs gave way, showing no fear in crashing a wall, going into the stands, or risking collision with another player chasing a ball. The Browns saw his determination in 1944. But what else might one expect of the slim outfielder who grandson Bryan recalled having written, “I’ll never give up on baseball.”

Notes

1 The Sporting News, April 1, 1978, 61.

2 Moore’s file in the Baseball Hall of Fame, no date.

3 “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1950, 4; “Lane Talks of Trades, Richards Adds Coach,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1950, 20.

4 Phone conversation with Bryan Moore, February 27, 2013.

5 All statistical data from either Baseball-reference.com or Retrosheet-org.

6 http://msgw.org/hinds/bible_anderson_askew.html (Family Bible of William Henry Anderson and Mary Ann Askew which records their births and the marriage of Gladys Maree Bryan).

7 “He Gets Around,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1936, 1.

8 “Cards Have Greatest Number of Outstanding Rookies in Major League Camps,” Hartford Courant, March 29, 1936, C3.

9 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 236-237.

10 “Moore’s 2 Homers Help Bees Triumph,” New York Times, May 2, 1936, 19.

11 Moore’s Hall of Fame file, May 21, 1936, no attribution available.

12 “Bees Topple Cards in Double-Header, New York Times, August 26, 1936, 24.

13 Phone conversation with Bryan Moore, February 27, 2013.

14 “Gene Moore Signs His Bees Contract,” Boston Globe, February 16, 1938, 22.

15 “Moore’s Home Run With Bases Full Defeats Giants,” Hartford Courant, April 21, 1938, 14.

16 “Bees Beat the Pirates and Take Third Place” and “Diamond Dots,” Boston Globe, May 20, 1938, 27.

17 “MacFayden Is to Pitch Today,” Boston Globe, May 21, 1938, 5.

18 “Bill Lee to Try for 5th in Row Against Bees,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 28.

19 “Vander Meer Joins the Hall of Fame, Boston Globe, June 12, 1938, C25.

20 “Bees May Lose Moore, Operation Seems Likely,” Boston Globe, June 27, 1938, 7.

21 “Hutchinson Wins His First Starting Game,” Boston Globe, July3, 1938, B5.

22 “Cubs Sweep Bees’ Series: Win in Ninth, 7-6, Chicago Daily Tribune, July 19, 1938, 15.

23 “Bees Lose Gene Moore for Balance of Season,” Boston Globe, July 26, 1938, 7.

24 “Big Boston Sox Deal Said to be “in the Bag,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1938, 10.

25 “Dodgers Get More Power in Moore,” The Sporting News, December 22, 1938, 2.

26 “Gene Moore News Welcome, Montreal Wants More Like It,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1942, 3.

27 “McCarthy Applies Skids to Snuffy Stirnweiss Bids,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1943, 18.

28 “Senators Need Knuckler Receiver; Get Ferrell Back,” Boston Globe, March 2, 1944, 9.

29 “Nat Outfield Crippled by Forced Deal,” The Washington Post, March 29, 1944, 12.

30 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1978, 61.

31 William Mead, Even the Browns, the Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties, (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978), 19.

32 Kaese, The Boston Braves, 237.

33 David Alan Heller, As Good As It Got: The 1944 St. Louis Browns, (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003), 53.

34 Bill Borst, The Best of Seasons: The 1944 St. Louis Cardinals and St. Louis Browns, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland), 1995.

35 Borst, 99.

36 “St. Louis Shortstop Aces Demand Hike in Antes,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1946, 16.

37 “Gene Moore Is Sold to Toledo Ball Club,” Hartford Courant, January 1, 1947, 13.

38 “Major flashes,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1947,” 20.

39 Phone conversation with Bryan Moore, February 27, 2013.

40 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1948, 29; phone conversation with Bryan Moore, February 27, 2013.

41 Phone conversations with Martha Moore, February 26, 2013, and Bryan Moore, February 27 and March 21, 2013.

Full Name

Eugene Moore

Born

August 26, 1909 at Lancaster, TX (USA)

Died

March 12, 1978 at Jackson, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.