George Hogreiver

In 1900 Sporting Life called George Hogreiver “the very best base runner in the profession.”1 “Hoggie” stole 948 bases in the minors, more than anyone else in minor-league history, and he stole 48 more bases in two major-league seasons. Like Ty Cobb, he was a daring, hyperaggressive baserunner. “Daring, yet careful,” said the Des Moines (Iowa) Register in 1905. Hogreiver “has the art and science of base stealing down to perfection.”2

In 1900 Sporting Life called George Hogreiver “the very best base runner in the profession.”1 “Hoggie” stole 948 bases in the minors, more than anyone else in minor-league history, and he stole 48 more bases in two major-league seasons. Like Ty Cobb, he was a daring, hyperaggressive baserunner. “Daring, yet careful,” said the Des Moines (Iowa) Register in 1905. Hogreiver “has the art and science of base stealing down to perfection.”2

An ideal leadoff man, Hogreiver was a patient hitter, willing to take a base on balls to get aboard. And he was an outstanding defensive outfielder, skilled at catching fly balls in the glaring sun. In a career that spanned a quarter of a century, he helped his teams finish in first place in 10 seasons.3

Hogreiver was brash, belligerent, and irrepressible. As the Register put it, “On the field he is all fight, spice and pepper.”4 Off the field he was a “very sociable chap” and a gentleman.5 “George is one of the best fellows to meet off the field you ever saw,” said teammate Bill Shipke. “When you get into the game, though, he would break your leg to win.”6

During his career, George’s surname was spelled alternately as “Hogreiver” and “Hogriever,” more often the latter, and baseball record books list him as “Hogriever.” But George spelled it “Hogreiver,” and that is the way it appears in Social Security and US Census records and on his tombstone.7 He was of German ancestry, his surname derived from the German “Hogrefe.”

George was born on March 17, 1869, in Cincinnati, the youngest of the six children of his parents, Frank and Caroline.8 Frank worked as a cigar maker. George survived a bout with smallpox as a child, probably during the epidemic that struck Cincinnati in 1881. The affliction left him with scars on his face.

In his late teens, George worked as a shoemaker,9 but what he really wanted to do was play baseball. He played on amateur teams in Cincinnati and got his first professional experience in 1888 and 1889 on the Hamilton (Ohio) club. In 1890 he hit .289 for the Ottumwa (Iowa) team,10 which won the pennant in the Illinois-Iowa League, and he was signed that fall by the Kansas City Blues of the Western Association.

Hogreiver stood 5-feet-8 and weighed 160 pounds, and he batted and threw right-handed. At the beginning of his career, his strengths were his speed and defense. In 1891 he made “some phenomenal plays in the outfield” for the Blues,11 but the team released him in June after he hit only .147 in 18 games. He finished the year with the Appleton Papermakers of the Wisconsin State League, batting .255 in 60 games with 47 stolen bases.12 Against the Oshkosh team on July 2, 1891, he wowed the Appleton fans when he “jumped up on the fence and caught a fly ball, thereby cutting off a home run.”13 The next season, in the Western League, he again shined in the outfield but hit only .194. He began the season on the St. Paul (Minnesota) club, which relocated to Fort Wayne (Indiana) in May and disbanded in July,14 and he finished the year on the Oshkosh Indians of the Wisconsin-Michigan League.

In 1893 Hogreiver blossomed as a hitter, batting .304 in 60 games for the Birmingham (Alabama) club of the Southern League. He left the team in July and went home to Cincinnati, and in late July he filled in as the umpire in three major-league home games played by the Cincinnati Reds. Hogreiver resumed his playing career in August on the Easton team of the Pennsylvania State League and helped the club finish in first place. In 18 games for Easton, he batted .380. On August 18, 1893, his home run to deep left field in the 15th inning gave Easton a 3-2 triumph over Harrisburg.15 And on September 6, he went 3-for-4 with five stolen bases and four runs scored in Easton’s 17-4 rout of Allentown.16

The next year Hogreiver helped the Sioux City (Iowa) Cornhuskers win the Western League pennant. His offensive numbers were eye-popping: a .350 batting average with 27 triples, 20 home runs, 171 runs scored, and a league-leading 93 stolen bases. He stole five bases and scored five runs against Detroit on May 26, and he clouted a double and two home runs against Grand Rapids (Michigan) on August 4.17

But Hogreiver’s misbehavior was also on the rise. He was accused of trying to kick one player and of deliberately spiking another,18 and was thrown out of several games. In an exhibition game at Nashville, his foul language prompted a local newspaper to declare, “A more objectionable ball player than he was never seen in Nashville.”19 And while on the coaching line in Indianapolis on September 21, 1894, Hogreiver got too “personal” in his remarks to umpire Jack Sheridan:

“Sheridan sent him to the bench in the third, but in the fourth he bobbed up again on the line and refused to come in at Sheridan’s command. The umpire fined him $10 and removed him from the game. He tried to go to bat in the fifth, but was stopped by Sheridan. There was some hot talk. …”20

The Cincinnati Reds acquired Hogreiver before the 1895 season, and Billy Earle, his manager at Birmingham, predicted success for him. Hogreiver “is the hardest worker I ever saw in my life,” he said and added, “He will make all the catchers earn their salary.”21

Hogreiver went hitless but scored a run in his major-league debut on April 24, 1895, in Cincinnati.22 The next day he got his first major-league hit, an RBI single off Bill Hart of the Pittsburgh Pirates.23 On May 9, Hogreiver went 3-for-4 with three stolen bases against the Brooklyn Grooms, and on May 21, he collected two singles and a double off Kid Nichols, the ace of the Boston Beaneaters.24 Facing the Beaneaters’ Jim Sullivan on June 4, Hogreiver slugged his first major-league home run, over the left-field fence in Boston.25

“Hoggie has made thousands of admirers by his sensational fielding, his magnificent base-running and his scrappy way of playing the game,” reported the Cincinnati Enquirer.26 But not everyone was impressed. Sporting Life chided him for his foul language and for “making a speech to the umpires every time he strikes out.”27

Hogreiver loved to sass Chris Von der Ahe, the St. Louis Browns’ owner, which caused Von der Ahe to go berserk and demand that the umpire eject Hogreiver from the game. One time, after a foul ball left the St. Louis ballpark, the umpire called for a new ball and Hogreiver shouted, “Come on Chris, come on with that dollar and a quarter.” The crowd roared with delight, knowing of Von der Ahe’s miserly reputation.28

Louisville pitcher Bert Cunningham was Hogreiver’s target on June 27. As Hogreiver stood at the plate, he taunted Cunningham and told him he was incapable of throwing a strike, and the tactic seemed to work as Hogreiver drew two bases on balls from the hurler. But later in the game, Cunningham picked off Hogreiver and “returned the laugh with interest.”29

Hogreiver performed well for the Reds, but the team had a surplus of outfielders, and in July he was farmed out to the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League. He had stolen 41 bases in 69 games for the Reds, but his .272 batting average was considered weak. The league average that year was .296, and outfielders were expected to exceed it.30 Hogreiver batted .417 and stole 30 bases in 46 games for the Hoosiers and helped them win the 1895 Western League pennant.

Over the next five seasons, Hogreiver was a spark plug atop the Indianapolis batting order, averaging 51 stolen bases and 126 runs scored per season.31 The team won the pennant in 1897 and 1899, and finished in second place in 1896 and 1898, and third place in 1900. Scout Ted Sullivan said Hogreiver was the best outfielder in the league.32 He played right field, the difficult “sun field” in Indianapolis, and Sporting Life said, “There is no outfielder in the Western League who can play in the sun field like Hogreiver.”33

On June 11, 1899, Hogreiver made a shrewd defensive play against the St. Paul Saints. With two outs in the bottom of the ninth and the score tied, the Saints had runners on first and third when Eddie Burke lined a single to right field. Chauncey Fisher, the runner on first base, was so thrilled that he went to congratulate Burke, while the runner on third base, Harry Spies, came home with the apparent winning run. Hogreiver, though, fielded Burke’s hit and alertly ran to the infield and touched second base for a force out of Fisher, thereby erasing the run scored by Spies.34 The game ended in a tie. Nine years later, against the Chicago Cubs, Fred Merkle of the New York Giants infamously repeated Fisher’s blunder.

On September 13, 1897, Hogreiver had a stellar offensive day, going 6-for-8 and scoring eight runs in a doubleheader against Grand Rapids.35 Because of his ability to draw walks, he sometimes scored more runs than he had hits. For example, against the Detroit Tigers on May 7, 1899, he went 2-for-2 and scored five runs.36 Tigers pitcher Bill Hill praised his patience at the plate:

“I know that one of the Detroit pitchers went into the box with the intention of either driving him away from the plate or hitting him in the head, but he could not force him back an inch. Hogreiver stood pat, and this man had to pitch to him or let him walk every time he came to the bat. He is the best waiter I have ever seen, and will get his base every time he faces a pitcher whose control is not perfect.”37

Hogreiver’s ever-present threat to steal added more pressure on the opposing battery. “It makes a pitcher sore to give me a base on balls,” he said, “and I get at him right away [by attempting to steal second base]. I also try and jolly the catcher, so that he will be trying to throw the ball to second before he has caught it himself.”38

While many of Hogreiver’s steals were predictable, he mixed in some unpredictable attempts. On July 29, 1896, he stole third base while St. Paul pitcher Tony Mullane held the ball. Catcher Harry Spies hollered to Mullane after Hogreiver took off from second base. Mullane “turned to throw to second, but found Hogreiver nearing third, so made no attempt to catch him.”39

Hogreiver stole home on July 12, 1897, “right under the nose” of Detroit Tigers pitcher Dad Clarkson; catcher Mike Trost dropped Clarkson’s throw home.40 And on July 16, 1898, Hogreiver stole home in the bottom of the ninth inning against the Kansas City Blues. He took off from third base, and Blues pitcher Elmer Meredith “became rattled and threw wild to third, while Hogreiver scampered across the plate with the tieing run.”41

In the second game of a doubleheader against the St. Paul Saints on September 4, 1897, Hogreiver demonstrated why Sporting Life called him “one of the dirtiest ball players in the League.”42 He came to bat in the second inning with two outs and runners on second and third:

Hogreiver “was furious when he popped up an easy foul to [Harry] Spies. As the St. Paul catcher started for the ball, Hogreiver, in great anger, spiked him on the heel. Spies caught the ball, and turning threw it with great force, striking Hogreiver in the ribs. The Hoosier right fielder retaliated with a vicious crack of his bat across Spies’ legs, knocking him over. Spies made for Hogreiver and they were engaged in a furious fight in no time.”43

In a spring exhibition game against the Reds in Cincinnati in 1898, Hogreiver was at his worst:

“Not a decision was made [by the umpire] that Hoggie did not question. In most instances Hogreiver’s protests were ridiculous. He left himself open for a little good-natured kidding from the stands. The occupants of the pavilion took a perfect delight in ‘handing out a few’ to the Hoosiers’ right fielder. … Finally, when [Indianapolis] Pitcher [Joe] Kostal made a wild throw, Hogreiver had to go over near the pavilion to get it. Then the pavilionites warmed to their work. They fired all kinds of cries at Hogreiver. The latter flew off the handle. He grabbed the ball and sent the sphere at the head of the spectators with all the force he could command. The ball player also used some very forcible and far from elegant language to the spectators. … Hoggie is a fine ball player, but he should curb his temper.”44

The teams played again the next day, and a subdued Hogreiver “behaved very nicely and proved that he can be a gentleman if he wants to.”45 On June 24, 1900, the “bad boy” impressed the Detroit Free Press with his good behavior in Detroit:

“Hogreiver is not only an able and conscientious ball player, who will take any chance to help his team out, but is a big hearted fellow as well. A small boy was overcome by heat yesterday and Hogreiver was one of the first to rush to his assistance and help carry the lad to a cool and shady place, where a physician attended to his wants.”46

Hogreiver’s sense of duty was also evident in front of a Kansas City hotel in 1896. A runaway horse “scattered the guests right and left” on the sidewalk; “Hogreiver heard the commotion, jumped out and caught the horse by the bridle” and stopped it.47

In 1901, the American League declared itself to be a major league, and Hogreiver received offers from representatives of three AL teams: John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles, Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics, and Charles Somers of the Cleveland Blues. But Hogreiver had already signed with Indianapolis and chose to honor the contract.48 However, after the Hoosiers disbanded in July, he signed with the last-place Milwaukee Brewers of the American League. His numbers for the Brewers were unimpressive — a .235 batting average and 7 stolen bases in 54 games — and he was released in mid-September with two weeks remaining in the season. It was his last opportunity to play in a major league.

For the next three seasons, Hogreiver played for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, and the 1902 Indians won the league championship. He was a prime favorite in Indianapolis. “The idol of the fans”49 made a sensational catch against the Columbus (Ohio) Senators on June 25, 1903:

“[John] McMakin hit a low, hard fly to right, which Hogreiver caught just before it kissed the grasses. He fell after the catch, but even then there was time enough to arise in all his splendor and throw to [second baseman Bill] Fox to double [Fred] Raymer, who had wandered too far from his hearthstone. It was a play decidedly Hogreiverish.”50

Hogreiver left Indianapolis when his contract was purchased in the spring of 1905 by Des Moines.51 He spent three years on the Des Moines club and helped it win consecutive Western League pennants in 1905 and 1906. He was twice runner-up for the league batting title, hitting .326 in 1905 and .319 in 1907.52 Remarkably, he stole 66 bases in 1906 at the age of 37, and he swiped 46 bases the following year.53

Filling in for injured players, the versatile Hogreiver often played in the Des Moines infield, especially at third base, and was even employed as the team’s catcher for a dozen games near the end of the 1906 season.54 He caught both games of a doubleheader in Denver on September 19, 1906. The weather that day was “bitterly cold and wet” and only 65 fans attended, as Des Moines and Denver split the twin bill.55 Pitching both games for Des Moines was 22-year-old Eddie Cicotte.

Hogreiver was traded before the 1908 season to the Western League’s Pueblo (Colorado) Indians, for whom he played second base and third base. He also managed the team at the beginning of the 1909 season. But he was suspended in June over a dispute with umpire Bob Glenalvin56 and was traded to the Lincoln (Nebraska) team, with whom he finished the season.

Lincoln released Hogreiver before the 1910 season, and he joined the Appleton Papermakers and helped them win the pennant in the Wisconsin-Illinois League in 1910. He was playing manager of the Papermakers in 1911 and 1912. Against the Oshkosh Indians on July 5, 1912, he made a diving catch and fractured his left shoulder blade, and was sidelined for seven weeks.57 In the offseason he retired as a player at the age of 43. He umpired in the Wisconsin-Illinois League in 1913 and 1914, and in the Wisconsin State League in 1923 and 1924.

Hogreiver married Wilhelmine “Minnie” Myse of Wisconsin in 1894, and they resided in Appleton. For four decades he was employed as the steward of the Appleton Elks Club, until his retirement in 1951. On January 26, 1961, he died in Appleton at the age of 91.

Hogreiver “played the game as though it were a battle, as indeed it was, as far as he was concerned, and reveled in the joy of combat. The umpire was never right when he called George out, nor was George ever known to have had, from his own point of view, a ‘legal’ strike called on him. … He had a good deal more than ‘pep,’ for his great gift or endowment was a fighting spirit.”

— Indianapolis News, September 7, 1923

“Hogreiver was the greatest minor-league player of his time.”58

— Bill Watkins, Hogreiver’s manager for nine seasons

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and checked for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

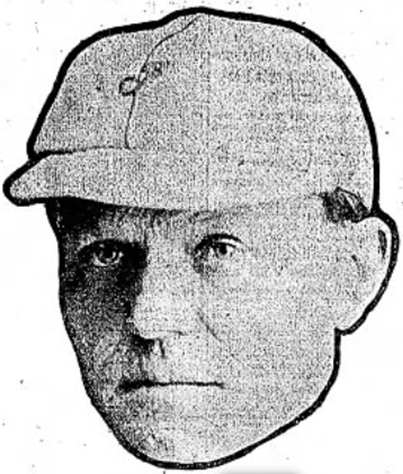

Photo credit: Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1904

Notes

1 Sporting Life, January 13, 1900.

2 Des Moines (Iowa) Register, April 2, 1905.

3 George Hogreiver played on 10 first-place teams: Ottumwa (Iowa), Illinois-Iowa League, 1890; Easton, Pennsylvania State League, 1893; Sioux City (Iowa), Western League, 1894; Indianapolis, Western League, 1895, 1897, and 1899; Indianapolis, American Association, 1902; Des Moines, Western League, 1905 and 1906; and Appleton (Wisconsin), Wisconsin-Illinois League, 1910.

4 Des Moines Register, January 19, 1908.

5 Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening News, July 22, 1907.

6 Lincoln (Nebraska) Daily News, June 15, 1912.

7 Ancestry.com and findagrave.com.

8 The family surname is spelled “Hograver” in the 1880 US Census.

9 1885 and 1887 Cincinnati city directories.

10 Sporting Life, December 20, 1890.

11 Sporting Life, May 9, 1891.

12 National Baseball Hall of Fame file.

13 Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Northwestern, July 3, 1891.

15 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 19, 1893.

16 Sporting Life, September 16, 1893.

17 Sporting Life, June 2, 1894; Detroit Free Press, August 5, 1894.

18 Indianapolis Journal, June 13, 1894; Kansas City Gazette, August 27, 1894.

19 Quote from the Nashville American reprinted in the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, April 3, 1894.

20 Indianapolis Journal, September 22, 1894.

21 Cincinnati Enquirer, March 26, 1895.

22 Sporting Life, May 4, 1895.

23 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 26, 1895.

24 Sporting Life, May 18 and June 1, 1895.

25 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 5, 1895.

26 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 30, 1895.

27 Sporting Life, May 18 and July 13, 1895.

28 J. Thomas Hetrick, Chris Von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999), 174.

29 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 28, 1895.

30 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 23, 1895; Sporting Life, August 3, 1895.

31 Hall of Fame file.

32 Sporting Life, August 25, 1900.

33 Sporting Life, January 4, 1896.

34 Indianapolis News, June 12, 1899.

35 Sporting Life, September 25, 1897.

36 Sporting Life, May 27, 1899.

37 Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 15, 1900.

38 Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, December 15, 1900.

39 Indianapolis Journal, July 30, 1896.

40 Detroit Free Press, July 13, 1897.

41 Indianapolis News, July 18, 1898.

42 Sporting Life, October 1, 1898.

43 Logansport (Indiana) Pharos-Tribune, September 6, 1897.

44 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15, 1898.

45 Hamilton (Ohio) Journal News, April 13, 1898.

46 Detroit Free Press, June 25, 1900.

47 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, May 24, 1896.

48 Indianapolis News, March 11 and April 2, 1901.

49 Indianapolis Journal, April 21, 1904.

50 Indianapolis Star, June 26, 1903.

51 Sporting Life, March 25, 1905.

52 Sporting Life, March 31, 1906; Des Moines Register, November 29, 1907.

53 Hall of Fame file.

54 Sporting Life, January 5, 1907.

55 Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, September 20, 1906.

56 Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, June 15, 1909.

57 Oshkosh Northwestern, July 6 and August 22, 1912.

58 Indianapolis News, June 7, 1913.

Full Name

George C. Hogreiver

Born

March 17, 1869 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

January 26, 1961 at Appleton, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.