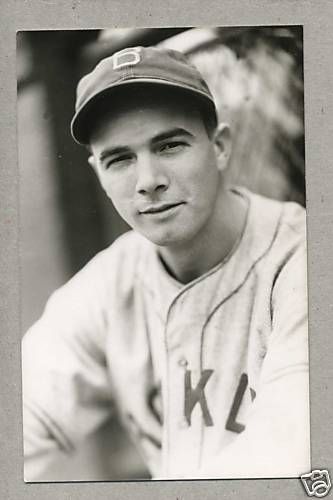

George Jeffcoat

George Edward Jeffcoat, the older of two brothers who played in the majors, spent two full seasons and parts of another two others pitching in the National League. He had a record of 7 wins and 11 losses in 70 appearances between 1936-43 with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. After his playing days, he was ordained as a Baptist minister and served as a church pastor for 17 years.

George Edward Jeffcoat, the older of two brothers who played in the majors, spent two full seasons and parts of another two others pitching in the National League. He had a record of 7 wins and 11 losses in 70 appearances between 1936-43 with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. After his playing days, he was ordained as a Baptist minister and served as a church pastor for 17 years.

Jeffcoat was born on December 24, 1913, in New Brookland, South Carolina, one of four sons and a daughter born to Alma (Bundrick) and George McCoy Jeffcoat.1 The Jeffcoat side of the family was of English descent. His father, a security guard at the cotton mill in nearby Columbia, began teaching his sons to play baseball by the time each turned 5 years old.2 All four Jeffcoat boys played for the Columbia Mills Ducks semipro team, and all four were signed by major league organizations. George and his brother Bill led the Brookland-Cayce High School baseball team to the 1933 state championship.3

George’s mother died in a traffic accident when he was in his late teens and already recognized as a pitching prospect.4 His father died in 1944.

Even as his professional career was developing during the depth of the Depression, George had to support two of his younger siblings. Hal Jeffcoat, nearly 11 years younger than George, and their sister Nellie moved in with George after spending two years in a North Carolina orphanage.5

After graduating from high school and a stint with the Columbia Mills team, Jeffcoat briefly attended the University of South Carolina, but he left to marry the former Annie L. Jones in January 1934 and to sign a contract early in 1935 with Dodgers scout Blackie Carter. The first of George and Annie’s two children, Sara Jane, was born in 1935; their son George Jr., was born in 1938.6

A right-hander who relied primarily on an excellent curve ball, Jeffcoat stood 5-foot-11 and weighed between 175 and 180 during his playing days. The Dodgers assigned Jeffcoat to the Leaksville, North Carolina, farm team in the Class D Bi-State League. His professional career started off in fine fashion there: he won 20 games and averaged a strikeout an inning.

New York Giants Hall of Famer Bill Terry, who visited Columbia on the recommendation of scouts who touted the young pitcher, actually had intended to sign George in the winter of 1934. He “came to the cotton mill where my dad and I worked,” Jeffcoat recalled in 1938. “Everybody knew who he was. Work practically stopped. Everybody jammed into the office to ask him questions and get his autograph.”

“This is George,” Jeffcoat’s father told Terry. “Then I’ve got another boy, Bill, who is also a pitcher. Which one did you want to see?” Terry looked at George, who at that point weighed about 145 pounds. “Bill’s my man,” said Terry. Just 17, Bill Jeffcoat, already six feet tall and 175 pounds, had to be excused from high school to see the famous Giant. “They made the deal right there,” George Jeffcoat told Tommy Holmes of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Bill’s father signed the contract for him and accepted his $2,500 bonus. During the 1936 season, as George was beating the Giants, Terry sent word to Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel : “You’re a lucky stiff because I took the wrong Jeffcoat.”7

Jumping all the way from Class D, George had made his major league debut at age 22 on April 20, 1936, with the Dodgers, going on to appear in . 40 games on a pitching staff dominated by players in their 30s. After spraining an ankle in July that year, Jeffcoat was on crutches and missed several weeks. The injury came at an inopportune time because he had become “the crack relief hurler on the team,” Holmes, the Dodgers correspondent, wrote in The Sporting News. “A slender right-handed performer with a sparkling curve-ball delivery, Jeffcoat was making good with a bang.”8

Burleigh Grimes took over from Stengel in 1937 and began working with Jeffcoat to sharpen his control. And his performance improved enough as the season progressed that Grimes gave him his first start in six weeks. George responded by shutting out the Pittsburgh Pirates on four hits on July 21. The complete game, his lone major league shutout, was the sixth time he had pitched in eight days.9 But his season was derailed the next day by an attack of appendicitis. After his appendix was removed, he was sent home for the rest of the season.10

Beset by arm trouble, Jeffcoat was sent to the minors in 1938. Shipped to Kansas City, he threw just three innings in two games all year. Back with the Dodgers early in 1939, he pitched two shutout innings on opening day. It was to be his last appearance for the Dodgers. He wore uniform number 42 that day, the last Brooklyn player to wear 42 until Jackie Robinson in 1947.

After he was sold to the Nashville Vols on May 10, Jeffcoat told a teammate, “I’m going to pitch my way back to the majors,” Red O’Donnell reported for The Sporting News. But he ended up pitching the next four seasons for Nashville in the Southern Association. He went 14-6 with the 1940 Nashville Vols, a squad listed on Minor League Baseball’s web site as the minors’ 47th best team of the 20th century. Jeffcoat set a league record on September 10 in the playoffs that year by striking out 18 batters, including seven in a row, against Chattanooga. From the third to the seven inning of that game, he struck out 14 of 19 batters. He went 13-12 in 1941 and again in ’42. 11 (Before delivering this record performance, Jeffcoat had predicted what was to come. “I believe I’ve got as good a curve as any of them” in the majors, Jeffcoat told a group of reporters in a pre-game interview, “and I’m going to show you something.” And then he did.) 12

Jeffcoat, a favorite of Nashville’s longtime owner and manager Larry Gilbert (who listed him as one of the pitchers on his all-time Nashville team), was the opening day starter for the Volunteers three straight years, 1940-42. He got the nod over his soon-to-be much more famous teammate, Johnny Sain, in the latter two years.13

In the fall of 1941, Jeffcoat found work as a plumber’s helper.14 No doubt the pay was helpful, too, for a minor leaguer with a wife and two children.

Jeffcoat led the Southern Association in strikeouts in the 1942 season. He had finished one behind the leader, teammate Ace Adams, in 1940. His earned run averages during the Nashville years (never lower than 4.48) were undoubtedly inflated by the short right field fence—282 feet from home plate—in Sulpher Del, the Vols home park. He had pitched one of just three shutouts there in 1939.15

Sold to the Boston Braves, where Stengel was now managing, at the end of the 1942 season, Jeffcoat was counted on to bolster a staff left shorthanded by the draft. “He was the best curve-ball pitcher in the Southern Association last year,” Gilbert said in March 1943, touting Jeffcoat’s chances. “He is still a young fellow and has plenty of years before him.” 16

Indeed, Jeffcoat made the big league team that spring. Still just 30, he did well enough as a short man out of the bullpen—17.2 innings over eight games, but he found himself back in the minors by July. His final big league appearance came on June 20, 1943 when he pitched a perfect top of the ninth against the Phillies in a 7-0 loss. He finished the season with the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association.

Wartime regulations likely kept Jeffcoat out of professional ball in 1944. He had taken an off-season job as a lineman with the telephone company in Charleston, South Carolina, and the wartime rules prevented him from leaving that employment while the war continued. So Jeffcoat’s only baseball that summer was with a Charleston city sandlot team.17

The following year Jeffcoat was back with Indianapolis where he pitched well enough against (and for) still war-depleted rosters. Three of his seven victories were shutouts, and his 3.63 ERA was more than a run lower than his lifetime figure in the minors. He gave it one more shot in 1946 playing for Tulsa and then Shreveport in the Texas League. Not too successfully though: he lost 14 of 18 decisions and was carrying a 5.35 ERA before he was released. He returned to Larry Gilbert in Nashville, where his brother Hal would play briefly that season, before hanging up his spikes for good.

Hal Jeffcoat was just starting a career in which he would play as an outfielder for six seasons with the Chicago Cubs before switching to pitching and spending another six-plus seasons on the mound with the Cubs, Cincinnati Reds, and St. Louis Cardinals. His brother George was instrumental in getting Hal his first professional tryout. George Jeffcoat sent a telegram to Vols manager Gilbert at the end of the war, saying he had a kid brother who “would be a great pitcher when he got out of the army.” Gilbert assumed that the younger Jeffcoat was indeed a pitcher, but when he showed up at the Vols camp in Macon, Georgia, in the spring of 1946, Hal told Gilbert that he played center field.18

George’s brothers, Charley and Bill, both pitched in the minor leagues. Charley was signed by the Yankees. His nephew, Hal’s son Harold, also pitched in the minors in the San Francisco Giants system before becoming a college president.

In 1953, George Jeffcoat was a founding member of Cayce Masonic Lodge 384 near his home in South Carolina. By September of that year, he had enrolled in the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary after being licensed to preach by the State Street Baptist Church in Cayce. He graduated from the seminary in 1955. After ordination, he was briefly assigned to missionary work before serving for 17 years as the pastor of the Old Lexington Baptist Church in Leesville, South Carolina.19

Jeffcoat, age 64, died in Leesville on October 13, 1978 from what the Lexington County coroner determined was an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound.20 According to authors Frank Russo and Gene Racz in Bury My Heart at Cooperstown: Salacious, Sad, and Surreal Deaths in the History of Baseball, “he inexplicably and unexpectedly shot himself to death in his home…. there was some suspicion that he may have been in ill health.”21

George Jeffcoat is buried in Old Lexington Baptist Cemetery in Leesville. His wife, who died in 1999, is buried next to him, while their son, George “Eddie” Jeffcoat, who died in 2004, is buried nearby.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Harold G. and John P. Jeffcoat, George’s nephews (his brother Hal’s kids), with this piece.

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 New Brookland, now an historic district in West Columbia, S.C., was a planned community built between 1894 and 1916 to house the families of workers at the Columbia Mills cotton plant.

2 Telephone conversation, John P. Jeffcoat with author, February 17, 2017.

3 Tommy Holmes, “Jeffcoat Brothers May Meet as Rival Hurlers On Dodgers, Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 26, 1936, 56.

4 Emails, Harold G. Jeffcoat to/from author, Feb. 21-23, 2017, in author’s possession.

5 John P. Jeffcoat, telephone conversation.

6 Holmes, “Jeffcoat Brothers May Meet.”

7 Holmes, “Looks Deceived Terry and He Got the Wrong Jeffcoat,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 20, 1938: 39.

8 Holmes, “Dodgers Can’t Dodge Trouble; Now They’re Short On Pitching,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1936, 1.

9 Holmes, “All Work and No Play Makes Jeffcoat Hot Hurler,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 22, 1937, 19.

10 “Jeffcoat to Undergo Appendix Operation,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 5, 1937: 40.

11 Red O’Donnell, “George Jeffcoat Makes Good on a Promise,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1943, 5; Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, www.milb.com/milb/history/top100jsp?idx+47.

12 Raymond Johnson, “Jeffcoat Likely October Draftee,” Nashville Tennessean, September 12, 1940, 14.

13 O’Donnell, “George Jeffcoat Makes Good.”

14 Johnson “Most of Vols Hope to Get Defense Jobs for Winter,” September 10, 1942, 10.

15 Johnson, “Dell Toughest Ball Park in League, Hurlers Say,” ibid., July 9, 1941, 10.

16 O’Donnell, “George Jeffcoat Makes Good.”

1717 Johnson, “Jeffcoat Sandlotter,” Nashville Tennessean, July 20, 1944, 15.

18 Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion”, June 15, 1947, 45. George’s nephew, Harold G. Jeffcoat, recalled a story, perhaps apocryphal, that his father Hal liked to tell about Hal’s return home from the war. George had apparently received word that Hal, a paratrooper, was missing and presumed killed in action. When George saw Hal walking up to the door of his South Carolina home, he thought he was seeing a ghost. See note 4.

19 “Case Lodge History,” http://www.mastermason.com/cayce384/history.htm; “George Jeffcoat Trains for Ministry,” Nashville Tennessean, September 2, 1953, 17. The New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary admissions office confirmed Jeffcoat’s graduation in a telephone conversation with the author on February 24, 2017.

20 Obituary, The Sporting News, November 4, 1978, 57.

21 Frank Russo and Gene Racz, Bury My Heart at Cooperstown, Salacious, Sad and Surreal Deaths in the History of Baseball (Triumph Books, Chicago, 2006), excerpt at Google Books website, http://bit.ly/2qmUpZf.

Full Name

George Edward Jeffcoat

Born

December 24, 1913 at New Brookfield, SC (USA)

Died

October 13, 1978 at Leesville, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.