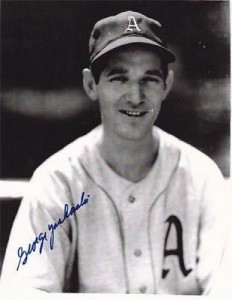

George Yankowski

At the end of the 2019 baseball season, 25 former major-league baseball players who had seen military service in World War II survived.

At the end of the 2019 baseball season, 25 former major-league baseball players who had seen military service in World War II survived.

One of them was Massachusetts native George Edward Yankowski, who served in the United States Army and saw combat with General George S. Patton’s Third Army. At age 96, this ex-catcher said he’d never forget his wartime encounters with legends like Babe Ruth if he lived to be 100. Based on his active lifestyle, he made it to 97.

Yankowski played in parts of two seasons in the majors — 1942 with the Philadelphia Athletics and 1949 with the Chicago White Sox. He worked behind the plate in six games for the Athletics and in six more with the White Sox, also appearing in another six games as a pinch-hitter.

His first games in professional baseball were those six for Philadelphia, at age 19. The first time he played minor-league ball was almost four years later, after the war.

He got a base hit in the first game he started for Connie Mack‘s A’s, but his career batting average was just .161. He drove in two runs for both the A’s and White Sox. In 35 fielding chances he never committed an error.

George was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on November 19, 1922, to Polish immigrants Voslov and Stefania (Tokarski) Yankowski. Voslov worked as a tool and die maker, and a machinist for Hood Rubber Company in Watertown, Massachusetts, which became B.F. Goodrich. The family lived in Watertown and had six children: Ida, Edith, Victor, George, Elizabeth, and Robert.

“I was an outstanding first baseman as well as an exceptional basketball player at the West Junior High School in Watertown,” Yankowski recalled in 2019. “I went to Watertown High and tried out for the baseball team. I did not make either varsity or J.V. My sophomore year I was so-so in basketball and I blossomed in my junior year. A new coach had come to Watertown, Mr. Dan Sullivan. I once again in the spring tried out for baseball. I made the varsity as a catcher.”1

“At the age of 15, I couldn’t make the J.V. squad. At the age of 16, I was the best high school catcher in the state.”2 Catching was never easy; George had his front teeth knocked out by a baseball bat. He batted and threw right-handed, and grew to an even six feet tall, listed with a playing weight of 180.

When the regular catcher graduated, Coach Sullivan chose Yankowski, who he described as “a big boy who was some shakes on the basket-ball five,” to replace him.3

“I brought my first baseman’s glove to the first day of practice, but coach Sullivan looked at me and threw a catcher’s mitt at me and said, ‘Here, you’re a catcher.’” Sullivan was tough, too. When George had his front teeth knocked out, Sullivan took him to the dentist — but only four innings later. Dick Berardino, later a coach with the Boston Red Sox, said, “Coach Sullivan wanted him to finish the game first. He had four teeth in his locker during the last four innings of that game.”4 George recalled that Sullivan told the dentist “to do a good job because I reminded him of Mickey Cochrane. Wow, when I heard that I was thrilled.”5

By early May, he’d already begun to prove himself. A May 2 story said, “George Yankowski, the Watertown receiver, is credited for a great deal of the team’s success by Coach Dan Sullivan…A newcomer this season, Yankowski has proven a very capable handler of pitchers.”6 A fortnight later, another Globe reporter called him a “find” and wrote that he “has a nice arm and a nice eye at the plate.”7 He was batting close to .600 by the end of the month. By the end of June, George had been named captain of the Watertown High baseball team for the coming year. His batting average for the season was .505 and he drove in 36 runs. With just six errors in 213 chances, he led the team in fielding as well.8 Watertown High “went all the way to the Eastern Mass final before bowing to Norwood at Fenway Park.”9 The Boston Post named him an all-scholastic player.

George was president of both his junior and senior classes at Watertown High. He graduated in 1940 and then attended Northeastern University, where he studied industrial management.

In the spring of 1941, Yankowski caught for Northeastern’s freshman team. He moved up to the varsity in 1942; his name was often abbreviated in box scores (with some variations) as “Y’k’wski.”10 The Huskies won that year’s regional intercollegiate championship.

After the 1942 college season ended, Yankowski played for a number of semipro teams, including Woonsocket in the New England League. A 1944 article noted that he had played for Berlin, New Hampshire, in the semipro Northern League in the summer of 1939, and then Lancaster, New Hampshire, the next two summers.11

Unsurprisingly, scouts had noted him, among them the Yankees’ Paul Krichell. In July, he was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics, though it was written that he “had been eyed covetously by the [Boston Red] Sox.”12 In a 2019 interview, Yankowski named Tom Fleming as the scout who signed him.13 He told a writer that it had been “my chance to help myself the most,” adding that the “Athletics promised to keep me for the remainder of the year.” With the Yankees, or another team, he might have immediately been placed with a minor-league team. “I would not have signed with the Philadelphia club if I were going to be sent out.”14

Yankowski made his debut on August 17 in Philadelphia against the Yankees. The Boston Herald wrote, “It is, perhaps, the first time that a college sophomore has stepped into the big leagues without any minor league experience.”15 In that first game, he took over for Hal Wagner in a game the A’s were losing, 14-0, after five innings. He recalled to historian Anne R. Keene, “And who’s the first batter up? Joe DiMaggio. Wow. I hate to say this, but I called for a fast one. I wanted Joe to hit a home run. Isn’t that awful? [laughs] Can you imagine, a 19-year-old squatting there with Joe DiMaggio batting?”16

Yankowski came up to bat with two runners on base in the bottom of the sixth but grounded into an inning-ending double play. In the bottom of the ninth, he made the final out of the game.

He appeared briefly in two later August games. On September 2, 1942, the Indians were in Philadelphia and Yankowski came into the game early, after a first inning in which Cleveland scored eight runs off starter Herman Besse. He got his first base hit, an infield single to third base in the bottom of the ninth.

His first start came at Fenway Park on September 6, handling Bob Savage. “I was a Red Sox fan, 10- to 12-year-old kid. Knothole gang, all those years. You could watch the Red Sox for free on certain days. Now, [facing Charlie Wagner] I got up to bat for the first time [in Fenway] as a major leaguer. I hit a ball off that fence in left field, like a shot, for a double. Can you imagine that? Standing on second base, 19 years old, after that experience? On top of the world!”17

Savage singled to right; Yankowski was thrown out at the plate trying to score. In the fourth inning, he collected his first run batted in, scoring Bob Johnson on an infield groundout. In the sixth, he picked up another RBI, again on an infield groundout. The Red Sox held on to win, 8-7, with a Ted Williams solo home run in the bottom of the eighth making the difference.

The Athletics lost every one of the six games in which Yankowski took part. The team finished in last place, 48 games behind the first-place Yankees.

Yankowski returned to Northeastern for the fall semester. In November 1942 he married Geraldine Molito, his high school sweetheart. They were happily married for 40 years.

Yankowski signed a contract for 1943 with the A’s in February.18 He was seen as a third-string catcher behind Hal Wagner and Bob Swift. But he had enlisted in the Army Reserve in October 1942, and on April 24 he joined 128 others heading to Fort Devens, northwest of Boston. By early May, Private Yankowski was catching for the Fort Devens baseball team; he was soon hitting over .400.

On June 5, Fort Devens played the Boston Coast Guard at Boston’s Braves Field, winning 11-6. Skippy Roberge and Yankowski were on the victorious team. Cleveland Indians catcher Jim Hegan (from Lynn, Massachusetts) played for the Coast Guard.19

Yankowski’s most notable game in the service involved both Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. It came on July 12, 1943, at Fenway Park and was a benefit for underprivileged children, the Fifth Annual Mayor Tobin Field Day. The “Ruth All-Stars” — managed by Ruth himself — faced the Boston Braves. Among Ruth’s players were Williams in left field, Joe DiMaggio in center, and Gene Hermanski in right. Roberge played third base. Hegan, the starting catcher, doubled once in two at-bats. Yankowski took over behind the plate and came to bat in the seventh. The score was tied, 5-5, after six. After Williams’ three-run homer. Yankowski came up to bat with a runner on third base and drove in the team’s ninth run with a ball hit high off the left-field wall.20 The Braves scored three in the bottom of the seventh, so Yankowski’s RBI provided the margin of victory.

In Anne R. Keene’s 2018 interview, George expanded on the game (this version of the account is abridged):

“We had a pretty good team at Fort Devens. A few of us were invited to join the group of other professional baseball players like Ted Williams. Walt Dropo was on our Army team. It was kind of a thrill to play at Fenway Park. To me, it was one of the greatest experiences I ever had, because as a kid Babe Ruth was baseball, you know. He was it. And here we were playing on the same team. Of course, he was an older gentleman then.

“I had a chance to catch batting practice before the game with Williams and Ruth putting on a hitting exhibition. I was 20 years old at the time. That was a very thrilling moment for me. It was very exciting to be on the same squad with players like DiMaggio and Ted Williams. Jimmy Hegan caught the first part of the game. They put me in at the second half and I happened to get up with a runner on base. I hit a ball. I thought it was a pop fly to left field, so I kind of jogged. I only got a single.

“Babe Ruth was coaching first and came over to me and put his arm around me and with that husky voice he had at times said to me, ‘Nice going, Kid.’ Wow, what a thrill! I’ll never forget that if I live to be 100. Which I may.”21

Asked to expand more on his time in the service, he said, “That winter [later in 1943], I got a little itchy and decided I wanted to be a pilot. So, I joined the Army Air Corps. It was very difficult to become a pilot at that time because…I remember when we got to [the training camp], they told us that they didn’t need pilots anymore because we controlled the skies then. In Europe and Asia.” Hundreds of young men, most aged 18 or 19, were still allowed to take the tests. Yankowski was one of only three who qualified to become a pilot, navigator, or bombardier. “I was sitting on top of the world for a short while, waiting to go to Texas to become a fighter pilot. I could already see the wings on my chest.”22

That particular dream was not to be, he said. “However, at that time they needed soldiers in the ground forces because they were getting ready to invade Europe. Anybody that was an aviation cadet — like I was — or in the Army’s specialized training programs throughout the country — anybody that was sent back to the ground forces. That’s what they needed: infantry. I ended up as an infantry soldier in the 87th Division, Third Army.”23

By May 1944, Yankowski was stationed at Fort Jackson (South Carolina) with the 346th Infantry Regiment of the 87th Division. He was a catcher for the Invaders, one of three Fort Jackson baseball teams in the Servicemen’s Baseball League.24

Having to give up baseball to enter the Army hadn’t struck him as unusual. “Everybody … everybody was going in the service. To do their part. It seemed natural to be serving … to be in the service somewhere. There’s no resentment or anything like that. It was as natural as going to school…You’re going into the service to fight a war. I enjoyed playing baseball — thoroughly. I’d loved it as a kid. But looking back, really, baseball was — compared to the service and the war — was really almost next to nothing. Really.And for a while, we were losing. Hitler, Germany controlled all of Europe. And part of Africa. Japan, they owned the whole Pacific. England was on their knees. It really looked bad. Sports really became very insignificant in the scheme of things.”

The Third Army was under the command of Gen. George S. Patton. Pvt. Yankowski shipped out with the division on the Queen Elizabeth and arrived in Europe in October 1944, first landing in Scotland, then taking the train to England. After the troops crossed the Channel to France in November, Yankowski said, “Our division went into combat in Metz, France.” He became a sniper.

His survival was far from guaranteed. The division website explains: “They first entered combat in France’s Alsace-Lorraine, and after extremely bloody fighting, crossed the German border in the Saar, capturing the towns of Walsheim and Medelsheim. Caught up in the Third Army’s historic counterattack in the Battle of the Bulge, the 87th Division raced off into Belgium — attacking the German Panzer Lehr Division near Bastogne at the towns of Pironpre, Moircy, Bonnerue, and Tillet. … Soon after breaching the Siegfried Line in the Eifel Mountains, the division crossed the Moselle River and captured Koblenz. Then the Rhine River crossing near Boppard and the dash across Germany which took them to Plauen, near the Czech border.”25

In an understated comment, Yankowski says, “I saw a little combat in Europe.” He added, “Of course, two minutes in combat can be a lifetime. However, I was lucky enough to survive in combat from December until the first week of May. Including the Battle of the Bulge, which was a horrible, horrible winter. Besides getting shot at I had friends who are dead. Anyhow, somehow I was lucky enough to survive that. I did spend three months in the Army hospital with hepatitis. I survived and here I am, still playing golf once a week and still enjoying life.”

Yankowski served until after V-E Day in May 1945. Historian Keene, who’d done her research, noted, “I know you were decorated. You had a Bronze Star, a Combat Infantry Badge, and the French Legion of Honor award.”

Yankowski responded:

“I’m no hero. I’m kind of proud of the Combat Infantry Badge. I don’t know if that was true, but I read somewhere that that was General Eisenhower’s favorite medal. I’m kind of proud that I was able to get that. Being in combat as a foot soldier — any soldier — and facing fire from the enemy is bad. I happened to be a foot soldier, living in the dirt, and fighting. One of the worst things I ever heard in my whole life, standing on a cold hill in December waiting to attack the German Army. Nobody saying a word. Standing on the hill, a cold hill. And I heard the first sergeant say, ‘Fix bayonets!’

“I can’t tell you. I’m shivering! A cold feeling is coming over me right now. When he said, ‘Fix bayonets’ you know what that means. You’re going to be facing the enemy soldier with a bayonet. Hand-to-hand combat. It was very discouraging to me at that moment. ‘What the hell am I doing here? With bayonets. Are you kidding me?

“Snipers have a [telescope] on their rifle. You cannot attach a bayonet to a sniper’s rifle. The only thing I had was a knife that’s about eight inches long.

“I would say within the next couple of minutes, the sergeant called me over. He said, ‘George, would you mind carrying this weapon?’ In World War II, besides the Thompson machine gun — which was kind of a large thing — they made a machine gun that was similar to a grease gun that cleaned automobile wheels. In fact, they called it a grease gun because it was so cheaply made. It was a machine gun and you put a long clip in it. He said, ‘Do you mind carrying this?’ I draped that thing over my neck. From that moment, I felt like the happiest person on earth. I did have a chance to use it later on in the day.

“It’s a little bit mind-boggling to have that kind of luck. I can tell you what the sound of bullets is like, coming within six inches of your ear — I can tell you what they sound like. I heard bullets go by within six inches. I saw bullets landing eight or 10 inches in front of me. I’ve seen them, and heard them, and never felt them. And thank God.”26

The Battle of the Bulge was exceptionally bloody. American forces suffered more than 75,000 casualties.27 More than 19,000 Allied soldiers lost their lives.

Later in the September 2019 conversation, George explained the sound of a bullet going by one’s ear. He snapped his fingers.

Asked about being a sniper, he said, “The best thing we could do was to shoot an officer. If there was a group, we always tried to shoot the person in command. That was not too hard to figure out. When there was a group of enemy soldiers, and they’re at a distance — 500 or 600 yards away and all dressed alike — you can usually pick out the person in charge because [his] arms are moving. Talking.”28

“What a terrible thing a war is. Who fights wars? They are all young kids. Young kids dying…

“We were into Germany when the war ended. Near Czechoslovakia.” When victory was declared in Europe, it was a very happy day. “You can’t imagine. You can’t imagine. From December until May, we never held a company formation like they do in peacetime.” They were mired in deadly combat. Then came V-E Day. “We finally met in formation and they raised the American flag. I can’t tell you what a beautiful sight that was, to see that flag going up for the first time in all those months. The war was over. We won the war! How could you beat that? To see that flag going up was quite a sight.”29

With the German surrender, the European Theater was closed, but war was still raging in the Pacific. And George Yankowski was on tap to be sent there.

“We were one of the first divisions that was sent back to the United States, to get ready to invade Japan. Very shortly, we found ourselves on a ship headed for America.” They arrived in July 1945 and the division was sent to Fort Benning. “We got home early, which was kind of nice. We got a month off and while I was on furlough for that month, they dropped that bomb on Japan.”

Yankowski finished his Army service as a private first class. He joked, “God loved privates, because he made so many of them.”

After being mustered out, Yankowski rejoined the Athletics in time for spring training. He didn’t make the cut and was released on April 13, 1946. He joined the Fall River (MA) Indians and played for the next two seasons for the Class-B New England League team. It was independent in 1946 but had a working agreement with the Chicago White Sox in 1947. Yankowski showed up in the Boston newspapers occasionally, when performances merited it. One such day was May 19, 1946, when he went 6-for-9 in a doubleheader against the Portland (ME) Gulls. He was 3-for-5 against the Providence (RI) Chiefs on June 16. His ninth-inning sacrifice fly won another game against Providence on August 25. Appearing in 115 games in 1946, he hit .249; he bumped that up to .286 in 1947.

Yankowski had resumed his studies at Northeastern, majoring in Business Administration. He graduated in 1947 and added a Master’s degree from Boston University.

In 1948, Yankowski joined the Muskegon (MI) Clippers, a White Sox affiliate in the Class-A Central League. He played in 129 games and hit .285.

In 1949, he made the big-league team, appearing in an even dozen games in April, May, and June. He had three base hits in 18 plate appearances. He had one very good day, on June 25, against his former team, the Athletics, at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park. His sacrifice fly scored George Metkovich with the fourth of Chicago’s five first-inning runs. He doubled to left field to open the fourth, but was left stranded. In the top of the eighth, his single gave the White Sox a 6-5 lead. However, the Athletics won, 7-6.

In the second game of two on the following day, Yankowski called a 3-0 shutout. In relief of Bob Kuzava, Marino Pieretti worked the final two innings.

His final game in the majors was on June 28. On July 11, his contract was released to the Memphis Chickasaws in the Double-A Southern Association. Yankowski played out the season there, hitting .209 in 33 games. That was the end of professional baseball for him.

In the summer of 1950, he played for Milford in the semipro Blackstone Valley League. The following summer, he caught for the New England Hoboes; a photograph of him in a hobo outfit appears in the July 8, 1951, Globe.

In March 1950, Yankowski was appointed assistant baseball coach at Watertown High. He also taught “commercial and business subjects” there as a permanent substitute teacher. He became head coach in 1951.30 He coached for 15 years but relinquished that role upon becoming the school’s guidance counselor. He became head of the high school’s work-study program in the 1960s, working with potential dropouts.31 He retired from teaching in the early 1980s but still kept working.

In 1993, Yankowski was named to the Watertown High Athletic Hall of Fame. Dick Berardino (Class of 1955), whom Yankowski had coached, was also inducted that year. 32 Berardino (who played in the minors from 1958 through 1965) and Yankowski both taught business subjects in the same department at Watertown High. Their teaching careers overlapped for about 10 years.33 Berardino fondly remembers Yankowski as a coach: “He had a great way of making everyone feel comfortable. He wasn’t a yeller or a screamer, but he was very knowledgeable about the game…. He wanted to win but at the same time he displayed a witty personality. The one thing we all remember about him was that he made us laugh. He was an amazing storyteller.”34

In 2019, Yankowski’s second wife, Mary, told of how the two became a couple in the late 1990s. She was Mary Jones at the time (née Urquhart), a former special education teacher who worked in Watertown’s school system for 46 years. “We were both widowed. I’d been a widow for 12 years and George for 16 years. We were at a golf tournament for the Boys and Girls Clubs in Watertown. We were at the same table, and he asked me to play golf with him. I was going to Hong Kong the next day with a teacher friend. When we came back, he called me. We met for a half-hour for coffee at Starbucks, and he asked me out for dinner and dancing. I thought, ‘Oh! Someone who dances? I’ll go.’ That was in August 1998 and we were married in June 1999.”

She added, “When we got married, we moved to Lexington. We lived there for 12 years. In between, we came down here to visit The Villages. We were still both working. George worked until he was 85. He worked three days a week as a courier for ADP, delivering payroll. He held a job fair at the high school and ADP was there. They told him if he ever needed a job to call them. His wife died right after he retired. He was home for a while but then went to ADP. He was going to go for two years and he stayed for 24. And everybody loved him because he brought their checks!”35

Upon celebrating their 20th anniversary, Mary said, “We went on a cruise to the Caribbean. We’ve been on 57 cruises, the best way to travel. We’ve been to Tahiti and Iceland. You name it. It’s easy. They make your bed. They feed you, too, and they take you where you’re going. We’re going on another one for George’s birthday in November. He’ll be 97.”36

It’s not as though they were wealthy. “We were both teachers. In between, after my first husband died, I did some real estate work. I’m a good shopper. We’ve had a great life.”

Both Yankowskis had children from their first marriages. George had five daughters (Linda, Judi, Debi, Marcia, Lisa) and one son, George Jr. Mary had two daughters (Linda and Wendy) and two sons (William and Glenn). Between them, they also had 17 grandchildren and 17 great-grandchildren.

Over time, as major-league baseball salaries escalated dramatically, the major-league pension fund amassed billions of dollars. But many former players — like George Yankowski — lacked enough major-league service time to qualify for a pension. Author Douglas Gladstone’s 2010 book, A Bitter Cup of Coffee: How MLB & The Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve, brought their story to wider notice. In April 2011, the union and baseball announced an award to these overlooked men of up to $10,000 a year (based on length of service). However, they did not get health coverage, and the payments expired upon the player’s death, without anything going to a spouse or other designee. Yankowski said he’d use the money to cover needed dental work.37

Mary said, “George has a bone to pick with Major League Baseball. It’s a shame.”

Listening to the interview with Anne Keene, it was refreshing to hear the 95-year-old Yankowski recount his baseball memories with youthful enthusiasm and awe. He recalled one other Hall of Famer he’d played against in Cooperstown, New York: Stan Musial, star of the St. Louis Cardinals. “I think they were the champions. I was there calling pitches against Stan Musial! I had a lot of thrills like that. Playing against those guys. I think I was almost more of a fan than I was a ballplayer.38

“We talked about baseball. Dreamed about baseball. Baseball was it. I was kind of lucky. Can you imagine, me playing in the major leagues? For a little bit, I don’t care.”39

“I was pleased that I was able to wear a major-league uniform for a couple of teams — but I am very proud of having been in the war and having earned the Combat Infantry Badge and the Bronze Star. Baseball was great, but winning a war dwarfed that.”40

On February 25, 2020, George Yankowski passed away peacefully at The Villages in Florida with his wife Mary by his side.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Anne R. Keene for sharing the recording of her 2018 interview with George Yankowski. Thanks to Mary Yankowski for assistance with, and contributions to, the September 2019 author interview.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the Yankowski player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Author interview with George Yankowski on October 1, 2019.

2 Anne R. Keene interview with George Yankowski, July 8, 2018.

3 Tom Fitzgerald, “Watertown Baseball Squad Lacks Veterans for Battery,” Boston Globe, April 6, 1939: 21. A subhead read “Coach Sullivan May Use George Yankowski As Successor to Lavrakas As Catcher.” Lavrakas went on to become an admiral in the United States Navy.

4 Fitzgerald.

5 Fitzgerald.

6 Herbert Ralby, Schoolboy Sidelights,” Boston Globe, May 2, 1939: 21.

7 Ernest E. Dalton, “Schoolboy Sidelights,” Boston Globe, May 15, 1939: 9.

8 Ernest Dalton, “Watertown High Again Has Ace Battery of Calden and Yankowski,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1940: 24.

9 Frank Santarpio, “Catching Up with George Yankowski,” Watertown TAB and Press, June 26, 2009: 11.

10 See, for instance, “Huskies Beat Harvard, 5-2,” Boston Globe, April 23, 1942: 21.

11 Bartholomew. There was a Class-B Northern League in professional baseball in 1942, but it was not located in New England. He had been signed to the A’s by the end of the summer in 1942.

12 Gerry Moore, “A’s Notch Third Win Over Wagner,” Boston Globe, August 5, 1942: 21.

13 Author interview with George Yankowski on September 21, 2019.

14 Fred Barry, “Leaving N.U. Not Easy Decision for Yankowski,” Boston Globe, August 7, 1942: 34.

15 “Bob Dunbar’s Comment,” Boston Herald, August 20, 1942: 24. Fred Woodcock wrote a letter to the editor noting that at least one other catcher, Fred Tenney of Brown University, had made a similar jump.

16 Anne R. Keene interview.

17 Keene. He remembered being behind the plate when Ted Williams came up to bat. Bill McGowan was the plate umpire. “[Bob Savage] threw a ball belt high in the middle of the plate. The umpire said, ‘Ball one.’ I turned around. I spun around. A 19-year-old kid questioned a major-league umpire. And I said, “Jesus Christ!” The umpire went out of his head, yelling at me, but he didn’t throw me out of the game. He kept raving and ranting what a terrible thing I did to spin around and question him. Williams finally said, ‘For cripe’s sake, leave the kid alone.’ The pitcher throws another ball, the exact same place. The middle of the plate. Belt-high. And the umpire got about two inches from my ear and says, ‘Ball two. How do you like that?’”

18 “Jo-Jo White Signs,” Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), February 21, 1943: 48.

19 Ralph Wheeler, “Devens Nine Flails Coast Guard, 11-6,” Boston Herald, June 6, 1943: 78.

20 Fred Barry, “Babe Ruth, Ted Williams Cheered at Field Day,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1943: 14.

21 Anne R. Keene interview.

22 Keene

23 Keene

24 Sgt. John Bartholomew, “A’s Catching Ace Dons Mask, Leads Army Baseball Invasion,” The State (Columbia, South Carolina), May 7, 1944: 24.

25 http://87thinfantrydivision.com/historical-overview

26 Anne R. Keene interview.

27 https://history.army.mil/html/reference/bulge/index.html

28 Author interview, 2019.

29 Interview

30 Ernest Dalton, “New Watertown Coach No Baseball Rookie,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1951: 15.

31 Aida Press, “Watertown’s Work-Study Curbs Dropouts,” Boston Traveler, February 2, 1966: 1.

32 Aida

33 Author interview with Dick Berardino on September 28, 2019.

34 “Catching Up with George Yankowski.”

35 “Catching Up…”

36 Author interview with Mary Yankowski on September 19, 2019.

37 See Nick Cafardo, “Baseball,” Boston Globe, November 25, 2012: C14.

38 Anne R. Keene interview.

39 Keene

40 Author interview, 2019.

Full Name

George Edward Yankowski

Born

November 19, 1922 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

Died

February 25, 2020 at The Villages, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.