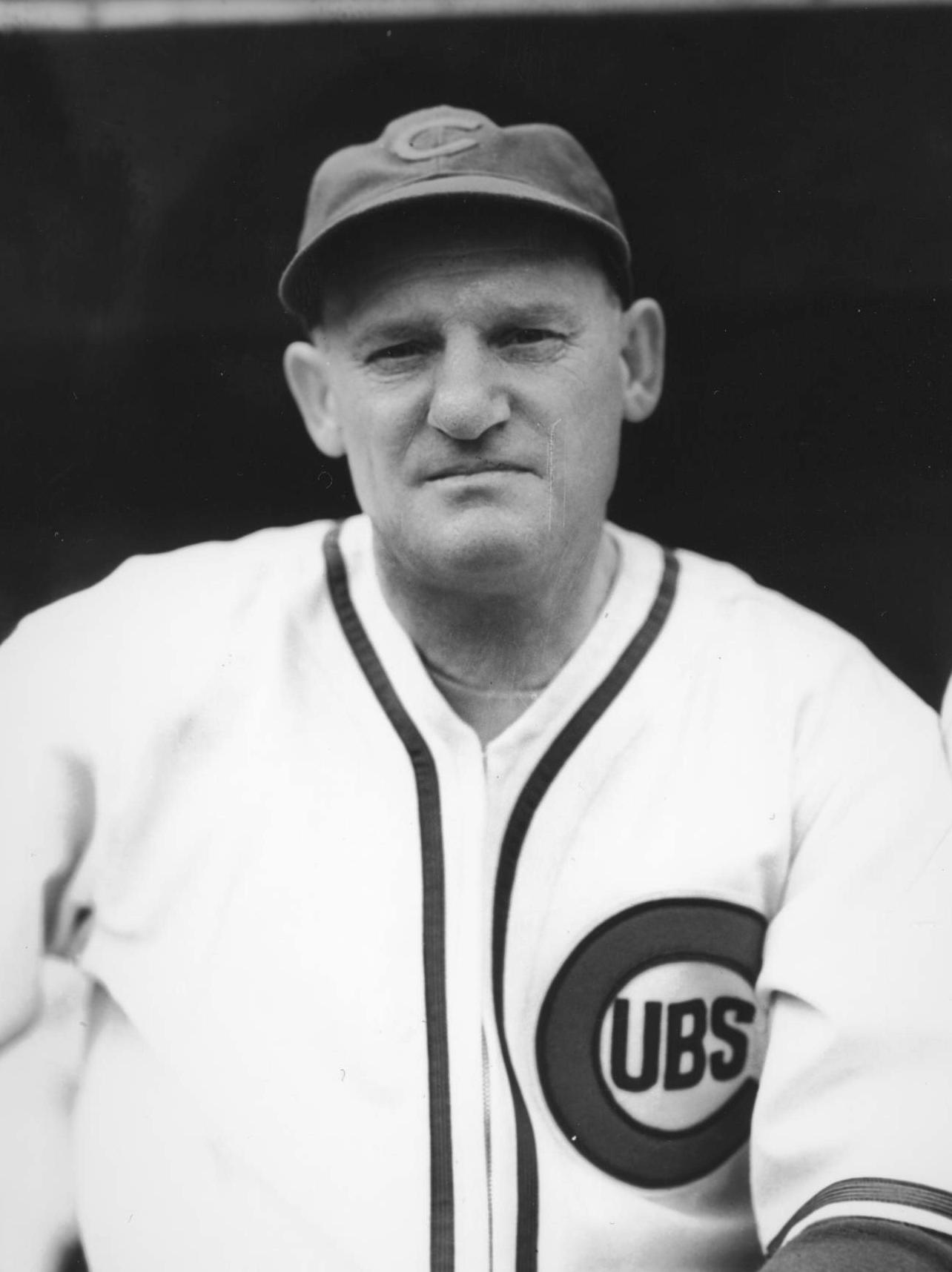

Hack Miller

In many ways, Lawrence “Hack” Miller was baseball’s version of the circus performer his father “Sebastian the Strong Man” had once been. Hack Miller entertained teammates by using his bare hand to pound tenpenny nails through two-inch planks of wood and taking the same-size nails and bending them with his fingers. It has been written that he pulled up “fair-sized trees by the roots” during spring training. He once was photographed holding a baseball bat above his head like a barbell, with a teammate hanging from each end. He bragged that one winter he lifted a car to free a woman who had been trapped beneath its wheels. And though he normally swung a 47-ounce bat, on occasion in the minor leagues he wielded a 65-ounce club that was two pounds heavier than those used by modern major leaguers of the 21st century.

In many ways, Lawrence “Hack” Miller was baseball’s version of the circus performer his father “Sebastian the Strong Man” had once been. Hack Miller entertained teammates by using his bare hand to pound tenpenny nails through two-inch planks of wood and taking the same-size nails and bending them with his fingers. It has been written that he pulled up “fair-sized trees by the roots” during spring training. He once was photographed holding a baseball bat above his head like a barbell, with a teammate hanging from each end. He bragged that one winter he lifted a car to free a woman who had been trapped beneath its wheels. And though he normally swung a 47-ounce bat, on occasion in the minor leagues he wielded a 65-ounce club that was two pounds heavier than those used by modern major leaguers of the 21st century.

Miller was short and squat at 5-foot-9, with a massive chest, broad shoulders, powerful arms and a listed playing weight between 195 and 208 pounds, although for much of his career he was overweight and slow.

But Hack Miller was more than a circus freak or a stuntman. He could hit, as evidenced by batting averages of .352 and .301 with 32 home runs in his two seasons as a regular with the Chicago Cubs in 1922-23. Sadly, Miller never became the star that he might have been had he been able to control his weight and utilize his amazing strength on the field and not just as a sideshow.

His career with the Red Sox was similarly tantalizing but brief. Called up in the final weeks of the 1918 pennant race, Miller made just one appearance in the Fall Classic, which, ironically, was against the Cubs, the team he later would spend three and one-half seasons with. That one at-bat came in the ninth inning of Game Five of the Series, with the Red Sox trailing the Cubs 3-0 at Fenway Park. Facing lefthander Hippo Vaughn, Miller hammered the ball into deep left field toward the farthest reaches of Duffy’s Cliff, so named for the great Red Sox outfielder Duffy Lewis, who was a master at fielding flies hit onto the steep incline in front of the left-field fence. The ball seemed headed for an extra-base hit that might spark a last-gasp Red Sox rally.

But as the crowd roared in anticipation, Cubs outfielder Les Mann raced up the incline, turned to gauge the arc of the ball, and then, even as he lost his footing and fell to a sitting position, somehow managed to reach up and make the catch in the webbing of his glove. As Burt Whitman wrote in the next day’s Boston Herald and Journal, “It was the most unusual [catch] made in that hilly stretch of territory which surely has seen some queer catches.”

That one moment was symbolic of Miller’s major league career: brief, dramatic, colorful, memorable, but just short of the stardom that many thought was his destiny.

Miller joined the Red Sox from Oakland of the Pacific Coast League on August 7, 1918, and Boston manager Ed Barrow said in the August 10 Herald and Journal that the young outfielder reminded him of the great Hans Wagner. But after the Series ended, Miller never again appeared in a Boston uniform. He terrorized PCL pitchers for the next three seasons, then turned in those two tantalizing seasons for the Cubs that put him on the verge of becoming one of the game’s premier power hitters. But following part-time duty in 1924 and the first month of 1925, a losing battle with weight problems drove Miller back to the minor leagues, where he continued to thrill fans in the Pacific Coast League, Texas League, and Three-Eye League with his hitting prowess and feats of strengths.

Despite his relatively short stay in the big leagues, Miller did leave his mark. He was widely considered the strongest man in baseball during his playing days, and if the many tales about him are true, then he might have been the most powerful man ever to play the game before steroids were introduced.

Both F.C. Lane, the widely respected writer for Baseball Magazine, and Cubs first baseman Charley Grimm wrote of witnessing Miller hammering nails through boards with his hand covered only with his baseball cap,. Historian Art Ahrens wrote in The National Pastime that as an 18-year-old apprentice steamfitter, Miller would hoist 250-pound radiators onto his shoulders and carry them up several flights of tenement stairs.

But there were many baseball men around the National League who looked at Miller’s powerful frame and dismissed him as “muscle-bound,” with his strength actually handicapping him as a player.

Grover Cleveland Alexander, the great pitcher for the Phillies, Cubs, and Cardinals, seemed to endorse this view of Miller when he was quoted in Lane’s 1925 book Batting:

“Even slugging at its worst is something of a science. It is surely not a matter of strength and weight. If it were, Hack Miller would be the greatest slugger in either league for he is by all odds the strongest man on the major circuits. But Rogers Hornsby can hit the ball harder than Hack. Miller is short, thickset, ponderous. Hornsby is tall, loose-jointed, of slender build. Hack could take him in his two hands and double him over his knees. In strength, there is simply no comparison. Besides, Hack probably outweighs Hornsby by 40 pounds. Still, Hornsby is the harder hitter of the two.”

Miller also rivaled Babe Ruth in using the heaviest bat in baseball history. Ruth’s 48-ounce bat is regarded by many as the heftiest in the major leagues, and Lane wrote in Baseball Magazine in 1925 that Ruth once used a 54-ounce club. While Miller’s 47-ounce bat was not quite as weighty as Ruth’s normal club, the 65-ounce one Hack claimed to use in the minors (he said he liked it because it didn’t sting his fingers when he hit with it) was off the scales compared with that of other baseball strongmen.

Despite his many feats of strength, Miller was a good-natured man who also entertained his teammates with his musical ability, playing a guitar that Grimm remembered as “held together with bicycle tape” in the Cubs’ string band. Sportswriters described Hack as having “a killing smile” and an easy-going disposition that allowed him to laugh off hecklers in the bleachers or pranks played on him by his teammates. On one occasion, while playing for Danville, Illinois, of the Three-I League late in his career, Miller found a snake in the outfield grass at Bloomington, Indiana. He took great delight in using the serpent to joke with the fans in the left-field bleachers, acting as if he were about to toss what Robert Poisall of the Danville Commercial News described as a “rattler” into their midst.

Miller came about his strength and muscular build naturally. He was born New Year’s Day in 1894 in New York City, but the next year, his father, Sebastian (a German immigrant whose real name was Mueller, according to the February 7, 1923, Los Angeles Times), moved the family to Chicago, where he operated a saloon. Miller later told Baseball Magazine that the establishment was a hangout for wrestlers and other toughs who liked to show off their strength with feats such as lifting 400 pounds using only one finger. The elder Miller, known as “Sebastian the Strong Man,” was himself a wrestler who could break cobblestones with his bare hands, according to Baseball Magazine. The Los Angeles Times reported that among Sebastian the Strong Man’s other stunts was taking a horse’s tail in each hand and holding the animals back while trainers tried to lead them in opposite directions.

Hack Miller inherited his father’s strength and stocky build, but the younger Miller said he was neither as large nor as strong as his father. However, as young Hack matured, he began to resemble a famous wrestler of his day, the Russian strong man George Hackenschmidt. This generally is considered the source of Miller’s nickname “Hack,” although Edwin F. O’Malley of the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1918 that Miller earned his nickname in 1917 because his fat did a ballet dance as he “scudded after a fly ball.”

As a boy, Hack played in neighborhood football games, but he told Baseball Magazine that “there was a rough crowd, nothing like rules and I got badly hurt.” His parents forbade him to play again, so he turned his attention to other athletic endeavors.

Despite his size and strength, Miller was surprisingly agile and athletic. He worked three years at the Chicago department store Marshall Field, which entered teams in local athletic competitions. Miller told Baseball Magazine that he collected a boxful of medals in these meets, displaying his versatility by pole-vaulting more than nine feet, broad-jumping more than 17 feet, and running the 100-yard dash in less than 11 seconds.

But it was in baseball that Miller would gain national acclaim. After playing semipro ball in the Chicago area, he began his professional baseball career at the age of 20 with Wausau of the Wisconsin-Illinois League, where he batted an impressive .333 with nine homers and nine stolen bases in 72 games in 1914.

Miller moved up to the Class C Northern League the following season, and he showed the speed he later boasted of by hitting 12 triples and stealing 14 bases to go with a .306 batting average for St. Boniface, prompting Brooklyn of the National League to draft him in August.

In 1916, Brooklyn assigned Miller to Winnipeg of the Northern League, and he not only won the batting title with a .335 average but also set what was reported as a world record for the longest drive with a fungo bat. Competing in a contest on June 19, Miller hit a fungo 438½ feet, beating the old record held by major league pitcher Big Ed Walsh by a full 19 feet, according to Minor League Encyclopedia. Hack also experienced night baseball more than 20 years before it was introduced in the major leagues, as the long summer days in Winnipeg allowed the team to play games until 10 or 11 p.m.

Miller’s strong season earned him his first shot at the major leagues, as Brooklyn called him up in August 1916. He appeared in three games, hitting a triple with an RBI in three at-bats, but he was sold to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League on September 26, before the Robins played in the World Series against the Red Sox. It wouldn’t be long before Miller got another shot at the Fall Classic.

Playing in Class AA, the minor leagues’ highest designation at the time, Miller batted .296 with 12 triples for the Oaks in 1917. Despite his stats, Miller carried too much excess weight to suit Oakland manager Del Howard, who ordered him to shed some pounds over the winter.

Miller did just that, reporting to camp in the spring of 1918 more than 20 pounds lighter. The benefits were immediate, as Hack batted .316 through 102 games and was leading the PCL in hits with 131, prompting O’Malley of the Los Angeles Times to marvel that Hack could run the 100-yard dash in under 11 seconds and “base it like a Ty Cobb.”

The glowing reports on Miller caught the attention of Red Sox manager Ed Barrow, who signed the young outfielder on August 3 to provide Boston with a much-needed right-handed bat to play the outfield on days when Babe Ruth was called upon to pitch. Although Miller batted only 29 times in 12 games as a pinch hitter and occasional starter in left field against left-handed pitchers in the stretch drive of the pennant race, he hit a respectable .276 with two doubles and four RBIs. Still, by the end of the regular season, Miller had lost out to another late-season addition, 35-year-old George Whiteman, as the back-up leftfielder, and Hack made only the one pinch-hit appearance in the World Series.

That would mark the end of Miller’s career with the Red Sox, as the following spring he was sold back to Oakland, where over the next three seasons he posted batting averages of .346, .347, and .347. A broken leg in 1919 limited him to 54 games, but in 1920 Miller led the PCL with 280 hits and in 1921 his .347 average was second only to former Red Sox Duffy Lewis’ .403 in 300 fewer plate appearances (league records show Miller as the batting champion, but official records show Lewis as the winner, according to SABR’s Bob Hoie).

Still struggling to keep his weight under control, Miller played winter ball that off-season, and in January 1922 he was signed by the Cubs to fill a void in left field. Hack’s reputation as a batter and a strong man preceded him to the Cubs’ training camp on Catalina Island, off the Southern California coast, so he was under a lot of scrutiny from the time he stepped off the boat following the two-hour ride from Los Angeles. A writer for the Chicago Daily Tribune took one look at Miller and reported that he was “carrying enough beef to make a couple of ballplayers. He looked much like Ping Bodie when the latter was not in trim. Hack has a pair of shoulders that appear to measure something like a city block across.”

Although Miller got off to a slow start that season, he began hitting when the weather warmed up, and he finished the season third in the league in batting with a .352 average as well as 12 homers and 78 runs batted in. Hack’s most memorable moment came on August 25 when he hit a pair of three-run homers to help the Cubs beat the Phillies 26-23 in the highest-scoring game in major league history.

When Miller followed up with a .301 average, 20 homers, and 88 RBIs in 1923, he appeared to some to be on his way to stardom. More savvy baseball experts had their doubts. Hugh Fullerton, the great baseball writer for the Chicago Daily Tribune, wrote of him on October 1, 1923:

“Miller is a sturdy and always trying type of ball player, a fence buster, and one of those fellows who will kill the weak pitching. He can take toe holds and crack ’em high up and far away, and then prove a sucker to an ordinary pitcher with control. He is slow on the bases, but covers an amazing amount of ground in the outfield for one so slow. He is working all the time and fairly good in aiding his center fielder. In retrieving balls hit between left and center he is all right until it comes to throwing.”

Decades later, in the October 4, 1982, issue of the New York Times, Bill Veeck Jr. wrote that his father, Bill Veeck Sr., the general manager of the Cubs in the 1920s, was so enamored with Miller that in 1924 he added new bleachers to shorten the left-field fence at Cubs Park by 50 feet, hoping to boost Hack’s home run total. According to Veeck Jr., opposing pitchers responded by pitching Miller low and away, causing him to hit harmless popups, and after Giants first baseman Bill Terry hit two homers into the shortened bleachers his first two at-bats, the Cubs tore down the bleachers before the next game.

However, Veeck’s memory was faulty. It was Hack’s weight and manager Bill Killefer’s preference for speed, not the Chicago ballpark, which led to Miller’s demise with the Cubs. The only changes to Cubs Park that the Chicago Daily Tribune reported in 1924 were the removal of advertisements from the outfield fences and a rebuilt scoreboard that could display the American League scores in addition to those of the National League. It was in 1926 that Cubs Park was renamed Wrigley Field and the bleachers in left field removed as part of a renovation that almost doubled the stadium’s seating capacity.

Hack was gone by then, but he did play with the Cubs throughout 1924. Although losing his starting job in left field to Dallas Grigsby that season, Miller was a valuable part-time player and pinch hitter, batting .336 in 53 games. According to Arthur Daley of the New York Times, Miller also passed on his nickname to a future Cubs great who, when joining the team as a rookie in spring training 1924, , reminded his teammates of “a sawed-off Hack Miller,” leading him to become known as “Hack” Wilson.

Miller played only sparingly early in the 1925 season, and on May 21, he made his last big-league appearance, hitting a pinch-hit triple in a 5-4 loss at Brooklyn. Three days later, he was given his release and returned to Oakland, where he had made his winter home.

He clearly was struggling to keep down his weight, and although Hack batted .321 after joining Oakland in 1925, the following spring he reported to camp “so fat he hasn’t been able to perform,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. Midway through the season, the Oaks sold Miller to Houston, where he rounded into shape well enough to bat .367 for the Buffs.

In 1927, Hack split his time between Houston and Beaumont of the Texas League, batting .340, and Danville of the Three-I League, where he batted .311 and led his team to the pennant.

Danville marked the end of Miller’s playing career, although some record books incorrectly credit him with playing for Houston in 1929. The mistaken identity was understandable considering that in the same circuit there was another Hack Miller, who in 1926 had led the league in home runs to power Dallas to the pennant and the Dixie Series championship over the Southern Association champions. To add to the confusion, both Hack Millers were stocky, muscular power hitters.

In 1928, Dallas sold its Hack Miller to Minneapolis of the American Association, where he enjoyed a solid season before weight problems led to his being shipped back to the Texas League in 1929. Both the Houston Post and Houston Chronicle heralded the signing of the former Dallas slugger who, as the Chronicle warned, “is not to be confused with the Hack Miller who played with Houston three years ago.”

By that time, Lawrence “Hack” Miller, once hailed as the strongest man in baseball, had returned to his home in Oakland, where his strength gained him employment as a dock worker. Miller eventually became a crew boss on the waterfront before retiring in 1959. He remained in Oakland until his death at 77 on September 17, 1971. He was buried in Oakland’s St. Mary Cemetery.

Miller’s legacy is that of a baseball strong man who performed amazing feats of strength in an era before weight training and steroid use. But one can only wonder how good Miller might have been had he had the discipline and the training to better utilize that strength and control his weight. He never was able to do that, and as a result Hack Miller’s feats on the field never matched those off it.

Sources

Ahrens, Art. “Cub Strongman,” The National Pastime, Vol. 10, 1990.

___________. “Would You Believe, 49 Runs in One Game,” Baseball Digest, December 1974.

Grimm, Charlie, with Ed Prell. Grimm’s Baseball Tales: Jolly Cholly’s Story (Notre Dame, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1983). Originally published under the title Jolly Cholly’s Story: Baseball, I Love You! (Henry Regnery Company, 1968).

Hoie, Bob. “Determining Batting Champions,” SABR Minor League Newsletter, June 2002.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, editors. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1993).

Lane, F.C. Batting: One Thousand Expert Opinions on Every Conceivable Angle of Batting Science (New York City: Baseball Magazine Co., 1925). 68.

_________. “The Importance of Physical Strength in Baseball,” Baseball Magazine, September 1925.

Richter, Francis C., editor. Reach Official Base Ball Guide (Philadelphia: A.S. Reach, 1916).

Spalding, John. “Hack Miller,” in Pacific Coast League Stars: One hundred of the best, 1903 to 1957 (Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1994).

Waggoner, Glenn, Kathleen Moloney, Hugh Howard. Spitters, Beanballs, and the Incredible Shrinking Strike Zone (Chicago: Triumph Books, revised edition, 2000).

Who’s Who in Baseball (New York: Baseball Magazine Company, issues 1920-28).

Newspapers and periodicals

Boston Herald and Journal

Chicago Daily Tribune

Dallas Morning News

Danville (Illinois) Commercial-News

Houston Chronicle

Houston Press

Los Angeles Times

Minneapolis Tribune

New York Times

Oakland Tribune

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Full Name

Laurence H. Miller

Born

January 1, 1894 at New York, NY (US)

Died

September 16, 1971 at Oakland, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.