Harry Bay

Once clocked on a stopwatch from plate to first in 3.5 seconds, Harry Bay was considered by many contemporary baseball authorities to be the fastest man in the American League. A photographer experimenting with a motion picture camera filmed “Deerfoot” in full stride and newspaper reports commonly referred to the speedster as “a ten-second man in the 100 yard dash.” Bay used his blazing foot speed to forge a reputation marked by splendid base running, spectacular catches, and acrobatic dives. At the plate, he mastered the chop swing to further exploit his natural talents. A left hander, Bay played both sides of the game – offense and defense – with reckless abandon. He was especially adept at sliding headlong into first base on particularly close plays. One account mused that Bay was so slender – 5’8″ and 138 pounds

Once clocked on a stopwatch from plate to first in 3.5 seconds, Harry Bay was considered by many contemporary baseball authorities to be the fastest man in the American League. A photographer experimenting with a motion picture camera filmed “Deerfoot” in full stride and newspaper reports commonly referred to the speedster as “a ten-second man in the 100 yard dash.” Bay used his blazing foot speed to forge a reputation marked by splendid base running, spectacular catches, and acrobatic dives. At the plate, he mastered the chop swing to further exploit his natural talents. A left hander, Bay played both sides of the game – offense and defense – with reckless abandon. He was especially adept at sliding headlong into first base on particularly close plays. One account mused that Bay was so slender – 5’8″ and 138 pounds

– that he did not even cast a shadow on sunny days. His thin build earned Bay a second nickname, “Sliver,” and surely qualified him as one of the slightest men in professional baseball.

Harry Elbert Bay was born on January 17, 1878, in Pontiac, Illinois, to George and Martha (Springer) Bay. When he was five, Harry’s family relocated to Peoria where he learned how to play sandlot baseball. Later, he became “an all-around athlete” at Peoria High School. After graduation Bay barnstormed the Midwest on a team which included a young pitching prospect from Rock Island – future Hall of Famer Joe McGinnity. Bay’s stellar fielding and base running attracted the attention of local minor league clubs, and he signed his first professional contract with independent Lincoln (Illinois) in 1898.

Bay rose quickly through the ranks of the minor circuits. Playing for Rock Island of the Western Association and Troy of the New York State League in 1899, he moved on a year later to play for Detroit in the American League – one year before that circuit declared major league status – and for Marion (Indiana) of the Inter-State League. His break came in 1901 with a great performance for the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western Association, where he hit .303, stole 24 bases, and fielded .949. By midsummer, the Cincinnati Reds opened a roster spot for the fleet-footed outfield prospect.

Bay appeared in his first major league contest on July 23, 1901 against Pittsburgh. He normally batted leadoff and played centerfield, but saw limited action in 41 games and hit a disappointing .210. Cincinnati sportswriters labeled the rookie “a thirty center,” a disparaging reference to ordinary skills.

Bay received his release from the Reds in May 1902 and promptly signed with the Cleveland Bronchos, who were in a desperate position because of injuries sustained by left fielder Jack McCarthy and right fielder Elmer Flick. Bay auspiciously starred in his first game when he collected a pair of singles and a double, stole one base, and initiated a double play from the outfield. The following day he hit safely in three appearances. Although the ailing outfielders returned to the Blues lineup, Bay had earned a spot and replaced Ollie Pickering in center field. Appearing in 108 games, he batted a respectable .290 and swiped 22 bases. At one point, Deerfoot produced a 26-game hitting streak. Moreover, he led all American League centerfielders with a .973 fielding percentage. In his first season with the Blues, the likable Bay also made an impression upon the Washington, DC police, who fined the Cleveland player $25 for placing his signature on the Washington Monument.

1903 promised to be Bay’s breakout season. He remained consistent in the lead off role with a .292 average, and pilfered 45 “pillows” to lead the American League. He also placed high in other categories as well: 579 at-bats (2nd), 169 hits (4th), 94 runs scored (5th), 201 times on base (9th), 25 sacrifice hits (4th), and 12 triples (10th). Bay’s personal life also began to take off with his marriage to Lelia Ballinger. In the off-season Harry and Lelia joined the vaudeville act of Guy Kibbee, who would later become well known as a character actor in Warner Brothers western and gangster films. A natural entertainer, Harry was widely recognized as an accomplished cornet player.

By his own admission, Bay suffered from the effects of running on hard base paths. When he suffered an injury to one of his “underpinnings” (legs) in 1904, Harry slumped to a .241 average. The nimble one still managed to steal 38 bases and dazzle crowds with his athleticism in the field. On July 19 Bay registered 12 outfield putouts in a twelve-inning contest against Boston to set a major league record. Less than two weeks later against Washington, he tracked down a towering fly ball launched to the deepest part of the park. Turning his back to the plate, Harry made a spectacular over-the-shoulder grab barehanded.

Bay returned to form in 1905, posting some of the most impressive numbers of his career. He batted a personal best .301 and nabbed 36 bases. Harry also banged out 166 hits (fifth in the American League), and twice tallied five hits in a single game. On the same day that he became the first American Leaguer to reach the coveted mark of 100 hits (July 27), he injured his left shoulder while diving into a bag. Several days later, he aggravated his right knee while slipping and sliding for fly balls on a muddy field. The lame Deerfoot never returned to top form; indeed, the damaged knee plagued Bay for the remainder of his baseball life.

Sidelined for much of the last year of his career in Cleveland, on June 13, 1907, a frustrated Bay asked to be traded to the Boston Americans. “Maybe there can be torture more acute to an ambitious ball player than sitting stock still while his team mates are out there hustling for victory,” revealed Bay, “but I’ve yet to learn what it can be.” The trade never materialized, and when adoring fans sent Bay a loving cup in appreciation of his efforts in Cleveland flannels, it signaled the end of his career. He literally limped through his last major league game on May 3, 1908. His eight-year career numbers (.273 batting and .968 fielding averages) were worthy. More significant were Bay’s 169 stolen bases, largely accomplished over four healthy seasons.

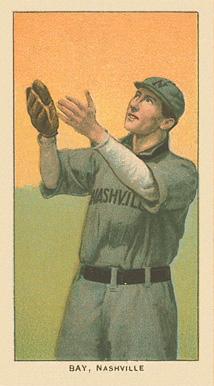

When Cleveland skipper Nap Lajoie shipped Bay to Nashville in the spring of 1908, the recuperating outfielder was reunited with his former Blues teammate and current manager of the Vols, Bill Bernhard. “Strawberry Bill” immediately inserted the gimpy Bay into the Volunteer lineup, and the veteran big leaguer responded with three bases on balls, three stolen bases, and three runs scored to lead the way in a 6-2 victory over archrival Memphis. Bay played left field and appeared in 123 games for the Vols while batting a crisp .283. But he was best remembered by local fans for laying down a perfect bunt single to load the bases and keep a rally alive in the key inning of the championship game, which resulted in a 1-0 victory and gave Nashville the 1908 Southern League crown.

Bay remained a crowd favorite in Nashville for three more seasons, as he posted consistent offensive and defensive numbers despite being hampered by the bum knee. Once Bernhard departed for Memphis, Bay left Nashville and decided to try his own hand as a minor league player-manager. He worked mostly in the Three-I League: Bloomington, Illinois (1912); Madison, Wisconsin (1913-1914); Rock Island, Illinois (1916); and Alton, Illinois (1917) – and also Mason City, Iowa of the Central Association (1915).

When Bay finally retired from professional baseball he returned to his hometown to work as a state automobile license examiner. He is best remembered locally, however, as the secretary and later switchboard operator for the Peoria Fire Department. Hearing about the latter post, Connie Mack sent a congratulatory note: “I bet you’re the first one at every fire,” noted Mack whimsically. “Such speed as you had will never be forgotten.”

Bay’s musical career held equal prominence in his life. “His fame as a trumpet virtuoso almost equaled that of his big league ball playing,” claimed the Peoria Journal. For years, Bay was a featured soloist with the Peoria Municipal Band and performed regularly with the Shriners’ Marching Band and the American Legion band. He also formed his own group and entertained at numerous local dances.

During the frosty winter of 1951-1952, Bay slipped on an icy sidewalk and fractured several ribs. He was in considerable discomfort and bedridden for five weeks. Then, on March 20, 1952, at age 74, Harry Elbert Bay died from a coronary occlusion. He was buried alongside his wife, who preceded him in death, at Parkview Cemetery, Peoria.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Peoria Journal, 21 March 1952

Peoria Daily Record, 7 Feb. 1939.

Harry Bay, Player Career Index, The Sporting News Archive, St. Louis, MO.

Harry Elbert Bay file, A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, N.Y.

Scott Longert, Addie Joss; King of the Pitchers (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1998): 50

Russell Schneider, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996): 254

The Sporting News, 2 April 1952

Reach Guide, 1910, 274; 1911, 284; 1912, 240

Marshall Wright, The Southern Association, 113, 140, 145

Full Name

Harry Elbert Bay

Born

January 17, 1878 at Pontiac, IL (USA)

Died

March 20, 1952 at Peoria, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.