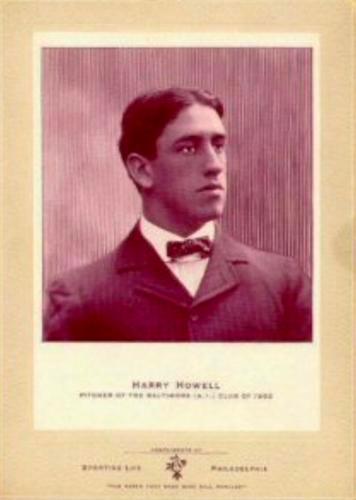

Harry Howell

A stocky 5’8″ right-hander who threw one of the wettest spitballs in baseball history, Harry Howell was the St. Louis Browns’ best pitcher during the Deadball Era, establishing a franchise record for career ERA (2.06) that has never been equaled. Howell learned his singular pitch from spitballing legend Jack Chesbro in 1903, and subsequently relied on it almost exclusively. Indeed, Howell’s method of loading-up the ball disgusted those who thought it uncouth and unsanitary. Eddie Collins once said, “Howell used so much slippery elm we could see the foam on his lips and on hot days some of the boys thought he was about to go mad.” Some sources claim the error rates of Browns infielders spiked whenever Howell was pitching, as fielders unsuccessfully attempted to grip the saliva-soaked sphere. Known as “Handsome Harry,” Howell was also a fan favorite during his seven years with the Browns, especially among women, a situation which brought about the demise of Howell’s first marriage.

A stocky 5’8″ right-hander who threw one of the wettest spitballs in baseball history, Harry Howell was the St. Louis Browns’ best pitcher during the Deadball Era, establishing a franchise record for career ERA (2.06) that has never been equaled. Howell learned his singular pitch from spitballing legend Jack Chesbro in 1903, and subsequently relied on it almost exclusively. Indeed, Howell’s method of loading-up the ball disgusted those who thought it uncouth and unsanitary. Eddie Collins once said, “Howell used so much slippery elm we could see the foam on his lips and on hot days some of the boys thought he was about to go mad.” Some sources claim the error rates of Browns infielders spiked whenever Howell was pitching, as fielders unsuccessfully attempted to grip the saliva-soaked sphere. Known as “Handsome Harry,” Howell was also a fan favorite during his seven years with the Browns, especially among women, a situation which brought about the demise of Howell’s first marriage.

Harry Taylor Howell was born somewhere in New Jersey on November 14, 1876, the fourth child of Edward and Helen Howell. Harry learned the baseball craft on the sandlots of Brooklyn, and was employed as a plumber when the Meriden Bulldogs of the Connecticut League signed him for the 1898 season. Unofficially, Howell ran up an 18-13 twirling record in addition to a .209 batting mark as an extra outfielder for the defending champion Bulldogs.

Sold to his hometown Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the National League, Howell debuted as a pitcher in the major leagues by defeating Philadelphia twice within a six-day period in mid-October 1898. The convenience of playing for his hometown team was short-lived however, and over the next five seasons Howell bounced between Brooklyn and Baltimore, operating as a pawn in high stakes games played by baseball’s magnates. In 1899, Howell pitched for Baltimore of the National League, registering a 13-8 record. At the end of the season the Orioles were contracted, however, so Howell went back to Brooklyn, winning six and losing five in 1900 before jumping back to Baltimore when that city was awarded an American League franchise in 1901. Playing for John McGraw again, Howell displayed his versatility, hurling 294⅔ innings, and also appearing at first, second, shortstop and in all three outfield positions, batting .218 with two home runs and 26 RBI. He continued in the utility role with the 1902 Orioles, playing in 96 games, including 52 in the infield and 18 in the outfield, batting .268 in 347 at-bats, and leading the last-place, poorly supported, and soon-to-be-relocated Orioles in innings pitched.

When Ban Johnson moved the failed Baltimore franchise to New York after the 1902 campaign, Howell went along, and was credited with the first victory in New York Highlanders history on April 23. Up to that time, Howell had relied exclusively on a fastball and curve, and was never better than an average major league pitcher. But thanks to the instruction of teammate Jack Chesbro, Howell began to experiment with the spitter. The initial results were mixed, as Howell finished the year with a 9-6 record and mediocre 3.53 ERA.

Traded by manager Clark Griffith to the Browns on March 6, 1904–along with $8,000 cash–in exchange for pitcher Jack Powell, Howell began a productive five-year run in St. Louis for manager Jimmy McAleer. Now armed with a nasty spitball which he featured regularly, Howell averaged 308 innings a season from 1904 to 1908 and yielded earned runs at a rate of 2.02 per nine innings, a half run below the league average. In 1905 he led the American League in complete games with 35. Playing for the floundering Browns franchise, however, hurt Howell’s record, as he lost 13 more games than he won in a Browns uniform. Twice a 20-game loser with St. Louis, Howell’s best season with the Browns came in 1908, when he registered 18 wins against 18 losses with a 1.89 ERA. In contrast to his time with New York, Howell only rarely appeared at other positions for the Browns, posting his best average with the club in 1907, when he batted .237 with two home runs.

The spitter became both a source of Howell’s success and also a contributing factor in his failures. An enthusiastic proponent of the spitball, Howell, according to one report, “simply loves to throw the ‘spitter’ and tries his hardest to retire every batter on strikes. When pitching, Howell always has a mouth full of slippery elm and he simply covers the ball with saliva. When Howell is pitching, the infielders always complain about handling the ball.” The infielders’ difficulty may have contributed to his uneven record, as Howell typically gave up more unearned runs than the average Browns pitcher. In 1905, for example, when Howell went 15-22 despite a 1.98 ERA, he surrendered 38 unearned runs, 35 percent of his total runs allowed. The league average that year was 29 percent, a figure in line with the rest of the St. Louis pitching staff.

Occasionally a springtime holdout and always a tough salary negotiator, Howell was nonetheless very popular in St. Louis with his teammates, the sportswriters, and the fans, particularly those of the fairer sex. “Handsome Harry” became separated from his wife, Susie, in August of 1907 after she found a letter in Howell’s coat pocket from a Detroit woman that called him “the dearest and sweetest of men” and asked why he had not kept a promise to see her. Mrs. Howell also contended that a woman living near the St. Louis ballpark had received Harry’s attentions. The Howells could not reconcile and divorced on December 23, 1907, after six years of marriage.

Howell spent his winters in St. Louis, where he had an offseason job with the local water utility. In November of 1908, Howell made his debut appearance as a vaudevillian at the American Theater in St. Louis, “much to the delight of the gallery, which corresponds to the bleachers at the baseball park.” He had been hired to comment upon the moving pictures of the recently completed 1908 World Series games that were being projected upon the big screen. Howell, for years an amateur pianist, hoped to eventually appear on stage as a singer. Oddly, he credited singing lessons with improving his pitching game: “Stomach went bad and the result was that about the sixth inning in every game it would turn on me and I would weaken and be hit hard. I was told singing would strengthen the muscles of the stomach and diaphragm, and so I began to study for physical relief. As I kept up my studies my ailment disappeared, my stomach was restored. My teacher showed me the beauty of music of the higher class, and it has grown steadily. Formerly baseball was everything; now it is music and baseball.”

Due to injury, Howell’s career as a baseball player soon wound down. In the spring of 1909, Howell threw out his arm taking infield practice at third base. Something tore loose in his shoulder, putting him on the shelf for most of the 1909 season. After 12 months of failed rehabilitation, Howell had surgery on his ailing wing in March of 1910. The surgery was not successful and he was forced to retire from the mound. He spent the rest of the spring as new manager Jack O’Connor‘s pitching coach, then after one final, disastrous game in a mop-up role, spent the summer working as a scout for the Browns.

Howell’s association with the American League came to an unfortunate conclusion in October, 1910, when he was implicated in the scandal surrounding the Ty Cobb–Napoleon Lajoie batting race. On the final day of the season, O’Connor instructed Browns rookie third baseman Red Corriden to play deep on Lajoie, in order to allow the Cleveland second baseman to boost his batting average with bunt hits. After tripling in his first at bat, Lajoie dropped down eight bunts, seven of which were ruled as hits. When one of the bunts was ruled a sacrifice, Howell went up to the press box to try to convince the official scorer, Victor Parrish, to change his ruling. Parrish refused, but Howell remained around the press box for some time attempting to plead his case. At one point, a local bat boy brought an unsigned note promising a suit of clothes if Parrish would change his ruling. Reports conflicted as to whether or not Howell was the author of the note, but in either event once the affair was brought to light both O’Connor and Howell were fired by St. Louis owner Robert Hedges. Neither man ever worked again in the American or National leagues. When asked, Howell claimed he “acted merely as the emissary of friends and had no interest in the controversy.”

His major league career over, Howell played 89 games at second base for Louisville and St. Paul of the American Association in 1911, batting a solid .260. His arm was still wrecked by the 1909 injury however, and he made no pitching appearances in his final playing season. From 1912 to 1914, Howell worked as an umpire in the International and Texas leagues, before winning a spot as a Federal League umpire for the 1915 season. This appointment lasted only a few months, until late July, when Howell was released after an on-field brouhaha with St. Louis Federals’ manager Fielder Jones. After that Howell umpired in the Northwestern League for a time. Howell’s former manager, McAleer, called him “one of the best umpires that ever stood behind the bat.”

Following his baseball career Howell migrated Seattle, where by 1920 he was living in a downtown boarding house with his new wife, Marie, and working as a steamfitter in the shipyards. He later moved to Spokane, Washington, where he worked as a mining engineer, and later, as a bowling alley manager, hotel manager, plumber, and truck driver. Howell also served as a trusted advisor to Spokane team owner Bill Ulrich, and in 1941, Howell and Ulrich created the Star Baseball card game and published a book, Ulrich’s Baseball Manual: All Baseball Plays For the Young Ball Players and Baseball Fans of America, which Howell described as a “guide to show [young players] the right way to develop themselves.” Despite this activity, Howell and Marie struggled financially in their later years, and for a time lived rent-free at a Spokane hotel owned by Ulrich.

In May of 1956, Howell developed gangrene in his left foot. After an operation at St. Luke’s Hospital in Spokane, he died on May 22 from heart failure. He was six months shy of his 80th birthday and left no known descendants. Howell is buried next to Marie, in the non-endowed section of the Greenwood Memorial Terrace in Spokane.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

John Thorn and Pete Palmer. Total Baseball, 7th ed. Total Sports Publishing, 2001.

Baseball-Reference.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Reach Guide, 1912.

Sporting Life, multiple issues, but specifically:

Connecticut League boxscores, May through September, 1898

“Meriden’s Loss,” author unknown, Sept. 24, 1898, pg. 8

“The League Draft,” as submitted by N.E. Young, Oct. 8, 1898, pg. 4

“Connecticut League,” 1898 season statistics, Oct. 22, 1898, pg. 10

“The ‘Spit’ Ball,” by Cy Sanborn, Apr. 20, 1907, pg. 16

“Deadly ‘Spit’ Ball,” author unknown, May 18, 1907, pg. 20

“Harry Howell,” author unknown, June 20, 1908, pg. 5

The Sporting News, multiple issues, but specifically:

“Spit Ball And Its Elusive Shoots,” by Harry Howell, Oct. 29, 1904, pg. 2

“A Voice Out Of The Past,” letter from Harry Howell, May 1, 1941, pg. 9

Washington Post, multiple issues, but specifically:

“Jennie Calls Him Dearest,” author unknown, Dec. 24, 1907, pg. 8

“Mike Donlin Has Rival,” author unknown, Nov. 4, 1908, pg. 8

“Sings So He May Pitch,” author unknown, Dec. 20, 1908, pg. M4

“Howell’s Arm In Bad Shape,” author unknown, Apr. 8, 1909, pg. 8

“Brown Colts Win Again,” author unknown, Mar. 9, 1910, pg. 8

“Nationals Manifest Great Interest In Their Practice,” by J. Ed Grillo, Mar. 10, 1910, pg. 8

“Pitcher Howell Unable To Play,” author unknown, Mar. 15, 1910, pg. 8

“Sporting Facts And Fancies,” by Joe S. Jackson, June 17, 1910, pg. 8

“Official Scorer Says Howell Worked Hard To Help Lajoie Out,” author unknown, Oct. 14, 1910, pg. 8

“Howell Not Under Cloud,” author unknown, Feb. 5, 1911, pg. S3

“Many Jumpers In Front Ranks,” author unknown, Jan. 18, 1915, pg. 8

“Lajoie Makes Eight Safeties And Brings About Sensation,” author unknown, Feb. 11, 1917, pg. S2

Miscellaneous newspapers, but specifically:

“Federals Sign Up Three New Umpires,” author unknown, Christian Science Monitor, Dec. 16, 1914, pg. 22

“Fielder Jones Suspended,” author unknown, New York Times, July 7, 1915, pg. 12

“Federals Release Umpires,” author unknown, Christian Science Monitor, July 27, 1915, pg. 18

“Twenty One Years Of Base Ball,” by Eddie Collins, Los Angeles Times, Jan. 15, 1927, pg. 12

” ‘Handsome Harry,’ Former Major Leaguer, Dies,” author unknown, Spokesman-Review (Spokane, WA), May 24, 1956

Miscellaneous sources:

Clippings and information from Harry Howell’s player file at the Baseball Hall Of Fame (provided by Gabriel Schechter), including un-referenced and undated newspaper articles and obituaries, contract cards, and death certificate.

United States Federal Census information, 1880

The staff of the Greenwood Memorial Terrace, Spokane, WA

Kind assistance provided by SABR members Jim Price (Spokane historian; provided quote from Dwight Aden), Dave Eskenazi (provided a copy of Ulrich’s Baseball Manual), Steve Steinberg (provided Sporting News articles on Howell), and Bob Schaefer (provided research and made referrals regarding the rosters of the early Eckfords and Mutuals)

Full Name

Harry Taylor Howell

Born

November 14, 1876 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

May 22, 1956 at Spokane, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.