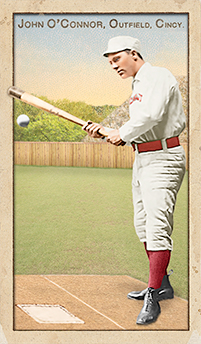

Jack O’Connor

Right-handed Jack O’Connor used his competitiveness and baseball intelligence, along with a penchant for playing multiple positions, to appear in the major leagues during 21 different seasons. His longevity includes him in the group of 29 players who have appeared in a game in four or more different decades. “Peach Pie” was his rookie handle, representing his roots, while “Rowdy Jack” represented his middle career. By the time he reached elder statesman status, the players referred to him as “King Jack.” He was a very competitive player who wasn’t afraid to fight for his side in any argument. His direct involvement in a very controversial moment in baseball history led to his being blackballed by Organized Baseball.

Right-handed Jack O’Connor used his competitiveness and baseball intelligence, along with a penchant for playing multiple positions, to appear in the major leagues during 21 different seasons. His longevity includes him in the group of 29 players who have appeared in a game in four or more different decades. “Peach Pie” was his rookie handle, representing his roots, while “Rowdy Jack” represented his middle career. By the time he reached elder statesman status, the players referred to him as “King Jack.” He was a very competitive player who wasn’t afraid to fight for his side in any argument. His direct involvement in a very controversial moment in baseball history led to his being blackballed by Organized Baseball.

John Joseph O’Connor was born on June 2, 1866,1 in St. Louis, Missouri, the oldest of six children of Patrick and Johanna O’Connor. His parents were first generation Irish immigrants; Patrick was an unskilled laborer and Johanna a housekeeper. By the 1900 Federal census Patrick had become a night watchman and owned the family home on North 12th Street, right in the heart of St. Louis’s Irish neighborhood. All six of the couple’s children — John, James, Michael, Nora, Mary, and Patrick — were still living at home.

O’Connor learned his baseball trade on the vacant lots and ball fields of the Kerry Patch neighborhood, the predominantly Irish settlement in north St. Louis. As he grew up, he moved up in the local tiers of teams, playing for the St. Louis Peach Pies (which led to his first baseball nickname), then advancing to the very strong semipro St. Louis Shamrocks. The Shamrocks for a time included three future major leaguers: O’Connor and brothers Patsy and George Tebeau.

St. Joseph in the Western League employed O’Connor in 1886 for his first year as a full professional. The Western League in the 1880s was the proving ground for St. Louis-reared ballplayers. No fewer than six St. Joseph players were St. Louisans, including future major leaguers Patsy Tebeau and Charles “Silver” King. O’Connor was the primary catcher for King. When he wasn’t catching, he played both outfield and infield positions. St. Joseph had an impressive season finishing with a record of 50-30, but highlighting the talent level in the league, they still finished four games behind the pennant-winning Denver team.2 The 5’10”, 170-pound O’Connor batted .2703 for the season and impressed at least one Sporting News correspondent who wrote, “John Connors, (sic) of the old Shamrock Club of St. Louis is the acknowledged champion catcher of the Western League. Aside from being a fine backstop, he is one of the best fielders and hardest hitters in the League. He is on the upward road to success.”4

The American Association’s Cincinnati club signed O’Connor in 1887, but the veteran– heavy pennant contenders used him sparingly that season: five games behind the plate and seven games in the outfield. He batted a paltry .100 in 40 at-bats. The team finished an impressive 81-54, but 14 games behind the dominant St. Louis Browns. O’Connor’s fielding ability in the outfield was recognized when he did get a chance to play. The Cincinnati Enquirer noted his play in an August game: “O’Connor maintained Cincinnati’s reputation for good left fielders by catching two very difficult flies, and on another occasion he offset a Metropolitan base hit by getting it back to the infield in time to catch a man away from his base. He is growing to be a decided favorite, and best of all, does not seem to be a man who will get the swelled head.”5

Cincinnati brought O’Connor back for 1888. In the preseason exhibitions he caught with uneven results. In one preseason game against St. Paul, he committed six errors and allowed six passed balls, but just four days later he played flawlessly behind the plate while going three-for-five with a home run. For the season, he was still decidedly a substitute player on a very good veteran team but he did get more playing time. He only caught two league games during the season (committing four errors and allowing nine passed balls). His offense resulted in a .204 average in 137 times at bat. His outfield play was also uneven; he committed 16 errors during his 34 games but he also threw out eight runners. Manager Gus Schmelz was a disciplinarian who did not approve of his players drinking and would fine them $5 when he caught them. O’Connor noted years later, “Of course I was putting in my ante pretty often.”6

The Columbus Solons were a new team in the American Association for the 1889 season. They bought O’Connor from Cincinnati to be their primary catcher. The Cincinnati writers suggested his drinking might impact his ability to keep a job in the major leagues,7 and there was some thought he wouldn’t want to play catcher, but The Sporting News reported in April that he was willing to play behind the plate.8 These concerns proved unfounded because it was a breakout year for O’Connor. He caught 84 games, along with appearing 19 times in the outfield, four at second, and three at first. His batting average was .269 with four home runs in 435 plate appearances. He even stole 26 bases on his young legs.

Columbus reserved O’Connor for 1890 and he wasn’t pursued by the new Players League. He responded by having his best offensive season, batting .324 over 457 at bats. He caught 106 games but kept his utility tag by appearing in 20 more in the outfield and infield. Halfway through the season, his old Cincinnati manager and nemesis Gus Schmelz was called on to manage Columbus and his disciplinary ways drove the team to a 38-13 record after they had started 39-41 under Al Buckenberger. Columbus finished second in the American Association, 10 games behind Louisville.

In 1891, O’Connor’s rowdy behavior on and off the field finally caught up to him. He had played in 56 games and was batting .266 when manager Schmelz and the team suspended him on July 3. Sporting Life reported, “The team suspended Jack O’Connor, the catcher, indefinitely without pay, for conduct unbecoming a gentleman and a ball player. The conduct of O’Connor has been such on the diamond, with assaults and actions toward visiting players that the patronage of the visiting club has been greatly damaged. He has also been drinking to such an extent that he was not able to play his usual game.”9 His nickname “Rowdy Jack” was well earned! O’Connor went to Denver to play for his old teammate and fellow St. Louisan George Tebeau for the Mountaineers in the independent Western Association. He hit .275 while playing outfield in the mile-high air.

Favoritism exists in all workplaces. Cleveland manager Patsy Tebeau recruited his fellow St. Louisan to join the National League Spiders for the 1892 season. O’Connor set career marks by appearing in 140 games and coming up to bat 599 times. This durability was explained in part because he primarily played the outfield, only appearing behind the plate 34 times. He batted a subpar .248 but did play in a postseason series against the pennant-winning Boston Beaneaters. Unfortunately he was only able to secure three singles in 22 at-bats over the series and his team lost five and tied one of the six games in the series.

O’Connor’s offense was unacceptable for a full-time outfielder but he found a home in Cleveland playing for Tebeau. The 1890s are noted for being the most lawless in baseball history. The single official at games was not able to watch the entire field and players ruthlessly took advantage of the official’s inability to cover all the action. Fights were common. Players fought players, managers fought umpires, players fought fans — it was equal opportunity chaos. In this atmosphere, Tebeau and the Spiders were among the leading instigators. And Rowdy Jack fit in perfectly with his pugnacious behavior. He remained on the Spiders through the 1898 season. Tebeau used him as a primary substitute, at catcher and in the outfield. His averages for the 1893-1897 seasons were from .286 to .315 and he became recognized as a reliable and intelligent player, along with being highly competitive and never backing down from a fight. Cleveland was a very good team for most of O’Connor’s seven years. They finished second in the 12-team National League three times and third once, but the team was always near the bottom of the league in attendance — last in 1897 and 1898. O’Connor seemed to thrive on the primary substitute role, as evidenced by his 1898 season. He was called on to play more (primarily at first base and in the outfield) and appeared in 131 games. The extra work resulted in a lower .249 batting average, only one point higher than in 1892.

O’Connor’s offense was unacceptable for a full-time outfielder but he found a home in Cleveland playing for Tebeau. The 1890s are noted for being the most lawless in baseball history. The single official at games was not able to watch the entire field and players ruthlessly took advantage of the official’s inability to cover all the action. Fights were common. Players fought players, managers fought umpires, players fought fans — it was equal opportunity chaos. In this atmosphere, Tebeau and the Spiders were among the leading instigators. And Rowdy Jack fit in perfectly with his pugnacious behavior. He remained on the Spiders through the 1898 season. Tebeau used him as a primary substitute, at catcher and in the outfield. His averages for the 1893-1897 seasons were from .286 to .315 and he became recognized as a reliable and intelligent player, along with being highly competitive and never backing down from a fight. Cleveland was a very good team for most of O’Connor’s seven years. They finished second in the 12-team National League three times and third once, but the team was always near the bottom of the league in attendance — last in 1897 and 1898. O’Connor seemed to thrive on the primary substitute role, as evidenced by his 1898 season. He was called on to play more (primarily at first base and in the outfield) and appeared in 131 games. The extra work resulted in a lower .249 batting average, only one point higher than in 1892.

The Cleveland Spiders won the Temple Cup postseason series against the Baltimore Orioles in 1895, four games to one, but O’Connor did not appear in any of those games. The 1896 Temple Cup was a rematch between the two teams with the Orioles turning the tables and winning four straight. O’Connor played first base during the series and had four singles in 14 at-bats but didn’t tally a run.10 O’Connor’s reputation as a reliable player was fully cemented by this time. The Sporting News, when writing about a trade rumor involving O’Connor being sent to St. Louis, opined, “It is a mighty question whether it would be profitable for the Cleveland team to exchange O’Connor for anybody. Just think of all the sleepy, ‘I don’t care whether I win or lose so long as I get my salary’ players … the opposite of these in ball playing characteristics [is] Jack O’Connor.”11

Stanley and Frank Robison, the Spiders’ owners, bought the St. Louis Browns in a bankruptcy auction in March 1899. Cleveland was the superior team but St. Louis was a larger market, so the Robisons shuffled the players between the two teams, putting all their best men in St. Louis. This shuffle included O’Connor, at least in part because he was a St. Louis native son and because he had expressed interest in playing for his home town team two years earlier.12 He slotted right back into his utility role, but the 33-year-old showed evidence of slowing down. He hit .253 and stole only seven bases, the fewest since his partial rookie season in 1887. The fortified St. Louis team (coined the Perfectos for the season) finished fifth in the twelve-team league with an 84-67 record. The lowly Spiders finished a dismal 20-134 and were eliminated when the National League contracted to eight teams for 1900.

On a personal note, O’Connor married a woman named Cora sometime before 1900. They were divorced in 1905 with O’Connor citing relations with other men, excessive drinking, and smoking. The reporting at the time of the divorce gossiped, “Mrs. O’Connor’s beauty created comment wherever she traveled.”13 No children resulted from this marriage.

The 1900 St. Louis Cardinals (the nickname Perfectos lasted for one season) didn’t have a place for a light-hitting backup backstop. After O’Connor appeared in 10 games, batting .219, the team sold him to the Pittsburgh Pirates for $2,500.14 He played marginally better for Pittsburgh, batting .238 over 153 plate appearances, mostly as a catcher backing up 39-year-old Chief Zimmer. Pittsburgh was a very good team, however, finishing second in the National League with a 79-60 record.

The Steel City brought O’Connor back for 1901 to split time with Zimmer. His .193 batting average was overlooked because the team had big offensive contributions from Honus Wagner, Fred Clarke, and Ginger Beaumont and stellar pitching from Deacon Phillippe, Jack Chesbro, and Jesse Tannehill. Those mighty six were the brawn behind a 90-49 pennant-winning squad.

The 36-year-old O’Connor was having his best season since 1897 for the 1902 Pittsburgh squad. But in August he got himself into trouble. The American League was trying to raid National League players and several of the Pittsburgh stars were targeted. O’Connor acted as a middle man, helping direct unsigned players to meet Ban Johnson and Charles Somers at the Hotel Lincoln. Pittsburgh President Barney Dreyfuss uncovered the scheme and immediately released O’Connor, even though he was hitting .294 at the time. The Pittsburg Press noted that O’Connor was a valuable player and that he must have been paid to help out with the scheme. But the paper also wrote, “The club is better off without a man who cannot be trusted.”15

The American League took care of O’Connor. He played for the New York Highlanders in 1903 with two of his Pittsburgh batterymates, Chesbro and Tannehill. He backed up the forgettable Monte Beville behind the plate, hitting .203 over 225 plate appearances. Many years later, a St. Louis Post Dispatch columnist reported that he was paid $40,000 for that season, which, if true, would have been eight times the salary he received from Pittsburgh the previous year.16 O’Connor did not enjoy playing for New York manager Clark Griffith and in mid-August he refused to show up for a practice. Griffith suspended him (excess drinking also being a factor) and he went back to St. Louis saying he would never play for the New Yorkers while Griffith was in charge.17 In the offseason, New York traded him to the St. Louis Browns for John Anderson.18

Jack Powell, O’Connor’s friend and teammate in Cleveland and St. Louis, married O’Connor’s sister Nora in 1903. They separated in 1907 but O’Connor noted that the domestic difficulties would have no bearing on his friendship with Powell.19

O’Connor’s last employer in Organized Baseball would be the American League St. Louis Browns. There were rumors he would manage the Denver team in the Western Association in 1904 but they were eventually dismissed. From the limited sources, it seems Denver wanted a manager and an investor and O’Connor either didn’t have the capital required or didn’t want to risk his savings on the venture. The 38-year-old was out of shape before the 1904 season, with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporting, “Jack has the genial portly appearance of a prosperous banker, and when he ambles around the park under a few dozen sweaters, he looks as big as a house.”20 He caught a single game in May, but then underwent surgery (possibly for an arm injury) and was out until mid-August. He returned and caught 14 games on the season, all on the road, and hit .213.

Before the 1905 season, O’Connor was in a salary dispute with the Browns. “King” Jack would not agree to a salary cut and instead insisted he would focus on his saloon business located in downtown St. Louis. Reports noted several times that he was ready to play but he never suited up for the team. But he continued to work on his other baseball business skills. In October, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said that “Jack O’Connor . . . is an adept in baseball diplomacy… He bears the reputation of being the best player agent in the profession.” It was implied that he represented players such as Tannehill, Chesbro, and Emmet Heidrick.21

The Browns signed the 40-year-old O’Connor as a backup catcher and de facto coach in 1906. He wrestled his body back into game shape and caught 51 games. He only hit a feeble .190 in 174 at-bats and didn’t manage a single extra-base hit. At this point his reputation as a brainy player and good defensive backstop kept him employed. “Not a little of the fine showing of the Browns this season is due to the work of Jack O’Connor behind the bat, and the difference when O’Connor is catching is so notable that it causes comment among the spectators,” raved the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.22 The Browns finished three games over .500 but fifth in the American League. In 1907, he filled the same role but played less, catching in 26 games and batting .157, although he managed two doubles during the season.

By this time, the media was reporting that O’Connor was a natural to be a manager. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch printed a glowing story about his capability as a manager, noting he stepped up several times in 1907 to manage the team when manager Jimmy McAleer was unavailable.23 This continued in 1908. McAleer was unavailable at the beginning of the year and O’Connor took the helm. He again was highly praised by the media and McAleer.24

O’Connor was strongly seeking a managerial job for the 1909 season but he didn’t apply for the St. Louis Browns job due to his friendship with McAleer. There was a rumor he was pursued by the Boston Red Sox, but nothing came of that. He signed with the Little Rock Travelers in the Southern League to manage and play.25 Again, his managerial skills were praised and he helped his own cause by batting .353 in seven games. There was some controversy over who was really in charge of the team, he or Mickey Finn. Some news stories early in the year referred to O’Connor as the manager but by mid-June he was being called the captain and Finn was the manager.26 Robert Hedges, founding owner of the St. Louis Browns, still considered O’Connor one of his favorites and offered him a chance to come back to St. Louis, but he was constrained by Little Rock. However, this was cleared up at the end of July. Finn shook up the team’s roster, which included granting a release to O’Connor, who then scouted for the Browns for the rest of the year.27

The St. Louis Browns fired Jimmy McAleer after the 1909 season, which cleared the way for O’Connor to manage the team in 1910. The Browns were a terrible team but his managing was praised by the local press. The St. Louis Star and Times opined in July, when there were rumors that Jesse Burkett was going to be the manager in 1911, “With this team of no-accounts, O’Connor has made a mighty fine showing. Don’t we get reports from all over the country stating what daring baseball the Browns are playing, how they are using their noodles for the first time since there has been a Brownie team?”28 During the last two games of the season, however, O’Connor was involved in a controversy which sealed his fate.

Ty Cobb and Nap Lajoie were in a heated race for the batting title in 1910.29 In addition to bragging rights, the Chalmers Automobile Company was offering a new car to the winner. The unofficial batting averages showed Cobb with a nearly insurmountable lead (around .005). Cobb decided to sit out Detroit’s last two games of the season, ostensibly due to an eye ailment, but likely motivated by the batting championship. The Cleveland team and Lajoie had a doubleheader against the Browns but he had almost no chance to get enough hits to catch Cobb.

In the first inning of game one, Lajoie tripled. For the remainder of the game, the Browns’ rookie third baseman, Red Corriden, played deep. Really, really deep. Lajoie bunted, bunted, and bunted some more, racking up three more hits in game one, going four-for-four. It was more of the same in game two. Lajoie successfully bunted four more times. He was also helped out by the official scorer awarding him a sacrifice for his only unsuccessful bunt. The eight-for-eight day robustly padded his batting average and put him (unofficially) just ahead of Cobb.

O’Connor caught the first two innings of the second game, although he originally wasn’t planning to catch. The manager of Cleveland, the venerable Deacon McGuire, was announced as the catcher for Cleveland. O’Connor’s competitiveness got the better of him and he decided to don the “tools of ignorance” himself. He caught the first two innings but took a foul ball off of his hand and decided that was enough for the day.30

O’Connor, who did not like Cobb, was widely blamed by the press of telling his third baseman to play deep against Lajoie, allowing him to easily bunt for hits. One of his coaches, Harry Howell, was also highlighted for going to the official scorer and offering him a new suit for their “proper” scoring during the game. O’Connor denied any wrongdoing, noting that he was having Corriden play deeply to protect him from Lajoie’s vicious line drives. American League president Ban Johnson investigated the incident and absolved Corriden, allowing the statistics from the games to stand. When the official batting averages were released, Cobb was declared the winner .385 to .384 for Lajoie.31 The Chalmers Automobile Company gave cars to both men and reaped the rewards from a mountain of free publicity.

Although O’Connor wasn’t officially punished by the league, Browns owner Robert Hedges fired him and he was blackballed by Organized Baseball. Since he had a signed contract to manage the Browns in 1911, he successfully sued the team for the $5,000 remaining on the contract. The judge found that since the evidence didn’t exist to prove he ordered the player positioning on defense, there was no legal reason for the Browns to not pay the contract.

In 1912 O’Connor managed the Cleveland Forest Cities of the independent but short-lived United States League and in 1913 he managed the St. Louis Terriers of the independent minor Federal League. On June 30, living up to his competitive reputation, he got into a fist fight with umpire Jack McNulty and broke his jaw. The Federal League suspended him; he paid a $1200 settlement, and was shortly reinstated as manager.

He scouted a bit for the St. Louis Terriers in 1914 but that was his last employment in baseball.

O’Connor ran a saloon and did some boxing promotion after his baseball career ended. He also married his second wife, Sadie Le Roy, after his baseball career ended.

O’Connor died at his home at 2043 East Obear Avenue in St. Louis on November 14, 1937. He had been in poor health for a time with a litany of problems, including rectal cancer, heart disease, and pneumonia. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.

In an interview with The Sporting News four years before he died, he still didn’t admit any blame but expressed regret over the Lajoie/Cobb controversy. He was quoted, “I might have been well fixed today, perhaps still in the game, had I smashed that thing before it had a good start” which frames his role in the controversy as a bystander. Later in the same interview he said, “I wish I had it to do all over again.”32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and Newspapers.com.

Notes

1 Documents differ as to the actual date of birth. This is the date in Baseball Reference. However, in at least one obituary, his birth date is listed as March 3, 1867. And his death certificate implies June 2, 1869.

2 “The Western League,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1886: 3.

3 “The Western League,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1886: 3.

4 “Grether and King,” The Sporting News, August 23, 1886: 1.

5 “Nearly Second,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 2, 1887: 2.

6 Dick Farrington, “O’Connor Looks Back at Lajoie’s ‘8 Hits,’” The Sporting News, February 23, 1933: 3.

7 “Another Recruit,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 10, 1889: 2.

8 “The Columbus Club,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1889: 2.

9 “O’Connor Suspended,” The Sporting Life, July 4, 1891: 1.

10 O’Connor’s Temple Cup statistics from Baltimore Sun in October, 1895 and October, 1896.

11 “Alleged Deal,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1896: 2.

12 “Gossip By The Players,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1897: 2.

13 “Jack O’Connor Sues His Wife,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 25, 1905, 3.

14 “Gossip of the Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 23, 1900: 5.

15 “Wagner Rejects Fortune,” Pittsburg Press, August 21, 1902: 10.

16 John Wray, “He Did Pretty Well,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 17, 1937: 4B.

17 “Jack O’Connor Defies Griffith,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 23, 1903: 12.

18 “Catcher O’Connor Returns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 30, 1903: 4.

19 “Jack Powell Quits His Wife,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 14, 1907: 1.

20 “Powell and Burke Working Off Fat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 9, 1904: 6.

21 “Hedges Wants N. Elberfeld,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1905: 6.

22 “Most Important Man on Ball Team is One Who Does the Catching,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 1, 1906: 45.

23 “One of the Grand Old Men of Baseball,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 25, 1907: 13.

24 “M’aleer Back; Rube Picked for Opener,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1908: 16.

25 “Browns to Appear At Traveler Park,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), March 11, 1909: 10.

26 “Carey May Help Out Travelers,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), June 14, 1909: 6.

27 “Manager Finn Shakes Up Team,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), August 1, 1909: 9.

28 JLL, “O’Connor Has a Team of Misfits. Give Him Some Real Ball Players,” The St. Louis Star and Times, July 23, 1910: 10

29 The story of Cobb and Lajoie’s batting controversy was pulled largely from stories printed in The Sporting News and St. Louis Post Dispatch accounts of the games and the aftermath.

30 “Mere Baseball Loses Interest in the Face of Lajoie’s Stickwork,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 10, 1910: 8

31 After research by many parties over the years, per www.baseball–reference.com, the current batting average for Lajoie is .383 and Cobb is .382. The batting title officially remains with Cobb since he was awarded it at the time by the league.

32 Dick Farrington, “O’Connor Looks Back at Lajoie’s ‘8 Hits,’” The Sporting News, February 23, 1933: 3.

Full Name

John Joseph O'Connor

Born

June 2, 1866 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 14, 1937 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.