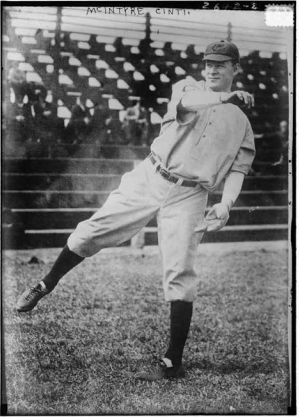

Harry McIntire

Harry McIntire played professional baseball from 1900 through 1913. After spending five years in the minor leagues, he ascended to the major leagues with Brooklyn in 1905. Over the next five seasons McIntire toiled in futility with Brooklyn. In 1910, he was traded to the Chicago Cubs. Though pitching in a diminished role, he had his greatest success there, including making a World Series appearance in 1910. A decent-hitting pitcher and spitball specialist, “Handsome Harry” once pitched no-hit ball for 10⅔ innings before losing 1-0 in 12 innings. More ignominiously, McIntire had the unenviable distinction of losing 20 or more games in a season three times in his career, all with Brooklyn. After baseball, McIntire lived a vagabond life of a professional golfer, scout, gambler, and idle fisherman.

Harry McIntire played professional baseball from 1900 through 1913. After spending five years in the minor leagues, he ascended to the major leagues with Brooklyn in 1905. Over the next five seasons McIntire toiled in futility with Brooklyn. In 1910, he was traded to the Chicago Cubs. Though pitching in a diminished role, he had his greatest success there, including making a World Series appearance in 1910. A decent-hitting pitcher and spitball specialist, “Handsome Harry” once pitched no-hit ball for 10⅔ innings before losing 1-0 in 12 innings. More ignominiously, McIntire had the unenviable distinction of losing 20 or more games in a season three times in his career, all with Brooklyn. After baseball, McIntire lived a vagabond life of a professional golfer, scout, gambler, and idle fisherman.

John Reid “Harry” McIntire was born in Detroit on January 11, 1878.1 Further confusing matters, his last name was variously spelled McIntire or McIntyre throughout and after his playing career.

Research found no early census records or other early documentation about McIntire’s childhood, except for a newspaper article published in 1910.2 In that article, McIntire described his early childhood and discovery of baseball. His recollections went to his youth, when he expressed an interest in being a locomotive engineer or priest. He became fascinated by baseball at a young age, participating in pickup games anywhere he could.3

McIntire played his first organized baseball at the Brothers’ School in Dayton, Ohio. He described his first position as, “back up for the catcher and very proud to chase balls that went past him.”4 Taking an interest in pitching, he worked with one of the priests to practice his craft. He noted that one of the great lessons he’d learned was that “keeping cool and never losing the temper was a better way of winning than pitching curves.”5

McIntire said that when he graduated and began looking for work, a friend told him that the YMCA team in Kankakee, Illinois, was looking for a pitcher. McIntire pitched for the team for a couple of summers, honing his craft.6 In 1900, at 22, he played his first season of professional baseball, for Danville, Illinois, of the Central League. Full pitching statistics aren’t available for that season, but Baseball-Reference credits McIntire with 47 games played.

McIntire played part or all of five seasons in the minor leagues. After Danville he

pitched for the 1901 Toledo Mud Hens in the Western Association. That team finished in third place, with a 78-60 record, six games out of first place. McIntire pitched in 25 games and also played in the outfield. For the season, McIntire batted .313 in 176 at-bats, with 12 doubles, 3 triples, and 9 home runs.

On the move, McIntire played for three teams in the Southern Association in 1902, Shreveport, Nashville, and Memphis, pitching in 16 games (4-7) and playing 25 in the field.

In 1903 and 1904 McIntire stayed in Memphis, compiling records of 20-15 and 19-8 respectively. His batting statistics fell off however, with batting averages of .185 and .215. He caught the attention of the Brooklyn Superbas, who signed him after the 1904 season.

McIntire began his career inauspiciously, making his debut in a relief appearance on April 14, 1905. He was shellacked for six runs in four innings pitched. On the 18th he made his first start, facing Boston. Though he lost the game, he allowed just two runs, both unearned, in eight innings pitched.

Next, McIntire pitched two gems, blanking Boston 4-0 on the 22nd and then defeating the Giants 3-2 on the 26th. Of the latter game, the Brooklyn Eagle correspondent wrote, “Harry McIntire was the hero of it all. It took a mighty swipe of the ball to bring him fame, but he was equal to it.”7 In that game McIntire defeated Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity. This was made into a big deal in Brooklyn, whose team had not defeated McGinnity the season before. So glorious was the victory that in the Eagle an aspiring poet wrote:

The score stood one to nothing when the Giants came to bat,

But a lightning sort of rally soon slightly Altered that.So when the Brooks came to the plate and Ritter got his base

No one supposed that McIntire was even In the Race.There was blood in Harry’s optic as he whaled the ball with wrath

And wings on Ridder’s pedals as he flew around the path.“The score is tied!” the rooters yelled, “now beat ’em at the wire.”

And Lumley made a star of McIntire.That’s why all things are bright, although it’s raining here to-day.

And joy and jest are unconfined, the fans are blithe and gay.The “Iron Man,” the only one, was beaten Out, you see.

For the first time by our warriors, since 1903.8

Unfortunately for McIntire, April 26 marked the apex of his season. He followed his winning performance with a loss to Philadelphia on May 2. On the 9th, McIntire pitched a no-decision versus the Cincinnati Reds and he defeated the Pirates on the 13th. McIntire did not win again until June 30, though he didn’t pitch badly. On June 7 he was defeated by the Reds, 5-4. The Eagle wrote, “Starring in their exclusive sketch, ‘Beaten at the Finish,’ the Superbas lost the opening spiel with the Reds.”9

On June 30 McIntire defeated the Giants, 6-5 and on July 4 he defeated Boston, 2-1. The New York Tribune reported, “The feature of the afternoon game was McIntire’s home run drive to centre field in the third inning. With the hit, he practically won his own game.”10 Another prolonged slump ensued.

On July 29, the Eagle reported, “Opposed to Deacon] Phillippe at the start was McIntire, but the Pirates jumped all over him, and after two innings of dreadful bombardment he was removed.11 Compounding McIntire’s erratic pitching was the awful fielding of his teammates. On September 7, he was defeated by Philadelphia 5-4. The Eagle reported, “McIntire was opposed by Bill] Duggleby and there was little to choose between the pair, but the support of the latter was much more steady. Five errors were charged against the Brooklynites.”12

By season’s end McIntire had lost 25 games, winning 8. In 40 games pitched, he started 35, completing 29 and pitching 308⅔ innings with a 3.70 ERA. His 101 walks and 20 hit batters (a league high) portended a wild streak he maintained through his career.

Such was the futility of Brooklyn baseball that 25 losses still earned McIntire the 1906 home opening start. And he pitched well enough to win, except that he didn’t, losing to Boston 2-0. He struck out 10 and surrendered six hits in a complete-game performance. Throughout April McIntire pitched well but was winless. Sloppy play continued to mar his performances, though he also was not immune to it himself. Of a loss to New York on April 20, the Eagle correspondent wrote, “McIntire’s muff at the plate started the champions mauling with a couple of runs they should never have scored. … [He] can blame nobody but himself for the one-sided aspect of the score.”13

After his slow start, McIntire won about as much as he lost from May onward. On May 30 the Eagle, reporting on his 2-0 victory over the Pirates, wrote, “Harry McIntire, who was credited with yesterday’s victory in Pittsburgh, kept up his superb form by holding them down to four scratched hits.”14

Continuing his strong pitching, on August 1 versus the Pirates, McIntire put on a remarkable performance in a losing effort. The Eagle reported:

“Local base ball history fails to parallel the game played by the Brooklyns and Pittsburgs at Washington Park yesterday. Thirteen innings in which only one run was scored and where the losing pitcher held the visitors without a solitary hit for nearly eleven innings, is a performance that will take its place at the top of the remarkable events of the national sport. Harry McIntire was the unfortunate twirler who holds the distinction of pitching a no-hit game for ten and two-thirds innings and still suffering defeat.

Followers of base ball are not surprised over McIntire’s misfortune in losing the best game of his career. He has been known as the champion hard luck pitcher since he broke into the league. Not long ago, he held Chicago down to no hits in eight innings and lost out in the ninth on one single.”15

That day, McIntire pitched 13 innings, losing 1-0 when his no-hit game was broken up by Claude Ritchey.

By season’s end McIntire had completed a second successive 20-loss season, this time finishing 13-21, despite a solid ERA of 2.97. He pitched in 39 games, starting 31 and completing 25 over 276 innings.

McIntire continued his hard-luck pitching through the 1907 season. On August 24 he started against St. Louis. Wrote the Eagle, “Harry McIntire handicapped himself at the start of the first game by a sensational stop of a terrific liner from Bobby] Byrne which he beat down and threw to first in time. The drive broke a small bone in Mac’s left hand, but he did not pay any attention to it.”16 He missed several starts, and perhaps it was a blessing in disguise as McIntire’s season did not end in another 20 losses.

By season’s end McIntire finished with a record of 7-15 in 28 games. His ERA was a career-best 2.39. Even outside Brooklyn people took notice of McIntire’s plight. On October 6, the Chicago Tribune noted, “The pitchers who deserve the hard luck laurels for losing games after holding their opponents … are Nat] Rucker, Elmer] Stricklett and McIntyre.”17 (All three pitched for Brooklyn.)

While McIntire was thought of as a hard-luck pitcher, by 1908 his losing record found increasing critical notice locally. Of On June 24 the Eagle wrote, “Both sides used two pitchers, Harry McIntire being the first to retire, and Lew] Moren following soon after. McIntire was an open book to the visitors, who … recovered their slugging abilities.”18 On the 30th the Eagle reported, “The Giants took kindly to the slants of McIntire. … Manager Patsy] Donovan very promptly and properly chased Handsome Harry to the clubhouse.”19

Even in victory the Eagle correspondent took a swipe at McIntire when he wrote, after a 6-2 defeat of Cincinnati, “McIntire was in good form, being steadier than usual.”20 Despite the results, McIntire was pitching effectively. In fact, by midsummer he boasted, “I’ll pitch another no-hit game before the season is over.”21 That was not to be. The 1908 season was the third 20-loss season in McIntire’s four years with Brooklyn. While his record was an anemic 11-20, he pitched four shutouts, and his retrospective WAR (Wins Above Replacement) was a career-best 3.2.

Early in the 1909 season McIntire helped Brooklyn defeat a pesky Boston nine. The Pittsburgh Sun wrote, “Brooklyn put an end to Boston’s winning streak this afternoon through the excellent twirling of McIntire and some timely hitting by the men behind him. … Additional credit is due McIntire because some of the fielders … played raggedly in the afternoon.”22 But his season record was 7-17, and his ERA rose to 3.63.

McIntire spent January 1910 visiting Texas. During a stay in El Paso, a local paper reported that he attracted attention at the local bowling alley and the YMCA, where the memory of Christy Mathewson and his checker playing was still fresh, and he ‘rolled ’em down the other alley, pally,’ until the pin boys had paralysis in their arms. …”23

The article went on to discuss the coming season. McIntire may have had an inkling of changes; the paper reported, “Being sewed up in a contract with Brooklyn, he does not know yet what his immediate future will be. ‘I may be traded, retained or sold by Brooklyn,’ he says. ‘It all depends on the outcome of the meeting in New York as to which of the National League teams I play with next season.’ Judging from his record of last year, the man from Babybuggyville is due to make good. …”24

About the same time, new Brooklyn manager Bill Dahlen was sanguine about his team’s prospects. Dahlen said, “I don’t really believe that I hope to look for a championship team this year. My sole ambition is to give Brooklyn a winning team. … Do I think I have a good pitching department? Of course it could be made stronger; but I am satisfied. I bank on Rucker and McIntire.”25

Despite Dahlen’s hopes, on April 9 McIntire was traded to the Cubs for three minor-league prospects, Tony Smith, Happy Smith, and Bill Davidson. “Brooklyn has figured in several deals in major league baseball, but the trade arranged yesterday by Manager Dahlen appears to be the best that has ever been pulled off,” wrote the Eagle. “… While Brooklyn has undoubtedly made a trade that will be of great benefit to the local team, still Harry McIntyre will be greatly missed, not only by the club but by the local fans. Of all the hard luck twirlers that Brooklyn ever had, Handsome Harry had more than his share last season and even before that.”26

Another newspaper opined, “Charles W. Murphy, president of the Chicago Cubs, gave Tony Smith, Happy Smith and Davidson, three promising youngsters, for McIntyre, the Brooklyn pitcher, just because the twirler always has had the Buffalo sign on Pittsburg. One report says Murphy gave $7,000 to boot. Shows how bad Chicago wants to beat Pittsburg.”27

McIntire did not disappoint. While not spectacular, he fashioned a good season. Writing of McIntire’s 1-0 victory over Pittsburgh, the El Paso Herald reported on April 28, “The best piece of news was the performance of Harry McIntyre with the Cubs. In the one to nothing game with Pittsburg, Harry worked the well-oiled machine. … His work against the world champs was spoken of in the telegraphic reports of the game as brilliant and it looks as if Harry was due to lose the title of the hard luck pitcher of the major leagues.”28

Soon McIntire may have felt as though he was back in Brooklyn. On May 12, he lost to New York, and while he surrendered five runs in seven innings, the Cubs backed him with seven errors.

On September 29, McIntire defeated Boston 8-3. Wrote the Chicago Tribune, “Chicago Cubs crept nearer the inevitable today. … McIntire was selected to do the honors and held the Doves safe after a bad start. …”29

Chicago won the pennant going away, with a 104-50 record, 13 games in front of the second- place New York Giants. They met the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series and lost in five games. McIntire was moved to a bullpen role in the Series and made two appearances. In Game One he relieved Orval Overall in the fourth inning and pitched five innings of one-hit ball, surrendering one unearned run. Philadelphia won, 4-1. In Game Three, he relieved Ed Reulbach in the third inning. He was hit hard and in one-third of an inning he gave up four runs, taking the loss.

On a pitching staff featuring Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, King Cole, Overall, and Reulbach, McIntire held his own. Because the Cubs were so deep in pitching, he was not called on to pitch an extravagant number of innings. McIntire finished the season with a 13-9 record with a 3.07 ERA in 176 innings pitched (19starts). For McIntire, enjoying his first winning record in the majors and pitching in the World Series must have felt very satisfying.

Then 33, McIntire entered the 1911 season hopeful for more. He started off positively. On April 18, the Chicago Tribune wrote, “One of the pleasing features of the game was the pitching of Harry McIntire. He showed more yesterday than he showed at any time last year. He looked as good as he ever did when he was about the only star on the Brooklyn club. He had his old side arm delivery, was hooking over curves, shooting fast ones … all with the ease and grace of a master of the game.”30 McIntire pitched a complete game in his first start, on April 17, giving up only two unearned runs on six hits in a 7-2 victory.

Throughout the year McIntire pitched adequately and was winning consistently, but getting into games more sporadically than in the past. His season record was 11-7. However, he pitched in only 25 games, the fewest of his career to date. He started 17 games and had a 4.11 ERA.

McIntire’s 1912 season consisted of four appearances. It was alleged that he came into camp out of shape. However, in his April starts he pitched well. On April 12, he lost to Cincinnati 3-2 in 10 innings. The Tribune wrote, “Up to the tenth innings McIntire outpitched Rube] Benton by considerable. The Reds were able to get only five hits off the side arm spitter.”31 On April 25 he defeated the St. Louis Cardinals, 5-2. On May 2, McIntire lost to Pittsburgh 6-0, surrendering four runs in 2⅔ innings. In that same series, he slugged a pinch-hit triple.

By June 21 McIntire had been sold to Milwaukee of the American Association; his major-league career appeared to be over. However, McIntire never appeared with Milwaukee, and Milwaukee rescinded the deal because McIntire was not in shape.32

For Chicago McIntire’s won-loss record was 1-2. He did not give up. He worked hard to get in shape over the winter.

Joe Tinker became the Cincinnati manager in 1913. According to the Pittsburgh Press, he brought several Cubs teammates with him to Cincinnati, in part to be with familiar faces. One invitee to spring training was McIntire.33

McIntire made the team, and came north. However, his stay was brief, He made one appearance with the Reds, pitched one inning, allowed three runs and took a loss. Shortly afterward he was released.

After his baseball career, McIntire nearly disappeared, but not entirely. He settled first in Louisiana, and then Florida. Applying for a passport in 1919, he noted that he had been residing in Hammond, Louisiana, for four years. His stated reason for making the application was to scout ballplayers in Cuba. It is unknown with which team he may have been affiliated.

In the 1920 US Census, McIntire still listed Hammond as his home. He stated that he was married, and listed his occupation as ballplayer.

Insight is gained about McIntire in a 1970 correspondence between Wilbur S. McIntire, Harry’s nephew, and Colonel Jack W. Rudolph. The nephew wrote,

“I suppose that you would have to consider John Reid (McIntire) definitely a ‘loner.’ Many of the years of his life were unknown to his immediate family. It can be said that he never ‘worked a day in his life.’ To a great extent he made his way by gambling. For instance in the late ’30’s, I was playing with a band … at the Eagles picnic grounds near Dayton, on which was situated a private gambling club. … I had occasion, without good cause, to visit the establishment. Upon entering the door, here was my Uncle John, running a roulette wheel. (Out of Chicago).

“At one time he was engaged by one of the ‘sugar kings’ to fly with him to Cuba to participate in a poker game. The stakes in this game were the highest in the history of this country. The family tells that he came back to the U.S. with $60,000.

“I do know that sometime near 1940 he married an extremely wealthy widow from Louisiana. During this time, or prior to 1938, he was a pro in golf and gave lessons in Florida. You can see the information is very vague.”34

It appears that McIntire married twice. In his World War I draft registration form, dated September 12, 1918, he identified Mrs. Nellie McIntire as his next of kin. It does not appear that he had children.35 McIntire was survived by two brothers Will and Frank, and a sister, referred to as Mrs. Walter Payne.36 After his death, on January 9, 1949, his estranged family took care of his burial in Dayton, Ohio. They were the ones who listed his birthday as January 11, 1879, and birthplace as Dayton.37

John Reid McIntire was an enigma to many. His nephew’s sketch paints the picture of a restless soul, on the fringe of society. But his steady residences in Louisiana and Florida belie that perception. Perhaps he was not constituted to work 9 to 5. Because of his estrangement from family, the picture of McIntire painted by his nephew should be taken cautiously.

McIntire played professional baseball in all or part of 14 seasons, nine in the major leagues. In five seasons with Brooklyn he established a record of futility hard to imagine, losing 20 or more games in three of those years. Labeled a hard-luck pitcher, McIntire performed at or slightly better than the league average over his career. A testament to that is his winning record in the two full seasons he pitched for a stronger club in Chicago. Ironically, he enjoyed that success during a time of diminishing skill.

Standing 5-feet-11 and weighing in at 180 pounds, he threw right-handed and was best known for his side-arm spitball. McIntire finished his career with a 71-117 record. He compiled a 3.22 ERA in 1,650 innings pitched. Over his career he had 17 shutouts.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Notes

1 It is often reported that McIntire was born in Dayton, Ohio, on January 11, 1879. However, he consistently described his birthdate as January 11, 1878, in the census, and on passport application and draft registration forms. See, for instance, passport application, January 11, 1919, Louisiana, county of Tangipahoa. The purpose of application was, “To look over ground for securing ball players” in Cuba. He also consistently described his birthplace as Detroit, Michigan, in those same documents.

2 “His Career Was Accidental,” Huntington Park (California) Daily Signal, October 11, 1910: 7.

3 Ibid. Searches for more information on McIntyre’s family turned up a John R. McIntire (carpenter contractor) and a John K. McIntire (insurance agent) in the Dayton area. It is not clear if either (or perhaps another person) was Harry McIntire’s father.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 27, 1905: 11.

8 “Baseball Notes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 27, 1905: 11.

9 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 8, 1905: 10.

10 New York Tribune, July 5, 1905: 11.

11 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July30, 1905: 43.

12 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1905: 10.

13 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 21, 1906: 10.

14 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 30, 1906: 3.

15 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 2, 1906: 3.

16 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 25, 1907: 35.

17 Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1907: 35.

18 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 24, 1908: 22.

19 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 30, 1908: 20.

20 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 18, 1908: 20.

21 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 4, 1908: 3.

22 Pittsburgh Sun, April 20, 1909: 7.

23 “Big League Pitcher Visits the City,” El Paso Herald, January 11, 1910: 4.

24 Ibid.

25 “Manager Bill Dahlen Predicts a Successful Season for Brooklyn Infants,” Pittsburgh Press, February 7, 1910: 12.

26 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 10, 1910: 16.

27 Donaldsonville (Louisiana) Chief, May 21, 1910: 7.

28 El Paso Herald, April 28, 1910: 5.

29 Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1910: 12.

30 “McIntire Shows Real Class,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 18, 1911: 22.

31 Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1912: 8.

32 “McIntire’s a Brewer,” Elyria (Ohio) Chronicle Telegram, June 21, 1912: 6.

33 “Harry McIntire Will Be Tried by the Reds,” Pittsburgh Press, January 26, 1913: 20

34 Baseball Hall of Fame library, player file, correspondence between Wilbur S. McIntire and Col. James W. Rudolph, June 8, 1970.

35 Draft registration, September 18, 1918.

36 Baseball Hall of Fame file, John Reid McIntire, correspondence between Col. Jack W. Rudolph and librarian Mrs. Joseph “Frances” Casey, Winchester Community Library, April 15, 1970.

37search.ancestry.com/cgibin/sse.

Full Name

John Reid McIntire

Born

January 11, 1879 at Dayton, OH (USA)

Died

January 9, 1949 at Daytona Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.