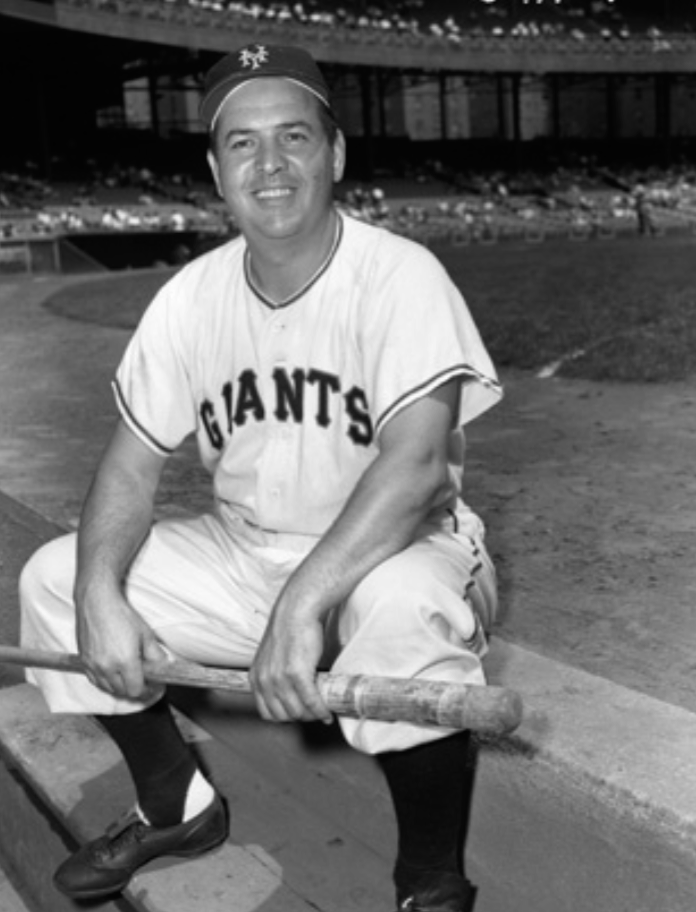

Herman Franks

The Dodgers had another chance to stop the Yankees’ World Series winning streak at nine games. Brooklyn had blown a golden opportunity to at least tie New York in the top of the seventh but Pee Wee Reese ran into an out and Dixie Walker’s subsequent groundout ended the threat. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher was looking for another chance as well. He was not having a good game from the dugout. In the fifth, he did not pinch-hit for his starter with a runner on third, only to replace him four outs later when down another run. A missed bunt sign (did Durocher give it?) led to the rally-killing double play in the seventh. Now, in the ninth, down 3-2, Durocher and 68,540 spectators were not going to see All-Star catcher Mickey Owen hit with two on and one out. No, Durocher had sent in Lew Riggs to hit for Owen in the fateful seventh despite Owen’s having had a run-scoring triple off Yankees starter Red Ruffing earlier in the game. Instead, the multitudes were looking at backup catcher Herman Franks, with his .201 batting average in limited action. The Dodgers were carrying only two catchers. Franks had to hit. If he came through, Dodgers fans would forgive Durocher’s missteps. The baseball press might be a bit more forgiving. Unfortunately for Durocher and the Dodgers, Franks, swinging at the first pitch, sent a hard grounder to Joe Gordon at second. From there it was virtually automatic. Gordon to Rizzuto to Sturm and Game One of the 1941 World Series went to the Yankees. It was to be the only World Series appearance of Franks’ career and it was six years before he next saw major-league action.

Herman Louis Franks was born on January 4, 1914, to Edith and Celeste Alfonzo Franks (née Franch). The elder Franks, a photographer from the northern Italian village of Cloz, was 32 when he married the 18-year-old Coloradan Edith Dozzi, a coal miner’s daughter of Italian descent. After the marriage, the pair moved to Price, Utah, a small but fast-growing city 120 miles southeast of Salt Lake City. Herman was born in Price and spent the first six years of his life there, until his parents divorced in 1920. Celeste left for Nevada. Edith and Herman moved to Salt Lake City, where she established a grocery store and later a beauty salon. Mrs. Franks encouraged Herman to participate in athletics and he showed prowess at an early age. By 14, he was playing in men’s baseball leagues. He was a four-sport (baseball, basketball, football, and track) standout at East High and, as he neared graduation in 1931, he was offered contracts and scholarships from the likes of the New York Yankees and the University of Notre Dame. Franks chose to remain close to his mother however, and enrolled at the University of Utah for the fall semester.

Franks played football, wrestled, and ran track in college. The lure of money proved too great, and he left the university in the spring of 1932 to play for the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. The Stars, managed by former major-league infielder Ossie Vitt, were loaded with once and future big-league players, very fast company for the 18-year-old left-hand-hitting catcher. Franks made his debut with the Stars on March 27, 1932, in an exhibition game against a Marine Corps team. He acquitted himself well enough to earn a subheading in the Los Angeles Times game account: “Kid Catcher Impressive in Work Behind Bat.” The story included a short paragraph about Franks, mentioning that he was under contract, had been with the team only a few days, and would remain in Los Angeles during the season; i.e., the teenager would not be traveling with the grizzled veterans.1

Franks got into only four games with the Stars in ’32, garnering three hits in eight at-bats with a home run. Former major-league catcher, Johnny Bassler, at 38, yielded some catching time to teammates in 1933 with Franks the beneficiary for 16 games. He played well as a receiver and hit .306 (11-for-36) with three doubles and a home run. In his home-run game, against the San Francisco Seals, Franks had three RBIs, but he had to share the spotlight with a player 11 months his junior, Joe DiMaggio, who hit two homers in a losing effort.

Franks showed, at least with this limited sample size, that he could hit PCL pitching, but the 19-year-old needed experience (“more seasoning” in the parlance of the day). It was likely a disservice to the youngster to have him under contract in the high minors when he should have been an everyday player in the bushes. The year 1934 was a lost one for Franks’ baseball career. He played, at least part of the season, for the East Side (Los Angeles) Brewers, a club in the semipro Southern California Baseball Managers’ Association. By early July though, he was playing for the Omaha Packers in the Class A Western League (still fairly high minors for a 20-year-old with very few minor-league at-bats). He played in just two games for the Packers, going 1-for-3 with a triple.

Franks entered the St. Louis Cardinals’ famed farm system in 1935 and finally got the playing time he needed. The young catcher found himself in Jacksonville, Texas, playing in the Class C West Dixie League. He played in 128 of Jacksonville’s 132 games, catching 124 of them; he hit .284 with six homers and 24 doubles for the fourth-place Jax. (The Jax won the West Dixie playoffs, becoming the last champion of the circuit, forced under by the Great Depression.) The Cardinals promoted Franks to the Texas League, where he shared the catching duties with future American Leaguer Bill Conroy and also was a teammate of future major-league manager Johnny Keane. For the second-place Houston Buffaloes, Franks hit .260 with little power. He started the 1937 season with the Buffaloes but after ten games he was back in the PCL, this time with a St. Louis affiliate, the Sacramento Solons. After six years in the minors, Herman was back where he started, albeit with a different franchise. Franks caught 89 games for the Solons, 24 more than teammate Walker Cooper, while hitting .265 with 22 extra-base hits.

For his seventh minor-league season, Franks was back in Sacramento, a team that had gone from worst to first in the last two seasons for manager Reindeer Bill Killefer, It was perhaps Franks’ finest professional season. The 24-year-old “veteran” hit .274 in 143 games against the highest minor-league competition, with 29 doubles and 9 home runs. Franks caught 131 games, making just seven errors in 646 chances. The Solons finished third in the regular season, then defeated the San Francisco Seals four games to one in the playoff finals.

At the PCL meetings in San Francisco that November, Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey was present as a visitor. He took the opportunity to tell The Sporting News “he was taking catcher Herman Franks … to Cardinal training camp [for 1939].”2

In spring training, the 1939 Cardinals had 23-year-old future All-Star and MVP candidate Mickey Owen as their number-one backstop, but the number-two position on the depth chart was wide open. The Cardinals were attempting to convert to catcher their outfielder Don Padgett, two years removed from hitting .314 as a rookie. Franks had to compete against Padgett and a couple of other rookie receivers. He made the Opening Day roster and, at age 29, made his major-league debut on April 27, 1939, against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Sportsman’s Park. He batted for pitcher Bob Bowman in the bottom of the ninth, drawing a walk. Owen had been hit for in the ninth as well, so Franks stayed in the game defensively. In the bottom of the 11th with Don Padgett, at second, Franks hit a grounder to Pirates second baseman Pep Young. Young bobbled and the hustling Herman beat the throw, allowing Padgett to score.

Franks’ first major-league hit came in his first start, on May 2, 1939, at Braves Field in Boston. The 5-foot-10, 187-pounder, just the ninth native of Utah to play in the majors, singled in his first at-bat off Bees starter Danny MacFayden, driving in Johnny Mize. It was the first run in an eventual 2-1 Cardinals victory. But Franks injured his ankle getting back to first while avoiding a pickoff attempt and was out of the lineup for 22 days. Between May 24 and July 2, he appeared in 12 games, including two starts, but could not deliver another hit. On July 8 he was optioned to the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds. Franks hit .297 there in 58 games and made just three errors.

The 1939 Brooklyn Dodgers had relied on 31-year-old left-handed-hitting Babe Phelps to perform most of the catching duties. Al Todd, 37, started 59 games, and two other players saw action behind the plate as well. Perhaps Brooklyn wanted more power than Phelps or Todd could provide (44 extra-base hits between them) or maybe the Dodgers wanted to get younger. In February 1940 GM Larry MacPhail purchased Franks’ contract from the Cardinals for a reported $25,000.3 The New York Times article describing the transaction said Franks was “highly regarded as a left-handed hitter.”4

After a slow start in spring training because of a thumb injury, Franks had a spectacular regular-season debut with the Dodgers. On April 23, 1940, the Dodgers took on the Boston Bees at Ebbets Field. Franks was the starting catcher (Phelps was nursing his own thumb injury) and batted seventh just ahead of rookie shortstop Pee Wee Reese In his first Brooklyn at-bat, with two on and two out, Franks hit a Nick Strincevich offering over the right-field fence onto Bedford Avenue, tying the game. He also had two singles, a double, and three RBIs, helping Brooklyn to an 8-3 victory. After yielding for one game to 34-year-old veteran Gus Mancuso, Franks started again on April 25,went 2-for-4 with an RBI and helped the Dodgers beat the Phillies for their fifth consecutive win to start the season.

Franks sat against the Phillies’ Lefty Smoll but started the next two games against the Giants at the Polo Grounds and went just 1-for-8 at the plate. The Dodgers, however, continued to win as they traveled to Cincinnati on April 29. Although Phelps was ready to return, Durocher stuck with his hot lineup, which meant Franks was behind the plate for his third consecutive start and in a prime location to be a key part of some baseball history. A win would give the Dodgers their ninth consecutive victory to start the season, tying the modern major-league mark. The win, if it came, would come at the expense of the powerhouse Reds, reigning NL champs who were on their way to another pennant and their first World Series title since the tarnished 1919 crown. The Dodgers did win and they won with style. Their starter, Tex Carleton, allowed two free passes but nary a hit as the Dodgers won 3-0. Franks was flawless behind the plate including gunning down Reds third baseman Billy Werber on the basepaths. He was hitless himself but did walk and scored the first Dodgers run, the only one his batterymate would need.

The magic was not to last, however. The Dodgers faced the 1939 NL MVP Bucky Walters the next day and lost to the dominating right-hander, 9-2. Franks had a single in two trips to the plate before being replaced by pinch-hitter Babe Phelps in the sixth. After that he was relegated to pinch-hitting, late-inning defensive replacement, and the occasional start. Franks took a .300 average into a start on May 21 against the Cubs in Brooklyn but went 0-for-3 and never reached that benchmark again that season. In fact, his average continued a steady decline as the season progressed, finishing near his low-water mark, .183 (24-for-131). Overall, Franks played in 65 games for the second-place Dodgers, the most he ever played in the majors.

Brooklyn was not content to rely on Babe Phelps as its first-string catcher. Phelps, the last of Casey Stengel’s Daffy Dodgers still with the team, was a malingerer in Durocher’s eyes. Phelps, likely suffering from neurasthenia, was a hypochondriac at least. On December 4, 1940, the Dodgers sent Gus Mancuso, a minor leaguer, and $65,000 to the Cardinals for Franks’ former teammate, the 24-year-old Mickey Owen. The fiery Owen, for his part, wanted more money from MacPhail than MacPhail was prepared to pay and was a holdout when the Dodgers traveled to Cuba for spring training in 1941. Phelps, too, balked at going to Havana, claiming influenza. With the paucity of catchers, Franks became the de-facto number one, at least in the early part of the preseason. With Durocher regularly sending in substitutes for every position except for catcher, Franks saw a great deal of action,. Owen signed on March 2 and Phelps returned on April 7 when the Dodgers were in Atlanta playing their way north. By now Franks was often playing with the “B” squad and although he was with the team when the season started, it was only to last for a couple of days. On April 17 he was optioned to the Montreal Royals in the International League.

The Dodgers were battling the Cardinals for the pennant in ’41. In early June, the lead changed seven times in nine games. As the Dodgers prepared to travel for important games with the Western clubs, they found themselves two games behind the Redbirds in the standings but without a backup catcher. Phelps was suffering from numerous ailments including exhaustion (he could not sleep for fear his heart would stop). He was not at the train station with the rest of the team and the train left without him. Durocher was furious and had had enough. The Dodgers suspended Phelps and recalled Franks from Montreal. “I repeat, I’m through with Phelps. I don’t want him on my club. Franks is here now, and he’s my kind of player,” Durocher was reported to have said.5 Franks made it to St. Louis by June 14 and started the second game of the series. He did not have the spectacular start to the season that he did the previous year but he provided valuable relief to the overused Owen. Franks started seven of the 13 games on the Western swing, contributing a key pinch-hit three-run home run on June 23 at Forbes Field. The Dodgers, 10-3 on the road trip, were 6-1 when Franks started. He stayed with the club for the remainder of the season getting into 57 games, 54 at catcher. He hit .201 (28-for-139) with seven doubles and a home run for the World Series-bound Dodgers.

By the start of the 1942 season, the country was at war and world events overtopped the significance of most things, not excepting baseball. Franks started the season with Montreal but by May 14 he was an ensign in the Navy. From Buffalo, New York, where he enlisted, he was sent to Annapolis, Maryland, for 30 days of instruction, ultimately becoming a physical instructor in the naval-aviation program. He spent the next four years getting Navy cadets into shape and playing (and managing) baseball in Florida, Virginia, and Hawaii; he was discharged on January 9, 1946.

Now 32, Franks spent the entire 1946 season with the Montreal Royals, a now-famous team that won 100 games, won the International League pennant and championship series, and was led on the field by Jackie Robinson. Franks had an excellent season, appearing in 100 games, catching 87 and hitting .280 with 14 homers and 16 doubles. He also walked a reported 72 times for an impressive on-base percentage of .424. In 1947 Franks moved to the St. Paul Saints in the Triple-A American Association, another Dodgers farm team, where he became the player-manager. He played in 49 games and guided St. Paul to a 52-74 record. In late August, though, his contract was sold to the Philadelphia Athletics and Franks was back in the big leagues. It was a fortuitous move for Franks; it allowed him to qualify for the major-league pension instituted the year before, and in Philadelphia, he met his future wife, Amneris Lorenzon. The two were married in 1948 and eventually had three children. Franks appeared in eight games for the A’s in ’47 and in 40 games in 1948.

Durocher, who had become the Giants manager in midseason in 1948, was assembling his own coaching staff for 1949 and he wanted Franks. Franks asked for and was given his release by the A’s. As a coach Franks would join Frankie Frisch and Freddie Fitzsimmons as coaches, with Franks working with the young pitchers. The New York Times said, “[Franks] is Durocher’s own choice, Leo having had Franks under his wing with the Dodgers.”6 It was the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship for Franks with Durocher and the Giants, not just in New York but in San Francisco as well.

Franks coached under Durocher in New York for seven seasons, a time that included two pennants (1951 and ’54) and a World Series championship when the Giants beat the highly favored Cleveland Indians (’54). The 1951 New York Giants are famous for mounting one of the most incredible comebacks in professional baseball history. After losing to Robin Roberts and the Phillies on August 11, the Giants, 13 games behind first-place Brooklyn, won 37 of the next 44 games to tie the Dodgers on the last day of the season. They then beat the Dodgers, in the best-of-three playoff, punctuated by the most famous home run in baseball history, Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard Round the World.”

In The Echoing Green, investigative journalist Joshua Prager, building on the work of others and conducting his own exhaustive research, including interviewing Franks, convincingly demonstrates that the Giants cheated and that Herman Franks was at the center of the cheating. The cheating Prager portrays is sign-stealing, a much-honored skill if it is done on the field without mechanical or electronic aids. Durocher, though, placed Franks in the Giants’ clubhouse office in the Polo Grounds, beyond center field, some 500 feet from home plate. Armed with a telescope and thousands of hours of baseball experience, Franks would peer in on an opponent catcher’s signs and then, through a buzzer system Durocher had installed, he would signal bullpen catcher Sal Yvars who would signal the batter. Franks was there when Thomson came to the plate in the bottom of the ninth on October 3, 1951, although Thomson later told Prager he was concentrating so hard he never looked at Yvars. Franks never admitted anything. He told the Associated Press in 2001, “I haven’t talked about it in 49 years. If I’m ever asked about it, I’m denying everything.”7

Durocher was out after the 1955 season (guys who aren’t that nice finished third) and Bill Rigney was in. Rigney, naturally, wanted his own coaches; consequently Franks was not retained. He did some scouting for the Giants, covering the Western United States, for the next two years, but Franks had real-estate and other business interests in Salt Lake City. He was garnering a well-deserved reputation as an astute businessman. He was becoming wealthy as well. Franks downplayed it but newspaper articles often mentioned that he was likely a millionaire.

Franks did not need the job; however, when the Giants established a new home, in San Francisco for the 1958 season, he was coaching third base under Rigney. The position lasted just one season, though. He left the Giants to become the general manager and owner of the Salt Lake City Bees in the revamped Pacific Coast League. In 1961 he was the manager for part of the season, taking over from former teammate Freddie Fitzsimmons. The major leagues came calling again in 1964. Giants manager Alvin Dark hired Franks again to coach third. The Giants, with Mays, McCovey, Marichal, and Cepeda, finished a disappointing fourth. Just hours after the season ended, Giants owner Horace Stoneham fired Dark and replaced him with Franks, inking him to a one-year contract at a reported $35,000.8 At what was characterized as a “hastily organized news conference,” the new manager was confident, stating, “[t]his club definitely has possibilities to win the pennant. If I didn’t think they could win it, I wouldn’t have taken the job. … We gotta win and we have to keep this group together and playing as a team.”9

Franks was at the Giants’ helm for the next four seasons, 1965-1968, winning 367 games (91.75 games/season), more than any other major-league club during that span. He managed MVP seasons by Willie Mays, multiple 25-plus-win seasons by Juan Marichal, and great seasons by Willie McCovey, Gaylord Perry, and others. He did everything but win the pennant, finishing second in four consecutive seasons. Before the 1968 season Franks had told Stoneham that if he didn’t win the pennant, he was quitting. The ’68 Cardinals won 97 games, 9 more than the Franks-led Giants. True to his word, Franks resigned. Years later Joey Amalfitano, friend and confidant, saidthat Franks regretted telling Stoneham he would win it all or else. “He still had his juices flowing,” Amalfitano said.10

Franks returned to his business interests which now included being Willie Mays’ financial adviser. In mid-August of 1970, Franks was in Chicago meeting Mays, who was in town with the Giants. Cubs pitching coach Joe Becker suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized. Old friend and now Chicago manager Leo Durocher asked Franks to serve as his pitching coach for the remainder of the season and Franks agreed. The coaching gig did end with the season, though, and Franks was out of baseball for the next six years. In November 1976, when Bob Kennedy, who managed the Franks-owned Bees in the early 1960s, became the vice president of baseball operations for the Chicago Cubs, he fired Jim Marshall and hired Herman Franks. Franks, whom Kennedy characterized as having “a lot of money” and “not looking for work,” became, at 63, the oldest manager in the major leagues. He indicated it would be “no problem for him.” Further, he added, “[a]ll managers are in the same boat regardless of age. My goal for the Cubs is simple — win games and win a pennant before I retire.”11 The choice of Franks was met with some bemusement, especially by the Chicago press. “[T]he 63-year-old, tobacco-spewing, story-teller … needs to manage a baseball team about as much as he needs another apartment building.” Franks, it was thought, must be bored; he was not hungry; he was not married to baseball.12

The Cubs won six more games under Franks in 1977 than they had in 1976, getting to .500 but still finishing 20 games behind the Phillies. The ’78 Cubs managed only 79 wins and when the ’79 Cubs, falling out of contention after the All-Star break, were shut out by the Pirates on September 23, Fan Appreciation Day, Franks resigned. Quitting during the season rarely goes well, but Franks’ resignation was particularly ignominious. He apparently told a reporter he was fed up, said some of his players were crazy, and showed the reporter a check he had written for $24,000 to join a Salt Lake City Country Club for 1980. “You don’t think for a moment that I would shell out $24,000 and then come back here and manage. Next year, I’ll be at the country club every day, that’s where I’ll be.” After it was reported, Franks tried to take it all back, then he resigned the same day. It was an unfortunate way to end his baseball career. Franks said age didn’t matter, but the age difference did. He was brought up in baseball in a different era and could not relate to the players of the nascent free-agent era. Many of them could not relate to him either. Overall, Franks managed 1,128 games, winning 84 more than he lost.

Amazingly, given the way Franks left, Cubs owner William Wrigley hired Franks as his interim general manager after Bob Kennedy, embarrassed by a 6-27 start, resigned in May 1981. Franks took the job “under certain conditions. I want complete control of the club, the players, and their agents,” he told the press.13 He held the job for the remainder of the lockout-shortened season and apparently wanted to shed the interim label and take the job for 1982, but it was not to be. The Cubs finished 38-65 and went with Dallas Green as the new GM. Franks was offered a job in the broadcasting booth and as head of the marketing department. He declined both. Jerome Holtzman, writing then for the Chicago Tribune, felt Franks didn’t get the credit he deserved, either as a field manager (“[n]obody ran a game better”) or as an administrator, “[Franks] has such a trigger mind that he expects others, who are slower, to react as quickly and decisively as he does. He should have been an owner, not an employee.”14

Herman Franks enjoyed a long life, living another 27 years after he left the Cubs. He continued his successful business career and, in addition to advising Mays, he worked as a financial adviser to Willie McCovey, Ernie Banks, and others. While he never worked in professional baseball again, he was active in player alumni groups and was active on the speaking circuit. He was elected to the Utah Sports Hall of Fame in 1974 and there is a sports complex in Salt Lake City named for him.

On March 30, 2009, at age 95, Herman Franks succumbed to congestive organ failure. He was survived by his wife of 61 years, Amneris, and their three children, Daniel, Herman Jr., and Cyndi. Shortly before he died, Franks gave a cogent summation of his career to a Salt Lake Tribune reporter, “I was a good receiver. I had a good arm. I wasn’t a good hitter. I was good at handling pitchers. But I loved the game, and I always wanted to stay in it as a coach or manager.”15

Last revised: September 10, 2023 (zp)

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com.

Prager, Joshua, The Echoing Green: The Untold Story of Bobby Thomson, Ralph Branca and the Shot Heard Round the World (New York: Vintage Books, 2008).

Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Stars Capture Easy Contest,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 1932, A11.

2 “Rickey Talks Coast Back to Former Waiver Rule,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1938, 1.

3 “Herman Franks Sworn In as Navy Ensign,” Washington Post, May 15, 1942, 31.

4 “Dodgers Buy a Catcher,” New York Times, February 5, 1940, 24.

5 Robert W. Creamer, Baseball in ‘41 (New York: Viking, 1991), 180.

6 “Giants Win Race for Rookie Hurler,” New York Times, November 16, 1948, 41.

7 Richard Goldstein, “Baseball’s Herman Franks Dies at 95,” New York Times, March 31, 2009.

8 “Giants Drop Dark as Manager, Appoint Franks His Successor,” New York Times, October 5, 1964, 45.

9 “Giants Fire Dark; Franks Manager,” Boston Globe, October 5, 1964, 19.

10 John Shea, “Led Giants to Four 2nd-Place Finishes,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 31, 2009.

11 Bob Logan, “Kennedy Named VP: Franks New Cub Manager,” Chicago Tribune, November 25, 1976, E1.

12 Rick Talley, “Franks Could Be Just Rich ‘Guest,’ ” Chicago Tribune, November 25, 1976, E3.

13 “The Cubs Bring Back Franks as GM,” Washington Post, May 23, 1981, D2.

14 Jerome Holtzman, “Franks Might Stay With Cubs — If Asked,” Chicago Tribune, October 27, 1981, D3.

15 Jay Drew, “SLC Baseball Legend Herman Franks Dies at 95,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 31, 2009.

Full Name

Herman Louis Franks

Born

January 4, 1914 at Price, UT (USA)

Died

March 30, 2009 at Salt Lake City, UT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.