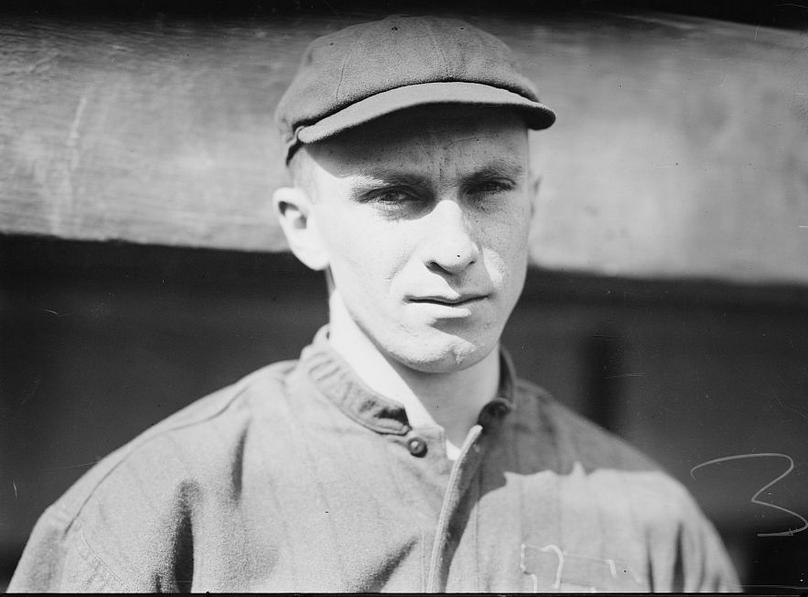

Iron Davis

Scholar-athlete George “Iron” Davis was the secret weapon of the Miracle Braves’ pitching staff. Manager George Stallings had used the 24-year-old right-hander just three times during the first five months of the 1914 season, but when he turned Davis loose, the Harvard Law School student responded with his career highlight: a no-hitter, on September 9, 1914. During a barrage of doubleheaders down the stretch, he and other members of the supporting cast gave respite to the hard-pressed frontline starters. The Big Three of Dick Rudolph, Bill James, and Lefty Tyler proceeded to pitch brilliantly in the World Series sweep of the Philadelphia Athletics.

Scholar-athlete George “Iron” Davis was the secret weapon of the Miracle Braves’ pitching staff. Manager George Stallings had used the 24-year-old right-hander just three times during the first five months of the 1914 season, but when he turned Davis loose, the Harvard Law School student responded with his career highlight: a no-hitter, on September 9, 1914. During a barrage of doubleheaders down the stretch, he and other members of the supporting cast gave respite to the hard-pressed frontline starters. The Big Three of Dick Rudolph, Bill James, and Lefty Tyler proceeded to pitch brilliantly in the World Series sweep of the Philadelphia Athletics.

Before going to law school, Davis starred at Williams College, in Wiliamstown, Massachusetts. Amid his studies, he spent parts of four seasons in the majors from 1912 to 1915. His pro baseball career ended in 1916, and George returned to his hometown, the Buffalo suburb of Lancaster, New York. There, for more than four decades, he pursued a career in the law and enjoyed assorted intellectual interests.

George Allen Davis Jr. was born on March 9, 1890. In many ways, his life echoed his father’s. George A. Davis, Sr. (1858-1920), born in Buffalo to British immigrants, was a lawyer with what the Albany Law Journal called “a large and lucrative practice,” and also was active in public life. Davis married Lillie Nina Grimes of Lancaster, and was Lancaster town supervisor from 1888 through 1897. He also was a New York state senator, and commander of the 74th Regiment of the New York National Guard.

The Davises had one other surviving child besides George, a daughter named Gladys (another boy apparently died young). Lillie, his mother, died on May 1, 1900, when George, Jr. was 10 years old.

In a 1914 feature article on George, Jr., the sportswriter Hugh Fullerton wrote, “Davis was not a strong youth. He was handicapped by physical unfitness.”1 This was perhaps one reason why he went to St. John’s Military Academy in Manlius, New York.

After graduating from St. John’s, George went to Williams College. Though he eventually became vice-president of his class, he got off to a rocky start academically. His classbook said, “How George occupied himself his freshman year is more or less a mystery, and the class almost lost him.” It turned out that the would-be athlete – who apparently had no experience in baseball before he came to Williams – had devoted himself to exercise.

Prefiguring the Charles Atlas ads, “Iron” transformed himself physically, as Ring Lardner wrote. “His strength was confined to his brains and he had the physique of an Oliver Twist. …. Almost unnoticed, he worked long hours in the gymnasium and worked so hard that in a year his pals could scarcely believe he was the same boy.”2

Hugh Fullerton wrote, “He never had played a game of baseball, and his knowledge was confined to theory. In the gymnasium he commenced working with a baseball, throwing at a padded surface and studying every ball he threw.” Fullerton continued, “The coach discovered that there was a pitcher working in the gym who knew more about pitching than any of the regulars did, and Davis was allowed to join the squad and pitch. There were many things he did not know, but his theories worked out and he became a great college pitcher.”3 The coach was Billy Lauder, who oversaw the Williams nine from 1907 through 1910.

After emerging as a star – and lifting his classroom performance to Phi Beta Kappa level – George became team captain for the 1912 season. His accomplishments led major-league teams to take an interest in him. Even before Williams ended its season, Davis began to receive some offers, but deflected them so he could finish out the college campaign.

On June 27, the day after the school year finished, Davis signed with the New York Highlanders, as they were still known (it was their last season under that name before they became the Yankees). His salary was reported to be $5,000 – then the biggest ever for a pitcher coming out of college.4 “Possessing great speed, curves, and control. . .he has been a sensation in the college baseball world and has helped Williams to defeat practically all of her rivals. He is considered the leading college pitcher, either east or west.” 5

Davis made his debut at Hilltop Park in the second game of a doubleheader on July 16. He pitched well but lost 3-1 to the St. Louis Browns. Two runs scored in the third inning because of Ed Sweeney’s error at the plate. George’s first victory came on August 27, as New York beat Cleveland 6-4.6 It was his only win against four losses in 10 games that season. After a rough outing against Philadelphia on September 5, he was sent down to the Jersey City Skeeters. That December, the New York Sun sniped, “George Davis is the strongest man in Williams College. . . .but we regret that he didn’t put all that stuff on the ball when pitching for the Highlanders last summer.”7

Several college publications show Davis as a member of the Williams Class of 1913. While other sources say that he graduated in 1912, a 1915 feature in Baseball magazine said, “He finished all his required work in the mid-winter semester [of 1913] so he was able to take the early training trip with the Yankees to Bermuda.”8 This included some workouts at Hamilton Cricket Field.9

He did not make the big club, though; he was sent to Jersey City once again. Manager Frank Chance “did not like Davis because he quit the training camp to get married.”10 Another article added that “Chance did not like the young man’s spirit and said he did not take base ball seriously enough.”11

Davis’s wife was Georgiana Jones. A granddaughter, Suzy Kissee, said, “Georgiana (called ‘Kiddo’ by everyone) was a practical joker and a suffragette. She was the first in her circle to raise her skirts above the ankle, and to be seen in public smoking, drinking, and driving a car. She was a voice for women’s rights early in the century. Since her marriage was considered ‘high profile’ for the day, this took a lot of courage. He enjoyed it all.”12 George and Kiddo had four children: a son, George A. Davis, III, and three daughters, Delancy, Eunice, and Deborah.

After returning from his honeymoon, George went to the minors, although he wasn’t happy about it — he reportedly said that he had enough money not to need the sport. He went 10-16 for Jersey City, striking out 199 men in 208 innings, according to the 1914 Reach Guide. He was also quite wild, however, and the Yankees sent him to another International League team, the Rochester Hustlers, who had a working relationship with the Boston Braves.

On August 25, the Braves purchased Davis from Rochester before he even pitched once there. George Stallings, as an opposing manager with Buffalo in 1912, knew of the young pitcher and liked what he had seen. The new recruit appeared twice in relief for Boston, allowing four earned runs over eight innings without a decision.

Meanwhile, Davis had decided to enter Harvard Law School, and in 1914 he pitched with the Harvard Law team before joining the Braves. He did not get into a game for Boston until July 1, when he started and lost. Meanwhile, at the encouragement of Stallings, George had been developing a new weapon – the spitball. On August 19, the Pittsburgh Press reported, “Fred Mitchell, supervisor of pitchers, has had the chap in hand for about a month now and claims that at the present moment he is about the best spitball pitcher in the National League.”13

The Braves had a September 9 doubleheader against the Phillies at their occasional home that year, Fenway Park. After Boston lost 10-3 in the opener, Davis – who had appeared just twice more in relief since July 1 – started the second half of the twin bill. It turned out to be the only no-hitter pitched in the National League that year. Davis walked five batters, three of them in the fifth inning, but Davis struck out Ed Burns, one of his four K’s for the day. He then escaped the jam by getting pinch-hitter Gavvy Cravath to hit into a double play.14 He also survived two errors by Red Smith at third. George even added three hits of his own, as he was always quick to note.

There are some unusual facts about this feat. Davis had the second fewest career wins (seven) of any man with a no-hitter to his credit in the majors. Only Bobo Holloman, with three, had fewer. The no-hitter was also the first ever at Fenway Park, not to mention the only one there by an NL pitcher as of 2010.

Following another relief appearance two days after the no-hitter, Stallings gave Davis four more starts down the stretch. He had declared confidence in his second string and could afford to use them as the Braves pulled away from the Giants – but it was also a matter of necessity. The team played no fewer than eight doubleheaders from September 23 onward, including four straight days from the 23rd through the 26th. Davis pitched creditably, beating Pittsburgh on September 19 and New York on October 1. He lost to Cincinnati on September 23 and at Brooklyn on October 6, the last day of the regular season.

Shortly after the World Series, Davis was back for his second year at Harvard Law. In early 1915, he showed again where his “Iron” nickname came from by setting a university record in the intercollegiate strength test. In those days, college athletes competed in a series of push-ups, pull-ups, dips, and other exercises, doing as many as they could in half an hour. The goal was to measure speed and endurance as well as pure strength. On February 12, Davis surpassed football star Tack Hardwick’s mark of 1,381 points, notching 1,437.6. Then on February 24, he leapfrogged his own record with a score of 1,593.8. It was all done for the entertainment of a few friends, according to Ring Lardner.

Although Stallings had hoped to have Davis in spring training, he permitted the pitcher to remain in Cambridge.15 Returning to the Braves in June 1915, Davis started nine times in 15 appearances. Again he posted a 3-3 won-lost record, while his ERA was 3.80.

The same held true the next season, as Davis returned his contract unsigned in February 1916. It was “understood that he will be tendered a contract which will permit him finishing his course at the Harvard law school before resuming baseball activities.”16 In late August, the Braves sent George to the Providence Grays on loan. His two outings with the Grays were his only pro action all season. Boston recalled him and infielder Joe Mathes on September 7, but he did not get into a game.17

Davis signed with the Braves again in February 1917.18 However, “he received his law degree at the age of 27 and simultaneously announced his retirement from professional baseball.”19 He then went into the Army, like his father, attaining the rank of captain in the infantry. George, who had taken fencing at Williams, specialized in teaching bayonet fighting.

Once World War I ended, Davis returned to Lancaster and joined his father’s law firm. He later formed his own partnership. However, as Buffalo baseball historian Joseph Overfield wrote, “In the Davis scheme of things, the law always seemed to be of secondary importance. In 1929, with egregiously bad timing, he gave up law to join a brokerage firm.” The stock-market crash wiped out the bulk of the family’s wealth.20

Davis served as a councilman-at-large in Buffalo from 1927 to 1933. He ran for mayor of Buffalo in 1933, although he lost in the Republican primary. Having returned to the law, he specialized in real estate. Around this time the Davises’ daughter Deborah died as a tot of 3 years old. She came down with a severe strep throat.

In addition to his law degree, Davis did graduate study in philosophy and comparative religion at the University of Buffalo. This spurred a new passion: astronomy. He amassed a library of some 1,500 books on the subject. He founded the Buffalo Astronomical Society in 1930 and later became honorary curator of astronomy at the Buffalo Museum of Science, where he taught classes for 30 years. Davis was an authority on astronomical history and especially on star names, contributing several articles to Sky and Telescope magazine.21 Broad study of foreign languages aided him in this pursuit. “He fluently read and wrote Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and Arabic,” Suzy Kissee said, “and he read Sanskrit. He learned these languages to help him in his passion.” George picked up Arabic using two dictionaries and no tutor. He also owned volumes in Egyptian hieroglyphics, and his monographs showed familiarity with Chinese.

“Another fun fact about him,” Suzy Kissee added, “is that he translated books from Latin to English for the library at Harvard when he attended there to help support himself. There is an old news clipping somewhere in the scrapbook that claims he worked on translations in the dugout during games and had to be told when it was his turn!”22

George’s deep love of books was also visible in his work for libraries. In 1947, he became a trustee of the Erie County public library system. Seven years later he was instrumental in the merger of Buffalo’s public libraries with the county’s. He continued to serve on the board and strongly supported the development of the Central Library.

On May 10, 1952, Georgiana “Kiddo” Davis passed away suddenly. Suzy Kissee said, “I deeply believe that my grandfather never recovered from her death. I have a picture of them taken nine days before she died, in which they look like a couple of high school sweeties. She kept him laughing. She was known as a practical joker. My mom told the story of her melting down chocolate Ex-Lax and including it in cookies to serve to guests she thought were arrogant!”23 George did get married again, to Grace Ogilvie, who shared his interest in astronomy.

Davis retired from his law firm on New Year’s Day 1961. He was 70 years old. “In an interview with the Buffalo Courier-Express, he said he planned to concentrate on his magnum opus, a two-volume work on the origins and history of the constellations. ‘I’ll probably be working on it for the rest of my life,’ he told the interviewer.”24 That work would remain incomplete, however – George Davis passed away on June 4, 1961.25 His obituaries did not mention that he ended his own life by hanging himself.

Joseph Overfield offered insight into his friend’s highly complex personality. Davis was “an intensely proud man, almost to the point of arrogance . . . an impatient man who did not suffer fools lightly . . . [yet] he often exhibited great patience with young lawyers who came under his wing, and it is told he delighted in playing mentor to neighborhood youngsters.” Overfield said that George’s only substantial asset was his library, and guessed that “he could not face a future of impecunity.”26

Davis is buried in the family mausoleum at Lancaster Rural Cemetery, along with his parents, sister, wife Georgiana, and children Deborah and George, III.

One may speculate about what George Davis might have achieved in baseball had he placed the sport over academics. There were certainly many lofty predictions. It’s a moot point, though, because Davis himself said, “Reading is my favorite sport. . . . There is nothing, not even baseball, that I like quite as well.”27 Yet even though his time in the majors was brief, he left a small but lasting mark. His Hall of Fame teammate on the Miracle Braves, Johnny Evers, said it well. “He is a fine fellow, a man who has little to say on the club and is generally popular among the players. I was glad to see him get the great reputation which goes to the pitcher of a no-hit game.”28

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Suzan Davis Packer Kissee and Mary Tucci Damiani, granddaughters of George Davis, for their personal memories and for furnishing articles from their grandmother’s scrapbook. Thanks also to Alan Brownsten.

Sources

Joseph Overfield’s 1989 article for the SABR Baseball Research Journal provided some other facts on George Davis’ life and career at Williams, in baseball, and afterward.

Background on the Davis family, George A. Davis, Sr., and his wife Lillie:

Derby, George, and James Terry White. The National Cyclopedia of American Biography. New York: James T. White & Company, 1906: 496.

Hull, John M. “George A. Davis.” Albany Law Journal, January 7, 1899: 73.

Murlin, Edgar L. New York Red Book. Albany, New York: J.B. Lyon Company, 1910: 83.

Chester, Alden and E. Melvin Williams. Courts and Lawyers of New York: A History, 1609-1925, Volume 1. New York, NY: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1925:

Hills, Frederick Simon, editor. New York State Men: Biographic Studies and Character Portraits, Volume 1. Albany, New York: The Argus Company, 1910: 172.

Who’s Who in New York City and State, Volume 9. New York: W.F. Brainard, 1911: 247.

According to The Braves Encyclopedia, George Davis Sr. was also a judge, but neither his entry in the New York Red Book nor any other source confirms this. Confusion may have arisen either with his father-in-law or because Davis was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

http://www.findagrave.com

http://www.thedeadballera.com

Notes

1 Fullerton, Hugh S. “‘No-Hit’ Davis Is an Object Lesson to All Young Men and Boys.” Pittsburgh Press, October 12, 1914: 17.

2 Unidentified, undated clipping from George Davis scrapbook.

3 Fullerton, op. cit.

4 “Yanks’ New Pitcher.” The Day (New London, CT), June 27, 1912: 10.

5 “Highlanders Sign Star Collegian.” Pittsburgh Press, June 27, 1912: 20.

6 Lanigan, Ernest J. “Davis Failure in American League.” Pittsburgh Press, September 12, 1914: 9.

7 “May Be Strong — But Did Not Show It When Pitching for the Highlanders.” Sporting Life, December 21, 1912: 14.

8 “George Davis, the No-Hit Hero of the Braves.” Baseball Magazine, February 1915: 30.

9 “Hard Work for Yankees.” New York Times, March 7, 1913: 9.

10 “George Davis Makes Stallings Rejoice by Pitching No-Hit Game.”

11 “George A. Davis, Jr.” Sporting Life, September 19, 1914: 1. This article wrongly stated that George had played his college ball for archrival Amherst — prompting an objection from The Williams Record and an erratum in Sporting Life’s October 1 issue.

12 E-mail from Suzan Kissee to author, January 26, 2010.

13 “Manager Stallings Has Spitball Star.” Pittsburgh Press, August 19, 1914: 21.

14 “Davis’ No-Hit Twirling Keeps Braves in Lead.” The Day, September 10, 1914: 11.

15 “Davis to Report Late.” The Pittsburgh Press, January 31, 1915: 28.

16 “Diamond Dust.” The Day, February 22, 1916: 12.

17 “Braves’ Roster Increased.” Pittsburgh Press, September 7, 1916: 24.

18 “Sherwood Magee Refuses to Sign.” The Day, February 21, 1917: 11.

19 “G.A. Davis Jr. Dead; Attorney, Widely Known Astronomer.” Buffalo Evening News, June 5, 1961.

20 Overfield, op. cit.

21 “George A. Davis, Jr. Dies.” Sky and Telescope, July 1961: 9.

22 E-mail from Suzan Kissee to author, January 26, 2010.

23 E-mail from Suzan Kissee to author, January 26, 2010.

24 Overfield, op. cit.

25 “George A. Davis Jr. Dies.” New York Times, June 5, 1961: 31; “G.A. Davis Jr. Dead; Attorney, Widely Known Astronomer”

26 Overfield, op. cit.

27 “George Davis, the No-Hit Hero of the Braves”: 30.

28 Ibid.: 31.

Full Name

George Allen Davis

Born

March 9, 1890 at Lancaster, NY (USA)

Died

June 4, 1961 at Buffalo, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.