Jack Haskell

Being a member of the umpiring staff of the 1901 American League has earned Jack Haskell an entry in modern-day baseball reference works. But that one-season tour of duty represents only a short chapter in the life of an outsized character who embodied a species now vanished from the baseball landscape: the hometown minor league celebrity. For more than 20 years, Haskell was the dean of turn-of-the-century non-major league umpires, most notably while serving as umpire-in-chief for the Class A Western League. Simultaneously, he served as the circuit’s unofficial promoter, talent scout, and troubleshooter, all the while declining intermittent overtures to return to umpiring in the big leagues.

Being a member of the umpiring staff of the 1901 American League has earned Jack Haskell an entry in modern-day baseball reference works. But that one-season tour of duty represents only a short chapter in the life of an outsized character who embodied a species now vanished from the baseball landscape: the hometown minor league celebrity. For more than 20 years, Haskell was the dean of turn-of-the-century non-major league umpires, most notably while serving as umpire-in-chief for the Class A Western League. Simultaneously, he served as the circuit’s unofficial promoter, talent scout, and troubleshooter, all the while declining intermittent overtures to return to umpiring in the big leagues.

Haskell’s reluctance to resume major league service was rooted in attachment to the city of Omaha, where he was a favorite son, noted raconteur, and occasional newspaper columnist; profitably engaged in café, saloon, and roadhouse ventures; and involved in local politics. Only the early arrival of Prohibition in Nebraska could get him to relocate. But once re-situated in the wide-open Kansas City of the 1920s, Haskell continued to thrive. In short order, he became the proprietor of a fashionable city hotel and a reliable vassal of powerful but corrupt Democratic Party boss Thomas J. Pendergast. Sponsored by Pendergast, Haskell was elected to six consecutive terms in the Missouri state legislature and was the chairman of an important statehouse committee at the time of his death in January 1940. The ensuing paragraphs recall this once regionally prominent but now forgotten umpire-publican-politician.

John B. Haskell was born in Omaha on March 5, 1869, the oldest of three sons born to clerk-salesman Ira T. Haskell (1838-1880), a native of Rhode Island, and his New York-born wife Elizabeth (née Dixon, 1839-1925).1 When Jack was still a toddler, the family moved to his maternal grandfather’s farm in southern Illinois. The Haskells returned to Omaha, however, before the death of father Ira in 1880; Jack completed his schooling there.2 By 1885, he was in the local work force, employed as a wholesale drug clerk.3 By then, his mother was remarried to an Omaha grocer named Redman and in time, Jack would have four new half-siblings. As a teenager, John himself became a married man, taking Mina Boyd, the 16-year-old daughter of Irish immigrants, as his bride. Their union would last more than 50 years but yield no children.

Like other young men of his generation, Haskell spent much of his leisure time on city sandlots. An outfielder, his skills did not rise to professional grade, but he did play some semipro ball. In 1892, he attempted to land a berth in the unaffiliated Nebraska State League, but found no employment.4 Instead, he was afforded a league tryout as a 23-year-old novice umpire.5 Although Haskell later maintained that it takes years for an umpire to master his craft, Jack was evidently a quick learner. By early July, Sporting Life’s Grand Island correspondent was reporting that “Haskell is fast earning a reputation as the best umpire in the league.”6

Haskell’s Baseball-Reference listing credits him with playing an 1893 game for the St. Joseph (MO) Saints of the fledgling four-club Western Association. Whatever the accuracy of that listing,7 the historical record unmistakably documents that “John B. Haskell of Omaha was appointed a Western Association umpire” in early June.8 Unhappily for Jack and all concerned, the WA folded three weeks thereafter.

Haskell’s return to a reconstituted Western Association in 1894 exhibited features that became hallmarks of his umpiring career. Weeks before the campaign’s start, Haskell initiated the regimen of long walks and vigorous exercise needed to sweat off the excess flesh that he put on each winter.9 And the sharp division of opinion regarding his umpiring competence was early in evidence. The hometown Omaha newspapers, particularly the World-Herald, could be relied upon for praise of Haskell’s work,10 and he was generally well-regarded elsewhere in the territory.11 Western Association sportswriter James Nolan, for example, was effusive in his commendation of Haskell and fellow arbiter Ed Cline, calling their work “incomparably fine. Their knowledge of the rules, their strictness and ability to keep good order on the field, and their impartiality make them as great a pair of umpires as ever handled an indicator.”12

But Haskell would always have a handful of Midwestern critics. His reappointment was panned in St. Joseph, with the local Sporting Life correspondent branding Haskell “grossly incompetent and his habits are of the worst kind.”13 That was the first discovered reference, however veiled, to a career-long impediment: a fondness for alcohol. Also making its first appearance was a temperamental streak that impelled Haskell to resign his post when he deemed himself slighted — almost invariably followed by reconciliation and reinstatement to duty.14

Another turn in the Western Association gained Haskell more Midwestern newspaper plaudits,15 and by the close of the 1895 season he was being touted for promotion to the National League.16 But Haskell was obliged to remain in the WA again in 1896, where his return drew the now-expected praise from most circuit observers, as well as brickbats from St. Joseph.17 Late that season, however, it was widely reported that National League President Nick Young was now making serious overtures toward having Haskell on his umpiring staff for 1897.18

In the end and for the time being, Haskell remained in the minors. But the year 1897 nevertheless proved a fateful one for our subject in two life-changing ways: (1) he was hired as an umpire by President Ban Johnson for the Western (later American) League; and (2) he met rising Kansas City powerbroker Tom Pendergast. By this time, Haskell had already entered local Democratic Party politics, making himself useful behind the scenes. He would continue to do so for the remainder of his years in Omaha before becoming an officeholder in Kansas City.

Haskell’s Opening Day assignment brought home the perils facing the one-man umpire. In addition to the pressures of close decision-making and the abuse of unhappy players and fans, there was the constant danger of injury. A twisted knee suffered in the Kansas City opener was followed by a severe ankle sprain in Milwaukee, both of which necessitated time off to recuperate. In the meantime, amateurs or designated ballplayers assumed his duties, unsatisfactorily. Haskell then compounded the Western League’s shortage of qualified umpires by taking an unscheduled “vacation” in mid-July, a two-day bender that promptly earned him a fine and indefinite suspension from league boss Johnson.19 But less than a week later, Haskell was back on the job,20 and completed the season without further incident.

Despite the mid-season lapse,21 Haskell’s umpiring work drew rave reviews.22 And once again, it was thereafter reported that he was ticketed for the National League in the spring.23 But Haskell rebuffed the NL when its salary offer was not significantly higher than the Western League wage, and came without a large cash advance.24 A grateful Johnson thereafter appointed Haskell his circuit’s umpire-in-chief.25 This, in turn, prompted the always-fawning Omaha World-Herald to declare that “Jack is one of the best in the business and the Western League is to be congratulated that [Haskell] withstood the blandishments of the big fellows and remained with his first love.”26

Haskell soon had reason to regret his decision. With the Western League in financial distress by midseason, the circuit’s board of directors ordered Johnson to cut expenses. Among the economies imposed by the league boss was a 25 percent reduction in the salary of his chief umpire ($60 from Jack Haskell’s $240 monthly paycheck).27 But Haskell was not having it and promptly submitted his resignation. He then went home to Omaha and spent the remainder of the summer officiating local amateur and semipro games.28 Haskell returned to the circuit in time to umpire a handful of late-season WL games, but his long-range plans were complicated by a commercial venture: the opening of an Omaha café that began “doing Klondike business.”29 Additional business opportunities lay in Haskell’s future, and henceforward the need to remain close to the cash register often clashed with the traveling requirements of umpiring.

In the short run, the diamond prevailed. Haskell returned to the Western League in 1899 and — apart from an on-field encounter with pugnacious Detroit Tigers shortstop Kid Elberfeld that left the arbiter with a bloodied face30 — completed a relatively uneventful season of umpiring. But big changes were on the horizon for both the Western League and its men in blue. Over the winter, the circuit officially changed its name to the American League, signaling the intention to transform itself into something larger than a merely regional operation. The AL then placed franchises in past and present major league venues like Chicago, Cleveland, and Buffalo. For the time being, however, the American League remained a minor league circuit, thus avoiding direct conflict with the long-established National League.

The umpiring staff assembled by AL President Johnson included Jack Haskell.31 But before the 1900 season commenced, Haskell resigned his position to oversee another commercial venture — the roadhouse that he and a partner had opened outside Kansas City.32 He also retained his interest in the Omaha café.33 Haskell, therefore, did no professional umpiring that year. But he was back in harness for 1901, the momentous inaugural season of the American League as a major league circuit.34

The umpiring staff assembled by AL President Johnson included Jack Haskell.31 But before the 1900 season commenced, Haskell resigned his position to oversee another commercial venture — the roadhouse that he and a partner had opened outside Kansas City.32 He also retained his interest in the Omaha café.33 Haskell, therefore, did no professional umpiring that year. But he was back in harness for 1901, the momentous inaugural season of the American League as a major league circuit.34

The officiating arrangements devised by Johnson — four traveling umpires (including Haskell) to work the plate and eight resident umps to handle base duty — allowed for most American League games to have two umpires.35 This scheme was designed to foster the clean, fast-moving style of play desired by Johnson for the new league, and to attract fans put off by the brawling, dirty-tricks game of the National League. But it could not eliminate playing field disputes, and the physical confrontations that sometimes came with them — as Jack Haskell, in particular, would discover.

Throughout his minor league career, Haskell was recognized as a no-nonsense arbiter with little tolerance for disputes of his decisions. He established that this would be his approach in the American League as well, tossing Washington’s Bill Everitt for arguing a pitch call on Opening Day. The Everitt ejection was only the first of the AL-leading 18 player dismissals ordered by Haskell during 1901, with those sent to the dressing room including future Hall of Famers John McGraw, Nap Lajoie, and Jimmy Collins.36

Haskell’s authoritarian approach to decision making antagonized some players, including Baltimore first baseman Burt Hall, who punctuated his disagreement with a Haskell call at first by punching the umpire in the face in early August. Once report of the incident reached Ban Johnson, he immediately suspended Hall.37 Three weeks later in Washington, Chicago pitcher Jack Katoll, displeased by an inning-prolonging Haskell call that went the Senators’ way, retrieved a wild pitch and then fired the ball into Haskell’s unprotected right shin. Moments after Katoll was ejected, Sox shortstop Frank Shugart split Haskell’s upper lip with his fist, precipitating a near-riot by enraged Washington fans. Both Katoll and Shugart were arrested by DC police and taken to a local jail. The two were thereafter released on bail but indefinitely suspended by league president Johnson. Haskell, meanwhile, cleaned himself up and finished the game.38

After the Washington fracas, Haskell continued to work but soon the swelling in his right shin led him to be placed on leave to receive medical care.39 He returned to duty in time to complete the season, umpiring 121 American League games, total. Unbeknownst to all, Jack Haskell’s career as a major league umpire was now over. Still only 32 years old, he spent the next 13 years entirely in the minors, declining various invitations from President Johnson to return to AL umpiring ranks.

For the 1902 season, Haskell accepted a job with a newly-formed and independent minor league, the American Association.40 The Midwestern territory of the fledgling circuit kept Haskell in proximity to his business interests, and he completed the campaign uneventfully. Haskell returned to the AA the following year, and soon his work was drawing the customary praise. The Milwaukee Evening Standard declared, “Jack Haskell is without doubt the best umpire in the American Association, and in the entire minor league territory, for that matter.”41 But Haskell’s drinking soon placed him in hot water with AA brass.

When the umpire failed to appear for a two-game series in Columbus, Association president Thomas J. Hickey fined him $25. Claiming that he had been sick in bed, an indignant Haskell promptly resigned his position.42 In time and via the intercession of Milwaukee Brewers manager Joe Cantillon, a friend and former umpiring colleague of Haskell, and Milwaukee co-owner Charles Havenor, the conflict was patched up and Haskell returned in time to umpire the final weeks of the AA season. But Haskell’s time in the Association had reached its end.

When Haskell was released by incoming AA president J. Ed Grillo in January 1904, rival circuits competed for the umpire’s services. Responding to a complaint about Haskell’s drinking voiced in Columbus, a Saint Paul sportswriter responded, “Drunk or sober, Haskell stood head and shoulders above the other umpires hired by [former AA President] Hickey … and was the only umpire to command the respect of the players.”43 In late February, Haskell was signed to an Eastern League umpiring contract by circuit president Pat Powers.44 The following winter, Powers successfully fended off an American Association bid to recapture Haskell’s services and re-signed him for 1905. “Umpire Jack Haskell did splendid work for the Eastern League last season, and I would not think of letting him get away,” said Powers.45

Umpiring in the Northeast kept Haskell away from his business ventures, so at season’s end he sought work back in the Midwest. New American Association President Joseph O’Brien was happy to oblige, appointing Haskell AA umpire-in-chief for 1906.46 The signing was heartily welcomed by the Milwaukee Journal as “a piece of gladsome news to player and fan alike, as Jack is one of the most competent arbitrators that ever acted. He commands the respect of the men who play under him and that is what the public wants.”47 But the season proved an unhappy one for Haskell.

In early July, he resigned, with no explanation forthcoming from either the umpire or the league office.48 Days later, however, a Minneapolis Journal sportswriter somewhat cryptically reported that “Jack Haskell quit the AA over disagreement with President O’Brien on financial matters.”49 Whatever the cause, Haskell was soon engaged in an exotic new calling: advance man and barker for the Hagerbeck Traveling Circus. “It isn’t that much of a change at all,” said Jack. “I’ve met more wild animals on the ball field than Kipling ever thought of in his jungle stories, and it is merely a change of location every day instead of sojourning in the different towns for a series.”50

Circus life evidently lost its charm rather quickly, and by winter Haskell was back looking for work as an umpire. He soon landed a post that proved congenial: umpire-in-chief for the successor-version of the Western League.51 For the next half-dozen years, Haskell enjoyed the confidence of WL President Norris O’Neill; served as a talent scout for Chicago White Sox club boss Charles Comiskey,52 and basked in positive Midwest press — except for the Topeka (KS) State Journal and (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, relentless scolds of the umpire. Rushing, as always, to Haskell’s defense was the Omaha World-Herald, which proclaimed, “Haskell is one of the best umpires in the business. … He has less trouble and gets rid of what he does have with greater speed and facility than any umpire who can be named. He is a star performer.”53 And at $450 per month, Haskell’s stipend was near double what he had been paid by the Western League a decade earlier.54

In 1908, WL President O’Neill signed Haskell to a three-year contract and delegated selection of the circuit’s umpiring staff to him.55 Over time, Haskell assumed additional administrative work for the league, becoming O’Neill’s unofficial right-hand man. But midway through the following season, he was embarrassed when arrested in Denver and accused of being connected to a notorious ring of ballpark pickpockets, the leader of which was Jack’s longtime Omaha friend, convicted con man Rolla Noble. The incident was briefly exploited by Haskell nemeses like the Topeka State Journal and Rocky Mountain News.56 But the following day, the charges were dropped and the umpire more or less exonerated.57 Shortly thereafter, he was back behind the plate, and the matter was soon forgotten.

President O’Neill shifted more responsibilities onto Haskell’s shoulders in 1910. He now devised the game schedules for Western League umpires, increased to a grueling 168 games for that season and the next. He also promulgated a dress code for his crew — a matter that came naturally to a fashion plate partial to flashy suits, jaunty hats, and walking sticks, and often called the Beau Brummell of baseball.58 More important, he served as O’Neill’s emissary in Pueblo, assigned the task of preventing WL player defection to the Colorado State League.59 He also did promotional work for his circuit.60 But his work on the diamond continued to divide league observers, with Des Moines Boosters club president John F. Higgins joining the ranks of Haskell detractors.61 Still, the umpire retained widespread support; both American League President Ban Johnson and American Association boss Thomas M. Chivington recruited him for the 1911 season. Haskell turned down both men. In addition to being content as WL umpire-in-chief, Jack was now reportedly “pulling down as big a salary as is given to the best men” in major league baseball.62

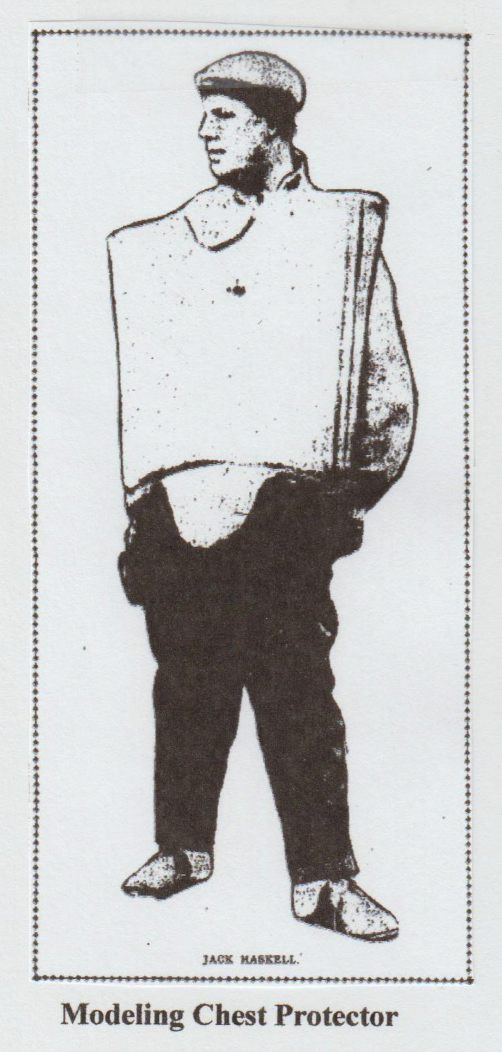

The 1911 season was preceded by Haskell’s annual spring labors to reduce the midriff flesh acquired over the winter and by invention of an inflatable chest protector for umpires.63 He was also empowered to impose fines upon any WL player assaulting an umpire. Regrettably for Jack, that power was unavailable to him after he was seriously injured by angry Pueblo fans after the home side dropped a 1-0 decision to Denver. Two of the umpire’s assailants were placed under arrest, but the fines later imposed had to be ordered by a Pueblo court, not by assault victim Haskell.64 Of more significance, Jack was dispatched to negotiate a possible Pittsburgh takeover of the financially failing Des Moines franchise after club owner Higgins abandoned the Western League.65

In February 1912, Haskell signed a new contract to continue as Western League umpire-in-chief.66 But far more press attention was devoted to a Haskell misadventure in a different sports realm the following month. While refereeing an Omaha boxing exhibition, Haskell was knocked cold by an errant overhand right thrown by Great White Hope heavyweight contender Fireman Jim Flynn.67 The baseball season also proved trying for Haskell, as the work of his umpires continued to receive fire, and discontent with chief umpire Haskell himself grew. At the fall league meeting, club owners directed President O’Neill to fire the entire WL umpiring crew, including Haskell. But Haskell replied that his contract with the league ran through the 1915 season and that he, for one, intended to remain on the job68 — despite a standing offer to join the American Association and other minor leagues.69 In the meantime, Jack and a business partner named Harry Pullman opened the Umpire Buffet, a new watering hole placed inside the Carleton Hotel in downtown Omaha.70 A natural raconteur, Haskell also amused himself by authoring often-improbable tales for the Omaha World-Herald.71

The umpiring situation reached crisis proportions in early 1913. First, WL President O’Neill announced that Haskell would return as chief umpire for the new season.72 But led by Sioux City Packers club owner Ed Hanlon and armed with the minutes of the fall meeting, Western League magnates refused to accede to Haskell’s retention, some even declaring that they would not place their clubs on the field if Haskell was umpire.73 This stance compelled O’Neill to sideline his umpire-in-chief until such time, if ever, that WL club owners unanimously agreed to his reinstatement.74

As it turned out, things could not have worked out much better for Haskell. His new saloon was a success, with the co-owners turning a reported $100 per day profit.75 Meanwhile, umpiring performance in the Western League sank to new depths, with the work of Haskell replacement George Sigler being deemed particularly objectionable. In mid-July, Sigler was terminated and Jack Haskell recalled to duty.76 But for reasons never made public, he did not finish the WL season and was placed on the suspended list over the winter.77

Notwithstanding his Western League suspension, demand was high for Haskell’s services that winter. Old boss Ban Johnson wanted him to return to the American League.78 The National League also made a bid for him,79 while the American Association renewed its standing offer for the veteran umpire to join their circuit.80 But his most ardent suitor was a new arrival on the baseball scene, the self-declared major Federal League. Its agents offered him a $1,000 signing bonus in return for his signature on an FL umpiring contract.81 But whether a matter of convenience, loyalty to Norris O’Neill, or something else, he re-upped with the Western League, accepting a modest $400 per month stipend that he could have bettered by accepting one of his other employment offers.82

In the opinion of Omaha sportswriter (and Haskell friend) Sandy Griswold, the veteran ump “knows the rules better than their makers, has oodles of intuitive baseball sense, and as a strictly honest and thoroughly competent arbiter, cannot be beaten.”83 These attributes, however, did not shield Haskell from on-field mishap. In mid-June, a foul-tip foot injury resulted in blood poisoning that confined him to bed for a week.84 Shortly after he returned to action, he dislocated a toe and tore tendons in his foot while racing to cover a play at first base during a 7-2 Denver victory over Des Moines on July 19, 1914.85 Unbeknownst to all concerned at the time, the date marked the end of Jack Haskell’s career as a professional umpire. Sometime thereafter and for reasons never publicly disclosed, the still-disabled Haskell was laid off by President O’Neill without warning or explanation, but with his salary for the remainder of the season paid in full.86 He was then placed on the Western League’s suspended list.87

Over the winter, the Federal League renewed its contract offer to Haskell.88 And the Western League’s official release of the umpire removed him from Organized Baseball’s ineligible list.89 But Haskell’s baseball days were now behind him. His new objectives included an “earnest desire … to set a new record in the matter of spirit consumption,”90 and expansion of his business interests by becoming the public face of an unlicensed roadhouse opened just outside Omaha city limits in Riverside — a venture that soon visited much grief upon Haskell. His partners in the new venture included Omaha Democratic Party fixer Tom Dennison and county commissioner John Lynch, entrusted with ensuring its political protection. The roadhouse made up the income that Haskell lost when local prohibitionist forces succeeded in banning the sale of spirits in city establishments, including the Umpire Buffet, and allowed him to decline offers to return to umpiring reportedly extended to him by the American League in 1916 and by both major leagues and the American Association the following year.91

In May 1917, a newly elected county attorney publicly accused the proprietors of the Riverside roadhouse of various regulatory and criminal infractions including unlicensed operation, illegal gambling, after-hours sale of alcohol, and corruption of a government official — county commissioner Lynch, the primary target of the county attorney’s investigation.92 After legal skirmishing, Haskell, Dennison, and company were compelled to testify that Lynch was paid $600 a month to ensure that Riverside operations went unmolested by officialdom. The county attorney then filed criminal complaints against all concerned, including Haskell.93 But witnesses disappeared and other proof problems proved insurmountable, and the criminal case was eventually abandoned by the county attorney in April 1918.94

In May 1917, a newly elected county attorney publicly accused the proprietors of the Riverside roadhouse of various regulatory and criminal infractions including unlicensed operation, illegal gambling, after-hours sale of alcohol, and corruption of a government official — county commissioner Lynch, the primary target of the county attorney’s investigation.92 After legal skirmishing, Haskell, Dennison, and company were compelled to testify that Lynch was paid $600 a month to ensure that Riverside operations went unmolested by officialdom. The county attorney then filed criminal complaints against all concerned, including Haskell.93 But witnesses disappeared and other proof problems proved insurmountable, and the criminal case was eventually abandoned by the county attorney in April 1918.94

By the time of the dismissal of the criminal charges against him, Haskell had relocated. The adoption of statewide prohibition laws by Nebraska in December 1916 had forced the shuttering of his Omaha businesses, and he sought a new start in licentious Kansas City. With the assistance of Missouri political boss Tom Pendergast — a longtime acquaintance whom he had become closer to while business partners with Harry Pullman and Tom Dennison, both friends and political allies of Pendergast — Haskell soon found himself proprietor of the downtown Majestic Hotel. The premises closed during the ensuing Great Depression, but once Prohibition ended, Haskell returned to the saloon trade, operating a Kansas City hangout called The Assembly. The moniker was apt, for by that time he was ensconced in the Missouri state legislature as Democratic Party representative for the First District of Jackson County (Kansas City), elected to six consecutive terms beginning in November 1926. The 1932 FDR Democratic Party landslide then gave the Pendergast forces control of the Missouri state legislature, with reliable Jack Haskell assuming the chairmanship of the important House Committee on Accounts.95

Although a renowned barroom orator and newspaper story teller, Haskell was a close-mouthed and largely inert legislator. “You know, I quit umpiring to get into politics,” he once explained. “But it wasn’t because I had any pet bills. I decided that I wouldn’t propose any new laws unless I believed they were badly needed and no one else suggested them. A man can legislate just as well with silence, studying bills, and intelligent votes as he can with loud speeches.”96 Rather, Haskell understood that his primary job was to protect the interests of his patron. As he candidly admitted as his political career neared its close, he was “a Pendergast goat in Kansas City politics for 39 years.”97

As the 1930s came to a close, both Haskell and his wife were in failing health. Suffering from chronic nephritis (kidney disease), Representative John B. “Jack” Haskell died in his Kansas City hotel room on January 3, 1940. He was 70. Following funeral services conducted at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, he was interred at Calvary Cemetery, Kansas City. Survivors included widow Mina (who would be laid next to her husband that June), and younger brothers Harry and William.

Acknowledgments

A non-annotated version of this profile was published in the Fall 2020 issue of Beating the Bushes, the bi-annual newsletter of SABR’s Minor Leagues Research Committee. This version was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Bill Johnson.

Sources

The biographical information provided above comes from US Census and other government records and contemporaneously-published newspaper articles. Unless otherwise noted, stats and minor league data come from Baseball-Reference and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997).

Notes

1 Jack’s younger brothers were Harry (born 1871) and William (1877).

2 The extent of Jack Haskell’s education was not discovered, but he likely had the elementary school education accorded working-class children of the era. Whatever the case, the adult Haskell was shrewd, literate, and loquacious (if not eloquent), and usually displayed sound business judgment.

3 Per the 1885 Nebraska state census.

4 See “Nebraska Sporting Notes,” Omaha World-Herald, March 27, 1892: 9.

5 Per “Nebraska League Notes,” Sporting Life, May 21, 1892: 1.

6 “Grand Island Items,” Sporting Life, July 2, 1892: 11.

7 The writer uncovered no evidence that Haskell ever played for St. Joseph, and the B-R listing that has him playing for the Burlington (Iowa) Colts of the Western Association in 1896 is clearly erroneous. Haskell spent that season entirely as an umpire.

8 See “Western League,” Wichita (Kansas) Edge, June 3, 1893: 3.

9 Per “Base Ball Briefs,” Omaha World-Herald, April 15, 1894: 12.

10 See e.g., “Base Ball Booming,” Omaha World-Herald, March 10, 1894: 5. The rival Omaha paper tended to be more restrained in its praise of the young umpire. See “Rock Island Gets Even,” Omaha Bee, May 7, 1894: 3.

11 See e.g., Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, May 30, 1894: 6: “Jack Haskell, since the first day he came, has conducted himself in a gentlemanly manner and his decisions have bee generally fair and impartial.”

12 James Nolan, “A Model League,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1894: 1.

13 Carroll, “The Umpires,” Sporting Life, April 7, 1894: 6.

14 See “Miscellaneous Sports,” Omaha World-Herald, July 9, 1894: 2 (resignation); “Base Ball Briefs,” Omaha World-Herald, July 22, 1894: 12 (reinstatement).

15 See e.g., Lincoln (Nebraska) Capital City Courier, June 22, 1895: 10, and Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, August 8, 1895: 3.

16 See “Heard in the Bleachers,” Rockford Morning Star, September 12, 1895: 6. The rival Western League was also reportedly in pursuit of Haskell. See Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, December 10, 1895: 3.

17 Compare “Omaha on Dignity,” Sporting Life, February 15, 1896: 9, with “St. Joseph Jottings,” Sporting Life, February 1, 1896: 1.

18 See “Big League Wants Haskell,” Omaha Bee, August 3, 1896: 8; “The World of Sport,” Rockford Register-Gazette, September 14, 1896: 3.

19 As reported in “Suspended and Fined,” Indianapolis Journal, July 13, 1897: 4; “Infield Hits,” Minneapolis Journal, July 13, 1897: 10; “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, July 24, 1897: 5.

20 Per “Sporting Gossip,” Omaha World-Herald, July 18, 1897: 2; “Brief Ball Notes,” Rockford Register-Gazette, July 18, 1897: 3; “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, July 31, 1897: 5.

21 In era-typical code, our subject’s drinking problem was called “a weakness. … Haskell has promised to do better in this respect.” See “Johnson Umpires for 1898,” St. Paul Globe, January 30, 1898: 9.

22 See e.g., “Three Good Ones,” Sporting Life, November 6, 1897: 8.

23 See “Game on the Holiday,” Rockford Morning Star, November 23, 1897: 2; “Nick Young’s Staff,” Sporting Life, December 2, 1897: 6.

24 According to the St. Paul Globe, July 13, 1898: 6. Western League umpires Al Mannassau and Con Strothers also rejected NL offers.

25 Per “Among Sports,” Omaha World-Herald, March 6, 1898: 15; “Gossip for the Sports,” Rockford (Illinois) Republic, March 10, 1898: 5.

26 “Among Sports,” Omaha World-Herald, March 6, 1898: 15.

27 As reported in “The League Retrenches,” Minneapolis Journal, June 30, 1898: 10; “Cut in Salaries,” St. Paul Globe, July 1, 1898: 6; “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, July 9, 1898: 5.

28 Per “Baseball Notes,” Kansas City Journal, August 3, 1898: 6; “Baseball Pickups,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, August 21, 1898: 4.

29 According to “What Is Doing in Base Ball Way,” Rockford Morning Star, December 25, 1898: 8.

30 Elberfeld was immediately expelled from the Western League by President Johnson, but ended up ahead anyway, signed by the National League Cincinnati Reds before the 1899 season was out.

31 As reported in “Sports Miscellany,” Rockford Republic, March 17, 1900: 3; “The Next Meeting,” Sporting Life, March 17, 1900: 4.

32 See “Is This the Jack Norton?” Omaha Bee, February 6, 1900: 6; “In the American League,” Rockford Republic, April 21, 1900: 2; “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, June 16, 1900: 9.

33 Per “‘Adonis’ Terry To Replace Haskell,” Milwaukee Journal, April 16, 1900: 12; “News Notes from the Base Ball World,” Rockford Morning Star, April 22, 1900: 2.

34 Per “American League,” Indianapolis Journal, December 6, 1900: 9; “Brief Base Ball Notes,” Rockford Republic, March 22, 1901: 5; “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, March 23, 1901: 5.

35 See “The Umpire Question,” Sporting Life, March 30, 1901: 4.

36 For a complete rundown of the Haskell ejections, consult his Retrosheet entry.

37 As reported in “A Player Suspended,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, August 7, 1901: 6. See also, New York Sun, August 7, 1901: 6, and Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, August 7, 1901: 6.

38 As reported in “Two White Sox Arrested,” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1901: 4; “White Sox Arrested,” Washington Post, August 22, 1901: 8; and newspapers nationwide.

39 Per “Notes of the Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 31, 1901: 6; “Haskell Still in Bad Shape,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 1, 1908: 8. Adonis Terry filled in as traveling umpire in Haskell’s absence.

40 See “Haskell Will Umpire,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, March 7, 1902: 6; “Jack Haskell To Umpire,” Indianapolis Journal, March 7, 1902: 3; “Haskell Goes to New Association,” Cleveland Leader, March 8, 1902: 7.

41 As re-printed in “Off the Bat,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 22, 1903: 4.

42 Per “Umpire Haskell Resigns,” Duluth News-Tribune, July 17, 1903: 4; “Sporting Notes,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, July 17, 1903: 6; “Haskell Quits His Job,” Milwaukee Journal, July 17, 1903: 6.

43 Billy Mac, “Syndicate Ball Threatens AA,” St. Paul Globe, January 24, 1904: 15.

44 Per “Jack Haskell Is the Umpire,” Omaha World-Herald, February 24, 1904: 2; “Baseball Chat,” Rockford Republic, February 24, 1904: 2; “Out at First,” Boston Herald, February 26, 1904: 9.

45 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, January 21, 1905: 2.

46 As reported in “O’Brien Gets Umps,” Milwaukee Journal, February 17, 1906: 9; “Haskell Signs with Assn.,” Omaha Bee, February 21, 1906: 7; “Signs Umpire Jack Haskell,” Rockford Register-Gazette, February 21, 1906: 5.

47 “Jack Haskell Signs,” Milwaukee Journal, February 20, 1906: 11.

48 See “Umpire Haskell Out of O’Brien’s Staff,” Minneapolis Journal, July 2, 1906: 2; “Umpire Haskell Out a Mystery,” Chicago Daily News, July 3, 1906: 11.

49 “Boots and Boosts by the Dutch Uncle,” Minneapolis Journal, July 8, 1906: 32.

50 Ibid.

51 As reported in “Players Are Signing,” Rockford Register-Gazette, January 24, 1907: 5; “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, January 31, 1907, 23; “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, February 2, 1907: 3.

52 The most accomplished major league performer recommended by Haskell was Lincoln Tree Planters pitcher Eddie Cicotte. But Comiskey did not act upon Haskell’s recommendation in time, and Cicotte was acquired by the Boston Red Sox. Comiskey did not obtain his ill-starred staff ace until midway in the 1912 season.

53 “Keep ‘Em on the Hustle, Says Ump Jack Haskell,” Omaha World-Herald, July 22, 1907: 11.

54 Per “Small Sporting Palaver,” Omaha World-Herald, September 4, 1907: 6.

55 As reported in “The Chief of the Staff,” Omaha World-Herald, February 11, 1908: 4. See also, “Haskell To Be Chief Umpire of the Western League,” Denver Post, February 19, 1908:8 and “Sports Gossip,” Omaha Bee, March 5, 1908: 10.

56 See “Umpire Haskell One of Three Men Arrested, Charged with Robbing Crowds at Ball Park,” Rocky Mountain News, August 31, 1909: 1; “Met His Match,” Topeka State Journal, September 1, 1909: 1.

57 See “Jack Haskell Is Vindicated,” Denver Post, September 1, 1909: 1; “Umpire Jack Haskell Will Not Be Prosecuted,” Omaha World-Herald, September 3, 1909: 11. Haskell and the other arrestees strenuously protested their innocence and the charges were dropped after a stolen diamond stickpin was mysteriously returned to the theft victim.

58 See “World of Sport,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, March 12, 1910: 8; “Baseball Notes,” Winston-Salem (North Carolina) Journal, March 18, 1910: 2; “Umpires Must Keep Trousers Clean,” Duluth News-Tribune, April 3, 1910: 4.

59 As revealed in “Baseball Talk,” Topeka State Journal, January 26, 1910: 3.

60 Per “Umpires of the Western League,” Omaha Bee, March 13, 1910: 32.

61 As reflected in a Higgins missive to Des Moines newspapers re-published in the Topeka State Journal, May 3, 1910: 3.

62 According to “The Umpire Question,” Omaha World-Herald, December 24, 1910: 11.

63 Per Greenleaf, “Hot Off the Bat,” Omaha World-Herald, April 18, 1911: 7. Photos of Haskell modeling his new gear were subsequently published in the Rocky Mountain News, June 13, 1911: 18 and July 27, 1911: 9.

64 See “Two Fined for Assaulting Haskell,” Denver Post, September 11, 1911: 7; “News Notes,” Sporting Life, September 23, 1911: 21.

65 As reported in “Fred Clarke To Buy Des Moines,” Omaha World-Herald, August 22, 1911: 1.

66 Per “News Notes,” Sporting Life, March 2, 1912: 10.

67 See e.g., “Pugs and Umps Play, and Ump Goes Out,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 13, 1912: 7; “Ump Feels Weight of Fireman’s Fist,” Omaha World-Herald, March 15, 1912: 12; “Knocks Haskell Out,” Topeka State Journal, March 15, 1912: 8. The incident did not undermine the longstanding Haskell-Flynn friendship and that July, Jack led a large contingent of Flynn supporters to Las Vegas to witness the Fireman’s futile attempt to unseat heavyweight champ Jack Johnson.

68 As subsequently reported in “Western League in Turmoil Over Umpire Question,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 24, 1913: 10.

69 Or so he claimed in “Haskell To Train with Sox,” Omaha Bee, January 5, 1913: 40.

70 As reported in “Six Clubs on Trip,” Topeka State Journal, February 21, 1913: 4, and reflected in advertisement for the grand opening of the establishment published in the Omaha World-Herald, February 2, 1913: 26.

71 See Jack Haskell, “Lies I Have Told,” Omaha World-Herald, January 14 and 21, April 21, May 26, September 1, and October 27, 1912, and January 5, 1913.

72 Per “Hasn’t Offered Flynn Position as Umpire,” Omaha World-Herald, January 31, 1913: 4, and “Greatest Baseball Train Passes Through,” Omaha World-Herald, February 22, 1913: 8.

73 As reported in the Rocky Mountain News, March 23, 1913: 14; Salt Lake Telegram, March 24, 1913: 10, and elsewhere.

74 As gleefully reported by an implacable Haskell adversary. See Topeka State Journal, June 18, 1913: 4.

75 According to the Omaha World-Herald, September 3, 1913: 8.

76 As glumly noted in the Topeka State Journal, July 13, 1913: 4.

77 See “Minors’ Reserve List,” Sporting Life, October 18, 1913: 16. Whether Haskell quit to devote more time to his Omaha saloon or whether O’Neill suspended him for suspected dalliance with rival leagues is unclear.

78 As previously reported in the Omaha World-Herald, August 13, 1913: 8, and Topeka State Journal, August 18, 1913: 4.

79 Per the Rocky Mountain News, December 21, 1913: 56.

80 See “The World of Sport,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 13, 1913: 16.

81 Per longtime Haskell intimate Sandy Griswold in “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, December 16, 1913: 3.

82 As reported in “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, March 16, 1914: 9; “Jack Haskell Signs as Western L. Ump,” Denver Post, March 20, 1914: 16.

83 “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, March 16, 1914: 9.

84 See “Jack Haskell Able To Resume Job as Umpire,” Omaha World-Herald, June 27, 1914: 17.

85 As reported in “Umpire Haskell Dislocates Toe,” Rocky Mountain News, July 20, 1914: 7.

86 As later revealed in “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, December 8, 1914: 8. The guess, however, was that Haskell was disciplined for planning to jump to the Federal League. See “Baseball Notes,” (Little Rock) Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1914: 8.

87 See “Minors’ Reserve List,” Sporting Life, October 24, 1914: 17.

88 Per “Haskell Receives Offer from Federal League,” Omaha Bee, December 8, 1914: 9; “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, December 8, 1914: 8. Haskell was recruited for the Federal League by umpire-in-chief Bill Brennan, a onetime Western League colleague.

89 As reported in the Denver Post, March 19, 1915: 6.

90 Per “One Minute Interviews with Omahans Who Swore Off, or On, Something,” Omaha World-Herald, January 10, 1915: 5.

91 For 1916, see “Sandy’s Dope, Omaha World-Herald, March 23, 1916: 11. For 1917, “Sandy’s Dope,” Omaha World-Herald, February 17, 1917: 7.

92 Per “Move To Oust Johnny Lynch Started Here,” Omaha Bee, May 27, 1917: 3.

93 As reported in “Lynch, Dennison and Nesselhous Arrested on Criminal Charge,” Omaha Bee, February 26, 1918: 1; “Magney Says These Men Sold Liquor and Had Gambling House at Riverside,” Omaha World-Herald, February 26, 1918: 3.

94 See “Roadhouse Cases Are Dismissed in Court,” Omaha World-Herald, April 27, 1918: 2.

95 More prominent members of the Pendergast political machine included Missouri Governor Lloyd C. Stark and US Senator (and future President) Harry S. Truman.

96 “Hard-Boiled Ump Becomes ‘Silent Jack’ Haskell, Doubting Loud Roars Are Virtue in Legislature,” Jefferson City (Missouri) Post-Tribune, March 10, 1935: 14.

97 Jefferson City Post-Tribune, January 20, 1938: 6, citing a quotation by Representative John B. Haskell for the annual Missouri Blue Book, a collection of state house profiles.

Full Name

John B. Haskell

Born

March 5, 1869 at Omaha, NE (US)

Died

January 3, 1940 at Kansas City, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.