Adonis Terry

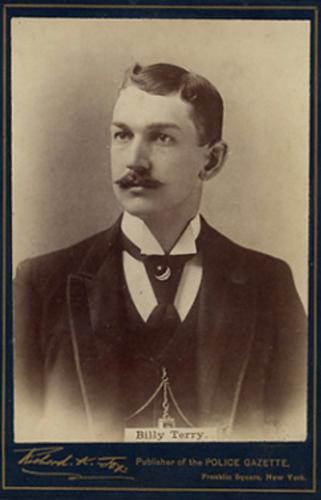

Adonis Terry debuted in the first major- league game played by the franchise that became the Dodgers and saw the start of his last game delayed by an electrical fire in a doomed grandstand. During the 13 years in between, the tall, mustachioed right-hander threw two no-hitters, earned two pennant-clinching victories, won three World Series games, and became the only NL (or AL) 20-game winner to steal 30 bases in a season.

Adonis Terry debuted in the first major- league game played by the franchise that became the Dodgers and saw the start of his last game delayed by an electrical fire in a doomed grandstand. During the 13 years in between, the tall, mustachioed right-hander threw two no-hitters, earned two pennant-clinching victories, won three World Series games, and became the only NL (or AL) 20-game winner to steal 30 bases in a season.

Over the course of Terry’s career, 1884-1897, pitching changed dramatically: from using below-the-shoulder motions to deliver balls where batters wanted them (high or low), to openly deceiving batters using unconstrained windups. At one time the reputed speediest pitcher of them all,1 Terry relied on a high kicking motion, with a repertoire that included “the sharpest and speediest [outcurve] ever seen” and an infrequently used slow ball one writer called “simply wonderful.”2 Terry’s heavy use of breaking pitches did, however, leave him with arm problems throughout his career.3

Playing for the Brooklyn Atlantics/Grays/Bridegrooms/Grooms, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Chicago Colts, Terry was 197-196, with a 3.74 ERA. He battled control issues throughout his career, finishing fourth in HBP, fifth in walks, and 10th in wild pitches among 19th-century pitchers. A two-way player early in his career, Terry spent 216 games patrolling the outfield, 16 at shortstop, and an equal number elsewhere. In 2003, sabermetrician Bill James rated Terry the 11th greatest hitter/pitcher all-time, based on Win Shares: ahead of Hall of Famers Walter Johnson, Old Hoss Radbourn, and Red Ruffing.4

Dubbed “Adonis” for his heavenly appearance, Terry’s good looks, gentlemanly manner, and aversion to alcohol gave him a charisma that appealed to many in an era when rough and bawdy ballplayers were commonplace. That appeal accentuated his successes on the diamond, making him a hero in Brooklyn and popular wherever he played. As the New York Herald put it after one triumph, “Terry captivated the hearts of the girls and made the other handsome men present envious.”5 Henry Chadwick, the Father of Baseball, called him “a man of strictly temperate habits, an intelligent worker, a faithful man in service and a credit to the fraternity.”6

William Henry Terry was born on August 7, 1864, in Westfield, Massachusetts. He was the first child born to Hiram and Mary Terry, who’d married on the day in July 1863 that Hiram was drafted into the Union Army.7 Hiram likely mustered out soon after, because his name doesn’t appear in any Massachusetts military unit’s Civil War roster. A farmer before the War, by 1865 Hiram was a ship carpenter, living with his family in Fall River. The 1870 census shows the Terrys living in nearby Dartmouth.

Terry pitched for the Racquet Club of Ludlow, Massachusetts, in 1879, but nothing is known of his performance that year or the next. By 1881, he was living with an uncle in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and working in a nearby factory.8 That year and the next Terry pitched for the “plucky and enterprising” semipro Rosedales of Bridgeport.9 Notably, he tossed an October 1882 no-hitter in which he defeated Bridgeport native Tricky Nichols.10

Terry’s play drew the attention of another local: Jim O’Rourke, player/manager for the NL Buffalo Bisons. A contemporary story said that Brooklyn manager George Taylor secured Terry during a “quiet trip” to New England.12

Terry was an instant success with Brooklyn. The 18-year-old won his June 1883 debut against a college nine at Brooklyn’s Washington Park.13 The next day, he collected two hits while playing left field in a league contest with the Merritts of Camden (New Jersey).14

After the Merritts folded a month later, Terry teamed with their former ace Sam Kimber,15 to dominate the Interstate League. The club won 13 of 14, including a pair of Terry shutouts, on the way to first place. In late September, Terry won the pennant clincher over Harrisburg.16 He finished 16-9 in league play, with a dazzling 1.38 ERA and 1.12 WHIP.

Byrne parlayed the club’s success into an 1884 berth in the American Association. Entering the season, the Brooklyn Union asserted that club management “cannot prize … Terry too highly, for they must acknowledge now that he is their winning card.”17 Terry played right field in the team’s first championship (regular season) match, a loss to the Washington Nationals, then earned Brooklyn’s first major-league win from the pitcher’s box the next day.18 Thirteen hits (five for extra bases) in his first 10 games also earned him a spell batting cleanup.19

Terry quickly became a “pet of the fair patrons of the game.” After he tripled in a May game, one called him “too splendid for anything.”20 A trio of constables found Terry less than splendid when they walked onto a Columbus ballfield on a June Sunday and arrested him and eight other ballplayers for violating that city’s blue laws. The game was allowed to go on to prevent 3,000 attending fans from rioting, after which the players settled matters with a local justice.21

On August 2, Brooklyn manager Taylor picked the not-yet-20-year-old Terry to fill in for an umpire unable to work a home game with the Baltimore Orioles.22 He thus became one of a dozen teenaged fill-in umpires in major-league history. 23 Given how players, managers and fans often heaped abuse (verbal and physical) on umpires in the 1880s, this showed extraordinary confidence in Terry’s ability to perform under pressure – and defend himself. Terry eventually substituted for missing arbiters 10 times during his playing career.

Terry finished the season 19-35 for the ninth-place Atlantics, with 54 complete games and a decent .233 batting average. A good fielding pitcher, though, he was not. Terry committed a career-high 34 errors there, second most in the league.

Byrne added several players from the defunct National League Cleveland Blues to his 1885 squad, now known as the Grays, and handed the club’s reins to former Blues manager, Charlie Hackett. Terry underperformed to start the season, going 5-10 – Sporting Life said he was going backwards – then complained he wasn’t getting enough support from the “Cleveland clique.”24 A schism had developed between the former Blues and the Brooklyn incumbents, marked by a lack of harmony and unequal treatment. Byrne fired Hackett and took over managing himself. He soon made Terry an everyday outfielder, where he drew raves from the press.25 Terry pitched only sporadically the rest of the year, finishing with a dismal 6-17 record and a lowly .170 batting average.

Despite that uninspiring performance, heading into the 1886 season, Terry was “safe to say, the most popular man on the team.”26 He turned his mound performance around, compiling a solid 18-16 record with a 3.09 ERA and only one home run allowed in 288 1/3 innings. He gave up two earned runs or fewer in nine of his first 11 starts, including a one-hit shutout in which he retired the first 19 batters.27 July 17-24 was the most dominating week of Terry’s career. He fanned a career-high 11 Louisville Colonels,28 defeated the first-place St. Louis Browns on three hits,29 then no-hit them two days later – according to some accounts. The New York Times, Brooklyn Eagle, and St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported Terry hadn’t allowed a hit in his 1-0 masterpiece, but the New York Tribune credited Arlie Latham with a single on a ball that Brooklyn shortstop Germany Smith couldn’t field.30 The official scorer (HenryChadwick) had agreed with the majority, giving Terry his first no-hitter. When Terry next faced St. Louis, three weeks later, he surrendered 18 runs in seven innings.31 That still stands as the most allowed in major-league history by a pitcher in his next start against a team after no-hitting them.32

After a winter that included throwing balls into a mattress-backed frame that simulated a strike zone, Terry had grown into a 5-foot-11-inch, 168-pound frame of his own.33 For much of the 1887 season, he split his time between pitching and playing in the outfield, or occasionally shortstop. He won as many as he lost and collected a league-leading three saves (as credited retroactively). His offensive production was noteworthy, hitting .293 (tied for second on the team), with 27 stolen bases and a career-high 65 RBIs. In maybe the most comical outing of Terry’s career, during a June contest at St. George Grounds, a Mets outfielder “disappeared among the antiquities” when chasing a fly ball “hit to the Babylonian district,” sets from an outdoor theatrical production left in the outfield between performances.34

In September 1887, Terry was first referred to as “Adonis” in print. The New York Tribune did so in reference to actor Henry E. Dixey, who portrayed the Greek god of beauty and desire in a popular Broadway show, Adonis.35 Love, marriage, and a baby carriage soon followed. Terry wed the former Cecilia E. Moore of Brooklyn that month, and she delivered their first child, a daughter named Cecilia M., the following January.36

In addition to a new family, 1888 brought Terry new teammates. Three were standouts acquired from the three-time defending champions St. Louis Browns.37 Also joining were several former New York Metropolitans (Byrne had bought and then disbanded that franchise the previous October). “True, there will be some lack of harmony,” said a Sporting Life prognosticator about all the new faces, “but still I think that team from the City of Churches will be so strong…that it will win the championship anyhow.”38 The press also took note of how many new players’ brides were attending preseason games, three of Terry’s teammates having also gotten hitched in the offseason. By mid-April, several Brooklyn newspapers had begun calling the team Bridegrooms with a capital “B.”39

On May 27, 1888, Terry authored his second no-hitter, against the Louisville Colonels at Ridgewood Park in Queens.40 He fanned eight in the 4-0 victory, most of them swinging. Terry’s “well disguised change of pace bothered the Louisville batsmen greatly,” according to the Brooklyn Eagle.41 In his next start, “the personification of coolness” hit a game-ending single in the bottom of the 13th that “transformed an anxious, orderly and well-behaved assemblage into bedlam.”42 The win put Brooklyn in first place, where they stayed for seven weeks.

A badly spiked hand and lame right arm kept Terry in and out of the rotation until mid-September.43 Ten days after pain limited him to just three pitches in a start, he was suspended without pay.44 Terry, as he would several times again in his career, accepted the draconian 19th-century practice of suspending injured players, saying he could “find no fault with club for laying me off.”45 He pitched once more in mid-October, but by then St. Louis had won another title. Despite missing so much time, Terry had maybe the finest pitching year of his career: posting career lows in ERA (2.03) and WHIP (1.09), with a league-leading 6.4 strikeouts per nine innings.

A pioneer in ballplayer conditioning and injury prevention, Terry took up bicycle riding that winter to build leg strength and improve overall fitness. A few years earlier, he’d become a devotee of American handball for strengthening throwing arms.46 Terry combined these two sports with other workouts in offseason training programs followed by many fellow ballplayers.47 Later in his career, Terry focused on upper body strengthening, promoted massage to restore tired arms, devised a pulley device for exercising throwing arms, and called for the elimination of spiked shoes, which he considered weapons.48

Terry struggled early in 1889 with the new rule giving batters a walk after only four balls, walking seven in his first start and eight in several others that spring. Yet as it developed, he came away with his first 20-win season. On August 31 he defeated the Kansas City Cowboys to put the Bridegrooms in first place. Back-to-back victories by Terry over the Columbus Solons, with his two triples pacing the offense in the second game, earned him a $500 bonus and Brooklyn the Association crown.49 Terry’s .300 batting average for the year also made him the circuit’s top hitting pitcher.50

“Parisian” Bob Caruthers topped the club with 40 regular-season wins, but it was Terry who led Brooklyn into the 1889 World Series. In Game One, he outlasted Tim Keefe and the favored NL New York Giants for a 12-10 win at the Polo Grounds.51 He won an abbreviated Game Four at Washington Park,52 but lost an 11-inning Game Six pitcher’s duel with Hank O’Day on a game-ending single by John Montgomery Ward.53 Back-to-back losses by Terry in Games Eight (a blowout) and Nine (a 3-2 comeback win) gave the championship to the Giants, six games to three.54 A humble Terry received a large diamond solitaire stud at a surprise party a few weeks later, saying he hoped he “would not be found wanting” in the future.55

Brooklyn newspapers speculated that Terry, like so many others, might join Ward’s Players League ahead of the 1890 season.56 However, he stayed with the NL-bound Bridegrooms. That loyalty paid off, as he outpolled Ward (player/manager for the new Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders of the Players League) in a contest for the most popular Brooklyn ballplayer initiated by a St. Augustine, Florida, church. (The church was located near where the Bridegrooms held their pre-season training camp.) Collecting a dime minimum for each vote, the church raised over $12,000 for its building fund, and awarded Terry a baseball-themed gold badge, set with 16 diamonds.57

It took Terry until his sixth start in 1890 to earn his first NL victory, over Ezra Lincoln and the Cleveland Spiders.58 Injuries to Brooklyn’s regular outfielders landed Terry and Caruthers in the outfield in most games they weren’t pitching.59 In late July, manager Bill McGunnigle went to a two-man rotation of Terry and Tom Lovett. Terry won 11 of his next 12 decisions to put Brooklyn in first, including a game in which “the welkin rang” (the angels sang) for five minutes after his first-inning three-run homer off Boston ace John Clarkson.60

“Brooklyn’s chances depend on how much Terry can stand,” noted Chicago player/manager Cap Anson.61 Stand he did – Terry played in Brooklyn’s last 64 games. Over that span, he won both ends of an August 20 doubleheader with Philadelphia, the third game of a September 1 tripleheader against Pittsburgh after having played left field in the first two, and the pennant clincher over Cincinnati.62 He won a career-high 26 games, and also notched personal bests in outfield fielding percentage (.930), home runs (4), and stolen bases (32). The last set a record for NL (or AL) 20-game winners.63

Terry continued to serve as the team’s workhorse in the 1890 World Series against the AA champion Louisville Colonels. He spun a two-hit shutout to defeat 34-game winner Scott Stratton in Game One, then played right field in Game Two.64 Terry pitched in Game Three, which ended in a tie, and moved to left field for Game Four, which Louisville won. On Saturday, October 25, stationed in center field for Game Five, Terry’s run-scoring double, his only hit of the Series, capped the scoring in a Brooklyn win.65 On Monday, October 27, he lost to Louisville in Game Six on a cold and blustery day, allowing nine runs on 12 hits. Terry sat out Game Seven, a Brooklyn loss. With the Series tied 3-3-1, bad weather and low attendance convinced both teams to postpone the last two games until spring. The NL and AA were at each other’s throats in early 1891, and so the Series was never finished.66

The demise of the Players League opened the door for Charles Byrne to hire John Ward as the captain and player/manager for the 1891 Grooms, as they were now called. Terry delayed signing his contract, but said, “I am certain that under Ward’s direction I will pitch better ball than ever before.”67 He couldn’t have been more wrong. An outfield collision in May injured his ankle, which affected his pitching mechanics and gave him arm problems.68 Ineffective for months, Terry allowed double-digit runs in his last two starts.69 He was then suspended for the last nine games of the season.70 He finished 6-16 for the sixth-place Grooms, with an ERA well above league average. After the season, the Brooklyn Eagle declared, Terry’s “usefulness as a pitcher is … at an end.”71

Going into the 1892 season, first Terry’s pay was cut (by $500).72 Then he got the axe two months into the schedule after not appearing in a single game. Nonetheless, the Brooklyn Eagle predicted he’d be “snapped up by any one of six clubs,” and they were right.73 Two days later, Terry signed with the Baltimore Orioles. However, his time in Charm City was brief. With multiple newspapers reporting that he’d already been flipped to Pittsburgh, Terry lost a June 16 contest in which he allowed seven runs on seven hits and seven walks.74 Triple-7s turned out to be a good omen for Terry, but not at first.

The Pirates had indeed acquired Terry, in exchange for infielder Cub Stricker. He won his debut and in his next start shut out Cincinnati on two hits, but the Pittsburg Dispatch still felt the team should’ve gotten another (better) pitcher for Stricker.75 Terry suffered a few ugly losses after taking ill in early July, which put him on the brink of being released again. Manager Al Buckenberger gave him another chance, though.76 Terry responded – with a delivery that “approached the texture of silk in its fineness,” he won his next nine decisions, and another five straight to end the season.77 The Pittsburg Dispatch unabashedly declared Terry “without doubt … the best pitcher in the country to-day.”78 Terry finished the year 18-7 with Pittsburgh, posting a 2.51 ERA. He also earned a $1,000 bonus and a $2,800 contract for 1893.79

Terry returned to Brooklyn in the offseason, where he worked out with former teammates and coached local college nines in early spring, as he’d done since 1890.80 Despite pitching from a pitcher’s plate that by then was 60 feet, six inches from home, Terry won his first six decisions in 1893. Back problems forced him to cut several starts short, though, and his record tumbled. He was used sparingly after a June 30 game in which he and a pair of relievers walked 15 Grooms.81 Terry wound up with a winning record, but the Pirates finished a disappointing second.

In the midst of his summer swoon, Terry uncharacteristically confronted umpire Tim Hurst at a Chicago hotel. After Terry complained that Hurst had given Pittsburgh the wrong end of his decisions, Hurst said he’d “disfigure [Terry’s] rather handsome face” if the claim wasn’t withdrawn. Terry stood firm and vowed to “increase the homeliness that glares out between Hurst’s brow and chin.”82 Luckily, the two never came to blows.

Terry pitched one dreadful game for the Pirates in April 1894, then was let go. He tried out with Brooklyn,83 but was signed by the Chicago Colts. In 21 starts for Chicago he went 5-11, including allowing 25 runs in a loss to Boston and 20 in the season finale, during which the Baltimore Orioles “ran in scores ad libitum [at their pleasure].”84. For the season (including his time with Pittsburgh), Terry had career single-season highs in ERA (6.09), WHIP (2.20), and walks per nine-innings (7.0). On offense, he had career highs in batting average (.347) and OPS (.847). Sporting Life called Terry a “ball killer,” but also said his best days were behind him.85

They weren’t. In 1895 Terry experienced “his third time on earth.”86 He won 21 games and registered an ERA that was below both league and team averages. The Pittsburgh Post declared that Terry had found his youth after collecting four hits in a May win over Brooklyn.87 The Chicago Chronicle marveled at how his “artistic assortment of pretzel curves” befuddled opponents and delighted the Chicago faithful.88

Terry was less than delighted when he was sent home before Opening Day in 1896, told he wasn’t “fit to play in the cold.”89 He spent a few weeks pitching for a Chicago semipro team, the Whitings.90 Upon his return in early May, he triumphed.91 In June, Terry shaved off his trademark mustache in the middle of a three-game personal losing streak that grew to six.92 Two weeks later, Terry surrendered four home runs and a single to two-time .400 hitter Ed Delahanty in a game that he won, 9-8. With Chicago up by two entering the ninth, Anson threatened to fine every Colts “the price of three meals at World’s Fair rates” if any Phillies were on base when Delahanty next batted. Terry and company complied, so when Delahanty’s fourth home run sailed over the head of center fielder Bill Lange, the lead remained intact.93

Terry played his last major league game on April 27, 1897, losing 10-4 to the Browns at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. As the umpire started the game, electric fires broke out in a dozen locations in the grandstand. “For two breathless minutes, the time it took a workman to reach the roof of the grandstand and cut the wire, a panic held itself in readiness to break forth, and baseball was forgotten.”94 Twelve months later, the grandstand was destroyed in a fire that seriously burned at least 100 people and took one life.95

Terry spent the balance of that season and the next playing for former Pirate batterymate Connie Mack with the Western League’s Milwaukee Brewers. Terry’s debut was a “howling success,” allowing only a hit or two, depending on the newspaper.96 In September, he no-hit former Colts teammate Bill Hutchison and the St. Paul Saints.97 Terry led the third-place Brewers pitching staff with a sparkling 22-10 record and 1.75 ERA.

When offered an 1898 contract for $200 a month, Terry balked, saying he could make more at the billiards parlor where he’d begun working, as well as playing semipro ball.98 A deal was struck where Terry played only home games.99 After an up-and-down start, he won 10 straight starts, interrupted by a one-month suspension for being out of shape.100 Terry defeated former Colts teammate Buttons Briggs and the Detroit Tigers in his final start, then called it quits.101

Terry took a job umpiring NL games in June 1900, but left after two months, unwilling to put up with poor treatment on the field and off. He needed a police escort to escape a mob at the Polo Grounds, goaded on by the Giants manager George Davis, whom Terry had ejected earlier.102 That same day, the Cincinnati Enquirer claimed “mortification of the brain tissues” made Terry unfit to work games in the Queen City.103 Sporting Life said he resigned in disgust.104 Nonetheless, Terry claimed he enjoyed the “actual work of umpiring.”105 Though no longer interested in doing it regularly, he umpired two American League games in Milwaukee the next year.106

Terry played semipro ball on and off after he retired,107 but bowling became his passion.108 He’d first bowled when living in Brooklyn, and enjoyed competing in New York area leagues with Brooklyn secretary Charlie Ebbets.109 Terry managed local bowling alleys in Milwaukee, opened his own in 1900, and introduced tenpin bowling to the city.110 He also sponsored teams in various tournaments, including one 1904 event that “seemed like a convention of old-time baseball players.”111 Terry successfully lobbied the American Bowling Congress to hold its 1905 national tournament in Milwaukee, and toured the country promoting it.112

Adonis Terry died of pneumonia at his Milwaukee home on February 24, 1915.113 “No one feels more keenly the death of ‘Adonis’ Terry… than I do” said former Colts teammate Clark Griffith. “He was one of the baseball men after whom I have always tried to pattern my career.”114 The Pittsburgh Gazette Times called Terry “a perfect specimen of manhood, on and off the field.”115

In early 1924, the New York World heralded the arrival of another Terry in the National League who held the promise of becoming as famous as Adonis.116 William Harold “Bill” Terry went on to a Hall of Fame career as a first baseman and manager for the New York Giants.

Marking the 120th anniversary of his first no-hitter, the city of his birth – Westfield, Massachusetts – declared Adonis Terry Day in July 2006.117 Fifteen years later, Terry, the ship carpenter’s son from Westfield who’d carved out a long and eventful baseball career, was inducted into the Western Massachusetts Baseball Hall of Fame.118

Last revised: July 18, 2022 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Russ Walsh.

Sources

The author compiled game logs for the 1883 Brooklyn Greys and for Terry’s complete professional career from games summaries and box scores published in newspapers which regularly covered the teams on which he played: primarily the Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn Union, Brooklyn Times, New York Sun, New York Times, Pittsburg Press, Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, Pittsburg Dispatch, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Chronicle, Chicago Inter Ocean, Milwaukee Journal, and Sporting Life. He also obtained pertinent material from Ronald G. Shafer’s SABR biography of Charles Byrne and Doug Skipper’s SABR biography of Connie Mack. In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted MyHeritage.com, FamilySearch.com, Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, Stathead.com, and Statscrew.com.

Notes

1 Supporting the generalization published in the New York Sun that Terry was the fastest, Sporting Life reported how one Pittsburgh fan had timed various pitchers’ deliveries in 1886 and found Terry’s the fastest of all. “Famous Pitchers,” New York Sun, January 29, 1888: 8; “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, August 18, 1886: 5.

2 “Byrnes Brooklyn Boys,” Sporting Life, October 23, 1889: 2; J.F. Donnelly, “Brooklyn Brevities,” Sporting Life, May 8, 1889: 3.

3 Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, Mark Rucker, ed., Baseball’s First Stars, Volume 2 (Cleveland: SABR, 1996), 164.

4 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (Free Press: New York, 2003), 135.

5 “Terry’s Effective Whitewash,” New York Herald, May 31, 1891: 18.

6 Henry Chadwick, “Fight Views,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1897: 6. Chadwick was an ardent Terry supporter throughout the latter’s career. See, for example, Henry Chadwick, “Chadwick’s Chat,” Sporting Life, September 4, 1889: 6.

7 Marriage Registry, Fall River, July 22, 1863; “The Draft,” Fall River Evening News, July 23, 1863: 1.

8 Circle, “Pittsburg Pencillings,” Sporting Life, August 26, 1893: 9; “Athletics and Sports,” Brooklyn Standard Union, December 8, 1888: 4..

9 “The Brooklyns,” New York Evening World, April 27, 1891: 2. Author Daniel Genovese reported that Terry split his time in 1882 between the Rosedales and the Racquet Club of Ludlow team. As Bridgeport and Ludlow are separated by 90 miles, this would’ve been a major challenge for Will to juggle along with his factory job. Daniel L. Genovese, The Old Ball Ground, Volume One (West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Infinity Publishing Co, 2004), 184.

10 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, October 14, 1882: 3.

12 “The Brooklyn Grays,” Sporting Life, July 1, 1883: 3.

13 Brooklyn’s opponent was the Jaspers of Manhattan College. Terry was also the starting pitcher in the first pre-season game Brooklyn played after joining the major league American Association, against the National League Cleveland Blues, on April 12, 1884. “Out-Door Sports,” Brooklyn Union, June 21, 1883: 4; “The Brooklyn Club,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 559; New York Times, April 13, 1884: 2.

14 This game was the first of many Ladies Day crowds Terry entertained in his career. “Brooklyn News,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1883: 4.

15 Kimber was one of five players acquired by Byrne when the first-place Merritts decided to disband in July 1883. Four of the five (Kimber, first baseman Charlie Householder, second baseman Bill Greenwood, and shortstop Frank Fennelly) became regulars for the Brooklyn nine as soon as they arrived. Ronald Shafer, Charles Byrne SABR bio, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/charles-byrne/

16 “Base-Ball Contests,” New York Times, September 30, 1883: 2.

17 “Out-Door Sports,” Brooklyn Union, April 22, 1884: 4.

18 Terry also led the Brooklyn offense in their first win, with a pair of hits. “The Championship Season,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 2, 1884: 2; “Base Ball Contests,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 3, 1884: 1.

19 See, for example, “Base-Ball Games,” New York Times, May 30, 1884: 2.

20 “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 1, 1884: 10.

21 “The Sunday War,” Sporting Life, July 2, 1884: 6.

22 In the 1880s, home teams were typically responsible for obtaining fill-in umpires to replace scheduled umpires unable to perform. “The Home Nine Wins,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 3, 1884: 2.

23 Major league baseball lists 22-year-old Billy Evans as the youngest umpire in major league history, but that designation appears to exclude fill-in umpires. The youngest major league fill-in umpire was Kid Carsey, who was two months shy of his 19th birthday when he served as part of a two-man umpiring crew for the first game of a September 7, 1891 doubleheader between the American Association Washington Statesmen and Columbus Solons.. “Umpiring Timeline,” MLB website, https://www.mlb.com/official-information/umpires/timeline, accessed June 15, 2022.

24 “From the City of Churches,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1885: 3; “The Cleveland Clique,” Sporting Life, June 24, 1885: 5.

25 Terry started 47 games in the outfield, initially in left field, later shifting him to center field and then right field. His game-saving, ninth-inning catch in left field of a line drive from eventual batting champ Pete Browning earned Terry recognition from Sporting Life. Despite the glowing praise, Terry’s .833 outfield fielding percentage was the lowest of Brooklyn’s outfielders. “Base-Ball,” Brooklyn Union, September 4, 1885: 3; “Games Played July 15,” Sporting Life, July 22, 1885: 3.

26 “Brooklyn’s New Team,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 28, 1886: 16.

27 “Not a Run for Baltimore,” New York Tribune, June 27, 1886: 9.

28 Louisville pitcher Toad Ramsey matched Terry’s feat in the game, striking out 11 Brooklyn batters. “The Brooklyns Win,” New York Times, July 18, 1886: 2.

29 “Brooklyn Defeats St. Louis,” New York Times, July 23, 1886: 2.

30 “The Champions ‘Chicagoed’,” New York Times, July 25, 1886: 5; “Not a Single Safe Hit,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 25, 1886: 16; “Brooklyns, 1; St. Louis Browns, 0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 25, 1886: 9; “St. Louis Men Beaten,” New York Tribune, July 25, 1886: 8.

31 “Brooklyn’s Poor Showing,” New York Times, August 16, 1886: 8.

32 Based on the author’s compilation for pitchers next starts after complete game no-hitters from 1876 through the 2021 season, as listed by Baseball-Reference.com. The compilation was based on home team newspaper accounts for games played before 1901 and Baseball-Reference.com data for games played after 1900. For 277 of the 300 no-hitters listed, pitchers had another start in their career against the team that they’d no-hit. The next highest number of runs allowed by a pitcher in his next start against a team he’d no-hit was nine, by Brooklyn’s Tom Lovett against the New York Giants on June 25, 1891 after he’d no-hit them three days earlier, Mal Eason of the Brooklyn Superbas against the St. Louis Cardinals on July 30, 1906 after he’d no-hit them ten days earlier, and Jesse Barnes of the New York Giants against the Philadelphia Phillies on May 30, 1922 after he’d no-hit them three weeks earlier.

33 “Gossip About Ball Players,” New York Sun, March 18, 1887: 3; “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1887: 10.

34 “Played Without Errors,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 26, 1887: 16..

35 “Two Players in Collision,” New York Tribune, September 11, 1887: 16; “Henry E. Dixey: Adonis,” Travalanche website, https://travsd.wordpress.com/2013/01/06/stars-of-vaudeville-559-henry-e-dixey/, accessed June 2, 2022. Daniel Genovese in The Old Ball Ground: Volume One claims that Chicago sportswriter Hugh Keogh [sic] first called Terry “Adonis” a year earlier, while describing a game between Brooklyn and Chicago. Chicago did not have a franchise in the American Association in 1886 (or any other year), so the Keogh story, if true, would have described a pre-season or in-season exhibition game. In compiling game logs for each of Terry’s major league seasons, the author did not find any pre-season or exhibition games played between Brooklyn and any Chicago team in 1886 or 1887. The Old Ball Ground, 195.

36 “New York, New York City Marriage Records, 1829-1940,” database, FamilySearch, William Terry and Cecilia Moore, 27 Sep 1887, citing Marriage, Manhattan, New York, New York, United States, New York City Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 1,556,693, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:24MV-JRD, accessed April 20, 2022; “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 23, 1888: 4; “Death of Bill Terry Recalls Brooklyn Triumphs,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 1, 1915: 8.

37 In November 1887, Byrne purchased 20-game-winning pitchers Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, plus catcher Doc Bushong. David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 146.

38 “The Pennant Race,” Sporting Life, January 4, 1888: 4.

39 “The Brooklyns Batted,” Brooklyn Union, April 10, 1888: 2; “Another Win for Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 10, 1888: 3.

40 The Bridegrooms played Sunday games in Queens to avoid Brooklyn’s tougher blue laws enforcement. Bill Lamb, Ridgewood Park (New York) SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/ridgewood-park-ny/

41 “Not a Base Hit,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 28, 1888: 1.

42 “Two Games for Brooklyn,” New York Times, May 31, 1888: 3.

43 “The Hard Work of Sport,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 24, 1888: 6; “The Brooklyns Win,” Brooklyn Standard-Union, August 2, 1888: 3.

44 “Honors Even,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 10, 1888: 1; “Chips from the Diamond,” New York Sun, September 20, 1888: 3.

45 “Gossip of the Ball Field,” New York Sun, September 30, 1888: 8.

46 “To Train Base Ball Players,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 5, 1888: 16; “Barrier Playground,” New York City Department of Parks & Recreation website, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/barrier-playground/history#:~:text=It%20quickly%20caught%20on%20with,version%20is%20the%20most%20popular., accessed June 2, 2022.

47 See for example, “The Brooklyn Team’s Training,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 28, 1888: 2; “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 24, 1889: 20; “Dave Foutz in Training,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 7, 1894: 8.

48 “Sporting,” Pittsburg Press, January 31, 1894: 5; “Massage Treatment,” Sporting Life, May 1, 1897: 13; “Base Ball Gossip,” Kansas City (Missouri) Star, January 14, 1897: 3; “Spikes Unnecessary,” Sporting Life, November 14, 1896: 6.

49 Terry’s batterymate, Bob Clark, also earned a $500 bonus for the victory. “The Brooklyns Get There,” Brooklyn Times, October 15, 1889: 4.

50 “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, December 25, 1889: 4.

51 “One for Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 19, 1889: 3.

52 Darkness brought the game to a close after six innings. “Are Not Babies,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 24, 1889: 1.

53 “Terry Tried,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 26, 1889: 1.

54 “The World’s Series,” Philadelphia Times, October 29, 1889: 4; “The Fight Over,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 30, 1889: 1.

55 “Gave Terry a Solitaire,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 10, 1889: 1.

56 “The Sporting World,” Brooklyn Citizen, November 23, 1889: 3.

57 Terry collected 1,344 votes to 1,093 for Ward. The badge included four gold bars in the outline of a baseball diamond, resting on a pair of miniature crossed bats, with real diamonds representing each base and another in the center. The badge was said to cost $200 (nearly $6,000 in 2021 dollars). “Votes for Base Ball Players,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 17, 1890: 6; “Terry the Most Popular,” 12.

58 “Winning Ball,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 29, 1890: 1.

59 “Won by a Crippled Nine,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 1, 1890: 2.

60 This was one of Terry’s two victories over the future Hall of Famer in six career decisions. J.F. Donnolly, “A Boom in Brooklyn,” Sporting Life, August 9, 1890: 11.

61 “Anson’s Changed Opinions,” Sporting Life, August 9, 1890: 13.

62 “Won by Fine Batting,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 21, 1890: 3; “Bravo, Grooms,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 2, 1890: 2; “Brooklyn (N.L.), 5; Cincinnati (N.L.), 1,” New York Sun, September 25, 1890: 4.

63 “Parisian” Bob Caruthers of those same 1890 Brooklyn Bridegrooms and Charlie Ferguson of the 1887 Philadelphia Phillies have the second-most stolen bases in a year by a 20-game NL (or AL) winner, with 13 each. Caruthers holds the major league record for stolen bases by a 20-game winner, with 49 for the 1887 St. Louis Browns of the American Association.

64 “Brooklyn Takes the First Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 18, 1890: 3; “Errors Lost the Game,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 19, 1890: 5.

65 “Brooklyn Wins Again,” New York Times, October 26, 1890: 8.

66 David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (New York: Lyons and Burford, 2004), 199; John Thorn, “The Last 19th-Century World Series,” April 6, 2018, Our Game website, https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/the-last-19th-century-world-series-8e96ff585ff9, accessed June 13, 2022.

67 “Foutz and Burns in Line,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 18, 1891: 4.

68 “Ward Will Play Today,” Brooklyn Citizen, May 19, 1891: 3; G.H. Dickinson, “New York News,” Sporting Life, August 1, 1891: 2; “Dissatisfied with the Home Teams,” New York Tribune, August 30, 1891: 20.

69 After the first of the two debacles, the Brooklyn Eagle suggested Terry play the outfield instead of pitching anymore. “A Change Badly Needed,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 28, 1891: 3; “Ward’s Men Outplayed,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 13, 1891: 8.

70 Sporting Life reported the suspension as being “until he is in condition.” “News, Gossip and Comment,” Sporting Life, September 26, 1891: 10.

71 “Working Well,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 29, 1891: 1.

72 “His Tenth Season,” Brooklyn Citizen, February 24, 1892: 3.

73 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 11, 1892: 1.

74 “Proposed Trade for Stricker,” Baltimore Sun, June 16, 1892: 7; “Quite a Shake Up,” Pittsburg Dispatch, June 16, 1892: 8; “Dire Disaster,” Baltimore Sun, June 17, 1892: 6.

75 “Won a Game and Lost One,” Pittsburgh Post, June 22, 1892: 6; “Terry’s Fine Work,” Pittsburg Dispatch, June 25, 1892: 8. “Terry’s Fine Work,” Pittsburg Dispatch, June 25, 1892: 8.

76 Pirates captain Tom Burns (who’d also briefly managed the team earlier in the year) had prepared Terry’s release papers after a “very unsteady” four-inning outing on July 7, and surrendering 16 hits in a July 11 loss to Brooklyn. “Sporting,” Pittsburg Press, September 3, 1892: 5; Circle.

77 “Sporting,” Pittsburg Press, August 12, 1892: 5.

78 “Terry’s Fine Work,” Pittsburg Dispatch, October 9, 1892: 6.

79 Terry was the only Pirate to receive a bonus for the 1892 season, awarded to him for winning over 65% of his starts. “Pittsburg Finances,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 1; “Editorial Views, News, Comment,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1892: 2; Circle, “Pittsburg Pencillings,” Sporting Life, November 5, 1892: 3.

80 Terry began training ballplayers for Connecticut’s Wesleyan College in 1890, for Columbia in 1893, Princeton in 1894, and Brown in 1895. “Sports for Next Summer,” New York Evening World, January 30, 1890: 3; “Columbia College Athletes,” New York Sun, February 24, 1893: 4; “Terry Coaching at Princeton,” New York Times, March 2, 1894: 9; “Personal,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1895: 12.

81 “We Are Disgraced,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, July 1, 1893: 6.

82 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, August 9, 1893: 2.

83 The Old Ball Ground, 234.

84 “Was a Fitting End,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 1, 1894: 8.

85 W.A. Phelon, Jr., “Chicago Chirps,” Sporting Life, April 27, 1895: 3; W.A. Phelon, Jr., “Chicago Gleanings,” Sporting Life, December 1, 1894: 2.

86 W.A. Phelon, Jr.,” Chicago’s Grief,” Sporting Life, September 7, 1895: 6.

87 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, May 20, 1895: 6.

88 “Chicago Baseball Team,” Chicago Chronicle, June 30, 1895: 11; “Colts Capture One Game,” Chicago Chronicle, May 31, 1895: 8.

89 “Make-Up of the Team,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1896: 8.

90 Terry’s outings for the Whitings included one game against the University of Chicago nine coached by future football legend Amos Alonzo Stagg. “Varsity Team Work Poor,” Chicago Chronicle, April 26, 1896: 14.

91 Terry retired the final 18 batters he faced in the game, an 11-3 victory over Brooklyn. “Chicago Wins the Fourth,” Chicago Chronicle, May 7, 1896: 5.

92 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, June 27, 1896: 5.

93 “Thrown Down by an Old Timer,” Philadelphia Times, July 14, 1896: 8. Ironically, Delahanty, who met his end getting swept over Niagara Falls, hit three of his four homers off Terry’s curveball, which early that season the Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star said, “drops like Niagara.” “A Record in Hitting,” (Richmond, Indiana) Palladium, August 6, 1911: 3; “Baseball Talk,” Rockford Morning Star, April 21, 1896: 2.

94 “Brown Paint for Terry,” 8.

95 Joan M. Thomas, Robison Field (St. Louis) SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/robison-field-st-louis/

96 The Chicago Tribune game summary and box score credited Terry with a one-hitter. A Minneapolis Times game summary and linescore reported Terry had allowed two hits. “Milwaukee, 6; Detroit, 1,” Chicago Tribune, May 21, 1897: 6; “Adonis Terry’s Debut was a Howling Success,” Minneapolis Times, May 21, 1897: 2.

97 The Detroit Press credited Hutchison with an opposite field ninth inning single, while the Chicago Tribune credited Terry with a no-hitter. The official scorer ruled Hutchison had reached base on an error. “Brewers Won a Notable Contest,” Detroit Free Press, September 15, 1897: 6; “Milwaukee, 3; Minneapolis, 0,” Chicago Tribune, September 15, 1897: 4; H.H. Cohn, “Milwaukee Mems,” Sporting Life, September 25, 1897: 13.

98 “‘Adonis’ Terry Kicking, Too,” Detroit Free Press, February 13, 1898: 6.

99 “Terry to Play in Home Games,” Milwaukee Journal, March 7, 1898: 9.

100 “Baseball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, June 1, 1898: 5; Terry’s win streak was stopped when the Brewers were no-hit by St. Paul’s Bill Phyle. “Phyle was in Fine Form,” St. Paul Globe, August 21, 1898: 10.

101 Milwaukee, 6-6; Detroit, 2-1,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 5, 1898: 5.

102 “Great Plays by Dexter,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1900: 9.

103 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 3, 1900: 4.

104 “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1900: 3. Outrage over Terry’s failure to eject the Cardinals Dan McGann and the Phillies Harry Wolverton, whose fight required police intervention to break up, appeared to precipitate his resignation, but Young claimed he’d submitted his resignation beforehand. N.E. Young, “Mr. Young Abused,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1900: 4; “Milwaukee Mems,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1900: 9.

105 “Milwaukee Mems,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1900: 9.

106 “In the World of Sport,” Detroit Free Press, September 1, 1901: 28; “Errors in the Tenth,” Washington Times, August 31, 1901: 3; “One Run Their Portion,” Washington Times, September 1, 1901: 5.

107 The day after Terry’s last game with Milwaukee he pitched for the Racines against the Page Fence Giants. In 1899, he pitched for the Racines, for the Razaals in the Milwaukee league, and for the Watertown nine. He played for an un-named semipro team in 1901, and in 1903 played for an unnamed team in the Milwaukee Commercial League. “Racines Lost Both Games,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, September 6, 1898: 8; “They Bat Terry’s Pitching,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1899: 4; “Portage Filled with Visitors,” Portage (Wisconsin) Register, June 21, 1899: 1; “Watertown, 9; Jefferson, 0,” Watertown (Wisconsin) News, July 25, 1899: 1; “Baseball Briefs,” Detroit Free Press, April 26, 1901: 10; “Base Ball Yesterday,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Leader, April 20, 1903: 6.

108 Terry might have been too ardent in pursuing his bowling ambitions on one occasion. In 1903 he was the subject of an arrest warrant for having violated child labor laws. Terry was in Indiana when it was issued, and its unclear how the complaint was resolved. “Warrant for Adonis Terry,” Milwaukee Journal, January 28, 1903: 9.

109 Terry competed for several years with Ebbets on Brooklyn bowling teams and continued to play against former teammates in Brooklyn leagues, like Doc Bushong, even after moving on to play with the Pirates. “Acme Hall Bowling,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 10, 1891: 6; “Irquois [sic] on the Toboggan,” Brooklyn Citizen, December 12, 1895: 6.

110 “Games in the Bowling Leagues,” Chicago Tribune, January 27, 1900: 7; “Bill Terry Passes Away,” Watertown News, March 2, 1915: 2.

111 “Old Players are Bowlers,” Pittsburg Press, January 25, 1904: 10.

112 “Doings of Local Bowlers,” Chicago Daily News, December 21, 1903: 6; “Good Season for Bowlers,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1905: 62..

113 He contracted the pneumonia at his bowling alley according to one report. Survived by his wife Cecilia, two children (Cecilia and William T.), and several grandchildren, Terry was cremated. Baltimore Evening Sun, February 25, 1915: 8; “Death of Billy Terry Recalls Former Triumphs of Brooklyns,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 25, 1915: 18; “Bill Terry Passes Away,” 2..

114 “Griffith Honors Kavanaugh,” Washington Times, February 25, 1915: 12.

115 “Death of Bill Terry Recalls Former Triumphs,” 8.

116 “Giants Garner Real Clouter in Bill Terry,” Great Falls (Montana) Tribune, March 16, 1924: 8.

117 Mayor Richard F. Sullivan, Jr., Proclamation, Office of the Mayor of the City of Westfield, July 2006, https://www.facebook.com/WillianHTerryAdonis/, accessed May 26, 2022.

118 “Western Massachusetts Baseball Hall of Fame,” Valley Blue Sox website, http://valleybluesox.pointstreaksites.com/view/valleybluesox/community/western-massachusetts-baseball-hall-of-fame, accessed June 7, 2022.

Full Name

William H. Terry

Born

August 7, 1864 at Westfield, MA (USA)

Died

February 24, 1915 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.