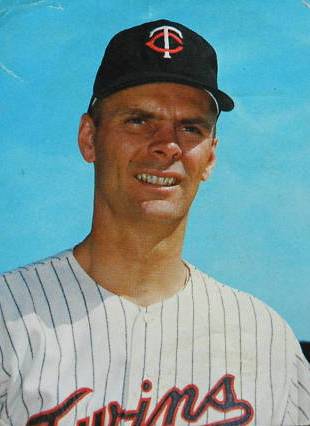

Jerry Kindall

Jerry Kindall had no trouble making it to the major leagues. All the 21-year-old University of Minnesota 1956 All-American infielder had to do was sign on the dotted line, and the next day he was in Chicago wearing a Cubs uniform.

For Kindall, one of 59 major-league “bonus babies” signed from 1953 through 1957, the bonus rule then in effect had its downside. The rule, initiated in 1947, rescinded in 1952, then revised and restored in 1953, required that any player signed for $4,000 or more had to be retained on the team’s major-league roster for two calendar years or be subject to the postseason draft. The rule made it difficult, if not impossible, for a player to get enough experience to succeed in the majors.

Gerald Donald Kindall, the son of Harold “Butch” Kindall and Alfield Kindall, wasn’t looking for instant gratification. He was just coming off a College World Series championship and had a basketball scholarship at the University of Minnesota, but he did want to see how he would fare in professional baseball, and the bonus money, reported to be $50,000, was extremely appealing in light of his family’s financial situation.

“My dad was working two jobs, 70 hours a week. My mom was in a wheelchair, I had two younger brothers, and my grandfather was living with us,” Kindall said in a telephone conversation. “It was a handsome offer so I signed, but not before I made a promise to my parents that I would complete my education.” True to his word, Kindall went back to school during the offseasons, completing his bachelor’s degree early in his big-league career and then pursuing and completing his master’s degree.

Kindall signed on June, 30, 1956, and the next morning was on a plane to Chicago, where the Cubs were completing a homestand. The Cubs had one other bonus baby, Don Kaiser, and a couple of weeks later signed a third, Moe Drabowsky. All three were required to be on the 25-man roster. Some of the older players who had struggled their way up to the majors and were paid poorly in the minors were resentful of youngsters coming in with a pocketful of money and taking a major-league spot.

“So, here I come walking in, a college guy and All-American with what they think is a pocketful of money. … They didn’t know I left that money at home,” Kindall said. “And what I didn’t realize was that to make room for me, they had to send down a popular utility player, Ed Winceniak, who was a real nice guy.”

Kindall was limited to pinch-running opportunities for several weeks, one of them leading to his first at-bat in Pittsburgh, against Elroy Face. He entered the game as a pinch-runner, scored, and returned to the dugout. Oblivious to the fact that the Cubs had batted around, he was shaken out of his reverie when someone hollered, “Hey kid, get a bat, you’re up.” He quickly grabbed a bat, rushed to the on-deck circle, and took a couple of rapid swings before stepping to the plate.

“Someone told me before I went up to watch for his forkball,” Kindall said lightly. “So I went up looking for the forkball, but he threw three fastballs. I watched two pitches and swung at the third for strike three.”

The 6-foot-2, 175-pound infielder, nicknamed Slim, made his first start, at shortstop, when Ernie Banks was sidelined by an infected hand, and he remained in the lineup for a couple of weeks. Kindall didn’t hit well but made enough defensive plays to validate Chicago’s substantial investment. Overall in 1956, he played in 32 games, hitting a scant .164 but making only four errors in 90 chances. In 1957 he played in 72 games and started 36, again struggling offensively and making 15 errors in 197 chances.

Although Kindall was an excellent hitter in college ball — he batted .381 with 18 home runs and 48 runs batted in as a senior — he struggled offensively in his first two seasons in the big leagues, hitting .164 and .160 in limited duty.

Whatever hardships were imposed by his premature inaugural, Kindall coped with them through his devout Christian beliefs and the friendship and guidance of several men, including Pepper Martin, the former Cardinals great and then the Cubs’ third-base coach, who took him under his wing on road trips. The Cubs management was impressed by Kindall’s glove and after the 1957 season, when the bonus rule was changed to read that a season and any part of another season counted as two, they sent their promising bonus baby to Fort Worth, hopeful that full-time duty would enhance his batting skills.

“I was grateful for the major-league experience, but I was glad when they sent me down,” Kindall said of his two seasons in Fort Worth. “That was my apprenticeship. It was an excellent experience, although it did come a year and a half late.”

Kindall played second base and hit .229 in 1958 with 16 home runs and 65 RBIs in 1958, when Fort Worth played in the Double-A Texas League. Fort Worth joined the Triple-A American Association in 1959, and Kindall went along. He slipped in home runs (7) and RBIs (42), but his 1960 spring training was impressive enough to earn him a return to the Cubs.

“I got a lot of help from the manager, Lou Klein, a former major-league infielder who was among those players who had jumped to the Mexican League in the 1940s,” Kindall said. “I played almost every inning with him while I was in Fort Worth.”

Kindall frequently started at second base in the next two seasons. He had exceptional defensive skills and range and occasionally hit for power but was unable to sustain any overall offensive consistency. Lou Boudreau, who in 1960 replaced Charlie Grimm as the Cubs manager, worked with Kindall, attempting to make him a slap hitter by getting him to abandon his long stride and uppercut swing, but even a Hall of Famer’s attention failed to get the promising big-league infielder on track offensively. Kindall was hitting .303 in early July of 1960 and hovered around .275 in mid-July of 1961, but each season he faltered late and finished at .240 and 242, respectively. Before heading back to Minnesota after the 1961 season, however, he got a vote of confidence when the Cubs informed him that Ernie Banks might be moved to first base and that he was the heir apparent at shortstop.

Kindall was ecstatic and had reason for greater optimism when he read an article in The Sporting News with the headline, “Banks to First Base, Kindall to Short.” When he completed a graduate class, he rushed home to tell his wife, Georgia, who had news for her husband. “She told me, ‘Gabe Paul called from Cleveland, and here’s the number, he wants you to call him back.’” Paul was the Indians’ general manager.

“I called him and was told that I had been traded to Cleveland.” The Cubs did move Banks to first, but André Rodgers became Chicago’s regular shortstop and Ken Hubbs, impressive in late 1961, took charge at second base.

Cleveland, however, quickly made Kindall feel at home and made him the regular second baseman. He started 154 of the team’s 162 games. He made nearly all the defensive plays and demonstrated some offensive promise, hitting as high as .289 on May 11. In what Kindall called his finest hour offensively, he played an integral role in a four-game sweep of the New York Yankees in June, a surge that hoisted the Indians into the American League lead. Kindall went 8-for-14 with two home runs, the first a two-run blast in the bottom of the ninth for a 10-9 victory and the second coming in the first game of a Sunday doubleheader played before nearly 71,000 frenzied fans in Municipal Stadium.

“I was living on a cloud,” said Kindall, “but the next day Boston came to town and I came back to ground in a hurry. I went 0-for-4.”

He struggled after this and finished the season with a lackluster .232 batting average, albeit an average underscored by 13 home runs and 55 RBIs. But despite further offensive advice from the Indians coaching staff, he continued to struggle at the plate. “I was a project every season,” Kindall said. “It was always, ‘If we could get Kindall to hit .260, he could be a regular.’ Maybe I got confused trying so many different things, and I struck out too much to hit for average.”

Besides his outburst against the Yanks, Kindall’s other claim to fame with the bat was his success against future Hall of Fame right-hander Robin Roberts, against whom he hit .269 and stroked four homers, the most he hit off any pitcher. “One time (Roberts) said, ‘Hey kid, how do you hit so well against me?’” Kindall said. “I told him at first that I didn’t know but then explained that he gave me good fastballs below the belt. From that point on I got nothing but belt-high fastballs and curves. I don’t know why I said that.”

Kindall started more than half of Cleveland’s games in 1963, switching between shortstop and second base, and the lanky infielder once again had another season of good-field, no-hit, finishing with a .205 average. So when manager Birdie Tebbetts had a heart attack in early April of 1964, Indians interim manager George Strickland and Gabe Paul had a different plan. Larry Brown became the starting second baseman, with Kindall catching an occasional start until he was sent to Minnesota in a three-way deal on June 11, just before the trading deadline.

At Minnesota it became a case of “Who’s on second?” with Kindall sharing the job with more than a half-dozen other infielders. Kindall played in 85 games in 1964, 41 as a starter, and occasionally filled in for Zoilo Versalles at shortstop, but once again he was unable to hit and between the Indians and Twins, he batted .183. He did, however, survive the next spring training and wound up playing in 125 games (102 starts).

In late June of 1965, Kindall tore a muscle just above his hamstring, missed more than a week, and, shortly after getting back in the lineup, reinjured the muscle while running out a base hit down the line. Frank Quilici, a 26-year-old rookie and, like Kindall, a former All-American shortstop, was called up from the minors in July and shared time with Kindall at second. Although Kindall started more than 100 games during the regular season, Quilici played every inning in the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“It was a disappointment, but while I was healthy in time for the World Series, Quilici was doing such a good job there was no reason to take him out,” Kindall said. “There is one thing that rankles me to this day and that was an article written in the [Minneapolis] Tribune. A reporter said that I had never gotten a hit off Sandy Koufax [who pitched three games in the Series], but that wasn’t true.

“I faced Koufax at least 30 times while I was in the National League and I confess that I struck out most of the time, but I did have at least four hits against him. But I think that maybe affected [manager Sam Mele’s] thinking. I’d grab a bat and walk around hoping he’d see me, but that didn’t work.” Actually, Kindall had more trouble than he thought against Koufax: 28 at-bats, 2 singles, 1 walk, and 18 strikeouts.

When the Twins broke camp after spring training in 1966, Kindall was beckoned to owner Calvin Griffith’s trailer and told he was being released, that he still might have time to catch on with another team. “Cal, never one known for his diplomacy, told me, ‘I’ve got you and Quilici, and neither one of you can hit,’” Kindall said, laughing. “‘So, I’m giving you a chance to make a deal for yourself.’ I was shocked and surprised. I know my leg was bothering me and that I hadn’t played well in exhibition games. After the injury I couldn’t cover the ground I did before.

“But I figured I’d done some important things for the Twins. He did ask me if I’d go to the minors, but I told him that I wouldn’t.”

So Kindall cleaned out his locker, joined the recently traded Dick Stigman, who had been dealt to the Boston Red Sox, and went back to their spring quarters to wait for their wives, who had taken their children to the zoo. Kindall did check with several teams to see if they had an opening, but when he realized that all the rosters were set, he began looking for a job. Fortunately, he had a great reputation with the University of Minnesota, and athletic director Marsh Ryman patched a job together for him, one that included assisting in baseball and basketball, directing a fundraising program, and selling advertisements for the football program.

Eventually Kindall settled into a full-time assistant’s job on the baseball team with his former coach, Dick Siebert, and in February of 1972 became the University of Arizona’s head baseball coach in waiting (taking over the position the following year).

Life was good until 1984, when Georgia, a registered nurse, was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease; she died on June 29, 1987. “I had been teaching and coaching at the time, but the university relieved me of my teaching duties,” Kindall said. “It wasn’t baseball that helped me get through it, it was my faith in the Lord, but I continued to coach. Georgia insisted that I keep coaching.”

In July of 1988 Kindall met Diane, a widow, and they became engaged in September. They were married on Thanksgiving weekend. Kindall continued to coach until he retired in 1996 after having won 861 games and three College World Series titles. As of 2014 he was the only man ever to have played on and coached College World Series championship teams, and in an ironic twist, the man with a .213 major-league batting average was the only player ever to have hit for the cycle in the College World Series.

The disappointing conclusion to Kindall’s professional playing career also didn’t diminish his appreciation for the major-league opportunity; in fact, he credited the experience for opening the door to arguably the greatest phase of baseball life. “If I had any success as a college coach, it’s because of the many good things I saw and learned in professional baseball … the struggles it presented,” Kindall said. “As spotty as my career was, it opened the door for me to get the best college coaching job in the world. There were three men interviewed for the job [at Arizona], Bobby Richardson, Steve Hamilton, and me.

“Bobby withdrew and so they asked him if he would recommend one of us. He said, ‘Jerry Kindall is a close friend and Steve Hamilton named his son, Robert, after me. I don’t know what to tell you.’ I really think they wound up flipping a coin.”

Kindall’s atypical power for an infielder raised this question: Did he ever consider that playing the outfield might have enhanced his major-league career? He responded instantly and emphatically. “No, I belonged in the infield … as a middle infielder,” he said. “Others may have considered the possibility, but I never did.”

It goes without saying that Jerry Kindall also belonged in baseball from the day he entered St. Paul’s Washington High School, where he was named the 1953 State High School Baseball Tournament’s Most Valuable Player, until the day he retired from Arizona.

He died at the age of 82 on December 24, 2017, after suffering a stroke three days earlier.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “A Pennant for the Twin Cities: The 1965 Minnesota Twins” (SABR, 2015), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. It originally appeared in “Minnesotans in Baseball” (Nodin Press, 2009), edited by Stew Thornley.

Sources

The Baseball Encyclopedia, the Baseball Cube and several other Google sites to validate Baseball Cube information, Baseball Old- Timers Data Base, the University of Minnesota Media Relations department, the University of Arizona database, Wikipedia, and more than two hours interviewing Kindall by telephone

Full Name

Gerald Donald Kindall

Born

May 27, 1935 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

Died

December 24, 2017 at Tucson, AZ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.