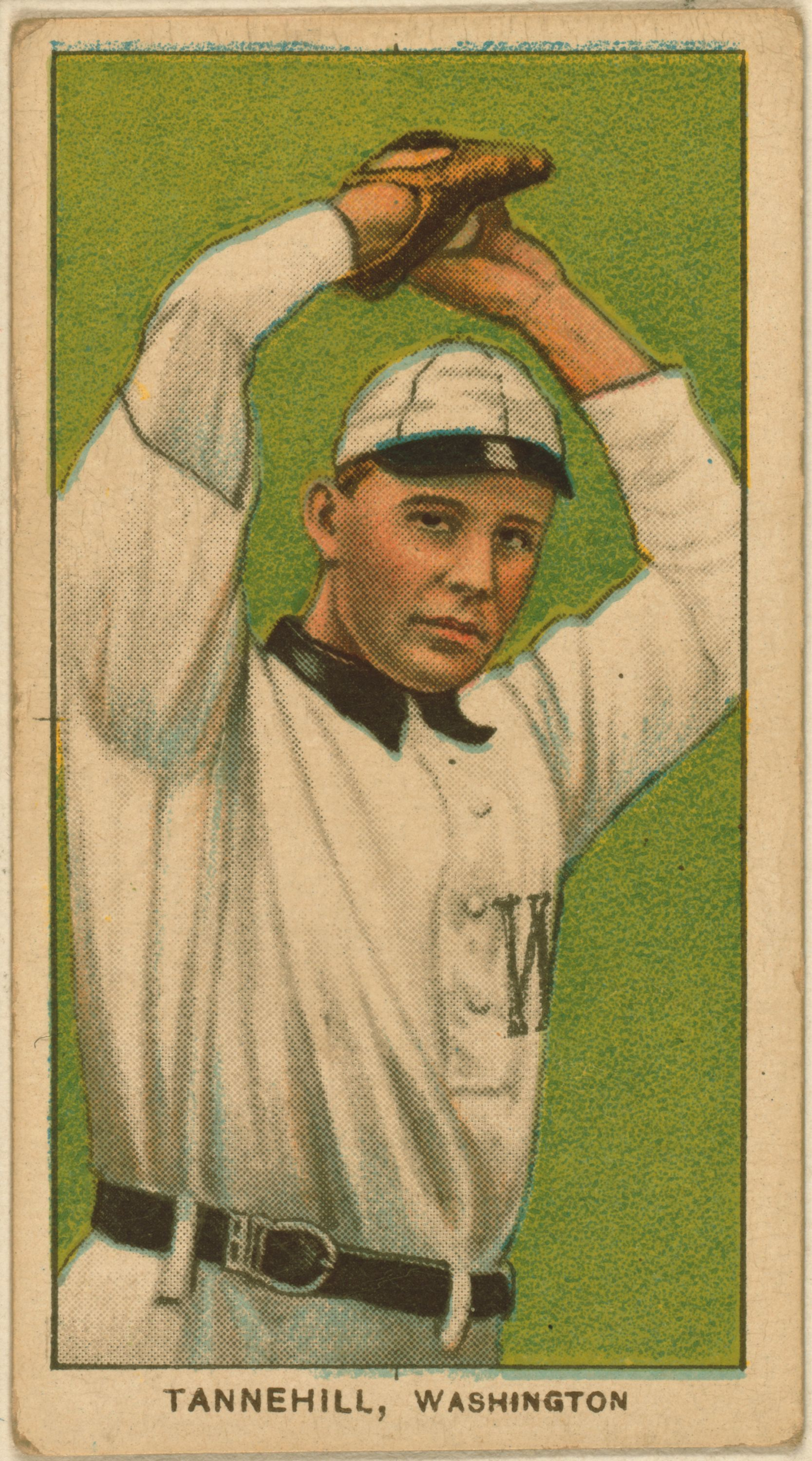

Jesse Tannehill

He stood only 5’8″ and weighed just 150 lbs., but Jesse Tannehill was one of the most versatile players during the Deadball Era. Not only did the black-haired left-hander compile a 197-117 lifetime record and 2.80 ERA, the switch-hitter also played in the outfield 87 times and pinch hit in 57 games. A former saloon owner and a superstitious player who wouldn’t shave on days he pitched, Tannehill had outstanding control and used his slow curve to routinely strike out twice as many as he walked, though he never did either with regularity and opted to let his defense make plays behind him. “I think Tannehill the greatest of living pitchers for the good reason that he was never rattled in his life,” said his former minor league manager, Jake Wells. “No matter how hard his delivery may be, he never loses his head. I like a pitcher who can take punishment and pull himself together at a critical moment. Then don’t forget that Tannehill is a good batsman.”

He stood only 5’8″ and weighed just 150 lbs., but Jesse Tannehill was one of the most versatile players during the Deadball Era. Not only did the black-haired left-hander compile a 197-117 lifetime record and 2.80 ERA, the switch-hitter also played in the outfield 87 times and pinch hit in 57 games. A former saloon owner and a superstitious player who wouldn’t shave on days he pitched, Tannehill had outstanding control and used his slow curve to routinely strike out twice as many as he walked, though he never did either with regularity and opted to let his defense make plays behind him. “I think Tannehill the greatest of living pitchers for the good reason that he was never rattled in his life,” said his former minor league manager, Jake Wells. “No matter how hard his delivery may be, he never loses his head. I like a pitcher who can take punishment and pull himself together at a critical moment. Then don’t forget that Tannehill is a good batsman.”

Tannehill was proud of his hitting ability and boasted a lifetime average of .256, including a .336 mark in 1900. Tannehill also enjoyed capitalizing on his speed. For many years he bragged that he was one of the few pitchers to ever steal home. “Tannehill has everything that goes to make up a good fielder, being very speedy, a sure fly catch, a throwing arm that cannot be exceeded by anyone,” wrote The Sporting News. “Add to this the fact that he is a splendid batter and base runner and what more could be wanted.”

Jesse Niles Tannehill was born on July 14, 1874, in Dayton, Kentucky, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. Tannehill was the middle child of William, a ship carpenter, and Julia Tannehill. Baseball was in the family genes. His father played for the Eagles of Dayton in the 1860s, one of the founding baseball clubs in the Cincinnati area, and Jesse’s younger brother, Lee, enjoyed a ten-year career as a White Sox infielder. Jesse’s baseball skills were first noticed on the Cincinnati sandlots, where Tannehill starred for the Cincinnati Shamrocks. The Cincinnati Reds signed Jesse and on June 17, 1894, he made his big league debut. Tannehill finished the season 1-1 in five games with a 7.14 ERA. The next two years he posted 22 and 27 win seasons for Richmond of the Virginia League and helped them capture consecutive league titles. At the close of the 1896 season Pittsburgh drafted him.

Tannehill went 9-9 in his first full season in the majors, while filling in regularly in the outfield. He excelled so well that the Pirates considered making him a full time outfielder, but by the start of the 1898 season Tannehill was designated as a utility outfielder and pitcher. It was a role that he carried with him throughout his career. Tannehill blossomed as a pitcher in 1898, winning a career high 25 games. The wins continued and in four of his final five seasons with the Pirates he won 20 or more games.

On the mound, the short left-hander relied on an agonizingly slow curveball and razor-sharp control. Every year from 1897 to 1904, Tannehill ranked among his league’s top five in fewest walks per nine innings pitched. He wasn’t a big strikeout pitcher, either–he recorded only 940 strikeouts in more than 2,750 career innings–but his low walk totals still ensured him an annual spot among pitchers with the best strikeout to walk ratios. In 1901, he fanned a career-high 118 batters while walking just 36, and led the National League with a 2.18 ERA as the Pirates captured the pennant. Pittsburgh’s dominance continued the following season as the Pirates won 103 games and clinched the pennant with a month left in the season. The Pirates’ staff (Deacon Phillippe, Tannehill, Sam Leever, Ed Doheny, and Jack Chesbro) threw twenty-one shutouts, led the league in strikeouts, walked the fewest batters, and threw back-to-back two-hitters and back-to-back three-hitters.

Amidst Pittsburgh’s success, rumors surfaced about players secretly negotiating with Ban Johnson to join the American League, with Tannehill believed to be one of the main catalysts. After a game in August, Jesse got into an altercation with reserve Jimmy Burke. A scuffle occurred resulting in Tannehill dislocating his pitching shoulder. Tannehill went to a local hospital where the doctors administrated ether so his arm could be popped back into place. While under the anesthetic Tannehill told Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss about conversations he had with Johnson. He even dropped the names of the other Pirates involved. Five days later at Tannehill’s apartment, six Pirates were promised a $1,000 bonus for jumping leagues in 1903. Word got out and suspected ring-leader Jack O’Connor was suspended even though Tannehill reportedly told a friend that he was behind the meeting. When an All-Star game was set up after the season between the Pirates and a group of American League All-Stars, Tannehill did not participate. Dreyfuss, knowing Tannehill had already received a bonus from the American League, handed the pitcher his unconditional release and told him to take his baggage from Exposition Park at once. Along with teammates O’Connor and Jack Chesbro, Tannehill signed with the New York Highlanders.

Jesse’s 1903 season was an unpleasant one, as the pitcher posted a mediocre 15-15 mark and clashed with manager Clark Griffith over the latter’s suspension of O’Connor. Tannehill also complained that his struggles were the result of pitching at Hilltop Park. “The grounds are on a high bluff overlooking the river and the cold wind blows over the diamond morning, noon and night,” said Tannehill. “A man would have to have a cast iron arm to pitch winning ball under these circumstances.” His poor pitching was more likely the result of an arm problem that he suffered during the season. It was an injury that would nag him for the rest of his career, and prevent him from handling heavy workloads. Unhappy in New York, after the season Tannehill expressed interest in joining his hometown Cincinnati Reds. Instead the Highlanders traded the unhappy hurler to the Boston Americans for pitcher Tom Hughes.

Critics questioned the trade, arguing that the sore-armed Tannehill was in decline. Hughes was four years younger than Jesse and had won 20 games for Boston in 1903. Nonetheless, Boston manager Jimmy Collins assured critics that Hughes would not be missed. “I am more pleased than ever with my trade for Tannehill,” stated Collins. “We need a left-hander and I don’t know a better one in the business. He is in great shape and will be Johnny-on-the-spot with that stick of his and that helps a team wonderfully, I tell you.” Collins was right–the trade proved to be a winner for Boston. Tannehill went 21-11 with a 2.04 ERA in 1904 while Hughes struggled to a 7-11 mark before New York traded him in midseason. Boston, powered by a stalwart pitching rotation which established still-standing American League records for complete games (148) and fewest walks (233), won a second consecutive American League pennant. On August 17, Tannehill pitched the third no-hitter in American League history when he blanked the White Sox, 6-0.

As it turned out, all the complete games wore on the veteran pitching staff, and Boston sank quickly in the standings. In 1905, the Americans finished a disappointing fourth, as Tannehill was the only starting pitcher to post a winning record (22-9). The following year, the Americans endured a 20-game losing streak on their way to a last-place finish, and Tannehill posted a mediocre 3.16 ERA, finishing the year with 13 wins and 11 losses. It was the only winning record on the team, though it would also be the last winning season of his career.

A sore arm limited Tannehill to just six wins the following season and after pitching in one game in 1908, he was traded to Washington. Boston management had become unhappy with him. On numerous occasions Tannehill mentioned that he would rather play in Washington for his hunting companion Joe Cantillon than anywhere else. Once Tannehill arrived in the nation’s capital he wasn’t shy about his happiness in leaving Boston. “I could not pitch in Boston. The weather there is hard on my arm and I could not get it going right,” stated Tannehill. “It feels better already, though I have only been out of the town for a few hours.” Despite the change in climate, Tannehill was unable to stay healthy for the Nationals, as a dislocated shoulder and displaced ribs limited him to two wins in 1908. The next season Tannehill pitched in only three games before being sold to Minneapolis of the American Association.

Offended by the pay cut and still bothered by recurring arm troubles, Jesse refused to report; instead he returned to Dayton and played for some local teams. Tannehill eventually joined the Millers when Cantillon was named manager in 1910, but once again his arm went back on him and he was given his unconditional release after pitching in eight games. Tannehill signed a contract to play for Cincinnati in 1911, but his major league return was short-lived. While Cincinnati suffered its worst opening day loss, 14-0 to the Pirates, Tannehill gave up six hits, seven runs (three earned), and walked three in four innings of mop-up work. After the game Jesse asked manager Clark Griffith for his release. He never played again in the major leagues. Tannehill returned to the minor leagues later that season, playing in the Southern Association, first for Birmingham and later Montgomery.

In 1912, Tannehill signed on as an outfielder for South Bend of the Central League. Despite batting .285 in 59 games, Tannehill was given his unconditional release. Newspaper reports stated he was promoting discord on the team. He later played for Chillicothe (Ohio State League) and St. Joseph (Western League) before ending his playing career.

Following his retirement as an active player, Tannehill remained close to the game, piloting Portsmouth of the Virginia League in 1914. After stints as an umpire in the Ohio State, International and Western Leagues, Tannehill returned to the majors as a coach for the Phillies in 1920, lasting only one season. In 1923 Jesse took the managerial reins one last time for Topeka in the Southwestern League.

In his later years, Jesse worked in a Cincinnati machine shop and was a frequent visitor to Crosley Field. Tannehill died from a stroke at Speers Hospital in Dayton on September 22, 1956. Survived by his wife, the former Beulah Anderson, he was buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Southgate, Kentucky. The couple left behind no children.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Browning, Reed. Cy Young: A Baseball Life. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

DeValeria, Dennis and Jeanne DeValeria. Honus Wagner: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996.

Thorn, John, Peter Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza. Total Baseball. New York: Viking, 1997.

National Baseball Library

Society for American Baseball Research

Chicago Tribune

Kentucky Post

Kentucky Times Star

Los Angeles Times

New York Times

Sporting News

Washington Post

Full Name

Jesse Niles Tannehill

Born

July 14, 1874 at Dayton, KY (USA)

Died

September 22, 1956 at Dayton, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.