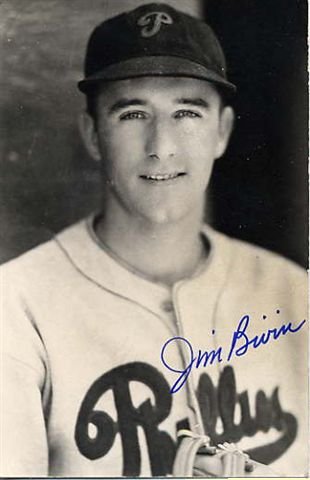

Jim Bivin

Jim Bivin’s career in the major leagues was undistinguished. He pitched a single year in the majors for the 1935 Philadelphia Phillies, posting a 2-9 record with a 5.79 ERA. Bivin’s play for the Phillies would rest easily in obscurity except for the fact that he brushed up against baseball immortality. In one of his appearances, Bivin induced Babe Ruth to ground out, the only time he would face the slugger. It turned out to be Ruth’s last major league at bat, an occurrence that would forever define Bivin’s career.

Jim Bivin’s career in the major leagues was undistinguished. He pitched a single year in the majors for the 1935 Philadelphia Phillies, posting a 2-9 record with a 5.79 ERA. Bivin’s play for the Phillies would rest easily in obscurity except for the fact that he brushed up against baseball immortality. In one of his appearances, Bivin induced Babe Ruth to ground out, the only time he would face the slugger. It turned out to be Ruth’s last major league at bat, an occurrence that would forever define Bivin’s career.

James Nathaniel Bivin Jr. was born to Frances and James Sr. on December 11, 1909, in Jackson, Mississippi, where the elder Bivin was employed as a millwright. James Junior, an only child, passed his youth playing ball during the hot Mississippi summers on local sandlots. In 1925 he began attending school at Agricultural High in Benton where he studied arithmetic, grammar, became acquainted with the rudiments of farming and continued to play baseball.

His skills improved to the point that in 1929 when the New York Giants sent their second team through the area and played a game against the Jackson Senators of the Cotton States League in an exhibition game, he was asked to pitch. Bivin allowed only one run impressing player manager Walter Holke of the Quincy Indians of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three I) League. Holke promptly arranged to sign Bivin to a contract at the tail end of the season.

The ink on the contract was scarcely dry when Bivin’s services were transferred to the Davenport Blue Sox of the Mississippi Valley League. Bivin posted a solid 12-10 record for the season. Next year he moved up to the Class Wichita Aviators of the Western League and compiled a 14-9 performance. In 1932 he became part of the Pittsburgh Pirate affiliated Tulsa Oilers, also in the Western League. Bivin’s 15-7 effort helped Tulsa capture the pennant that year.

Sticking with Tulsa, which transferred its allegiance to the Texas League the following year, Bivin posted a lackluster 11-13 performance. All was not lost however as he married his sweetheart, Hilda Stringer on August 22, 1933.

He began 1934 with Tulsa, but shortly into the season after having held the Galveston Buccaneers to just three hits, they traded pitcher Merritt Hubbell and cash for Bivin’s services. Bivin paid immediate dividends leading the Bucs with a 20-14 record for the year with 149 strikeouts in 281 innings. Playing with the likes of future major leaguers Beau Bell, Harry Gumbert and Wally Moses the Bucs won the Texas League championship.

Toward the end of the season, the Philadelphia Phillies purchased Bivin from Galveston. “Slim” (6’1” 160 pounds) Jim, as he was now nicknamed, was to report to Philadelphia for 1935. He would be joining a team that had finished seventh the previous two years; his addition to the Phillie pitching staff was a welcome addition. The April 4, 1935, issue of The Sporting News contained an article describing Phillie Manager Jimmie Wilson’s faith in his new pitching prospect.

That faith would be put to the test in the first game of the season. Down 6-3 against the Brooklyn Dodgers in the top of the sixth inning, at Baker Bowl, he let two inherited runners score. Finishing the game, he allowed four more runners to cross the plate, only one of which was earned as Brooklyn went on to demolish Philadelphia 12 to 3. Over the next several weeks, he relieved and made spot starts. On May 24, he made history of sorts by appearing in the first night game in major league history. President Franklin Roosevelt pressed a button at the White House lighting up Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. The game was a pitcher’s duel with Reds ace Paul Derringer besting Phillie Bob Bowman 2 to 1. Bivin came on in relief of Bowman in the bottom of the eighth setting the Reds down in order.

While pitching in the first major league night game granted a degree of distinction, less than a week later his appearance against the Boston Braves permanently etched his name into the lore of baseball. On May 30, the Braves played Philadelphia at Baker Bowl. Philadelphia was in familiar territory, seventh place, Boston in the cellar on their way to a horrific 38-115 record. A crowd of 15,122 fans showed up to watch a doubleheader between two teams going nowhere, lured in part by “Babe Ruth Day” honoring the 40-year-old Ruth who had been purchased from the New York Yankees by Boston during the off-season, principally as a gate lure. By then Ruth’s skills had seriously deteriorated. Despite having hit three home runs in Pittsburgh several days earlier, Ruth was hitting under .200, frequently missing games because of injuries.

Starting the opening game of the doubleheader, Bivin faced Ruth in the top of the first inning inducing him to hit a weak roller to first baseman Dolph Camilli. In the bottom of the inning, chasing after a hit, Ruth took a tumble and reinjuring a sore knee removed himself from the game. No one at Baker Bowl could have guessed this was his last major league game, which became official when he announced his permanent retirement as a player on June 2, 1935. For Ruth this was the end of a storied career; Bivin would henceforth be recalled, first and foremost for having faced Ruth in his last major league at bat.

At this point Bivin was 0-3 with a 3.69 ERA. He continued to make occasional starts as well as relieve. On July 16 at Wrigley Field, Bivin came on to relieve in the bottom of the sixth as the Cubs threatened to tie the score. Bivin held them to one run through the rest of the game to gain his first major league victory. A little over a month later on August 21 at Baker Bowl, Bivin won his second game, also against the Cubs. His record at that point was 2-6. On September 29 in the second game of a doubleheader and last game of the season he was called on to relive against the Brooklyn Dodgers with the score tied 4-4 in the bottom of the 8th inning. Bivin held the Dodgers scoreless. With that, the game was called because of impending darkness. Jim Bivin had just pitched his last major league game.

Those two wins against the Cubs were his only two major league wins as he finished the season 2-9 with a 5.79 ERA. Particularly telling was that over 161 innings he surrendered 220 hits; his control was suspect as he generated 65 bases on balls as opposed to 54 strikeouts for the Phillies who finished in seventh place. That he allowed 20 home runs, second in the league, did nothing for his record.

On November 17, Bivin was traded to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League for then minor league catcher Bill Atwood. Over the winter, Bivin found employment working on a cargo ship. When Bivin reported to the Orioles training camp, he was eighteen pounds lighter, blaming his weight loss on the undesirable cuisine provided sailors.

Oriole’s manager Guy Sturdy told reporters during spring training his faith in the Orioles pitching staff, including Bivin was higher than he had for the prior year’s mound corps. Bivin, renewing his minor league career, one that extended through 1949, went 8-8 for the Orioles in 1936. After starting with the Orioles in 1937, he was traded back to Galveston midseason. While with the Buccaneers he fashioned a seven-inning no-hitter against the San Antonio Missions on August 3, 1937. His travels through the minors continued in 1938 as he, along with Orville Armbrust and Junie “Lefty” Barnes was traded to the Shreveport Sports. Interestingly enough, Armbrust also had a claim to baseball immortality through a connection to Ruth. Pitching for the Washington Senators in 1934, he started the last game of the season against the New York Yankees and won his only major league victory that marked the last game Ruth appeared in Yankee.

While with Shreveport, Bivin did solid work for manager Claude Jonnard, leading the staff with 15 victories for the sixth place Sports. Nineteen thirty-nine saw another mid-season trade, this time to the Oklahoma Indians. For the season, he was a combined 12-17. Next season he began with the Knoxville Smokies of the Southern Association, a farm team of the New York Giants.

His stay with the Smokies was short lived, as he was once again traded midseason, this time to the Richmond Colts of the Piedmont League. Bivin had played at various A level classifications since returning to the minors in 1936, however this trade to the Colts marked a demotion to B League play. Here, Bivin found a degree of success. On June 19, 1940, he threw a no-hitter against the Durham Bulls. In 1941, he won 20 games for the Colts, leading the league in wins.

Bivin started the 1942 season with Richmond, but the advent of World War II would soon interrupt his career. In early May, he received word from the draft board in Raymond, Massachusetts that he was eligible for the draft. Just over two months after receiving notice, Bivin was inducted into the Unites States Marine Corp, exchanging his baseball cap for a garrison cap. He finished the season 12-9 for Richmond with a 2.54 ERA.

Richmond held a “Jim Bivin Day” at Mooers Field before he left to serve. The popular pitcher received a monetary gift of $114.68 as a going away present from the fans. Then he was off to serve, and except for an emergency trip home to see his seriously ill mother in October 1942, he participated in various training efforts to prepare for offensive maneuvers in the Pacific.

While many ballplayer draftees found themselves on various service teams to entertain the troops, their number did not include Bivin, who found himself participating in the Battle of Tarawa. Tarawa, located in the Gilbert Islands was the first instance of serious Japanese resistance to the United States efforts to expand the range of their offensive capacity. The Second Marine Division spearheaded the amphibious attack, which was one of the first of its kind. It featured the first usage of LVT’s (Landing Vehicle Tracked), brought in to navigate over the jagged coral reefs surrounding the island. The main battle, which began on November 20, 1943 and lasted four days, claimed over one thousand Marines and more than four thousand Japanese during the fierce fighting that ensued. In the January 6, 1944, issue of The Sporting News Bivin, who participated in the invasion, shared, “Those machine gun bullets whizzed by us a heck of a lot faster than the line drives I used to duck in the pitcher’s box. And you can at least see a line drive most of the time.”

After the battle, the Second Division regrouped in Guam. There, Bivin pitched for the local Marine team before his unit was sent out to Saipan in June 1944 and Iwo Jima in February 1945. At war’s end, Bivin received an honorable discharge, having earned a Purple Heart and two Bronze Stars. Fellow service members knew him as “Gentleman Jim” for his respectful demeanor, a descriptive based on the then popular Warner Brothers film, Gentleman Jim released in 1942 and starring Errol Flynn.

Bivin returned to the Colts in 1946 where the 38-year-old right-hander posted a 6-10 record. The following season, Bivin moved back to his home state of Mississippi where he assumed pitching and management duties for the Class C Greenwood Dodgers of the Cotton States League. There he coached, among others, Ray Moore future major league pitcher with the Baltimore Orioles, Chicago White Sox, and Washington Senators (later Twins). While Moore won 18 games, Bivin made occasional forays onto the mound ending with a 10-3 record and a 2.60 ERA.

Greenwood won the league championship in 1947, then in the post season playoffs bested the Clarksdale Planters three of four games before defeating the Greenville Bucks in seven games of the final playoff series. While winning the championship, the Dodgers path toward it was not without controversy.

Toward the end of the season, Bivin found himself involved in a legal matter precipitated by one of his ballplayers. On August 12, Bivin’s starting pitcher, Peter Zmitrovich faced the Helena Seaporters in the first game of a doubleheader at Helena’s Recreation Park. After a rally against Zmitrovich caused him to be taken out of the game, he made an obscene gesture toward the stands, setting off a brawl involving players and fans, one of whom entered the dugout and confronted Zmitrovich. The situation only came under control when local police calmed the situation. Helena’s sheriff sent for Zmitrovich and Bivin, who, faced with a tense situation, fined his errant pitcher $25 for his disrespectful behavior and promptly sent him back to Greenwood. Cotton League President, Jim Griffin went a step further, suspending Zmitrovich indefinitely after receiving a report on the incident. Faced with the threat of continued legal action by Helena officials, Zmitrovich was transferred to the Abilene Blue Sox in the West Texas-New Mexico League, presumably to remove him from further legal action.

Bivin managed Greenwood for three seasons, each year the Dodgers making the playoffs. Each year he pitched several games. His final appearances on the mound came during the 1949 season. He posted a 4-2 record and a 2.70 ERA. During his minor league career, Bivin went 163-133 with a 3.36 ERA.

His solid performance at Greenwood over three seasons earned him a promotion to the Danville Dodgers of the Three-I League. The Class B Dodgers finished second which earned Bivin further promotion to the Class A Pueblo Dodgers in the Western League. There he coached several future major leaguers including Elroy Face, Bob Lillis and Ron Negray. While managing at Pueblo, the Bivin family decided to settle there after years of shuffling around the minor leagues. It was time to put roots down.

While the family settled in Pueblo, Bivin took on one more managerial assignment, this time the Lancaster Roses of Lancaster, Pennsylvania in the Interstate League. There, Bivin led the team to a 75-65 record to close out a career that began 20 years earlier. Perhaps he knew it was time to quit when he was thrown out of a game against the York, Pennsylvania White Roses in June. His ejection occurred after arguing too loudly on a play – it was the first (and last) time in his career.

Bivin decided it was time to quit the game. Years later, Florida sportswriter Jack Hairston explained Bivin’s decision in an article for the Lakeland Ledger, titled “Friends Not Making It Is A Little Saddening”:

“Bivin started as a manager in the Class C, and in three years he won three pennants. Moving up to Class B for one year, he finished second. Then he moved up to Pueblo of the Class A Western League. The first season he gave Pueblo a first division team for the first time in years. The second year he finished in the second division and was fired. He could hardly be blamed if he wondered what it took to find steady employment in baseball. He had been working in the off-season as a nurse at the state mental hospital, and the job paid as much as he was making managing in the bus leagues, and the nurse job was more secure. Bivin bade baseball farewell, and it was the nursing professions gain, baseball’s loss.”

Bivin, no longer wishing to earn his living as a baseball vagabond, earned certification as a medical nurse and gained employment with the Colorado Institute of Mental Health in Pueblo. He continued working as a nurse until retirement. Hilda passed away on December 31, 1970, after thirty-seven years of marriage. Surviving Hilda nearly twelve years, Bivin died on November 7, 1982, after a series of heart attacks. Burial was at Imperial Memorial Gardens, where Hilda was interred. Bivin’s children, James Jr. and Janice as well as two grandchildren survived him.

Bivin’s major league career was brief, just one year in the big leagues. For having pitched to one batter in a meaningless game, he became part of baseball’s lore. Twelve years after his passing, Bivin realized major league recognition of a different sort. In 1994, The Sporting News endorsed a baseball card set that featured the work of famed baseball photographer Charles M. Conlon. The series was titled “The Conlon Collection.” Bivin was #1299 in the set proudly wearing his Philadelphia uniform at the age of 25. His career spanned 20 seasons, interrupted by serving in the defense of his country. His upward advancement through the Dodger farm system reflected well on his managerial abilities, his later nickname as “Gentleman Jim” reflected highly on his character. Each of these accomplishments, certainly more substantial than having made Babe Ruth ground out in his last major league at-bat.

Sources

Harrison, Daniel W. and Scott P. Mayer, Baseball And Richmond: A History Of The Professional Game 1884-2000 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003).

McCombs Wayne, Baseball in Tulsa (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

Simmons, Edwin Howard and J. Robert Moskin, The Marines (Fairfield, CT: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates Inc., 1998).

Wescott, Rich & Frank Bilovsky, The Phillies Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004).

Hope Star (Arkansas, 1947)

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (1932)

Pittsburgh Press (1932)

The Boston Globe (1935)

The Chieftain (Colorado 1982)

The Lakeland Ledger (Florida 1973)

The Sporting News (1933-1965)

Baseballguru.com

Baseballinwartime.com

Baseball Almanac

Baseball-Reference.com

Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Baseball Hall of Fame Museum

BaseballLibrary.com

Net54Baseball.net

Retrosheet.org

SABR Encyclopedia (SABR Members)

Roberta Allen and Jeanie Cooke – Danville Public Library, Danville, Illinois

Gary Bedingfield, Baseball In Wartime Website Author

Danielle R. Clifford, Research Assistance

The Charles M. Conlon Photography Collection

Sgt. Brian A. Russell, USMC Desert Storm

Chad S. Sullivan, Research Assistance

Tabitha Davis and Maria Tucker, Pueblo City-County Public Library District

The Baseball Hall of Fame Library and Museum, Cooperstown, New York

Full Name

James Nathaniel Bivin

Born

December 11, 1909 at Jackson, MS (USA)

Died

November 7, 1982 at Pueblo, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.