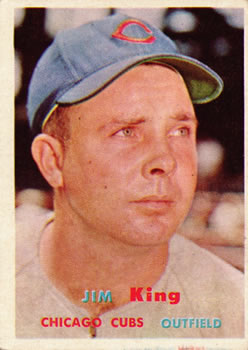

Jim King

Jim King started in left field for the San Francisco Giants in the first major-league game played in California. His best seasons, however, came after he was selected by the expansion Washington Senators, with whom he remained for 6½ years, longer than any of the other 27 players the team drafted in December 1960.

Jim King started in left field for the San Francisco Giants in the first major-league game played in California. His best seasons, however, came after he was selected by the expansion Washington Senators, with whom he remained for 6½ years, longer than any of the other 27 players the team drafted in December 1960.

King was a strong-armed, left-handed-batting, outfielder who hit with power. Although he never had more than 511 plate appearances in a season, he reached double figures in home runs eight times, topping out at 24 in 1963.

James Hubert King was born on August 27, 1932, in Elkins, Arkansas, the youngest son of Elmer and Mary Alice Lawson King.1 He was one of six brothers and two sisters.2 Before his death at age 82 on February 23, 2015, he was the last of his siblings still alive.3

When he was a teenager, King went to live with one of his older brothers. He dropped out before he reached high school. His talent as a baseball player was already evident as he had begun playing against older opponents by the time he was 14. Even then, his arm strength was recognized.4

In his mid-teens, he began playing American Legion baseball and for several highly skilled teams in Elkins and Wesley, Arkansas. He attracted the attention of Cardinals scout Fred Hawn, who persuaded the 17-year-old to play for Vernon, Texas, in the independent Class D Longhorn League.5

With the Vernon Dusters in 1950, King hit .302 with a dozen home runs in 144 games. That was good enough to earn him a contract offer from Hawn and the Cardinals, who assigned him to Winston-Salem in the Carolina League for 1951. There, the 18-year-old struggled in 18 games, hitting .213. Sent to Fresno in the Class C California League in May, he hit .333 in 116 games. He began the ’52 season with Omaha in the Class A Western League, but hit just .238 with one homer in 63 games, so was returned to Fresno on July 2. He hit .328 there in 59 games. He was named to league all-star teams at Vernon in ’50 and Fresno in ’51.6

Still just 20 years old, King was back at Omaha in 1953. This time, over a full season, he hit .280 with 10 homers. He hit his stride at Omaha the next season, hitting .314 with 25 homers and a team-record 127 runs batted in. King was a Western League all-star in ’54. He began displaying a talent that would help define his career: a rifle right throwing arm. He had 19 outfield assists against unwitting baserunners.7

On September 2, 1954, an Omaha television station gave away a reported 26,000 tickets to a pregame promotion that featured Joe DiMaggio and Dizzy Dean. The advance advertising said Dean would pitch to DiMaggio and Omaha’s King, but Dean, in street clothes, threw about 15 pitches just to the retired Yankee Clipper. None left the park, but DiMaggio did homer off a batting-practice pitcher. King had his photo taken with the two Hall of Famers and homered during the scheduled game, before an announced crowd of 18,284. However, many more people showed and eventually were all let in.8

Eight days later, on September 10, King reached on an error against Lincoln’s Orinthal Anderson, an outfielder making his second pitching appearance. King advanced on a bunt and a second error, then scored a groundout, the only run in what otherwise would have been a perfect game for Anderson. Instead, he tossed a no-hitter, but lost 1-0.9

King married the former Rose Bell, who was from Elkins, after the ’54 season. He and his wife, who survived him, had been married for 60 years when he died. They had a daughter, Sheree, born in 1955, and a son, David, who was born in 1958.10

King’s all-star performance in 1954 attracted the attention of Wid Matthews, the Cubs’ director of player personnel. On his recommendation, the Cubs selected King in the minor-league draft in November 1954 from the Cardinals’ Rochester (New York) Triple-A roster.11

Cubs manager Stan Hack mentioned King as one of six potential outfielders who could make the team in 1955, and that’s exactly what King did. As the season began, he was battling Ted Tappe for starts in right field. To get him in the lineup, the Cubs were reported to be considering trying King at third base, although he never appeared in a game there.12

King saw considerable playing time over his two seasons in Chicago, hitting .256 in 113 games and 333 plate appearances in ’55. He hit the first of his 11 homers at the Polo Grounds. He received far more votes for the All-Star team than Roberto Clemente (82,212 to 46,827), and he and the future Hall of Famer were the top finishers out-of-the-money for the rookie all-star team.13 King followed his rookie year with 15 homers in 118 games in 1956, batting .249. He battled a shoulder injury late in ’55 that flared up again in June 1956, but still led National League left fielders with nine assists in ’56.14

Frank Lane, the Cardinals general manager, wanted to get King back. He was sure King’s left-handed power stroke was well suited for the short right-field porch in the first Busch Stadium.15 With the Cubs in St. Louis the first week of the 1957 season, Lane and Cubs GM John Holland agreed on a trade of King to the Cardinals for outfielder Bobby Del Greco and pitcher Ed Mayer.16 But a month later, King surprisingly was optioned to Omaha. At a postseason luncheon, Lane, who had been fired during the season, said he and manager Fred Hutchinson had wanted to keep King and option young prospect Bobby Gene Smith, but had been overruled by club owner August Busch.17

In any case, King had a solid season playing for manager Johnny Keane at Omaha. He hit 20 home runs and was voted the team’s most popular player by the fans.18 The Cardinals were counting on King to strengthen the bench in 1958.19 As spring training wound down, however, St. Louis found itself short on catching depth, while the Giants were looking for a left-handed-hitting outfielder. On April 2 King was shipped to San Francisco for catcher Ray Katt.20

“I thought I’d get a better shot at playing with San Francisco,” King told Steve Bitker, author of The Original San Francisco Giants, published in 2001.21

Two weeks later, on April 15, 1958, King batted second for the Giants, ahead of Willie Mays, as two relocated teams from New York opened their seasons in San Francisco. With a strong wind blowing out to right field at Seals Stadium, Giants manager Bill Rigney replaced Hank Sauer, who had been scheduled to start in left, with King, who went 2-for-3 with two walks and a run batted in against Don Drysdale. But after that, his playing time was sporadic.22

On May 14, however, King ignited a furious ninth-inning Giants rally with a two-run pinch-hit double, the first of a record-tying three straight pinch hits in the inning that helped bring San Francisco back from an 11-1 deficit against the Pirates’ Vernon Law. When the dust had settled, Pittsburgh won, 11-10, as the Giants left the bases loaded.

For King, such highlights were few, so in mid-June, he was optioned to Phoenix. After 20 games there, he was transferred, along with pitchers Ernie Broglio and Ray Crone, to Toronto, which had no working agreement that season with a major-league club. The Giants got pitcher Don Johnson.23 This was more of a loan than a trade, as King and Broglio were recalled by the Giants in September.24 Although King played well defensively for the Maple Leafs, he was hampered by an injured wrist.25

With no major-league offers, King went to spring training in 1959 with Toronto, for whom he played all season.26 His wife and two young children lived in Toronto with him and enjoyed life there.27 The International League team still was not affiliated with a major-league club. The team had been purchased several years earlier by Jack Kent Cooke, later the owner of football’s Washington Redskins. Cooke was seeking a major-league franchise for Toronto, but after the ’59 season, he signed a working agreement with the Indians.28

After returning from a knee injury, King broke into the starting lineup with a hitting barrage that sparked the Maple Leafs to 22 wins in 31 games.29 At season’s end he was selected as the team’s player of the year.30 He was available in the major-league player draft on November 30, but no team selected him.31

King remained Toronto property for the 1960 season. Behind his solid hitting – 24 homers, 86 RBIs, .384 on-base percentage – and its stellar pitching, the team ran away with the International League title. Although he missed two weeks with the mumps, King was voted the league Most Valuable Player.32

Cooke let Cleveland acquire King and two Toronto pitchers for $15,000 each.33 Frank Lane, now the Indians GM, said he saw the purchase as the Tribe’s biggest offseason addition.34 Yet King was one of 15 Indians left unprotected when the American League expansion draft took place in December. The new Washington Senators took King along with 27 other players for $75,000 each, a tidy profit for the Indians for someone who had never played for Cleveland.35

Like many American professionals, King played winter ball. He was in Venezuela when he was selected in the expansion draft, on the Caracas roster for third straight season. He also had played briefly for San Juan in the Puerto Rican league in the winter of ’59. King’s widow and son both recall their father telling them about a day in January 1958 when the Caracas team was landing at the airport and armed troops were stationed along the runway. A coup led by officers who favored a return to democratic rule had just toppled the military government. The American players were rushed to their hotel and forced to remain there for the next week.36

King made the Washington team out of spring training, although he was slowed by a shoulder injury.37 He got a chance to play more frequently when Marty Keough lost his starting role in May.38 King’s first two home runs, on May 13 and 14, helped the Nats shut out Boston twice. Both homers cleared the 31-foot-high right-field wall in Griffith Stadium, long anathema to left-handed hitters. He finished the season hitting .270 with a .363 on-base percentage and a solid .811 OPS (on-base plus slugging percentage), thanks to 12 doubles, a triple, and 11 homers among his 71 hits in 306 plate appearances.

King’s performance was good enough that Senators general manager Ed Doherty rejected a trade in which the Twins would have sent the Nats outfielder Jim Lemon. The same trade was offered again in the spring 39and once more rejected. King was not untouchable: Doherty offered him to Cleveland – where Mel McGaha, King’s Toronto manager, was the field boss – for Vic Power. But the Indians did not bite.

The 1962 season began with King playing left field regularly against right-handers, but he got off to a slow start. By June he was playing mostly in right. He was the Nats’ only left-hand-hitting outfielder. Although his average fell to .243, he still had a respectable .353 OBP. He walked 55 times and fanned just 37 times all season. King usually made contact. This was one of three years in a row that he walked more than he struck out. For his career, he walked 363 times with 401 strikeouts in 3,338 plate appearances.

The 1963 season proved to be the low point for the expansion Senators. The team lost 106 games. Gil Hodges replaced Mickey Vernon as manager in May. George Selkirk had already replaced Ed Doherty as GM. But for King, ’63 turned out to be – by traditional measures, at least – his most productive season. He played more than he ever had before and reached career highs in home runs and RBIs. But his OBP dropped to .300. (By sabermetric measures, he did better in ’61 and would do better in ’64. His ’63 wins-above-replacement was just 0.8, but reached 2.0 in ’61 and 2.4 in ’64.)

Still, King’s homers and his powerful arm provided more than occasional thrills for diehard Senators fans. Perhaps the most memorable of his 12 outfield assists came on August 10, 1963, when his perfect throw from right field on a two-out, ninth-inning single nailed Luis Aparicio at the plate to preserve a 6-5 victory over the Orioles.40

As King approached 20 home runs, a brouhaha over team records erupted between the new Senators and the Twins, who had moved from Washington after the 1960 season. Vernon had set the Washington record for homers by a left-handed batter in 1954 with 20, playing his home games in cavernous Griffith Stadium. On August 15 King and the Twins’ Jimmie Hall each hit his 20th home run. Both teams claimed they had matched the record.41 The Sporting News on September 14 gave the publicity directors of both clubs space to state their cases about which team had the best claim.42 Today, most sources would attribute pre-1961 franchise records to the Twins, just as the expansion team’s records – if any – would be credited to the successor Texas Rangers. But none of that apparently was settled in 1963. In any case, Mike Epstein’s 30 homers in 1969 topped King’s Washington left-handed-batting mark.

King’s batting average suffered as he was pressed into regular service against left-handed pitchers. The Nats had little or no viable bench, so King kept playing through a 2-for-35 slump, and finished 1963 season at .231.43

A highlight, if it can be called that, of the dismal ’63 season was the battle between King and road roommate Don Lock for the team home-run lead. “We’ll be doin’ real good if both of us can beat Roger Maris’s record,” King joked. Lock’s 27 homers ended up beating out King’s 24.44 Among King’s personal highs in the ’63 season were his three homers in a doubleheader at Cleveland on June 14 and his two homers in a win over Boston at home on August 4.

Trade talk involving King abounded after the ’63 season. The Orioles, for instance, offered outfielder Jackie Brandt for him. Selkirk turned them down.45

The lowly Senators set a modest goal for the next season: “Off The Floor – In ’64” was the team’s slogan on the yearbook cover.46 Although the Nats again lost 100 games, they escaped the cellar. For King, a two-week stretch in 1964 included the best games of his career. On May 25 in Boston, he hit for the cycle, the only expansion Senator ever to do so. He tripled in his final at-bat. This was his lone triple of the season. (He was never fast.) His homer was a solo shot in the sixth. He had doubled home a run in the second. What made his cycle even more unusual was his single in the fourth. He was thrown out trying to stretch it into a double – an out that in retrospect he might be glad he made. Despite King’s heroics, the Red Sox won, 3-2.47

Two weeks later, at home on June 8, King belted three home runs against Kansas City. But all were with nobody on, and the Nats lost, 5-4.

“I hit all of them on high fastballs,” said King. “The only time they got me out, I was swinging at a curveball.”48 A tough man to fan, King for the most part tried to lay off breaking pitches, which likely accounts for his solid career walks-to-strikeouts ratio.49

By this time, his teammates had taken to calling him “Sky” King, a play not only on the old Saturday-morning TV series, but a playful dig at King’s dread of air travel. “I’d hug dad at the airport when he got back from the road,” and no matter the temperature “his shirt was always drenched with sweat,” his son David said.50 Jim King never got on another airplane after his major-league career ended, according to his wife, Rose. He turned down invitations to far-away old-timers games so he wouldn’t have to fly.51

Injuries and illness took their toll on King in 1964. Back trouble in late June kept him from swinging at full strength. His appendix began giving him trouble during a late-July series in New York, yet in pain, he delivered a two-run eighth-inning pinch single that beat the Yankees, 2-1.

“I had an attack” on June 22, King told author James Hartley in January 1997. “I played the next day. I couldn’t get around too good, but I pinch-hit with the bases loaded. … They threw it where I was swinging.”52

He was sent back to Washington for tests,53 but surgery was delayed until after the season, when he had his appendix removed. The recurring pain obviously wore on King. As the season ended he told Bob Addie of the Washington Post that he planned take a month off to go fishing, uncharacteristic for a man who worked a farm at home in Arkansas. “A man has to build up his energies after a tough season,” King told Addie – especially one facing surgery to have his appendix removed.

After the ’64 season, the Yankees renewed their interest in King, but no deal was worked out.54 Ralph Houk of the Yankees was especially persistent. “I’ve always liked that guy,” Houk said of King when the Nats finally traded him to Chicago in 1967. “With the left-handed power he’s got, he’d go big in Yankee Stadium.” Houk said he’d pitch around King “even when he was on the bench.”55

Houk’s Yankees were at it again in May 1965, offering infielder Phil Linz for King.56 As the 1966 season ended, New York was still seeking a trade for King.57 Yet King didn’t have extraordinary numbers against the Yankees, hitting near his career average against them with six homers over seven seasons.

Forced to rest over the winter after his appendix was removed, King was 15 pounds over his playing weight when he arrived in camp. This bothered him; he was always proud of being in shape. “They pay you to do your best, and I figure I owe them that,” he told Addie. As May began, he shook off the rust. On May 2 his pinch-hit RBIs won both games of a doubleheader.58 Despite not hitting his first homer until May 7, he proceeded to hit seven more in the next month – in a part-time role.

In June 1965, in a pregame promotion before a game in Los Angeles, King and Lock agreed to take part in a cow-milking contest as part of “dairy month” against Joe Adcock and Phil Roof of the California Angels. Presumably, King had milked cows before, although Black Angus beef cattle were the focus of his Arkansas farm. Lock was a Kansas farm boy. Despite their expertise, the pair lost to the Angels duo. It must have been home-field advantage.59

In 1966 King began bringing his young son to games at D.C. Stadium. Eight-year-old David would try to shag flies in the outfield during batting practice. “I used to take Dave with me into the clubhouse after games,” King said in 1976. “He generally raised a lot of hell with my teammates” – except one: Dad said his boy was intimidated by the size of the Nats’ massive slugger Frank Howard. During his years in Washington, King’s wife and his two children lived with him in the D.C. suburbs during the season, until school resumed in Arkansas.60

Making himself useful, King caught two innings for the Nats in the second game of a June 1967 doubleheader after the starting catcher left for a pinch-hitter and the backup got ejected.61 King had caught previously during a game with Toronto and one game with the Senators in 1961.

King’s pinch-hitting opportunities increased during his last four seasons in Washington, with at least 40 appearances a year in that role. Over his career, he made 332 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter and compiled a .337 on-base percentage. “Naturally, a fellow likes to be in the lineup every day, but when you deliver as a pinch-hitter, you get a big thrill,” King said in 1965.62

At age 34, King’s years with the Senators abruptly ended on June 15, 1967, when he was traded to the White Sox for speedy outfielder Ed Stroud. King took it hard. “I don’t want to leave Washington,” a tearful King told Hodges when informed of the trade.63 “We loved Washington – the people, the park, guys on the club,” King told Hartley in 1997. “I always enjoyed playing in Washington.” He also loved playing for his manager: “I thought the world of Gil Hodges.”64

King had little success after he left the Senators. A month after his trade to Chicago, he was sent to the Indians in a deal that brought Rocky Colavito to the White Sox. When the Indians released King at end of the ’67 season, he decided to call it quits, disappointed at how it ended.

“That last year was just miserable for me,” King said in a 1976 interview. “I broke my right hand. I didn’t get to play enough. Things just started going bad. … It was time to get out.” Still, he said he missed “everything” about his time in the majors – with the exception of the air travel. “I never once relaxed on a plane,” he recalled.”65

Back in Elkins, King was asked to play for an insurance company-sponsored team that also featured longtime University of Arkansas baseball coach Norm DeBriyn.66 The team won the state championship and was ranked in the top 10 nationally among National Baseball Congress teams one year. By then in his late 30s, King played mostly against younger pitchers, many of whom would try to blow a fastball by a bald guy who looked old enough to be their father. To their amazement, those fastballs often ended up over the outfield fences. King also coached son David, who became a successful high-school football coach, in Little League, Pony League, and Babe Ruth Baseball.67

In the 1976 interview, King said he was happy to be home in Elkins and had no desire to coach in the majors. “I’ve never seen a big-league game in person since I left,” he said.68 Surrounded by family and beloved by his grandchildren, who called him “KK,” King was content to live out his years in his hometown.69

He took a job with the local telephone company, where he remained for 24 years until he retired, while working his farm, where he raised cattle, hogs and chicken. He worked first as a lineman for the phone company and later as a foreman of a crew laying underground wires. All of which kept King very busy, until he was slowed by a hip replacement and knee problems in the years before his death.70 King is buried in Mt. Olive Cemetery in Elkins.

“There was not a lazy bone in his body,” his son David recalled.71

Sources

The primary sources for this biographer:

Hartley, James R. Washington’s Expansion Senators (1961-1971) (Germantown, Maryland: Corduroy Press, 1997-98).

Northwest Arkansas Times, 1976.

The Sporting News, 1954-1967.

Baseball-reference.com.

Telephone conversation between the author and David L. King, February 1, 2017.

Telephone conversation between the author and Rose King, February 2, 2017.

Notes

1 Obituary, Arkansas Online, m.arkansasonline.com/obituaries/2015/feb/25/james-king-2015-02-25/.

2 Telephone conversation with Rose King, Jim King’s widow, February 2, 2017.

3 Obituary, Arkansas Online.

4 Telephone conversation with David L. King, Jim’s son, February 1, 2017.

5 “Cardinals Prepared Jim King for Big League career,” retrosimba.com/2015/03/01/cardinals-prepared-jim-king-for-big-league-career/, March 1, 2015.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Robert Phipps, “DiMag, Dean Help Fill Park for TV Party,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1954: 41.

9 “Outfielder Hurls No-Hitter – Loses, 1-0, on Errors,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1954: 32.

10 Telephone conversation with David L. King.

11 “Cardinals Prepared King.”

12 John C. Hoffman, “Hack Counts His Blessings – and Then Pencils a Want List,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1955: 11; Hoffman, “Cubs Finding Their Worries Are Mostly of Garden Variety,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1955: 21; Hoffman, “Hack Yearns for His Departing Daisies as He Cuts Cubs to Size,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1955: 9.

13 Bob Broeg, “Fans Name Only Five Repeaters in Balloting for Starting Lineup,” The Sporting News, July 13,1955: 9;

Broeg, “A.L. Places 8 of 11 on All-Rookie Team,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1955: 5.

14 National League brief, The Sporting News, June 20, 1956: 20.

15 Broeg, “Anyone to Deal? Cards Rich at Shortstop and First Base,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1957: 16.

16 “Cardinals Prepared King.”

17 Broeg, “Cards Front Office Blocked Bobby Gene Optioning – Lane,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1957: 6.

18 American Association brief, The Sporting News, September 18, 1957: 42.

19 Broeg, “Cards Want Outfield Help,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1957: 4.

20 Broeg, “Jim King Shipped to Giants, Katt Back With Cardinals,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1958: 28.

21 Steve Bitker, The Original San Francisco Giants, (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 2001), 232.

22 Ibid.

23 Cy Kritzer, “Loop’s Gate Mark Nearing 1,200,000,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1958: 29.

24 Bob Stevens, “Giants Bring Up Rodgers and Zanni, But Pass Up Recall Option on Rhodes,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1958: 9.

25 Neil MacCarl, “Ernie Broglio, Leaf Work Horse, Best With Only Two Days of Rest,” The Sporting News, September 24, 1958: 39.

26 Telephone conversation with Rose King.

27 Ibid.

28 MacCarl, “Peddling by Cooke Can Turn Ink Black,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1960: 31.

29 International League brief, The Sporting News, July 8, 1959: 40.

30 International League brief, The Sporting News, September 16, 1959: 34.

31 Edward Prell, “What’s This? Washington’s First!” The Sporting News, November 18, 1959: 13 (16).

32 MacCarl, “King, Cicotte Cop Awards for Int Stars,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1960: 60.

33 “Peddling by Cooke.”

34 Hal Lebovitz, “Lane Takes Bucs Cue, Eyes a ‘Face’ to Aid Tribe,’ The Sporting News, October 26, 1960: 27.

35 Hy Hurwitz, “New Clubs Pleased With $4 Million Picks,” The Sporting News, December 21, 1960: 3 (4).

36 Telephone conversations with David L. King and Rose King, February 1 and 2, 2017.

37 Shirley Povich, “Gardeners Hinton, King Reap Harvest of Bingles for Nats,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1961: 4.

38 Povich, “Nats Popping Buttons Over Hill Dazzlers,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1961: 15.

39 Bob Dolgan, “Pilot McGaha Tosses Tantrum Over Tribe Shoddy Showing,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1962: 32.

40 James R. Hartley, Washington’s Expansion Senators (1961 -1971) (Germantown, Maryland: Corduroy Press, 1997, 1998), 33.

41 Bob Addie, “Confusion Over Washington Club Records,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963: 14.

42 Herb Heft and Burton Hawkins, “Records, Records, Who’s Got Washington Records?” The Sporting News, September 14, 1963: 13.

43 Povich, “Nats Owners Swim in Sea of Red Ink – Back Building Plan,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1963: 8.

44 Addie, “Roebuck, Burnside Rush to Aid of Injury-Riddled Nat Hill Staff,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1963: 16.

45 Povich, “Senators to Use Bridges as Link to Land of Plenty,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1963: 24.

46 Hartley, 36.

47 Ibid.

48 United Press International, “Three Homers ‘Luck.’”June 9, 1964, clip from unidentified newspaper in King’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Giamatti Research Center, Cooperstown, New York.

49 Telephone conversation with David King.

50 Ibid.

51 Telephone conversation with Rose King.

52 Hartley, 41.

53 Addie, “Limping Senators Resemble Cast for TV Hospital Drama,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1964: 18.

54 Addie, “Gil Dreads Thought But He May Give Up, Put Hinton on Block,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1964: 17.

55 Major Flashes/American League brief, The Sporting News, July 8, 1967: 27.

56 Addie, “Nats May Get Phil Linz in Deal for King,” Washington Post, May 9, 1965: C3.

57 Addie, “When Nats Hit Road, Even AAA Unable to Help,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1966: 17.

58 Addie, “King New Monarch of Senators Bench With Clutch Clouts,” The Sporting News, May 22, 1965: 19.

59 Ross Newhan, “Angels Land Right Side Up by Making Lefthand Turn,” The Sporting News, June 19, 1965: 20.

60 Telephone conversation with David King; Dennis Jackson, “Jim King Regales Listeners With Stories About the ‘Bigs,’ ” Northwest Arkansas Times, July 30, 1976: 11; Telephone conversation with Rose King.

61 Addie, “Epstein Addition to Nat Lineup Takes Hitting Heat Off Howard,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1967: 16.

62 Addie, “King New Monarch.”

63 Major Flashes/American League brief, The Sporting News, July 1, 1967: 22.

64 Hartley, 69.

65 Jackson, “Jim King Regales Listeners.”

66 Telephone conversation with Rose King.

67 Telephone conversation with David King.

68 Jackson, “Jim King Regales.”

69 Telephone conversation with Dr. Ashley King-Tinsley, King’s granddaughter, January 31, 2017.

70 Telephone conversation with David King.

71 Ibid.

Full Name

James Hubert King

Born

August 27, 1932 at Elkins, AR (USA)

Died

February 23, 2015 at Fayetteville, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.