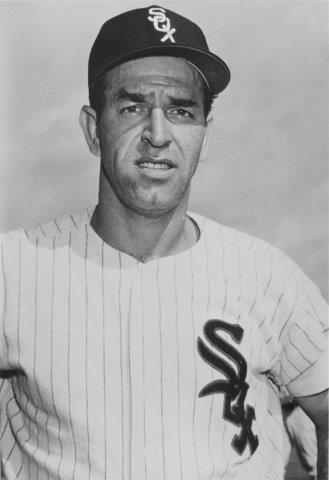

Jim Rivera

Speedy outfielder Jim Rivera was one of the great characters of 1950s baseball. As Chicago White Sox general manager Ed Short put it, “Jungle Jim may not have the fattest average in baseball, but he gives the fans a show with his daredevil running and sliding, his terrific fielding, and clutch hitting.”1 His all-out style made him one of the most popular White Sox, despite his troubled — and sometimes troubling — history.

Manuel Joseph Rivera was born in New York City on July 22, 1921 to a family of six brothers and five sisters.2 Of Puerto Rican heritage, he was raised near 112th and Madison in the impoverished section of Manhattan known as Spanish Harlem.3 He lived there until his mother died when he was 6 years old.4 With his father unable to care for everyone in the family, he was sent to an orphanage in Blauvelt, New York, about 15 miles up the Hudson from the city, run by a congregation of Dominican sisters. He lived at Saint Dominic’s for the next 10 years while he received formal education and learned to play various sports, including baseball.5

After he turned 16, Rivera returned home to live with his remarried father. With the family on relief, Rivera took various jobs to support them. Construction work helped build his strength, and he joined other friends from the neighborhood in learning how to box.6 By the time he was 17, he started fighting amateur bouts around New York City along with St. Dominic’s classmate Jim Dorso. Since he was constantly hanging around with Dorso, others began calling Rivera “Jim,” a name that would stay with him for the rest of his life.7 During this time he was still playing baseball. He became good enough to join a semipro team representing the Valencia Bakery, and left the world of amateur boxing.8

Rivera resumed boxing after joining the Army Air Corps in August 1942, and captured the light-heavyweight title of his outfit in the Third Air Force at Camp Barkley, Texas.9 He played baseball on the camp team. In the spring of 1944, his life was thrown into turmoil. He was charged with raping and assaulting the daughter of an Army officer after a dance at Barksdale Field, Louisiana. After a medical examination of the accuser, the charge was reduced to attempted rape. Rivera was found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment. After serving five years in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, he was paroled in 1949.10

Rivera played baseball on the prison team. His success in games against local teams outside the prison caught the attention of Atlanta Crackers owner Earl Mann. Mann worked with authorities to secure a parole for Rivera. When he was released in March 1949, a contract with the Crackers was waiting for him.11 Atlanta farmed Rivera out to Class-D Gainesville, where the 27-year-old, 6-foot, 198-pound left-handed outfielder hit .335, stole 55 bases, and scored 142 runs, leading the G-Men to the Florida State League pennant.12 Promoted to Class-B Pensacola the next year, he hit .338, scored 139 runs, and drove in 135 to spark the Fliers to the Southeastern League pennant.13

In the 1950 offseason, Rivera played for the Caguas team in the Puerto Rican winter league. He began to slide head-first into bases, a style that became a trademark during his major-league career. Rogers Hornsby, who was managing an opposing team in the league, took an immediate liking to him and provided the player with advice and coaching. Hornsby would soon refer to Rivera as “the only man I would pay admission to see.”14

When Hornsby was named manager of the Seattle club in the Pacific Coast League for 1951, he approached Rivera about joining him. Seattle bought him from Pensacola for $2,500.15 Rivera enjoyed his finest professional season in Seattle, collecting 231 hits, scoring 135 runs, hitting a league-leading .352, and leading the Rainiers to the pennant — his third in three professional seasons. His speed and dazzling play garnered him the league’s MVP award.16 One reporter said, “He runs in the outfield like a deer, on the bases like an express train, and he throws like a rifle.”17 His exceptional play caught the attention of major-league clubs. In July the White Sox exercised their option to purchase his contract for $65,000, instructing him to report at the end of the PCL season.18

In the fall of 1951, Hornsby was named manager of Bill Veeck’s St. Louis Browns. Hornsby urged Veeck to acquire Rivera.19 Veeck sent catcher Sherman Lollar to Chicago in a three-team, eight-player deal that brought Rivera to the Browns.20 But the deal caused a stir in St. Louis. Local civic and religious groups began a campaign to have Rivera dismissed from the Browns roster and banned from baseball. In response to the pressure, Commissioner Ford Frick stated, “If the purpose is punishment, then he has already been punished. If the purpose is cure or improvement, then this man has a greater chance to make good being allowed to live as others live. Since Rivera came into baseball his conduct has been beyond question. If in the future he shows that he has not profited by his experience, this office will take action.”21

Although there were high hopes for Rivera and the rookie-laden Browns in 1952, neither started the season well. Rivera did collect a hit in his major-league debut on Opening Day in Detroit, but he fell into a slump. By the start of May he was on the bench. On May 8 he came into a game in Philadelphia as a defensive substitute, made a sensational catch and hit a ninth-inning home run to win the game for the Browns.22 That put him back in the lineup, although the team’s fortunes did not improve. Hornsby, under constant criticism for continuing to play the slumping rookies, was fired in mid-June.23 Rivera soon followed him, traded back to the White Sox at the end of July.24

Rivera’s White Sox debut on July 29, 1952, was a memorable one. In front of a crowd of nearly 39,000, he started in center field and picked up hits in his first two at-bats, helping the Sox build a 7-0 lead over the New York Yankees. The Yankees came back to win that game on Mickey Mantle’s ninth-inning grand slam. Rivera homered the next day to lead the White Sox to a win over the Bronx Bombers.25 Soon his speed on the bases and acrobatic catches made him a fan favorite. Big Jim, as he liked to be called, finished the year with a .253 average, but the 13 stolen bases he collected in two months with the White Sox showed signs of promise.

On the last day of the season, Rivera was arrested in the White Sox clubhouse on charges that he had raped the wife of a soldier.26 He contended that the relationship was consensual, and took a lie detector test. After he passed, a Chicago grand jury declined to indict him.27 Commissioner Frick placed him on “indefinite probation.” Frick put full responsibility for Rivera’s future behavior on the White Sox, and prohibited the team from trading or selling him for a year.28 This generated more controversy in the press from those who opposed and those who supported his right to play.

Rivera responded by enjoying his finest years in the majors.29 In 1953 he played center field in almost every game and reached double figures in doubles, triples, and home runs. His 16 triples led the American League while his 22 stolen bases trailed only his outfield teammate Minnie Minoso. His efforts helped the White Sox win 89 games, their best record in more than 30 years. Both the White Sox and Rivera did even better in 1954, as the team won 94 games and Rivera hit a career-high .286. He continued to dazzle in the field and on the bases, but was now patrolling right field with Johnny Groth in center. During this year Rivera’s habit of flapping his arms to wave his fellow fielders off fly balls led Chicago Sun-Times sportswriter John Hoffman to call him Jungle Jim.30 The nickname quickly became popular and has stayed with him.

In 1955, Rivera led the American League with 25 stolen bases, but his average dropped to .264 as a pronounced hitch in his swing took its toll.31 The White Sox participated in their first real pennant race in 35 years and were not eliminated until late September. In an effort to become more competitive in 1956, the team swung an offseason deal for slugging outfielder Larry Doby.32 Deals in May brought veteran outfielders Jim Delsing and Dave Philley.33 Rivera’s playing time was reduced as his average fell to .255.

After the season ended, Rivera married his second wife, Phyllis Crain of Angola, Indiana.34 This time was the peak of his popularity in Chicago. Sportswriters could always count on him for a good quote or funny story, and he was in constant demand for personal appearances.35 An avid filmgoer, Rivera would sometimes take in two movies in a day before a night game and developed the reputation as the team’s “film critic.”36 Rumors of potential trades never came true, as he was deemed too popular to move.

When the White Sox acquired even more outfielders, Jungle Jim opened the 1957 season at first base, but was shifted back to right field in June after the Sox acquired veteran first baseman Earl Torgeson.37 Rivera shared the outfield job with rookie Jim Landis, and his 14 home runs tied for the team lead with Larry Doby. In 1958 Rivera competed for playing time with Don Mueller, Tito Francona, and Bubba Phillips as his average plummeted to .225. His days as a regular had ended, and he began the transformation into a solid bench player.38

Rivera contributed on the field to the 1959 White Sox pennant-winning team as a late-inning outfielder, pinch-runner, platoon starter, and pinch-hitter. He contributed off the field with his great enthusiasm for the game and energy. He was praised for staying in excellent shape despite being used sparingly, and for being “the first man in uniform before every game.”39

Rivera’s second at-bat of the season, on April 17, produced a victory over the Detroit Tigers as his two-run double in the eighth inning broke a 4-4 tie.40 Later in the month, he was inserted into the starting lineup for a few games to spell the slumping Johnny Callison.41 He suffered a broken rib making a tumbling catch in a game against the Yankees and went on the disabled list.42

When he came back toward the end of May, Rivera returned to the bench.43 He made the most of a spot start in a June 7 doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox, contributing a pair of hits in each game.44 He started in right field for the rest of the month, but a batting slump reduced him to a platoon role.45 He pulled a muscle on July 5, and went back to the bench when he recovered.46 Rivera replaced the injured Jim McAnany on August 21, and his leaping catch against the right-field wall preserved a close victory over Washington.47 He platooned with McAnany for the rest of the season.

On the evening of September 22, the White Sox took on the Cleveland Indians in Cleveland with the opportunity to clinch the pennant. Since right-hander Jim Perry was starting for the Tribe, Rivera was in the lineup. The Sox took an early 2-0 lead, but the Indians battled back for a run in the bottom of the fifth. Mudcat Grant relieved Perry in the top of the sixth and surrendered a one-out home run to Al Smith. Rivera followed with a home run to right-center. The lead held up as the White Sox earned their first title in 40 years.48 Rivera called the homer in the pennant-clinching game his best moment in baseball.49

Rivera continued platooning with McAnany in the World Series, starting games One, Three, and Four while going 0-for-11 at the plate. He made his most memorable impact in a game he did not start. After the Los Angeles Dodgers had gained a three-games-to-one Series lead, left-hander Sandy Koufax pitched Game Five in front of a record crowd in the Los Angeles Coliseum. The White Sox squeaked out a run in the top of the fourth inning on a double play, but the Dodgers constantly threatened to come back against Chicago’s Bob Shaw. After two runners reached base in the bottom of the seventh with two outs and the hot-hitting Charlie Neal coming up, White Sox manager Al Lopez inserted Rivera in right field. The move proved prescient as Neal laced a drive toward right-center that looked certain to clear the bases. Rivera raced back and made an over-the-shoulder catch at the fence to preserve the 1-0 lead and the game.50

In 1960 Minnie Minoso returned to the White Sox and Rivera’s role was reduced to that of a late-inning defensive replacement and pinch-runner.51 Although he appeared in 48 games, he started only once and collected a mere 17 at-bats. The following year Rivera again made the White Sox as a reserve, but he fractured his thumb in his first pinch-running assignment while sliding head-first into third.52 That slide proved to be Rivera’s last play with the Sox; upon his return from the disabled list in June he was released.53 He was picked up by the Kansas City Athletics, who expressed plans to use him as a “general all-around utility man.”54 He actually ended up back in a platoon role, playing mostly right field and finishing 1961 with a .241 batting average. When the Athletics released him at the end of the year his major-league career was over.55

After the season, Rivera managed in the Puerto Rican League and signed with the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association to be a player-coach.56 His stint with the Indians did not last long. By July he was back with Seattle in the Pacific Coast League.57 He stayed with the Rainiers through June 1963, when he was given his unconditional release. At the time he was batting .259 with two homers.58 It was the end of his professional baseball career in the US, but he still wasn’t done; signing with the Mexico City Tigres of the Mexican League, he finished the 1963 season south of the border and then played in 87 games for the Mexican League Jalisco Charros in 1964 before finally retiring for good.

Residing in his wife’s hometown of Angola, Indiana, Rivera bought a restaurant on Crooked Lake known as the Captain’s Cabin.59 There he reigned as proprietor for over 20 years, regaling customers with stories of days past until he retired to Port Charlotte, Florida, in 1990.60 He remained loyal to the White Sox, and could always be counted on to make appearances in old timers’ games and social events.61 When Bill Veeck announced plans to have his team wear short pants during the 1976 season, Jungle Jim was there to model them.62 When the White Sox brought out members of the 1959 World Series team before Game One of the 2005 World Series, Jungle Jim was on the field.63 He died at age 96 in Fort Wayne, Indiana, on November 13, 2017.64

An updated version of this biography is included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It first appeared in “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda.

Notes

1 David Eskenazi, “Wayback Machine: Rajah, Rivera, ’51 Rainiers,” SportsPressNW.com, March 27, 2012.

2 There has been some confusion about Jim Rivera’s year of birth. The date of birth appearing in many 1950’s articles, baseball cards, and press releases — July 22, 1923 — does not match the date of birth Rivera told to friends and personally gave on questionnaires returned to the White Sox — July 22, 1921. Turkin & Thompson’s 1963 version of the Encyclopedia of Baseball and subsequent versions of that book show the date as July 22, 1922. The current standard references (such as Baseball-reference.com) give the date as July 22, 1921 and that is what is used here. David Condon made sport of the two-year discrepancy in his Chicago Tribune “In the Wake of the News” column printed on June 13, 1963.

3 Milton Gross, “The Jim Rivera Story,” Sport, June 1952: 17.

4 Bob Vanderberg, Sox, from Lane and Fain to Zisk and Fisk (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 1982), 156.

5 Gross, 74.

6 Gross, 74.

7 Warren Brown, “Jim Rivera Talking …,” Sport, October 1955: 21.

8 Brown, 34.

9 Gross, 74.

10 Gross, 74-75.

11 Gross, 75.

12 Joe Halberstein, “Jim Rivera recalls G-Men playing days in ’49,” Gainesville Daily Sun, August 11, 1957;

13 Vanderberg, 158.

14 Harry Grayson, “Sport City,” Portsmouth Herald, August 30, 1955.

15 Eskenazi.

16 Steve Krevisky presentation at SABR 36 in Seattle, Washington, 2006: “Jungle Jim Leads the Way! The Saga of the 1951 PCL Champs, The Seattle Rainiers;” Perpetual Motion Pictures video: The Seattle Rainiers, 2006.

17 Eskenazi.

18 Vanderberg, 158.

19 Vanderberg, 158.

20 Irving Vaughan, “Sox Get Lollar, Widmar, and Dente,” Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1951: C1-C2.

21 Eskenazi.

22 “Rivera Stars as Browns Top Athletics, 9-8,” Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1952: C3.

23 “Hornsby Fired; Marion Manages Browns,” Chicago Tribune, June 11, 1952: B1, B3.

24 Irving Vaughan, “White Sox Get Rivera — Again,” July 29, 1952: B1.

25 Vanderberg, page 159.

26 “Arrest Jim Rivera, Sox Center Fielder, on Rape Complaint,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1952: 6; “White Sox’s Rivera Charged with Rape of Soldier’s Wife,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1952: 5.

27 “Jury Refuses to Indict Rivera on Rape Charge,” Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1952: 4; Vanderberg, 159.

28 “Sox’s Rivera Draws Indefinite Probation,” Chicago Tribune, November 13, 1952: d1.

29 Edward Prell, “That amazing Sox Outfield!” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1955: k27.

30 Brown, 21.

31 Vanderberg, 160.

32 Edward Prell, “Sox Trade Carrasquel, Busby for Doby,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1955: C1, C4.

33 “Trade Winds Blow,” Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1956: C1, C3; Edward Prell, “Sox Trade Kell, 3 Others for 2 Orioles,” Chicago Tribune, May 22, 1956: C1, 2.

34 “Sox’s Rivera Takes Indiana Girl as Bride,” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 1956: B3.

35 Brown, 87.

36 Brown, 85-86.

37 “White Sox Get Torgeson for Philley, Cash,” Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1957: C2.

38 Edward Prell, “White Sox Figures Prove Left Is Right—Sometimes,” Chicago Tribune, November 20, 1957: C2; Edward Prell, “White Sox Train New Guns on Yank Dynasty,” Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1958: b2.

39 Richard Dozer, “Sox Opener in Boston Called Off by Rain,” Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1959: A4.

40 Richard Dozer, “Cubs Win, 9 TO 4; Sox Beat Tigers, 6 TO 5,” Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1959: E1, 2.

41 “Jim Rivera to Move Into Sox Lineup,” Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1959: A7.

42 “Batting Drill Pitch Puts Mantle Out,” Chicago Tribune, May 1, 1959: E6; “Sox Get Ennis from Reds for Rudolph,” Chicago Tribune, May 2, 1959: A2.

43 Richard Dozer, “Sox Win, 2-1; Cards Beat Cubs in 14th, 3-1,” Chicago Tribune, May 23, 1959: A1, 2; Baseball-reference.com.

44 Richard Dozer, “Beat Boston, 9-4 in 1st; Drop 2d, 4-2,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1959: C1, C4.

45 http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.fcgi?id=riverji01&t=b&year=1959

46 Richard Dozer, “Nellie, Luis Click Again; Smith, too!” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1959: C1, C5.

47 Edward Prell, “White Sox Win Again by One Run, 5-4!” Chicago Tribune, August 22, 1959: 1-2; Vanderberg, 160-161.

48 Edward Prell, “White Sox Win Pennant!” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1959: 1-2; Vanderberg, 161.

49 Joe Goddard, “What’s Up with Jim Rivera,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 18, 2002: 98.

50 Edward Prell, “Sox Win; Final at Home,” Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1959: 1-2; “Alston Lauds Lopez for Rivera Switch,” Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1959: E13; Vanderberg, 161.

51 Edward Prell, “Sox Acquire Minoso Again; Cubs Get Frank Thomas,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1959: E1; Edward Prell, “Sox Chorus: ‘I’m Growing Old’,” Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1960: C1, 2.

52 “Jim Rivera Is Placed on Disabled List,” Chicago Tribune, April 24, 1961: C4.

53 “Sox Release Rivera with ‘Reluctance’,” Chicago Tribune, June 7, 1961: C1; David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1961: C1.

54 “Rivera Flies to New York, Signs with A’s,” Chicago Tribune, June 10, 1961: C2.

55 Vanderberg, 161.

56 “Joe Horlen, Sox Hurler, OK’s Terms,” Chicago Tribune, January 16, 1962: C3; “Jim Rivera Indianapolis Player-Coach,” Chicago Tribune, February 20, 1962: B3.

57 “Jim Rivera Returns to Coast League,” Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1962: C5.

58 “Seattle Club Gives Release to Jim Rivera,” Chicago Tribune, June 12, 1963: E3.

59 Robert Goldsborough, “Whatever happened?” Chicago Tribune, July 16, 1967: E2; Vanderberg, 154.

60 Joe Goddard, “What’s Up with Jim Rivera,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 18, 2002: 98.

61 Richard Dozer, “John Pitches 5-0 Shutout; Horlen Triumphs, 4-1,” Chicago Tribune, August 1, 1966: C1, C4; David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 1969: C1; “’Old’ Cubs, Sox Meet Today,” Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1971: B2.

62 Bob Verdi, “Will sexy garb fit Sox knee-ds?” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1976: E3; Chicago Tribune, David Condon, “Opinions flow from all sides on Sox outfits,” Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1976: E3.

63 Melissa Isaacson, “Aparicio, teammates usher in the Series,” Chicago Tribune, October 23, 2005: 17. An update in 2017: After the World Series Rivera continued to show up for White Sox events. He came to SoxFest in 2009 where the author had the opportunity to briefly meet him and later that year participated in festivities surrounding the 50th Anniversary celebration of the White Sox 1959 AL Championship. According to David Hughes (a friend of Jim), he has lived in Fort Wayne, Indiana for the past 20 years while still spending winters in Port Charlotte.

64 ‘Jungle Jim’ Rivera, who played for ‘Go-Go’ White Sox, dies at age 96, http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/21415158/jungle-jim-rivera-former-chicago-white-sox-outfielder-dies-96; accessed January 21, 2018.

Full Name

Manuel Joseph Rivera

Born

July 22, 1921 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

November 13, 2017 at Fort Wayne, IN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.