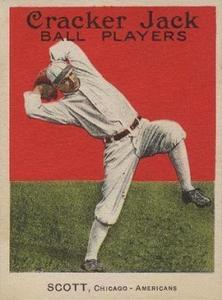

Jim Scott

The Chicago White Sox won its only two championships of the 20th century in 1906 and 1917. In between those two glorious seasons, the team fell back to the middle of the pack in the American League, but were always competitive, due in large part to the unheralded and hard luck hurling of a burly right handed pitcher from Wyoming, Jim “Death Valley” Scott. Although more often than not ending up on the wrong end of the score, Scott spent 25 years working in major and minor league baseball as a pitcher and umpire, and remains as one of the leading pitchers in franchise history.

The Chicago White Sox won its only two championships of the 20th century in 1906 and 1917. In between those two glorious seasons, the team fell back to the middle of the pack in the American League, but were always competitive, due in large part to the unheralded and hard luck hurling of a burly right handed pitcher from Wyoming, Jim “Death Valley” Scott. Although more often than not ending up on the wrong end of the score, Scott spent 25 years working in major and minor league baseball as a pitcher and umpire, and remains as one of the leading pitchers in franchise history.

Jim Scott was born in Deadwood, South Dakota on April 23, 1888. His father worked for the Federal Weather Bureau in the region and moved his family twice by the time young Jim was five years old, finally settling in Lander, Wyoming. Jim attended public schools in Lander, and by his own account, had his education and future all planned out. After finishing school in Lander, Scott was set to enroll at Wesleyan University in Nebraska and become a physician. However, baseball intervened and Scott would never finish his schooling.

Scott had played part time at third base for a local team coached by Bill McMahon, a former professional player. At one such game in 1907 against an army team, Scott was asked to take the pitching mound after the team’s starter had been knocked out. In his own words, Scott knew nothing about pitching but to “fire the ball over and pitch a curve when I felt like it”. However, the beginner was good enough to shut down the team the rest of the way, earning the attention of J.P. Cantillon, a local railroad official whose brother Joe Cantillon managed a team in Des Moines in the Iowa State League.

Cantillon convinced his brother to give Scott a tryout, and gave him a ticket to Des Moines. The young pitcher left school and reported to the team in Iowa, showing up dressed in overalls and tennis shoes. Decidedly unimpressed, Cantillon let Scott hang around for a couple of weeks before sending him packing. Undaunted, Scott traveled sixty miles to Oskaloosa, where he talked his way on to the local ball club. As fate would have it, his first start was a shutout win against Des Moines. Cantillon then attempted to talk Scott back on his team by claiming he was still under contract. Jim ignored him, and would later take special pleasure in beating Cantillon’s teams when the latter managed the Washington Senators.

Next stop for Scott was the Western Association, where he won 30 games for Wichita and set a league record with sixteen strikeouts in a game. Scott was able to dominate opposing batters by a combination of a hard curveball and tricky spitball. His exploits caught the eye of several big league scouts, and became property of the Chicago White Sox who bought his contract for $2,000 for the 1909 season.

Scott rolled into Chicago with high expectations and a brand new nickname: “Death Valley” Scott. The moniker was earned in part due to confusion on Scott’s place of birth, and part due to association with an infamous Western prospector and con man also named Death Valley Scott who arrived in Chicago on the same train as the pitcher. His debut on April 25 was certainly an auspicious one. Pitching in what Chicago Tribune reporter Ring Lardner described as “arctic weather” Scott dazzled the capacity crowd by shutting out the St. Louis Browns 1-0, striking out 6 and getting his first major league hit as well. This started him on the way to a fine rookie season, winning 12 games and posting a 2.30 ERA in 250 innings. Lardner later made Scott a peripheral character in his dead ball classic, You Know Me Al.

The White Sox struggled in 1910, falling to sixth place largely due to an offensive attack that ranked near the bottom of every league category. Scott’s 8-18 record reflected the lack of support, as he posted a 2.43 ERA. Despite the losing record, Scott’s pitching drew the respect of opponents and the media. He mixed in a screwball and spitball with his harder pitches, and used what was called a “clockspring” delivery to further confuse opposing hitters. He possessed a excellent pickoff move, and also frequently worked in relief between starts, leading the team that season with 18 relief appearances. In 1911, the team improved to fourth place, and Scott posted a 14-11 record, one of only two winning seasons in his career. Chicago newspaper accounts of games frequently bemoaned the hard luck losses of Death Valley Scott–although one reporter gave him the Biblical monikers of “Intrepid Nimrod” or “Wyoming Nimrod”. In the off season, Jim returned to Lander as a hero, and enjoyed his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and motorcycle riding.

The 1912 season was a lost one for Scott. He started well, pitching an entire 15 inning scoreless tie against Washington on April 20. The extended outing developed into a case of rheumatism that limited the pitcher to six games that season. In 1913, he recovered to become the staff ace and record a remarkable season. Scott started 38 games, completing 27, and relieved in 10 others to throw a total of 312 innings. He also achieved a rare feat of winning and losing 20 games in the same season. His 1.91 ERA still makes him the only pitcher in major league history to lose 20 games with an ERA less than 2.00. After the season, he joined teammate and close friend Buck Weaver and other big league stars on a goodwill tour to Asia, Australia, and Europe.

The highlight of Scott’s 1914 season came on May 14, in an outing that would (albeit temporarily) put him in the record books. Scott faced the Washington in Griffith Stadium that afternoon, matched up against second year pitcher Doc Ayers. Giving the performance of a lifetime, Scott held Washington hitless for nine innings, walking 2 batters in the 8th and overcoming two errors by Lena Blackburne. However, Ayers was equally as tough, and despite having several runners reach third, the White Sox were unable to score either. The game went into extra innings, and Chicago failed again after getting two runners on base in the top half of the tenth. In the bottom of the inning, Scott’s luck ran out. Future Black Sox Chick Gandil led off the inning with a clean single to center. Howie Shanks followed with another base hit to right field that took a bad hop past outfielder Ray Demmit to score the winning run. The hard luck loser would be credited with a no-hitter for over 75 years until the criterion for an “official” no hitter was changed. After the season, Scott joined Weaver on tour again–this time as part of a vaudeville routine with Weaver’s wife and sisters in law. The act’s best result was a romance that blossomed between Scott and co-performer Hattie Cook, whom he married in 1917.

Scott’s luck, as well as the White Sox, improved in 1915. Under new manager Pants Rowland, the big right hander had the best season of his career. Supported by an improved offensive attack (the Sox scored 230 more runs than the previous season) Scott won 24 games with a 2.04 ERA and tied Walter Johnson for the league lead in shutouts with 7. He continued to help the team by relieving between starts, finishing second in the league in appearances with 48, and was in the top five in the American League in seven different pitching categories. Although Scott struggled with a 7-14 record in 1916 (though with a still creditable 2.73 ERA) the team improved to second place and seemed poised from greatness in 1917.

The White Sox did go on to win their second (and so far last) World Series championship in 1917. Unfortunately for Scott, he was not around to be part of it. His 1917 season did have one highlight when he stopped Ty Cobb‘s 35-game hitting streak, and his 1.87 ERA was the best of his career. However, events outside the diamond led to the end of his major-league career. The patriotic Scott was one of the first major league players to enlist after the U.S. declared war on Germany, leaving the team in the late summer to report to training in San Francisco. Although he had only two winning seasons in his career, his 2.32 ERA ranks as the twelfth lowest of all time.

Scott received training as a supply depot officer but did not make it overseas before the war ended. He then went to work in a foundry in Beloit, Wisconsin, where he also pitched for a company team. Offered the chance to try out for the White Sox again in 1919, he turned down the opportunity. Baseball still had its hold on hold on Scott though, as he headed west to pitch for the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League.

Joining the team in late May, he won 13 games over the rest of the 1919 season. Scott turned up the next spring with a full beard and a desire for an increase in salary. Seeking to create a publicity stunt, team owner Alfred Putnam promised Scott a $500 bonus–as long as he did not shave. Scott’s whiskers soon became a major media issue, with newspaper editorialists urging him to shave to “set a better example for youth.” The situation even led to a league vote to ban facial hair for PCL players. Scott finally shaved off his beard, and was glad to do so as it had caused an aggravating rash all season long. The beard controversy obscured an excellent season of pitching for Scott, as he won 25 games and recorded a league leading 2.29 ERA.

Scott continued to pitch in the minor leagues for the next seven seasons. From 1921-1924, he won 58 games for a powerhouse Seals team that won league championships in 1922-1923. In 1923, Scott pitched another no-hitter, this time emerging victorious in a 5-0 win over the archrival Oakland Oaks. League officials even relented on their facial hair policy to allow him to wear a mustache. He moved on to the New Orleans Pelicans in the Southern Association from 1925-1927, winning 31 games for two more championship clubs. After the 1927 season, Scott retired as an active player after two decades of successful work on the mound in the major and minor leagues.

Off the field in this period, Scott lived in California during the off-season, doing technical work for Hollywood movie studios on a part-time basis. According to some reports at the time, Scott also spent time as part of a religious cult in the California desert, and as an evangelist. Details are sketchy, but it is likely that Scott was involved with the religious ministries of popular evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, whose Foursquare Gospel mission was based in Los Angeles near Scott’s off-season home. His religious activities notwithstanding, Jim Scott could not stay away from baseball for long. Following retirement, he made the jump from player to umpire, working in the Southern Association in 1928-1929, and then making the jump to the National League for the 1930-1931 seasons.

Scott’s last season of umpiring came in the Southern Association in 1932. Settling permanently with his family in Los Angeles, he began working fulltime for RKO and Republic Studios. Scott served as the “best boy” or chief electrician, working mainly on westerns, and later was promoted to head property man. He continued to travel to Lander annually to hunt and fish with his old friends there. Meanwhile, his son Jim Jr. followed in his father’s baseball footsteps by playing four seasons in the minor leagues prior and after World War II.

Scott continued to work in the motion picture industry until 1953, when he retired shortly after the death of his wife. The always heavy Scott began to experience heart troubles, suffering a heart attack in 1956. Seeking a cure in the desert air, he traveled to Jacumba, California, for a vacation in April, 1957. On the morning of April 7, he suffered a massive heart attack and was found dead in his hotel room by the maid. He was buried next to Hattie in Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California. In 1999, the state of South Dakota honored their native son by electing him to their state’s Hall of Fame.

Note

A different version of this biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

I must first credit the assistance of fellow SABR member David Trombley, who generously shared with me his draft notes, sources, and research on Scott. I used the contents of Scott’s Hall of Fame files and The Sporting News files, which specifically include the following:

Wyoming State Journal:

August 21, 1908

October 21, 1910

October 27, 1911

January 19, 1912

April 26, 1912

July 13, 1917

October 7, 1917

April 21, 1957 (obituary feature)

Chicago Tribune:

April 26, 1908

May 14, 1914

Sacramento Union, 9/28/52 “Those Whiskers Were Grown in Vain” 1952 by Bill Conlin

Lardner, Ring. You Know Me, Al Touchstone Reprint Edition, 1991.

Stein, Irving. The Ginger Kid: The Buck Weaver Story (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992)

www.baseball-reference.com

Total Baseball VI

The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd ed.)

Full Name

James Scott

Born

April 23, 1888 at Deadwood, SD (USA)

Died

April 7, 1957 at Jacumba, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.