Jim Shaw

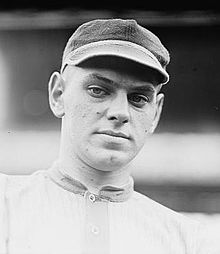

Only 20 years old when the Washington Senators broke camp in spring 1914, right-hander Jim Shaw was deemed a can’t-miss pitching prodigy. The youngster had impressed the previous September during a brief late-season audition with the club, and his spring work had left some onlookers near-swooning, with favorable comparison to renowned staff ace Walter Johnson coming from no-less-informed an observer than Washington manager Clark Griffith. Good-sized (6-feet, 180 pounds) with broad shoulders and noticeably long arms, Shaw bore a striking physical resemblance to Johnson and reputedly threw just as hard, with a nasty, sharp-breaking curve besides. Greatness, it seemed, was destined for Jim Shaw.

Only 20 years old when the Washington Senators broke camp in spring 1914, right-hander Jim Shaw was deemed a can’t-miss pitching prodigy. The youngster had impressed the previous September during a brief late-season audition with the club, and his spring work had left some onlookers near-swooning, with favorable comparison to renowned staff ace Walter Johnson coming from no-less-informed an observer than Washington manager Clark Griffith. Good-sized (6-feet, 180 pounds) with broad shoulders and noticeably long arms, Shaw bore a striking physical resemblance to Johnson and reputedly threw just as hard, with a nasty, sharp-breaking curve besides. Greatness, it seemed, was destined for Jim Shaw.

A century later, any comparison of the long-forgotten Shaw to the immortal Walter Johnson would be ludicrous. Handicapped by chronic control problems, nagging injuries, and an often complacent attitude, Shaw was never able to fully harness his natural talent and proved a disappointment. But he was far from a bust. Despite his shortcomings, Shaw gave the Senators almost a decade of useful service, posting five double-digit-win seasons. At times he even managed to lead American League hurlers in certain secondary pitching statistics, some positive — game appearances (1919); innings pitched (1919), and retroactive saves (1914 and 1919), others not — walks (1914 and 1917) and wild pitches (1919 and 1920). In the end, Jim Shaw was neither phenom nor flop. Rather, the descriptive that perhaps best suits him is: underachiever.

James Aloysius Shaw was born in Pittsburgh on August 13, 1893, the second of four children born to salesman John J. Shaw (1862-1933) and his wife, the former Elizabeth Brown (1863-1916).1 Both parents had been brought to America as toddlers, John from Ireland, his spouse from England, and raised in Pittsburgh where they met, married, and began their family. The Shaws were Catholic, and young Jim began his education at the neighborhood parochial school (St. Mary’s) before matriculating to East Liberty Academy. There, his pitching prowess, first developed on city sandlots, began to attract notice. Jim left school after his sophomore year but continued pitching for local amateur and semipro nines, most notably the Pittsburgh Collegians, a fast independent club.

There are several versions of how Shaw got his start in professional baseball, but the most likely account begins with a 1912 pitching outing with the Collegians observed by Frank Smith, a Pittsburgh native then at the tailend of an 11-season major-league pitching career. Impressed by Shaw’s stuff, Smith asked the teenager if he was interested in turning pro. If so, Smith could secure him a contract with the Montreal Royals of the Double-A minor International League.2 Shaw was definitely interested, but continued pitching for the Collegians while he awaited tender of a contract from Montreal. Umpiring an ensuing Shaw outing against the University of West Virginia varsity was Charlie Hickman, a retired major-league outfielder. Once Shaw had finished with the Mountaineers, Hickman contacted Washington Senators manager Clark Griffith about the budding star whose game he had just called. Hickman’s recommendation was good enough for Griffith, and, wasting no time, he wired Shaw a Washington contract offer that evening, with instructions to report to the Senators spring training camp next March if he signed. He (or more likely his mother) did,3 and, in short order, Shaw was the property of the Senators.

Events had worked out propitiously for Jim Shaw, placing his baseball future in the hands of a pitching past-master. A former hurling stalwart himself, Clark Griffith had used toughness, guile, and a repertoire of tricky offspeed servings to chalk up 237 major-league victories, and there was little he did not know about the art of pitching. And once he actually saw Shaw in action during spring camp, Griffith was enthralled by his size, long arms, fluid overhand throwing motion,4 and electric stuff. He immediately assigned veteran catcher-coach Jack Ryan the task of developing the youngster and reporting back to Griffith daily on Shaw’s progress.5 Like Griffith, Ryan was promptly impressed, submitting nothing but glowing reports to the club boss.6

Much as he prized his new recruit, Griffith appreciated that Shaw was still a raw talent, not yet ready to face major-league batsmen. Griffith therefore optioned him to the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Coal Barons of the Class B New York State League. There, he could gain needed professional experience under the watchful eye of hard-nosed player-manager Joe McCarthy. But Shaw’s time as a charge of the future Hall of Fame field leader proved brief. Within weeks Shaw was returned to Washington, McCarthy expressing a preference for the veteran hurlers on his staff.7 Some 50-plus years later, Shaw revealed that an ill-timed clubhouse laugh after a tough Wilkes-Barre loss was the real cause of his landing in the McCarthy doghouse.8

Shaw still required minor-league seasoning, but Griffith proceeded with caution. Before sending Shaw out again, the Washington skipper consulted with American League President Ban Johnson. But upon receiving official assurance that Washington would retain the rights to Shaw, Griffith optioned him to the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses of the Class B Tri-State League.9 Arriving in late May, Shaw tore up the circuit, mowing down overmatched opposition hitters. In a July 26 outing against Allentown, he set a league record with 14 strikeouts, fanning 10 enemy batters in succession.10 Although his final record was an undistinguished 13-10, Shaw threw repeated high-strikeout games and was the circuit’s dominant pitcher.11

In mid-August, Griffith exercised his option on Shaw, directing the pitcher to report to Washington at the close of the Tri-State League season.12 But Shaw’s performance had not gone unnoticed by other major-league clubs, and soon Griffith found himself fending off rival claimants for the youngster. With attractive offers for Shaw reportedly in hand from the Cleveland Naps ($5,000) and the Detroit Tigers ($3,000), York club boss George Heckert challenged the validity of Washington’s hold on the pitcher, claiming that Shaw was York property.13 After some serious skirmishing between the parties, the National Commission rebuffed Heckert and upheld Washington’s right to Shaw.14 But no sooner had that matter been settled than the St. Louis Browns stirred new controversy by selecting Shaw in the minor-league player draft.15 But this claim, too, was put on the kibosh by the National Commission.

While official proceedings raged about him, Shaw reported for duty with the Senators. He made his major-league debut on September 15, entering in relief of Bob Groom with Washington trailing in the fourth, 5-0. In four innings Shaw walked four. But otherwise, the White Sox could not reach him. He struck out six and allowed only one basehit, a scratch infield single. In his postgame report, veteran sportswriter J. Ed Grillo observed that “there is something about Shaw’s pitching that reminds one of Walter Johnson. He has a free, easy motion, a world of speed, and handled himself like a veteran.”16 Later given a start in an off day exhibition game against the International League champion Newark Indians, Shaw dazzled, striking out 14 in a 2-1 victory. He capped off his late-season audition with another impressive, albeit losing, performance. On October 3, Shaw struck out eight of the second-place Boston Red Sox in eight innings, only to lose, 2-0.

In the wake of such performance, Washington notables seemed intent on outdoing each other in praise of the Senators’ prospect. To the Washington Evening Star’s Grillo, “Shaw cannot fail to make a great pitcher,”17 while fellow Star correspondent Paul W. Eaton likened the newcomer to another Walter Johnson.18 But local scribes were not the only ones high on Shaw. Veteran Washington catchers Jack Ryan and Mike Kahoe maintained that “Shaw is the most promising youngster that they have had contact with,” with Ryan adding that Shaw “had the hardest delivery he has ever handled.”19 Even the normally restrained Griffith waxed effusive, calling Shaw “the best young pitcher he ever saw break into fast company,”20 and saying that as long as “nothing happens to Shaw, he will give Johnson a close race for pitching honors next season.”21

To hasten the progress of a young Washington pitching staff, Shaw and fellow prospects Slim Love, Doc Ayers, Joe Boehling, Harry Harper, and Joe Engel were enrolled in a postseason pitching seminar conducted by Professor Griffith and worked out daily under their manager’s tutelage until late-fall Washington weather became inhospitable.22 As the year 1914 dawned, new voices swelled the chorus of Shaw admirers. Washington Post sportswriter Stanley T. Milliken called him “the most promising youngster on the payroll of the Nationals,”23 while Sporting Life opined that “the sensational young twirler [is] considered certain to develop into a pitching star of the first magnitude.”24 But all would not be smooth sailing for Jim Shaw that season. Finger blisters retarded his throwing in spring camp, but his maiden regular-season start was an impressive one, six innings of three-hit ball in a 14-1 rout of New York. After the game, home-plate umpire Bill Dinneen, a former pitcher himself and the winner of 170 turn-of-the-century major-league games, declared that he had “never seen a more promising pitcher than Shaw in my life. That boy has a lot of stuff and is sure to make one of the greatest pitchers the game has ever produced. To me he looks like a combination of Walter Johnson and Amos Rusie.”25 A month later, Shaw humbled the Yankees again, shutting them out on six hits, 2-0.

Unhappily, Shaw proved unable to keep it going, as he was maddeningly inconsistent, his offseason attendance at the Griffith tutorial notwithstanding. By mid-August, his erstwhile press admirers had grown impatient, with hometown sportswriter Eaton lamenting that Shaw “was badly in need of polishing.”26 The criticism of Ed Grillo was more pointed, assigning Shaw demerits for poor fielding of his position, an inability to hold baserunners, and a lack of pitching savvy.27 And while Grillo remained an admirer of Shaw’s “terrific speed and great curve ball,” he counseled the hurler to “leave his slow ball in the clubhouse.”28 Whether or not Shaw took notice of the Grillo critique is unknown. But before the season was out, he had righted himself, tying the Senators club single-game record for strikeouts: 14 in a two-hit, 1-0 whitewash of his favorite patsies, the New York Yankees.29 Still, his rookie season had been an erratic one. The problem first and foremost with Shaw was his chronic wildness. At season’s end, he led American League hurlers in walks (137), exhibiting a penchant for issuing passes with men already on base. Still, the quality of Shaw’s stuff was undeniable. His 164 strikeouts were fourth behind Walter Johnson’s 225 among American League pitchers, while a .217 opponents’ batting average (third best in the AL) reflected how difficult Shaw was to hit. In all, he made 48 appearances as both a starter and reliever, going 15-17, with a 2.70 ERA in 257 innings-pitched. He also threw five shutouts in his first full season as a major leaguer, leaving even critic Grillo predicting that “the day is not far off when there will be little to choose between Walter Johnson and Jim Shaw.”30

That day would not arrive in 1915, a nightmarish year for the young hurler. He had trouble getting his arm loose from spring camp on, and was used only sparingly until manager Griffith dispatched him to Bonesetter Reese in mid-August.31 But Reese’s chiropractic ministrations failed to cure the suspected misplaced ligament in Shaw’s pitching shoulder and Shaw was shut down completely late in the season.32 In 25 games, he posted a substandard 6-11 record, but had a respectable 2.50 ERA in 133 innings pitched. That fall, however, the letdown of the 1915 season was displaced by far graver concern for Shaw’s life and future well-being.

An inexperienced outdoorsman, Shaw had accompanied friends on a mid-November rabbit-hunting expedition in fields outside Pittsburgh. As he investigated a rock pile with the stock-end of a 12-gauge shotgun, the weapon discharged from point-blank range, its load striking Shaw in the jaw and throat. Miraculously, Shaw survived the blast but was in dire condition by the time he arrived at St. Francis Hospital.33 At first, doctors were not optimistic about Shaw’s chances, but were heartened when x-rays showed that their patient’s windpipe and spinal column were undamaged. His youth and excellent physical condition also worked in Shaw’s favor. Against the odds, Shaw’s condition responded to treatment and he slowly recovered. But he would carry shotgun pellets in his neck for the remainder of his life.

In time, one happy byproduct of Shaw’s hospital stay effected a change in his domestic situation. Among his bedside attendants was a young nurse named Anne Marie Franey. Sometime after Jim’s discharge, he and his nurse began dating. They married after the 1916 season and eventually had four children: Jane (born 1918), James Jr. (1919), Leo (1922), and Howard (1926).

Although sometimes bothered by a stiff neck, Shaw was on hand and participated in squad workouts when the Senators opened their 1916 spring camp. Early reports regarding his work were encouraging, but once the regular season began, Shaw saw only sparse action and was not particularly effective. In 26 games, he went 3-8, with a 2.62 ERA in 106⅓ innings pitched. Still, manager Griffith remained hopeful that Shaw would yet realize his potential and re-signed him for the 1917 campaign.34

Only 23 when the season began, Shaw finally began to reward Griffith for his patience. His outings remained inconsistent, but at long last, the good ones outnumbered the bad. And when he was on, Shaw could still dominate, as attested by the no-hitter he took into the ninth inning against Detroit late in the season.35 On October 4, a season-ending 5-4 victory over Boston pushed Shaw’s record to 15-14, giving him his first winning major-league campaign. That final-day triumph also gave Shaw the 15 wins he needed to collect a nice $300 contract bonus.36 A league-leading 123 walks surrendered, however, reflected a continued need for Shaw to work on his control.

By the time the 1918 season commenced, the manpower demands of American entry into World War I were beginning to be felt by major-league ballclubs. But as a married man, Shaw was assigned a 4A military draft classification and was, consequently, an unlikely target for conscription.37 Pitching for a competitive (72-56) Washington club, Shaw got off slowly but closed with a rush. After he won 13 of his last 15 decisions, his record stood at 16-12 when the season came to a prescribed early end on September 2, 1918. Shaw ranked second among AL pitching leaders in strikeouts (129, to Johnson’s 162), and fourth in game appearances (41). And only 90 walks in 241⅓ innings pitched showed noteworthy improvement in Shaw’s command.

Given the early-September conclusion of the major-league schedule, Shaw, like many others, extended his season by playing in semipro and industrial leagues. On Sundays he pitched for the St. Andrew’s Athletic Club in Baltimore,38 while weekdays were spent working/playing for the Lebanon (Pennsylvania) Furnace Company nine in the Bethlehem Steel Company League.39 The following spring, Shaw, a perennial contract holdout, attempted to leverage a reputed offer for the 1919 season from Lebanon Furnace into a higher wage from Washington. But the post-WWI disbanding of the steel-company league thwarted that stratagem.40 Nevertheless, Shaw managed to wheedle a handsome two-year/$6,000-per-season deal out of the famously parsimonious Griffith.41

Griffith’s money appeared well-invested when Shaw got off to a fast start in 1919. By now, Shaw had expanded his hurling arsenal to include a shineball-like pitch that he called a “sailer.”42 Although toiling for a bad club – the Senators would finish the season in seventh place with a barely .400 (56-84) record – a 1-0 whitewash of St. Louis on July 30 boosted Shaw’s personal log to an admirable 15-8. But from there, his numbers spiraled sharply downward. Nine losses in his final 11 decisions leveled Shaw’s record to 17-17 at season’s end. Still, he led American League hurlers in game appearances (45), innings pitched (306⅔, tied with Chicago’s Eddie Cicotte), batters faced (1,231), and retroactive saves (5, tied with two others). He also placed second to Johnson (145) in strikeouts recorded (128).

Working on the second year of his contract, Shaw’s 1920 record (11-18, .379) was as poor as, indeed worse than, that of the sixth-place (68-84, .447) Senators club that he pitched for. Perhaps suffering from the newly imposed major-league ban on trick pitches like his sailer, Shaw got off to a 0-4 start and did not post a victory until June 20. Like most pitchers that season, the suddenly superheated offenses that marked the end of the Deadball Era inflated his year-end numbers, but even still, his 4.27 ERA was high. And for the second consecutive year, Shaw led the AL in wild pitches (13).43 In all, he had taken a major step backward and, while still relatively young (27), the chances of his ever fulfilling the potential of his earlier years were now fading. But ever hopeful, Griffith signed Shaw for a 1921 tour of duty.

As the new season approached, Washington Evening Star sportswriter Denman Thompson, never much of a Shaw fan to begin with, offered a dismissive assessment of the hurler: “It has been recognized for years that Shaw is sufficiently endowed with natural physical attributes to make him one of the greatest pitchers in the business, but he never was and never will be. … With Shaw, it is not a case of bad habits, late hours or anything of that sort. Around the hotel lobbies he is as full of ginger as any of the athletes, but as soon as he gets into a uniform he loses all his pep and just goes dead. Jim is suspected of being plain lazy.”44 Denman was not the first scribe to accuse the amiable Shaw of lacking competitive fire, and every spring there were always pounds that Shaw – a formidable trencherman – needed to shed. But now, his hurling was hampered by a new problem: a knee injury that compromised his pitching stride.45

Club boss Griffith turned over the managerial reins to retired infielder George McBride for the 1921 season, but Shaw proved of little use to his new skipper. The knee problem limited his availability and Shaw was hit hard when he pitched. On July 21, an ineffective inning of relief work (four runs allowed) against the White Sox brought the major-league pitching career of Jim Shaw to a close.46 Before the season was out, he was sold to the New Haven Indians of the Class A Eastern League.47

In nine major-league seasons, Shaw had gone 84-98 (.462) on Washington teams that had played break-even baseball.48 In 1,600⅓ innings pitched, he had allowed only 1,466 hits (.247 OBA) and posted a 3.07 ERA with 17 shutouts. But 712 walks/hit-batsmen (as opposed to 767 strikeouts) had placed Shaw in frequent hot water and too often led to his defeat. Blessed with outstanding stuff, Shaw never matured into the hurling star predicted at the beginning of almost every season of his major-league tenure. In the end, an inability to throw strikes consistently, nagging injuries, and a lack of ambition combined to make Jim Shaw an underachiever.

Over the winter, surgery was performed on Shaw’s ailing knee,49 and while the majors were through with him, there was no shortage of high minor-league clubs interested in the stillonly 28-year-old pitcher. Sold by Washington (which had reclaimed Shaw from New Haven in the offseason) to the Seattle Indians of the Double-A Pacific Coast League, great things were expected of Shaw. Seattle club boss Walter McCredie forecast him “to win at least twenty games … if the knee regains its strength.” But Shaw and his new employer were immediately at loggerheads over money, with Shaw demanding a major-league-level wage that McCredie was unwilling to pay. After several weeks’ fruitless negotiation, McCredie rescinded the purchase of the hurler’s contract “and told Shaw to stay in Washington.”50 Shaw got a final comeback chance when another Double-A club, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, decided to purchase him. Like McCredie, Minneapolis club boss Joe Cantillon was optimistic about Shaw, predicting that “he will win more games than any other pitcher on the Minneapolis club.”51But surgery had not cured Shaw’s debilitating knee problem, and after he got only one hitter out in a May 22 start against Milwaukee, the Millers released him.52

His professional career over, Shaw stayed connected to the game by managing (and occasionally pitching) for his new hometown’s semipro club, the Cherrydale (Virginia) Athletic Club. But needing to support a young and growing family, he became a federal government employee, eventually spending more than 30 years as an agent with the alcohol-tax unit in the US Treasury Department. Shaw was an active member of the Knights of Columbus at the local parish (St. Agnes) where the family attended church, and he reconnected with old teammates at the annual winter banquet of the Washington Home Plate Club and at Senators’ old-timer’s games. Apart from the untimely death of 16-year-old son Leo in 1938, post-baseball life went well for Jim Shaw.

Shaw was among the hospital room visitors as the end drew near for his old boss and friend Clark Griffith in October 1955. Four years later, the passing of wife Anne Marie Shaw brought a happy 43-year marriage to an end. Soon thereafter, Jim’s health went into noticeable decline. He had long been afflicted with heart disease, and other vital organs began to lose function, as well. In early 1962, he was admitted to Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, and died there of multiple complications from heart, kidney, and liver failure on January 27. James Aloysius Shaw was 68. After a Requiem Mass at St. Agnes Church, his remains were interred next to those of his wife and son Leo at St. Mary Cemetery in Alexandria, Virginia. Survivors included daughter Jane, sons Jim and Howard, and nine grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided herein include the Jim Shaw file with questionnaire maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census data and Shaw family posts accessed via Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Jim’s siblings were Lillian (born 1888), Elinor (1896), and John H. (1899).

2 As per sportswriter Stanley T. Milligan in the Washington Post, March 8, 1914.

3 Ibid. Because Shaw was too young to sign a legally binding contract, one of his parents had to sign the pact with Washington for him. The following season, Elizabeth Shaw signed for her still-underage son. See the Washington Evening Star, June 2, 1914.

4 Wikipedia and other modern references maintain that Shaw was nicknamed “Grunting Jim”because the exertion attending his throwing of a pitch produced a grunt that could be heard in the grandstand. In a circa 1960 player questionnaire, Shaw himself acknowledged the nickname but the writer’s review of reportage of Shaw’s Washington pitching career encountered only one contemporaneous Grunting Jimnewspaper reference.

5 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, April 2, 1913, and Sporting Life, April 6, 1913.

6 As noted in the Washington Evening Star, April 2 and 11, 1913.

7 As per Sporting Life, June 21, 1913.

8 See Francis Stann, “Good While It Lasted,” Washington Evening Star, August 27, 1959.

9 Johnson had advised Griffith that the option of Shaw to York would be protected by application of Washington’s original option agreement with Wilkes-Barre, as per sportswriter Paul W. Eaton in Sporting Life, August 30, 1913.

10 As reported in Sporting Life, August 2, 1913.

11 Meanwhile back in Wilkes-Barre, manager McCarthy was reportedly “kicking himself in the vital spots for letting out Jimmy Shaw, the clever pitcher who went down and proceeded to burn up the Tri-State League.” Sporting Life, September 13, 1913.

12 As memorialized in National Commission Bulletin 863, issued August 13, 1913, and published in Sporting Life, August 23, 1913. See also the Philadelphia Inquirer, August 17, 1913.

13 As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times, August 23, 1913, and Sporting Life, August 30, 1913.

14 As reported in the Washington Evening Star and Washington Post, August 29, 1913. Instead of thousands from Cleveland or Detroit, Heckert received the standard $300 when Washington exercised its option on Shaw.

15 As reported in the Washington Evening Star and Washington Post, September 16, 1913, and Sporting Life, September 20, 1913.

16Washington Evening Star, September 16, 1913.

17 Ibid.

18 See Sporting Life, November 18, 1913.

19Washington Evening Star, October 16, 1913; Sporting Life, November 18, 1913.

20Washington Evening Star, September 29, 1913.

21Washington Evening Star, October 16, 1913; Sporting Life, November 18, 1913.

22 See Sporting Life, October 18, 1913.

23Washington Post, January 6, 1914.

24Sporting Life, January 17, 1914.

25Washington Evening Star, May 6, 1914. Dinneen was particularly impressed by Shaw’s curveball.

26 See Sporting Life, August 22, 1914.

27 See the Washington Evening Star, August 16, 1914.

28 See the Washington Evening Star, September 1, 1914.

29 Walter Johnson had established the club mark with a 14-strikeout game in 1910, and would later duplicate that feat during the 1924 season. But thereafter, the Johnson-Shaw standard would endure for decades, unsurpassed until curveball master Camilio Pascual struck out 15 Boston Red Sox batters in an April 1960 game.

30 Per Sporting Life, April 10, 1915.

31 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, August 20, 1915.

32 As per the Washington Evening Star, September 19, 1915.

33 Complete accounts of the hunting incident and its aftermath were published in the Washington Evening Star and Washington Post, December 12, 1915.

34 As reported in Sporting Life, November 18, 1916.

35 The no-hitter bid was broken up by a Ty Cobb single, and Shaw finished with a two-hit, 2-0 victory.

36 Oddly, neither Shaw nor manager Griffith seemed to appreciate that Shaw had won 15 games – and had thus been entitled to the bonus – until AL President Ban Johnson promulgated the official statistics for the 1917 season the following March. See the Pueblo (Colorado) Chieftain, March 5, 1918, and (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, March 18, 1918.

37 Staff ace Walter Johnson was also classified 4A. In the end, the only regular that the Senators lost to the military was future Hall of Fame outfielder Sam Rice.

38 As reported in the Baltimore American, September 13 and 15, 1918.

39 Per the Washington Evening Star, August 18, 1918, Washington Post, August 21, 1918, and Baltimore American, September 29, 1918.

40 See the Baltimore Sun and Canton (Ohio) Repository, March 8, 1919, and Washington Evening Star, March 16, 1919.

41 As reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer, March 26, 1919.

42 As noted in the Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, June 19, 1919, Evansville (Indiana) Courier, June 22, 1919, and Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 15, 1919.

43 Shaw had thrown a league-leading 10 wild pitches the season before.

44Washington Evening Star, April 3, 1921.

45 The circumstances of Shaw’s knee injury were undiscovered by the writer but in a late-life interview, Shaw maintained that the knee problem stemmed from a spine injury he had suffered during childhood and gradually aggravated by pitching. See Spann, Washington Evening Star, August 27, 1959.

46 Shaw’s final appearance in Washington livery came August 11 in an exhibition game against the Richmond Colts of the Class B Virginia League, as per the Washington Evening Star, August 13, 1921.

47 As reported in the Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald and Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, September 6, 1921, and (Portland) Oregonian, September 7, 1921. The transaction was actually more of a late-season loan, as the rights to Shaw reverted to Washington upon the completion of the New Haven schedule.

48 The Washington Senators’ record for Shaw’s eight complete seasons with the club (1914-1921) was a cumulative 592-594 (.499).

49 As subsequently reported in the Lexington (Kentucky) Leader, February 4, 1922, Jackson (Michigan) Patriot, February 6, 1922, and Charlotte Observer, February 13, 1922.

50 As per the Oregonian, February 17, 1922.

51 As per the Milwaukee Sentinel-Journal, February 23, 1922.

52 As reported in the Milwaukee Sentinel-Journal, May 23, 1922, and Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune and Grand Forks Herald, June 17, 1952.

Full Name

James Aloysius Shaw

Born

August 19, 1893 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

January 27, 1962 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.