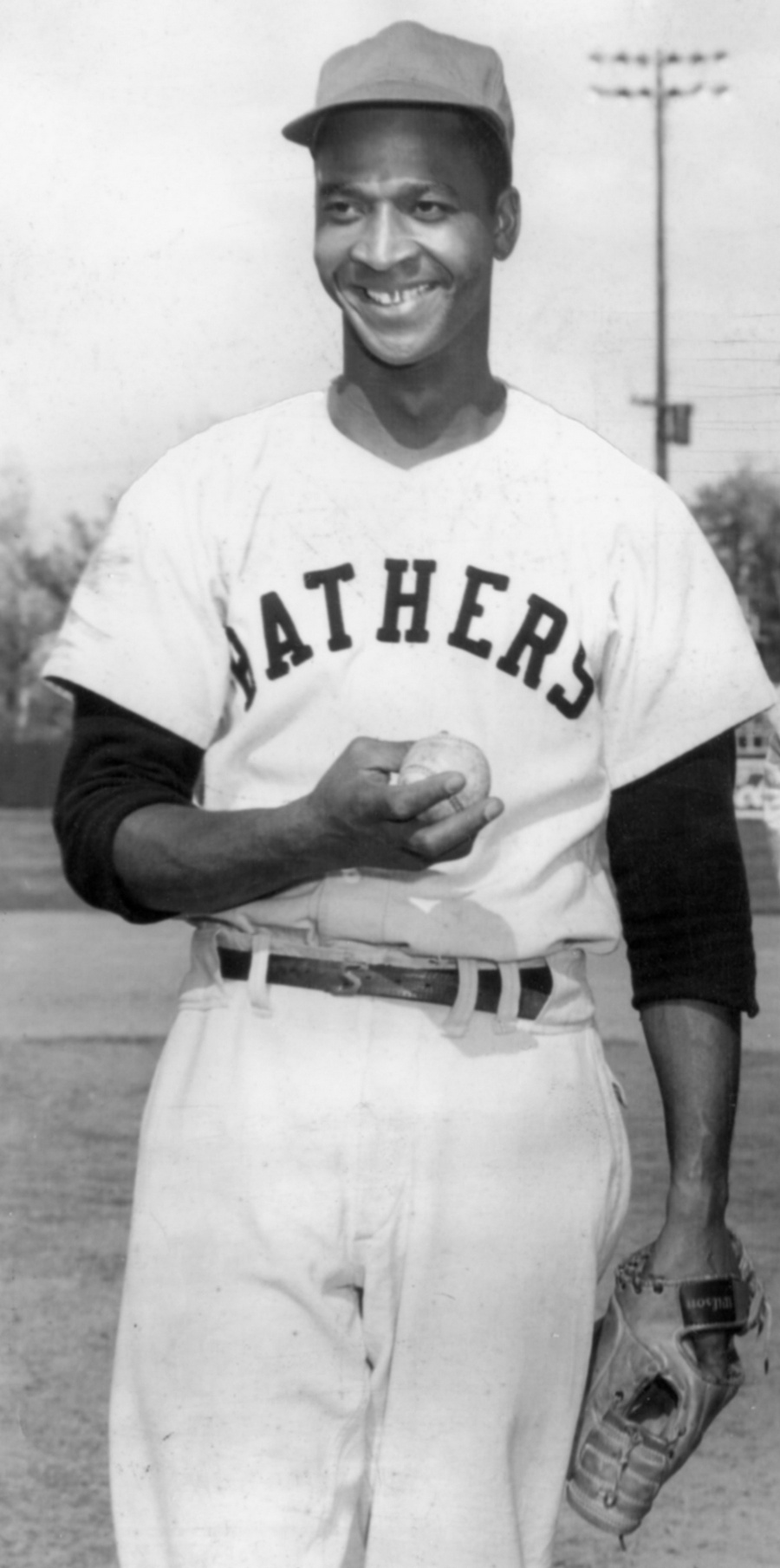

Jim Tugerson

While Jackie Robinson and some of the other pioneers who helped break the odious color barrier now receive credit for their accomplishments, others who showed just as much courage have been forgotten. Jim Tugerson is one such player.

While Jackie Robinson and some of the other pioneers who helped break the odious color barrier now receive credit for their accomplishments, others who showed just as much courage have been forgotten. Jim Tugerson is one such player.

Tugerson was born in Florence Villa, Polk County, Florida on March 7, 1923, and christened James Clerence — at least that is how his middle name is spelled on his Florida death record, though it may be a mistake. He dropped out of school after grammar school and received training as a surveyor. On January 26, 1943, he enlisted in World War II and served in the Army Air Force as a military policeman.

In 1950, Jim’s younger brother Leander, also a World War II veteran, signed to pitch for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. The Clowns were the Black touring team that was best known for mixing baseball with comedy, although they had scaled back the entertainment aspect in order to gain admittance to the Negro American League. Leander experienced a successful season as the Clowns captured the Negro American League’s eastern title and he convinced Jim to join him in 1951.

With the help of the two brothers, the Clowns won both the first and second-half titles in 1951. Jim, a lanky 6-foot-4, 194-pound right-hander, posted a 10-5 mark in his first year of professional ball. Leander was the big star, however, compiling a 15-4 record that included a no-hitter at Birmingham on August 22 in which he struck out sixteen.1

Following this standout performance, it was expected that Leander would be signed by a major league club, and he did indeed sign with the White Sox, who intended to have him play at Colorado Springs in 1952. But eventually he was returned to the Clowns, so the brothers spent their second straight season with the Clowns and (along with a new teammate named Henry Aaron) again won the first-half title.2 After posting an 8-2 mark for the Clowns, Jim Tugerson ended the year with Oriente of the Dominican Summer League.

The Tugerson brothers finally joined organized baseball for the 1953 season, but the club they signed with was less than ideal. Slowly but surely, the minor leagues were being integrated, but there was still plenty of resistance, especially in the Deep South. This made the Tugersons’ decision to sign with the Hot Springs Bathers of the Cotton States League — a Class C league made up of four teams in Mississippi, three in Arkansas and one in Louisiana — a fateful one.

Their signing met with immediate resistance. On April 1, 1953, Mississippi Attorney General J.P. Coleman announced that integrated clubs did not have the right to appear on baseball diamonds in his state. Coleman acknowledged that there was no specific statute to that effect, but based his edict upon the emphasis placed on segregation in the Mississippi constitution.

Management of the Bathers apparently offered a compromise at this point, pledging to use the Tugersons primarily in home games, pitching them in road games only with the opponents’ permission. Despite the offer, the league’s other seven teams held a closed-door meeting on April 6, and then President Al Haraway announced that Hot Springs had been ousted from the Cotton States League. Haraway cited Article 5, Paragraph 13 and 14 of the league constitution, by which two-thirds of clubs can vote to dismiss a club that “prevents the league from functioning properly” and claimed: “Since the Hot Springs club has assumed a position from which it refused to recede, which would disrupt the Cotton States League and cause its dissolution, which position having been assumed without the courtesy of a league discussion, and since it is a matter of survival of the league, or transfer of the Hot Springs franchise, this action is taken.”

The decision immediately came under fire, both for its rank bigotry and because the secret meeting had blatantly contravened the league’s constitution. Leslie M. O’Connor, former assistant to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis and now a member of the Major-Minor Executive Council, pointed out that the Cotton States League constitution provided any club facing dismissal with the opportunity to be notified in writing and reply to the charges before a vote was taken. Not only did this not happen, but there were also rumors that only five clubs had voted to expel Hot Springs, which was shy of the two-thirds requirement. Of course nobody knew for certain because of the secrecy surrounding the league’s proceedings.3

So National Association President George M. Trautman stepped in and ordered that Hot Springs remain in the league until he had time to review the matter. With this hanging over their heads, the league owners held another secret meeting on April 14 and voted to readmit the Bathers. There were rumors that some sort of compromise regarding the Tugersons had been agreed upon, but nobody was talking as there were threats of a $1,000 fine to anyone who disclosed what had transpired at the meeting.

The league’s about-face gave Trautman the chance to avoid a controversial issue, but to his credit he did not do so. The next day he announced that the action taken on April 6 was illegal flouting of the league’s constitution. But he did not stop there, stating that even if procedures had been followed correctly, that if the only reason for banishment was “the employment of two Negro players, this office would still be required to declare the forfeiture invalid. The employment of Negro players has never been, nor is now, prohibited by any provision of the Major-Minor League Agreement.”4

While all this was happening, the Hot Springs’ players were watching in enforced idleness. With the April 21 opener approaching, the team had played only a single exhibition game as their futures were being debated in the national press. It must have been especially frustrating for the Tugersons, but they kept their poise. Commenting on behalf of Leander and himself, Jim Tugerson said, “We hope this is not embarrassing to the city of Hot Springs, which has been so nice to us. We don’t wish to keep the city from having baseball. But as long as the club wants us, we will stay here and fight.”5

Then on the eve of the season, both brothers were suddenly optioned to Knoxville of the Class D Mountain States League. Hot Springs Secretary W.D. Rodenberry issued a puzzling statement indicating that the team didn’t “want to embarrass the sport of baseball, the colored players or any other players or managers by giving the Tugerson brothers an opportunity to prove their ability in the Cotton States League.” He added that on April 7 the brothers had asked to be transferred if their presence would mean the end of the league, as many feared.

Under the circumstances, the timing of the announcement seemed very suspicious. Rodenberry’s comments left little doubt that the move was made under pressure, as he suggested that newspapers in league towns poll their readers to try to get the other owners to reconsider. The decision must have been especially disheartening to Jim Tugerson, who had recently turned 30 and must have seen the demotion as a crushing blow to any chance of reaching the White major leagues. But he again took the high road, thanking the Bathers, saying that he and his brother had no hard feelings toward anyone, and expressing hope that “some day we might be able to return.”6

After being optioned to Knoxville, the two brothers combined to help the Smokies sweep a May 3 doubleheader. Jim pitched and won the opener, and then Leander took the mound for the nightcap. Clinging to a lead but clearly struggling, Leander was relieved by Jim, who even used his younger brother’s glove as he saved the game for him.7

Sadly, that was one of the last times that the two brothers would share a special moment on the baseball diamond. Leander Tugerson developed a sore arm and tried to pitch through it without success. In June, having won only three games for Knoxville, a physician advised him to go home and gave the arm a rest for the remainder of the season.8 It was, as far as I can tell, the end of his once-promising pitching career.

Jim Tugerson, however, blossomed into the league’s best pitcher. After recording six victories in the first four weeks of the season, he was recalled to Hot Springs to start a May 20 game against Jackson, Mississippi. While the move stirred the flames of racial intolerance, race was not the only factor involved. Injuries had reduced the Bathers’ pitching staff to only four men, so team co-owner Lewis Goltz claimed that he was forced to recall Tugerson. In addition, suffering from low attendance, the team desperately needed the large crowd that could be expected to come out to watch the league’s color barrier broken.

Jim Tugerson, however, blossomed into the league’s best pitcher. After recording six victories in the first four weeks of the season, he was recalled to Hot Springs to start a May 20 game against Jackson, Mississippi. While the move stirred the flames of racial intolerance, race was not the only factor involved. Injuries had reduced the Bathers’ pitching staff to only four men, so team co-owner Lewis Goltz claimed that he was forced to recall Tugerson. In addition, suffering from low attendance, the team desperately needed the large crowd that could be expected to come out to watch the league’s color barrier broken.

A large crowd did indeed turn out for the game. But as Tugerson threw his warm-up pitches, a telegram was received from league president Haraway stating that the use of Tugerson violated the agreement reached on April 14 and ordering home plate umpire Thomas McDermott to forfeit the game to Jackson. In vain, the crowd booed the announcement and loudly cheered Tugerson. Goltz must have been even more disappointed, as he was forced to refund the tickets of more than 1,500 fans and turn away many more who “were standing outside and crying to get in.”

Goltz angrily telegraphed Haraway: “The Trautman ruling of April 15 decided it is club’s decision to make on hiring of eligible negro players. Exception is taken to your illegal order. If game is forfeited as threatened the case will be appealed immediately and suit instigated.” Haraway replied: “It is an intra-club matter. Take whatever action you see fit.” Goltz did again appeal to Trautman, but he backed down and returned Tugerson to Knoxville. While his club still retained the right to recall the pitcher on 24-hour notice, his comments suggested that he would not attempt to play Tugerson again.

Jim Tugerson must have been bitterly disappointed at this latest setback, but he once again showed great restraint in commenting, “I am the property of the Hot Springs baseball club. The club called me back. I didn’t ask to come.” He did, however, drop a hint that rocked the baseball world, telling a reporter, “It’s just possible that I may sue [Haraway]. I’m not bitter, but I think he did the wrong thing in making Hot Springs forfeit that game. I hope I land in the majors some day. I want to be in a league where they will let me play ball.” Tugerson’s threat made news all across the country.9

George Trautman wasted little time reviewing the latest debacle and ruling that Haraway had again overstepped his authority. He ordered the forfeited game replayed and accused the Cotton States League of being “at war with the concept that the national pastime offers equal opportunity to all.” The decision prompted Hot Springs club attorney Henry Britt to express pleasure and state that there was a “probability” that Tugerson would again be recalled to Hot Springs.10

So Jim Tugerson returned to Knoxville and continued to add to his league-leading win total and bide his time. There at least he received sympathy and support, with management staging a “Jim Tugerson Night” on June 5 at which African-American fans were admitted free of charge.

But as the weeks went by, it became increasingly clear that he was never going to have the chance to pitch in the Cotton States League. Haraway and the other league owners remained adamantly opposed to integration, with Haraway later claiming implausibly that he had received some 300 letters on the subject and only three of them favored the pitcher.11 Even Britt finally admitted that he was hoping to end the controversy by selling Tugerson to a major league team, explaining, “The league does not want a Negro to play ball, so we are going to sell him in order to keep the league from breaking up.”

Yet being forced to pitch in a Class D loop made that solution far less likely. When former Pirates manager Bill Meyer scouted “Big Jim” he reported that he, “couldn’t tell much … he didn’t have much opposition and he just loafed along. I want to catch him in a game where he has to bear down.”

Finally, in mid-July, Jim Tugerson’s seemingly endless patience ran out. After winning his twentieth game, on the advice of attorney James W. Chestnut, he left the Smokies long enough to travel to Hot Springs and file a lawsuit against the Cotton States League, Al Haraway, and several of the league officials who had prevented him from playing in the circuit. The lawsuit asked for $50,000 on the grounds that the defendants had breached his contract and violated his civil rights by preventing him from following “his lawful occupation of a baseball player” and enjoying the “equal protection of the law in his privileges as a citizen of the United States of America.”12

As soon as he had filed the historic legal action, Tugerson returned to Knoxville and reaffirmed his status as the best pitcher in the Mountain States League with a three-hit shutout in his first game back. He finished the year with a league-leading 29 wins against only 11 defeats and also posted a circuit-best 286 strikeouts in 330 innings. Then he topped that off with four wins in the Shaughnessy playoffs to lead the Smokies to the championship.

After the season, Tugerson barnstormed with a Negro League all-star team and the tour finally gave him the long-awaited chance to pitch in Hot Springs on September 25. It proved a triumphant return, as he beat his onetime Indianapolis Clowns teammates 14-1 in front of 1,200 fans and even hit a home run.13

Two weeks earlier, he had received much less welcome news when circuit judge John Miller tossed out the civil rights part of Tugerson’s lawsuit.14 Miller reserved judgment on the breach of contract claim but before he could rule a compromise was reached. The right-hander’s contract was sold to Dallas of the Texas League and, having received the opportunity he had sought, Tugerson dropped his lawsuit.15

Dallas represented an ideal situation for Jim Tugerson, as the league had integrated in 1952 and he would have an African-American teammate in Pat Scantlebury. But after winning his first game for Dallas, Tugerson struggled and he was sent down to Artesia, New Mexico, of the Class C Longhorn League.16

On top of the discouragement he must have felt, Tugerson was entering a league that was strongly skewed to hitters. Roswell slugger Joe Bauman would swat 72 home runs that season, a minor-league record that still stands, and none of the pitchers who spent enough time in the league to qualify for the title posted an earned run average below 3.60. Tugerson, however, was unhittable, tossing forty-four consecutive shutout innings and chalking up a 9-1 record before being recalled to Dallas.17

Tugerson was less dominant upon his return to Dallas, but by late July he boasted a 7-4 record. Then his luck took a turn for the worse, and he lost six straight games, during which his teammates provided him with only five runs. He ended the year with a 9-14 mark for Dallas, but his 3.98 ERA (in a league where the leader’s ERA was 2.89) suggested that he pitched reasonably well.

The 1954 season also saw the Cotton States League finally integrate. When Hot Springs expressed interest in signing two African-Americans, new league president Emmet Harty polled all five other owners and heard no objections. On July 20, 18-year-old outfielder Uvoyd Reynolds from Langston High School in Hot Springs joined the Bathers and was followed the next day by first baseman Howard Scott of the Negro American League. The team, which had been averaging less than 350 fans per game, drew more than double that total for the first two games.18

Jim Tugerson returned to Dallas in 1955 and spent the whole season there. He posted a 9-12 record, but his 3.19 earned run average suggests that he again pitched better than his won-loss record indicates. Otherwise it was a successful campaign as Dallas captured the regular season title before bowing out in the first round of the Shaughnessy playoffs. Tugerson had two young teammates of color, Ozzie Virgil and Bill White, both of whom were destined for long major league careers.

He played professional ball in Panama that winter and started 1956 in Dallas, but did not stay there long. Shortly after a May 18 start in which he failed to retire a batter, Tugerson was optioned to Amarillo of Class A Western League, where he spent the rest of the season. Being in the Western League gave Jim Tugerson the chance to watch Dick Stuart take a run at Joe Bauman’s home run record (he ended with 66) and to play on his second-straight pennant winner.

Otherwise, however, it was a disheartening season. Somehow he managed an 11-6 record with Amarillo, but his 5.67 earned run average shows that, for a change, he was the beneficiary of good run support. His struggles in 1956 suggest that he may have been experiencing arm trouble, but whatever the reason, one thing was now crystal clear. Now 33 and having failed to pitch well even after a demotion, Tugerson’s window of opportunity for reaching the major leagues was closing.

At season’s end Dallas reacquired his contract, and he again pitched in Panama that winter.19 Before the 1957 season could start, Jim Tugerson announced his retirement.

After staying out of baseball for the year, Tugerson made a spectacular comeback with Dallas in 1958. Now using a sidearm delivery, he led the Texas League with 199 strikeouts while posting a 14-13 record and a fine 3.33 earned run average.20

Dallas joined the American Association in 1959, and Tugerson went with them, meaning that at 36, he was suddenly one rung away from the major leagues. But he battled injuries, and when he was healthy his old trouble with run support recurred, as indicated by his ugly 5-12 won-lost record alongside his respectable 3.51 earned run average. After the year his contract was assigned to Sioux City and then reacquired by Dallas, but at that point Tugerson finally decided to retire for good.21

Both of the Tugerson brothers returned to Florida, and little is known about their lives after baseball. Leander Tugerson died in Alachua County in January of 1965. He was only 37 years of age. Jim died in his native Polk County on April 7, 1983, one month after his sixtieth birthday.

Both of the Tugerson brothers returned to Florida after their baseball careers. Little is known about the later life of Leander Tugerson, who was only thirty-seven when he died in Alachua County in January of 1965.

Jim Tugerson had joined the police force in Winter Haven, Florida, in 1957, becoming its second African-American officer (and receiving leaves of absence in 1958 and 1959 to resume his baseball career). He spent more than a quarter-century on the Winter Haven police force and earned promotion to the rank of lieutenant. He also coached local youth baseball and it was while coaching a youth team on April 7, 1983, that he suffered a fatal heart attack. In recognition of his long service to Winter Haven, the city council passed a resolution to rename the baseball field in his honor.

Was Jim Tugerson deprived of a major league career by bigotry? The evidence does not enable us to say with any degree of certainty. He undoubtedly had fewer opportunities than a White man would have had, and it is quite possible that an earlier start in baseball, better timing, or avoiding arm trouble would have enabled him to reach the major leagues. Yet he did have opportunities to prove himself worthy of advancement and failed to do so, meaning that it is quite possible that he had the talent to excel in the minor leagues but not at the major-league level.

We can be much more confident in asserting that both Tugersons showed great courage in pursuing their dreams of careers in baseball. Jackie Robinson is rightly remembered for his great talent and his great ability. But men like the Tugersons deserve to be remembered because they fought just as courageously to reach the White major leagues, even though they never achieved that goal.

Sources

Contemporary newspaper, sporting presses, censuses, military and vital records; Alan J. Pollock (edited by James A. Riley), Barnstorming to Heaven: Syd Pollock and His Great Black Teams (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006); Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Dick Clark and Larry Lester, editors, The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland: SABR, 1994). Special thanks to John J. Watkins for information on Jim Tugerson’s life after baseball.

With special thanks to Dick Clark.

Notes

1 The Sporting News, September 5, 1951.

2 The Sporting News, May 7, 1952.

3 “Hot Springs Ouster for Using Negroes Halted by Trautman,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1953, 24.

4 “Cotton States and Trautman Revoke Hot Springs Ouster,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1953, 17.

5 Harold Harris, “Cotton Loop Rocked Again; Jim Tugerson Sues for Fifty Grand,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1953, 13.

6 “Hot Springs Options Negro Pair to End Cotton States Controversy,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1953, 28.

7 The Sporting News, May 13, 1953.

8 The Sporting News, June 17, 1953, 36.

9 Valley Morning Star (Harlingen, Texas), May 22, 1953; Emmett Maum, “Forfeit Over Use of Negro Revives Hot Springs Row,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1953, 13.

10 The New Mexican (Santa Fe), June 7, 1953, UP; The Sporting News, June 17, 1953, 36.

11 The Sporting News, October 28, 1953, 10.

12 Bradford (Pennsylvania) Era, July 22, 1953, AP; Harold Harris, “Cotton Loop Rocked Again; Jim Tugerson Sues for Fifty Grand,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1953, 13.

13 The Sporting News, October 7, 1953, 30.

14 Modesto Bee and News-Herald, September 12, 1953.

15 Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, December 8, 1953; The Sporting News, December 23, 1953.

16 The Sporting News, April 14, 1954, 38.

17 Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman, May 25, 1954; The Sporting News, June 2, 1954.

18 The Sporting News, July 28, 1954, 40.

19 The Sporting News, October 10, 1956.

20 The Sporting News, April 9, 1958.

21 The Sporting News, December 23, 1959.

Full Name

James Clarence Tugerson

Born

March 7, 1923 at Florence Villa, FL (US)

Died

April 7, 1983 at Winter Haven, FL (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.