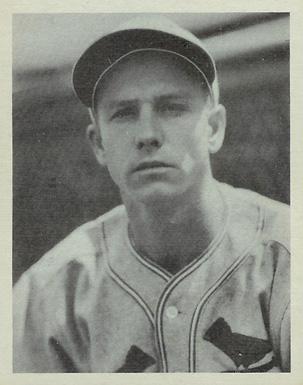

Jimmy Brown

Nineteen forty-five was the happiest year in American history. The end of World War II brought millions of Johnnies and Joans marching home. Families were reunited.

Nineteen forty-five was the happiest year in American history. The end of World War II brought millions of Johnnies and Joans marching home. Families were reunited.

The high barely lasted past Christmas. Nineteen forty-six brought inflation, store shelves bare of many basic consumer goods, and a severe housing shortage. The result was an unprecedented epidemic of strikes that hit nearly every major industry.

The upheaval spread to baseball in a double-barreled dose of labor strife. Recruiters from the “outlaw” Mexican League enticed US players with stacks of cash, and the first effort to organize a true ballplayers union alarmed club owners. Two veteran players were credited with stopping the union drive. Commissioner Happy Chandler said later, “Rip Sewell, Jimmy Brown, and a man from my office beat the union.”1

Long before that, Cardinals owner Sam Breadon praised Brown as “a true-blue gas-houser.”2 There’s no other way to say it: Brown was a scrappy player. When he was failing in the minors, he taught himself to switch-hit and became a .300 hitter in the majors. In seven years with the Cardinals, he played regularly at second base, third base, and shortstop. That versatility was his meal ticket and his curse. With the Cardinals’ deep farm system, he had to fight some phenom for a job nearly every spring.

James Roberson Brown was one of nine children of Archie Brown and the former Dare Roberson, born at Jamesville, North Carolina, on April 25, 1910. Jamesville was a village alongside the Roanoke River not far from the Outer Banks, where the Wright brothers first flew. The Browns scratched for a living on a small farm. The family’s prospects darkened when Archie was killed in an accident while Jimmy was a teenager.

Jimmy starred in high school ball as a shortstop and switch-pitcher. A natural right-hander, he had broken his right arm as a child and learned to throw lefty. He went to North Carolina State College (now North Carolina State University) to play baseball and basketball, but was in and out of school, possibly because of lack of money. He left for good in the last semester of his senior year to sign with the Cardinals in 1933. He was nearly 23 years old, but told the team he was 21.

The 5-foot-9, 139-pound shortstop was beaned in his second professional game at Class-B Greensboro. Manager Eddie Dyer told him he might as well quit, because he was sure to be afraid of the ball. Brown didn’t listen; he stayed and batted .289.

In only Brown’s second pro season, the club promoted him all the way to the top level of its farm system, Double-A Rochester. He stalled there because of his weak bat. Late in 1935, his second year with the Red Wings, he decided to become a switch-hitter. He took to it right away and batted .309 the next year.

During spring training in 1937, the Cardinals converted Brown to second base. The St. Louis infield was a jumble. Manager Frank Frisch was no longer able to play second every day, and his successor, Stu Martin, was slow to recover from an appendectomy. The club had sold third baseman Charlie Gelbert, who had never regained full strength after a shooting accident that nearly severed his left leg. Shortstop Leo Durocher was traded after the 1937 season.

Brown won the second-base job more because of his hustle and fire than his ability. That was why owner Breadon labeled the 160-pound pepper pot “a true-blue gas-houser,” a high compliment. While the club auditioned infielders for the next six years, Brown was the Jim of all trades.

| Games | 2B | 3B | SS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | 112 | 1 | 25 |

| 1938 | 49 | 24 | 30 |

| 1939 | 50 | 0 | 104 |

| 1940 | 48 | 41 | 28 |

| 1941 | 11 | 123 | 0 |

| 1942 | 82 | 66 | 12 |

Such versatility is rare. The most comparable player is Gil McDougald of the 1950s Yankees. More recently, Nick Punto divided his time almost equally between second, third, and short.

No matter where he played in the field, Brown hit .300 or close to it, but without power, and was one of the toughest batters to strike out. In his first year he usually batted second behind Terry Moore or Pepper Martin. After that he was installed in the leadoff spot.

Brown’s mother came to see him play for the first time on August 22, 1939, in Brooklyn. He was lining up to take a throw from the outfield when the Cardinals’ 210-pound first baseman, Johnny Mize, barreled into him and knocked him cold with an elbow to the temple. Brown was carried off the field on a stretcher as his mother and brothers Darroll and Elwood rushed to the clubhouse. He sustained a concussion, but was back in the lineup 11 days later.

Mize and Brown had been friends since their minor league days in Greensboro. Brown was best man in Mize’s wedding, and Mize returned the favor two days after the end of the 1939 season. He and his wife, Jene, stood up with Brown and his bride, Sarah Godley, a red-haired, blue-eyed nurse from Plymouth, North Carolina.

After Brown played primarily at shortstop in 1939, general manager Branch Rickey called him “our infield spark plug.”3 Then the GM listed three rookies who would try to take the job the next spring. One of them, Marty Marion, turned into a premier defensive shortstop, and Brown moved to third.

On his 30th birthday in 1940 (his 28th, as far as the Cardinals knew), Brown learned that the stories about the hot corner were all too true when a bad-hop grounder made a bloody mess of his nose. He tried to play through it, but could barely breathe and missed six weeks after surgery. While shuttling around the infield, Brown hit .280/.317/.335 in 107 games. He returned to St. Louis after the season for more extensive surgery to remove shattered bone fragments and rebuild his nose.

The Cardinals thought they had found their second baseman in 1941 in rookie Frank Crespi, who answered to the unfortunate nickname “Creepy.” Brown, back at third for most of the season, enjoyed the biggest day of his career on May 26. His bases-loaded triple capped the Cards’ seven-run third inning, but the Cubs came back to tie the game and went ahead 11-10 in the top of the 11th. Brown led off the bottom half with a home run to even the score again, and Don Padgett’s walk-off homer won it.

Despite missing nearly a month after he broke his right hand in a slide, Brown put together his career year in 1941: .306/.363/.406. He finished fourth in the Most Valuable Player vote. Brown’s injury was one of many that probably cost the Cardinals the pennant. They won 97 games, but their regular lineup took the field together only 23 times as they finished 2½ games behind Brooklyn.

St. Louis had been assembling a young team from the majors’ largest farm system. The final pieces were called up in September 1941: outfielder Stan Musial, third baseman Whitey Kurowski, and pitcher Johnny Beazley. In 1942 manager Billy Southworth’s starting lineup included only two players older than 27, Brown and Terry Moore, the center fielder and captain.

Brown opened the season at third base with Crespi at second. By late May the Cards had fallen 6½ games behind defending champion Brooklyn when Southworth shuffled the deck. He moved Brown to second and put the rookie Kurowski at third. Johnny Hopp, the fastest man on the team, took over at first (Mize had been traded to the Giants). Still, the club spent the summer chasing the Dodgers.

By early August they had dropped 10 games back. A leading New York bookmaker took the pennant race off the board; he had decided it was over. The Cardinals disagreed. They sprinted to the greatest finishing kick in baseball history, winning 44 of their last 53 games, and 106 in all, two more than the Dodgers.

The smart money said the outcome would have been different if the Brooklyn’s electric center fielder, Pete Reiser, hadn’t cracked his skull on the concrete wall in St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park in July. But the Dodgers played .714 ball after Reiser’s injury — a red-hot pace, just not hot enough. The Cardinals’ blazing two-month streak figured out to .829.

They did it with “dash and youth,” according to their manager.4 The team was called the “St. Louis Swifties.” With Mize gone, Enos Slaughter ’s 13 home runs led the club; Musial, with 10, was the only other Cardinal in double figures. Although they didn’t steal bases, they always took the extra base — first to third, second to home — and led the majors in doubles and triples. They scored the most runs in the National League while allowing the fewest. Musial, Marion, and other Cardinals later said it was the best team they ever played on.

That cut no ice with the smart money. The Yankees were overwhelming favorites in the World Series because, after all, they were the Yankees. The opening game followed the script. New York battered the Cardinals’ ace, Mort Cooper, and St. Louis committed four errors. The Yanks’ Red Ruffing pitched no-hit ball for 7 2/3 innings as the Bombers built a 7-0 lead.

The Cards woke up in the bottom of the ninth with a typical Swifties rally: four singles (one by Brown), a walk, and Marion’s triple brought home four runs with two out. The rookie Musial came to bat with the bases loaded, representing the winning run. He grounded out to end the game, but the young Cardinals had learned that the Yankees didn’t wear a big red “S” on their chests.

St. Louis won the next four, though the scores were relatively close. Kurowski sealed the championship with a ninth-inning homer in Game Five. Brown delivered six singles in 20 at-bats, plus three walks, for a .391 on-base percentage.

The Cardinals’ best season was Brown’s worst. Though he started his only All-Star Game in 1942, he was the weakest hitter in the league’s strongest lineup at .256/.315/.320. Teammates and sportswriters pointed to his “intangibles,” maybe because he was small or maybe because he was loud. A “holler guy” in the infield, his rapid-fire chatter rivaled a North Carolina tobacco auctioneer. His uniform was always dirty, his shirttail usually hanging out. Coach Mike Gonzalez said (as a sportswriter rendered his Cuban accent), “I satisfy if I have nine Jingy Browns. If I do I win plenty pennant and make many buckerinos.”5

Jimmy and Sarah were awaiting the birth of their first child. Their daughter, born on February 7, 1943, lived less than 24 hours. They later had a son, James Jr. A month after the family tragedy, Jimmy was called for his draft physical. He opened the season on borrowed time, and was inducted into the Army Air Force on June 29.

Assigned to the Air Transport Command, Brown spent his 2½ years in military service at the Memphis Army Air Field in Tennessee, where he was player-coach of the baseball and basketball teams. He did not play in 1945 because a fungus infection stripped the skin off his hands.

Brown joined hundreds of major leaguers coming home from the military for the 1946 season. The Cardinals, with their huge farm system, had a logjam at nearly every position. Brown was the oldest of four candidates for second base, along with Emil Verban, Lou Klein, and the 1945 rookie Red Schoendienst.

Owner Sam Breadon spent the winter disposing of some high-priced talent to clear the way for younger and cheaper players. He dealt away catcher Walker Cooper, first baseman Ray Sanders, and outfielder Johnny Hopp. In January Breadon sold Brown to Pittsburgh for a reported $30,000. Rejoining his first big-league manager, Frank Frisch, he began the season as the regular second baseman, but was soon demoted to a utility role and saw time at all three of his familiar infield spots.

As the war veterans returned, many were feeling a new spirit of, if not rebellion, at least unrest. Men who had fought for their country felt entitled to respect. Others had had enough of following orders in military service. The ground was shifting, and baseball owners were feeling the tremors.

While Mexican League recruiters were tempting players with large cash bonuses, a labor organizer from Boston, Robert Murphy, was peddling hope. Murphy’s American Baseball Guild promised to free the players from the owners’ tyranny. He targeted the Pirates as his first test because Pittsburgh was a strong union town and the club’s roster included many nondescript veterans who were barely hanging on in the majors.

Murphy claimed 90 percent of the Pirates had joined the Guild, along with a majority on six other teams. Two of the minority who refused to join were Brown and Rip Sewell, a 39-year-old pitcher. Both came from the South, where “union” was often a dirty word.

On June 5 Murphy met with club president William Benswanger, the grandfatherly son-in-law of the late owner Barney Dreyfuss, and asked him to recognize the Guild as the players’ bargaining representative. The answer was no. The Pirates’ lawyers said they didn’t want to disrupt the season; they would talk to Murphy in the fall.

Enraged by the delaying tactic, Murphy committed a rookie mistake. He called for a strike vote two days later without knowing whether he could win. The Pirates didn’t come out for batting practice as a Friday night crowd of nearly 17,000 filed into Forbes Field. Frisch ordered Murphy out of the clubhouse, and the manager went into his office, leaving the players to hash it out.

The team was so bitterly divided that captain Al Lopez advised the rookie Ralph Kiner to stay out of the debate for his own good.6 Even some players who felt abused by management were hesitant. Most of them had been scraping by on army pay for two or three years and couldn’t afford to be suspended. Murphy, red-faced and ranting, hadn’t helped his cause; his belligerence alienated some of the Pirates.7

Sewell, Brown, and outfielder Bob Elliott — the highest paid Pirates — argued the case against a walkout. Sewell urged his teammates not to listen to Murphy, an outsider who knew little about baseball. He and Brown said they would play that night, strike or no strike. Frisch was cobbling together a replacement lineup including himself and 72-year-old coach Honus Wagner.

After two hours, Pirates executive Bob Rice stuck his head out of the clubhouse door and told the impatient writers, “No strike.” In a secret ballot, a majority of the team had voted to walk out, but the players had agreed in advance that they wouldn’t strike unless two-thirds approved. The tally was reported to be 20-16, four votes short.8

Sewell led the club onto the field. When Brown came to bat, leading off the bottom of the first, he heard some boos. Pittsburgh was a union town. He went 3-for-5 with two RBIs as the Pirates walloped the Giants, 10-5.

That was the end of the Guild, but it was not the end of the players’ grievances. The Guild threat, coupled with the Mexican League invasion, convinced the owners that they had better deal with their employees’ complaints. They agreed to meet with player representatives for the first time since John Montgomery Ward’s Players Brotherhood in the 1880s.

The talks produced some concessions, including a $5,000 minimum salary, $25 weekly expense allowance during spring training (players called it Murphy money), and a pension plan. Columnist Red Smith scoffed that the owners were “tossing the help a bone.”9 Nobody challenged the reserve clause that bound players to their teams for life. But it was the first crack in the owners’ iron rule. Twenty years later, concern about the pension plan led the players to hire Marvin Miller as executive director of their association.

A postscript: Several weeks after the strike vote, four men jumped Brown in a parking lot outside Forbes Field and beat him up. He came away with a black eye, other bruises, and a skinned elbow. He said the men wanted to rob him, but they ran off without stealing anything.10 There was no evidence connecting the attack to his anti-union activity, but Sewell later said Murphy had threatened him with a beating.11

Brown was finished as a player. His speed was gone, and he batted only .241 in 79 games. He was 36, not 34 as the record books said. That was old for an infielder, even without considering the impact of his long layoff from professional competition.

When Pittsburgh released him at the end of the season, the club rewarded his loyalty with its top minor league managing job at Triple-A Indianapolis in 1947. He moved to Double-A New Orleans the next season, then joined the Boston Braves for three years as first-base coach under his former Cardinals manager Billy Southworth. Brown was let go after Southworth resigned during the 1951 season.

For the next 13 years Brown was a minor league nomad, managing 10 teams in the St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Milwaukee organizations with winter jobs in Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and Colombia. He rose as high as the Double-A Texas League, but spent most of those years in the low minors.

In July 1964 he resigned as manager of Greenville in the Western Carolina League and left baseball for good. He lived out his life on his farm in Bath, North Carolina, and died at 67 on December 29, 1977.

“I’ve played with and against some wonderful people,” Brown wrote in a questionnaire for the Hall of Fame. “Their frindship [sic] and the people I’ve met, plus all the good people in baseball that make it possible for so many boys to play our wonderful game, make it the best sport in every way.”12

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 “Legal Bulwarks for Game Backed by Sen. Johnson,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), August 15, 1951: 8. The third man Chandler referred to was John “Frenchy” DeMoisey, an assistant to the commissioner who advised Pirates management on dealing with the union.

2 Dick Farrington, “Breadon Optimistic, But Won’t Say Flag,” TSN, January 14, 1937: 3.

3 “Sid Keener’s Column,” St. Louis Star-Times, December 6, 1939: 28.

4 Charles Dunkley, “Kurowski Loses His Pants During Victory Celebration,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 6, 1942: 10.

5 Roy Stockton, “Little Mr. Jimmy Will Give Bucs All He Has,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 8, 1946: 12.

6 Frederick Turner, When the Boys Came Back (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1996), 139.

7Chester L. Smith, “Pirate Players Threaten Strike,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 6, 1946: 1.

8 Vince Johnson, “Pirates Vote to Call Off Strike,” Post-Gazette, June 8, 1946: 1; Smith, “Pirates Reject Strike Planned By Guild, Take Field, Defeat Giants,” Post-Gazette, June 8, 1946: 1. Rosters were expanded to make room for returning servicemen, explaining the 36 votes.

9 Red Smith, syndicated column, July 31, 1946, reprinted in Red Smith on Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2000), 10.

10 “Brown Beats Off 4 Men Seeking Baseball Gear,” Post-Gazette, July 21, 1946: 22.

11 William Marshall, Baseball’s Pivotal Era, 1946-1951 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999), 70.

12 Questionnaire in Brown’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

James Robertson Brown

Born

April 25, 1910 at Jamesville, NC (USA)

Died

December 29, 1977 at Bath, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.