Jimmy Zinn

And out again I curve and flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on for ever.

— from The Brook by Alfred Lord Tennyson

“Jimmy Zinn … is like Tennyson’s brook — goes on forever.” — sportswriter Moulton Cobb1

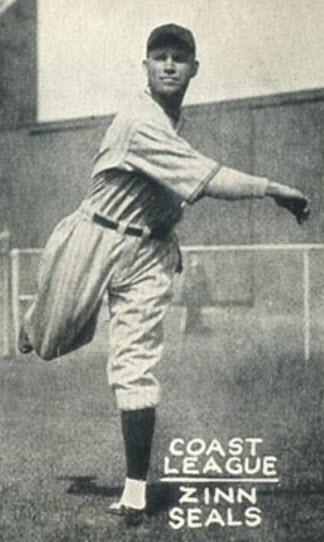

Though Jimmy Zinn won only 13 games in the majors, he was an ace of top minor-league teams, including the Kansas City Blues and San Francisco Seals. The durable right-hander compiled a 308-214 record in a career that spanned a quarter-century from 1915 to 1939. He pitched to Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, and played alongside Joe DiMaggio. Zinn was an excellent hitting pitcher, with a .303 career batting average.2

Though Jimmy Zinn won only 13 games in the majors, he was an ace of top minor-league teams, including the Kansas City Blues and San Francisco Seals. The durable right-hander compiled a 308-214 record in a career that spanned a quarter-century from 1915 to 1939. He pitched to Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, and played alongside Joe DiMaggio. Zinn was an excellent hitting pitcher, with a .303 career batting average.2

James Edward Zinn was born on January 31, 1895, in Benton, Arkansas, about 25 miles southwest of Little Rock. He was the eldest of four sons born to John and Virginia Zinn. John worked on train cars as a carpenter and inspector.3 In May of 1914, James graduated from Argenta High School in North Little Rock, where he starred on the baseball, football, and basketball teams.4

The big youngster — about 6-feet-1 and 195 pounds — was invited to spring training in 1915 with the Waco Navigators of the Class B Texas League, and the Navigators farmed him out to the Fort Smith (Arkansas) Twins of the Class D Western Association. In his first start for the Twins, on April 13, 1915, Zinn delivered a six-hit shutout of the Muskogee (Oklahoma) Mets, and on May 27, he went the distance against the Mets in a 19-inning 1-1 tie.5

Zinn had a 12-3 record for the Twins and a 1.61 ERA when he was in a serious accident on July 3, 1915. He was thrown from an automobile, and landed on and injured his right shoulder, his future as a pitcher in doubt. He recovered enough to pitch for the Navigators the following spring, but shoulder pain prematurely ended his 1916 season. The Philadelphia Phillies nonetheless saw Zinn’s potential and invited him to spring training in 1917.

While nursing his sore shoulder at the Phillies’ training camp, Zinn was tutored by the great Phillies ace, Grover Cleveland Alexander, who got him to switch from a painful overhand delivery to a comfortable side-arm motion. Zinn learned from Alexander how to throw an effective side-arm sinkerball, as well as a slider and curve. These lessons were the key to Zinn’s future success.

The Phillies returned Zinn to Waco, and on April 19, 1917, he threw a no-hitter at Fort Worth using the side-arm delivery he learned from Alexander. That season he posted a 14-8 record for the Navigators with a 2.30 ERA.

Zinn enlisted in the Army in August of 1917, during World War I, and while stationed at Camp Bowie, near Fort Worth, in 1918, he pitched in a few games for Waco while on furlough. Later, in France, he drove an ambulance between the front lines and the medical headquarters. After his release from the Army in June of 1919, he returned once again to pitch for Waco.

On August 11, 1919, the Navigators sold Zinn’s contract to the Philadelphia Athletics. He made his major-league debut on September 4, in the first game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia, against Walter Johnson and the Washington Senators. The Senators clouted Zinn’s pitches for eight runs on 14 hits, including a long home run by Johnson.

Five days later, Zinn earned his first major-league victory by beating the Detroit Tigers, 4-3, in Philadelphia. Ty Cobb went 3-for-5 and drove in all three Detroit runs. Zinn, a left-handed batter, helped his own cause by hitting two singles.

Zinn’s competence with the bat inspired Athletics manager Connie Mack to use him as a pinch-hitter. In Philadelphia on September 15, Zinn slugged a ninth-inning, pinch-hit three-run homer off Red Faber of the Chicago White Sox.

Zinn balked at signing a contract for the 1920 season, saying Mack’s offer was no better than what he earned in Waco, so Mack sent him back to Waco. The Navigators had relocated and were now the Wichita Falls (Texas) Spudders, affiliated with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

For the 1920 Spudders, Zinn went 18-10 with a 2.20 ERA and batted .342 in 158 at-bats. On May 23, he played left field and contributed a single, double, and home run in a 9-2 victory at Fort Worth. And on July 29, he went 5-for-5 at the plate and pitched the first game of a doubleheader in Beaumont, Texas, a 9-4 triumph for the Spudders.6

But those feats do not compare to Zinn’s performance on August 22, in a doubleheader at Wichita Falls against the Houston Buffaloes. He threw a no-hitter in the first game and crushed a two-run homer in the sixth inning “over the right field fence for the longest drive ever made on the local grounds.”7 And in the second game, he tossed a three-hit shutout in a seven-inning contest. In total, he pitched 16 scoreless innings that day, allowing three hits and two walks.

Upon the recommendation of scout Don Curtis,8 the Pirates acquired Zinn and he joined the club in early September. Manager George Gibson let Zinn pitch for the team in an exhibition game against Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees on September 8. Zinn was thrilled with the opportunity and anxious to show what he could do.

Ruth was a sensation. In a doubleheader at Boston on September 4, he slugged his 45th and 46th home runs of the season, setting the record for most home runs in one season in professional baseball history. On September 8, an overflow crowd of 26,000 fans packed Forbes Field in Pittsburgh to see Ruth play, hoping to see him hit a home run.

Facing Zinn, Ruth drew a walk in the first inning, flied out to left field in the third inning, and lined a single to center field in the sixth. And in the seventh inning, Zinn struck him out. Gibson was furious. “What the hell are you doing?” he said to Zinn. “Everybody is here to see Ruth hit a home run!” Zinn took offense at getting scolded for pitching well and exchanged harsh words with his manager.

In the ninth inning, Pirates third baseman Possum Whitted let Ruth’s foul popup hit the ground so that Ruth would have one more chance to hit a home run. Zinn obliged by grooving a pitch that Ruth belted far over the right-field wall. As reported by Edward F. Balinger of the Pittsburgh Daily Post: “Ruth’s homer was followed by a wave of cheering that was deafening. Straw hats were shied upon the playing field and the crowd fairly went wild with delight. The applause did not subside for fully five minutes.”9 The final score was Yankees 7, Pirates 3, but the score was immaterial — the fans went home happy.

On September 25, Zinn earned his first victory for the Pirates in the first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Cardinals in Pittsburgh; he pitched all 12 innings of a 2-1 thriller. A week later in Pittsburgh, he played against the Cincinnati Reds in the last tripleheader in major-league history (through 2016). He sat out the first game, which was won by the Reds; pitched and lost the second game; and played right field in the third game, a six-inning contest won by the Pirates.

Zinn came to the Pirates’ spring-training camp in 1921 with his brother, Johnny, a catcher, but Johnny did not make the team.10 The 1921 Pirates were a strong team and finished the season in second place, four games behind the New York Giants. Zinn was a spot starter who worked mostly in relief. He threw his first major-league shutout on May 30, 1921, a five-hitter against the Chicago Cubs in the first game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh. Against the Phillies on August 5 at Pittsburgh, he pitched six innings in relief and earned the victory; it was the first game in major-league history to be heard on radio, with play-by-play broadcast live by Pittsburgh’s KDKA.11

The Pirates used Zinn sparingly in the spring of 1922, and he demanded his release so that he could go somewhere he could pitch regularly.12 The team complied by sending him to the Kansas City Blues of the Double-A American Association, with whom he achieved an 18-5 record in 217 innings. After the season, on October 16, 1922, he pitched for the Blues in an exhibition game against the Kansas City Monarchs, a premier Negro League team. The Monarchs won 2-1, and Zinn acknowledged, “They beat me at my best.”13 About this time, the 27-year-old pitcher married 24-year-old Grace Brown, and their son, James Jr., was born on August 31, 1924.

In the estimation of historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, the 1923 Kansas City Blues rank as the 18th best minor-league team of all time.14 The team won the American Association pennant with a 112-54 record and then defeated the Baltimore Orioles in the Junior World Series. Zinn was the Blues’ leading pitcher with a 27-6 record, and he hurled a one-hitter to defeat the Orioles in the third game of the Series. The Orioles were impressed with Zinn’s great control and baffling speed and curves, said Don Riley of the Baltimore Sun.15

Over the next three seasons, Zinn had a combined record of 46-45 for much weaker Kansas City teams. His batting average during this period was a robust .336. On July 20, 1926, in the first game of a doubleheader at Columbus, Ohio, he went 6-for-6 at the plate, with four singles, a double, and a triple.16

Zinn’s record for the 1927 Blues was 24-12, and his 3.08 ERA led the league.17 And he earned a return trip to the major leagues after posting a 23-13 mark for the 1928 Blues. Though he turned 34 years old in January of 1929, the Cleveland Indians acquired him, willing to give him another try at the major-league level.

Zinn lost his first start for the Indians, 5-0, to the St. Louis Browns in Cleveland on May 24, 1929, but he shined in his next two starts, an 11-1 thrashing of the White Sox in Chicago on May 29, and a 4-0 blanking of the Red Sox in Boston on June 4. In those two victories, he was helped by Indians first baseman Lew Fonseca, who exploded for seven hits in 11 at-bats, with one single, one double, two triples, three home runs, and six RBIs.

However, after that, Zinn was used sporadically and was mostly ineffective, with a 6.09 ERA in 15 appearances. The Indians declared him “a bust” and sold him in December to the San Francisco Seals of the Double-A Pacific Coast League.

But Zinn was not washed up. His record for the 1930 Seals was 26-12, and on May 14, 1930, he threw a no-hitter against the Sacramento Senators in Sacramento.18 Indians general manager Billy Evans went to the West Coast to scout for pitchers and said the best one he saw was Zinn, the man he had let go in December.19

Zinn missed two months of the 1931 season after injuring his arm while sliding back to first base, but he returned in good form and won the third game of the Seals’ postseason playoff series against the Hollywood Stars.20 The Seals swept the series, four games to none, to win the PCL championship.

One of Zinn’s teammates on the Seals was teenager Joe DiMaggio. In San Francisco on July 26, 1933, Oakland Oaks pitcher Ed Walsh Jr. held DiMaggio hitless to end his 61-game hitting streak, but the Seals prevailed, 4-3, as Zinn tossed a six-hitter.21

The Seals released the 40-year-old Zinn in May of 1935, and he finished the season with the Sacramento Senators. He pitched for semipro teams in California in 1936, and served as player-manager of the El Paso Texans of the Class D Arizona-Texas League in 1937 and 1938. He later managed teams in Jacksonville (Texas), Sioux City (Iowa), Albuquerque, Fort Lauderdale, and Gadsden (Alabama) between 1939 and 1948. During World War II, he worked at the Maumelle Ordnance Works in Arkansas.

Zinn’s son, James Jr., grew up to be a smooth-fielding second baseman and played in the minor leagues from 1946 to 1953.

Zinn worked for the Arkansas State Highway Department from 1949 until his retirement in 1962.22 In his retirement, he and his wife worked with disabled children at the Conway (Arkansas) Children’s Colony.

Like Tennyson’s brook, Zinn kept on going, until February 26, 1991, when he died at age 96 in Memphis, Tennessee. His wife died a year later. They were buried at the Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Interview of Jimmy Zinn by Mark Bernstein on October 7, 1989, SABR Oral History Project.

Zinn’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 Bryan (Texas) Eagle, May 23, 1927.

2 Computed by combining major- and minor-league batting statistics retrieved from Baseball-reference.com in July of 2017.

3 1910 and 1920 US Censuses.

4 Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), December 6, 1913, and May 29, 1914.

5 Daily Arkansas Gazette, April 14 and May 28, 1915.

6 Shreveport (Louisiana) Times, May 24 and July 30, 1920.

7 Shreveport Times, August 23, 1920.

8 Waco (Texas) News-Tribune, May 2, 1921.

9 Pittsburgh Daily Post, September 9, 1920.

10 Pittsburgh Daily Post, March 30, 1921.

11 Muncie (Indiana) Star Press, April 8, 1979.

12 Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), December 30, 1922.

13 Kansas City Kansan, October 17, 1922.

15 Baltimore Sun, October 15, 1923.

16 Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 21, 1926.

17 Minneapolis Star Tribune, November 16, 1927.

18 Los Angeles Times, May 15, 1930.

19 Louisville Courier-Journal, July 26, 1930.

20 San Mateo (California) Times, October 9, 1931.

21 Oakland Tribune, July 27, 1933.

22 Memphis Commercial Appeal, February 28, 1991.

Full Name

James Edward Zinn

Born

January 31, 1895 at Benton, AR (USA)

Died

February 26, 1991 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.