Joe Buzas

“If after five years in the Yankee chain, I still am not eligible for major league baseball, what’s the use of kidding myself? If I can’t make the big leagues in this war situation, I should go into something that has a better future.”1 Those were the words of Joe Buzas when directed during the 1945 season to report to manager Casey Stengel in Kansas City, the New York Yankees farm team in the American Association.2

“If after five years in the Yankee chain, I still am not eligible for major league baseball, what’s the use of kidding myself? If I can’t make the big leagues in this war situation, I should go into something that has a better future.”1 Those were the words of Joe Buzas when directed during the 1945 season to report to manager Casey Stengel in Kansas City, the New York Yankees farm team in the American Association.2

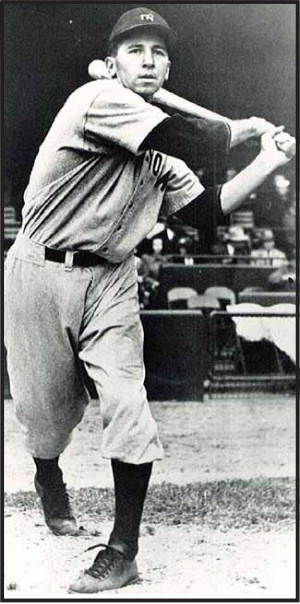

Joseph John Buzas was born on October 2, 1919, in Alpha, New Jersey, a small town near the Pennsylvania coal country. His immigrant parents, John Joseph and Anna, were born in Budapest, Hungary, and owned a grocery store where Joe worked through his school and minor-league years. He was a three-sport star at Phillipsburg (New Jersey) High School, where he was the baseball team’s captain and leading hitter.3 At Bucknell University he majored in business and played football, basketball, and baseball, and was on the boxing team. Before attending Bucknell on a baseball scholarship, Buzas turned down an offer by the Philadelphia Athletics to pay for his education at Duke University.4 A line-drive hitter able to hit to all fields, Buzas was Bucknell’s leading hitter for three years and his .378 career average stood as one of the best in the school’s history.5 He also pitched. In one game against Temple University he struck out 16 batters.

While at Bucknell, Buzas was invited by the Detroit Tigers to attend a workout in Detroit with other college players. He was selected as the outstanding player at the camp, but since he had grown up a Yankees fan and it was his lifelong dream to wear the Yankee pinstripes, he turned down an offer from the Tigers.6

Buzas first attracted the attention of the Yankees while playing with a Tremont, Pennsylvania, semipro team against the Brooklyn Bushwicks. Yankees scout Paul Krichell signed him out of college in 1941 for a $7,500 bonus.7 (He completed his degree in 1942.)8 Third base was his regular position, but the Yankees intended to groom him as a middle infielder.9 Krichell believed that Buzas had great potential, a natural player who would make the grade.

Buzas played for Yankees farm teams at Akron, Norfolk, Trenton, Binghamton, and Newark before reaching the major leagues. He also played winter ball in California to stay in shape and worked as a safety inspector at the Navy dry dock on Terminal Island, near Los Angeles.

Playing for Norfolk in 1941, Buzas made the Piedmont League all-star team as a third baseman. When Hall of Famer Pie Traynor was scouting for the Pirates he saw Buzas play at third in 1941 and said that Joe was the best third baseman he had ever seen in the minors.10

Playing football at Bucknell almost brought an early end to Jersey Joe’s career in baseball. It was fall 1940 that Joe hurt his arm making a tackle. The weakened arm kept Buzas down in the minors. He started with Akron in the Middle Atlantic League and from there to Norfolk in the Piedmont League. In 1942 he was with Trenton of the Inter-State League and finished up with Binghamton in the Eastern League. When his arm improved he moved up to the Newark Bears of the Double-A International League. Buzas led the 1943 Newark team in stolen bases with 24, and played second, third, and shortstop.

In 1944 at Newark, Buzas batted .297 and again led the team with 29 stolen bases. He was second on the team in RBIs with 65 and played mainly at second base with some stints at third. In the league playoffs he tied an International League record with four steals in a game against Baltimore. He then broke the record for steals in a series with a fifth steal in the final game of the playoffs as Newark lost to Baltimore.11

In 1944 Buzas had been invited to the Yankees’ spring-training camp in Atlantic City, New Jersey. New York’s Joe Gordon was about to go off to fight the war, but Buzas was 4-F because of a perforated eardrum. His throwing shoulder bothered him because it had been hurt in a baseline collision. One day manager Joe McCarthy called Buzas over to tell him, “Joe, I’m sending you home. It hurts me to see you throw.”12 Eventually he returned to Newark and played in 125 games, batting .297. That brought him another invitation to big-league spring training in 1945. Veteran Frankie Crosetti was a holdout and owner and the Yankees were ready to write Crosetti off and give Buzas the promotion. Buzas was the starting shortstop on Opening Day, batting sixth in the lineup. He had one hit, an RBI, and a run scored. “I’ll never forget the thrill of opening day. My feet never touched the ground when I went out to take my position at shortstop,” he told a sportswriter in 1981.13

Buzas played the first 12 games of the season at shortstop for the Yankees. He was hitting .286 (14-for-49) with an on-base percentage of .314, had knocked in six runs and stolen twice in two attempts. The Yankees were in first place by a half-game with a record of eight wins and four losses. Then Crosetti ended his holdout, and Buzas had played his final game at shortstop. Over the next 47 games he appeared strictly as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. As a pinch-hitter he was 3-for-16. His played his final game in a Yankees uniform on June 28 as a pinch-runner.

It was after the June 28 game that manager McCarthy called Buzas in to tell him that he wanted him to go to Kansas City to improve as a shortstop by playing every day.14 Buzas described himself as a “hard-headed Hungarian”15 and he told Yankees general manager George Weiss that he would not go to Kansas City even for a promise on the future. Weiss replied that he would confer with team president Larry MacPhail. While this waiting game was going on it was rumored that the Phillies were interested in Buzas. The Yankees sought outfielder-first baseman Jimmy Wasdell in exchange. Buzas declared, “I will not play any more ball in the minor leagues, and that is definite. … I would not accept a transfer back to the [Newark] Bears any more than I am taking a shift to Stengel [in Kansas City]. It’s the big leagues or nothing.” Buzas added, “I tried hard for McCarthy. I hustled my head off even when I was sitting on the bench. I think Joe (McCarthy) liked me. Sure, I couldn’t play with Crosetti. But how many can?”16

Sportswriter Dan Daniel thought Buzas could run and he could hit left-handers, if nothing else. His role as a pinch- hitter and pinch-runner could have been of help to the Yanks. But Kansas City was badly in need of players. Furthermore, as far as Daniel could discern, “Buzas could not displace any shortstop now playing regularly in the American League. The position is fairly new to him and he needs plenty of experience in it.”17

Garry Schumacher of the New York Journal-American wrote, that “Buzas has the makeup of a great shortstop. Critics believe he may be a sensation.”18 Schumacher added, “There is an effortless grace about him, a rhythm that reflects his fine physical co-ordination. Body control, is what Branch Rickey called it, and Buzas defined exactly what that meant. His big hands are strong and sure. Joe always seems to be in front of ground ball chances, bent low to meet them, hands ready to clamp down on the ball. With every grounder he comes up with a handful of dirt, like the twin claws of a scoop shovel. Though there is some doubt about the strength or power of his arm, timing and accuracy will be the substitutes, particularly in double plays.”19

Buzas eventually gave in and agreed to return to Newark (.255 in 61 games). In 1946 he started the season with Newark (.233 in 62 games) and finished up in the Pacific Coast League with the Seattle Rainiers, batting .291 in 55 games. While at Newark, Buzas was the victim of a near-fatal pitch thrown by Harry Jordan of Toronto. This was the second time in his career that he suffered a severe beaning. (The first occurred in 1942 and caused dizzy spells.) The pitch by Jordan hit him behind the ear. Joe was sent to the hospital and had his spine tapped. The examining doctor said, “This guy is lucky if he lives to be 50.”20 Years later (in 1983) Buzas went deaf in this ear. The statement, not the medical diagnosis, had a major impact on how Joe was to conduct his life.

The bad shoulder and the beaning were too difficult to overcome. According to his daughter Hilary Drammis, Buzas began suffering from severe migraines that gave him difficulty playing under the lights.21 His hopes of returning to the majors were now shattered. But Buzas was not ready to quit. For the 1948 and 1949 seasons he was player-manager of the Sunbury (Pennsylvania) Reds of the Class B Inter-State League. During the winters he played and managed in Puerto Rico for 12 years (1945-1951, 1953-1955, and 1963-1964) with the Mayaguez, Aguadilla, San Juan, and Ponce teams. The fans loved his aggressive and argumentative style of play and managing, so much so that they chipped in to buy him a new Oldsmobile in 1948. Buzas remarked, “The fans called me a real Puerto Rican. I had a temper like them. I used to argue with the umpires and get kicked out of a lot of games.”22 After his Puerto Rico days were over, he left baseball for a short while. He returned to his hometown of Alpha and went into the construction business with his brother and also ran a discount department store.

Buzas had married Helen Penelope McConnell, a teacher at St. Mary’s School in Alpha, in 1944. They raised two children, Jason, who became a theater director in New York City, and daughter Hilary Drammis, a clinical psychologist.

Buzas began his career as what some called a “baseball chain-store operator” in 1957 when he was asked by Eastern League President Tommy Richardson to take over a team in Syracuse that was moving to Allentown, Pennsylvania. The cost to Buzas would be zero!23 He went on to own a reported 82 minor-league franchises over 47 years.24 The family, particularly Hilary, was very much involved in their father’s baseball operations. After Allentown, next came teams in the New York-Penn League, the Carolina League, and the Western Carolinas League. At the 1972-1973 winter meetings in Hawaii, Buzas acquired the Louisville franchise and moved it to Pawtucket in the International League. He said, “Owning a Triple-A team is the top thrill I have had in all my years in baseball.”25

The move forced Buzas to search for a new site for Pawtucket’s Eastern League franchise. He was turned down by Meriden, Connecticut, but was able to reach an agreement with Bristol, Connecticut.26 Buzas now owned three farm clubs of the Boston Red Sox – Winston Salem in the Class-A Carolina League, Double-A Bristol, and Triple-A Pawtucket. In 1967 when he acquired the Knoxville team in the Southern League he became the first minor-league owner in baseball history to have simultaneous affiliations with three different teams.27 Knoxville was a Reds farm team, the Eastern League Pittsfield franchise was a Red Sox affiliate, and the Oneonta team in the New York-Penn League became a Yankees affiliate in 1967.

Here is a partial list of Buzas’s ownership interests: Red Sox Eastern League franchises in Allentown from 1957-1960, Johnstown 1961, York 1962, Reading 1963-1964, and Pittsfield 1965-1969; the Oneonta Red Sox (New York-Penn League) in 1966 and the Oneonta Yankees (New York-Penn League) in 1967; the Knoxville Reds (Southern League) in 1967; the Savannah Senators (Southern League) in 1968-69); the Pawtucket Red Sox (Eastern League) 1970-1972; the Pawtucket Red Sox (International League) 1973-1974; the Winston-Salem Red Sox (Carolina League) 1970-1974; the Sumter Indians (Western Carolinas League) 1970; the Bristol Red Sox (Eastern League) 1973-1982; the New Britain Red Sox (Eastern League) 1983-1994; the Hardware City Rock Cats (New Britain, Eastern League), 1995-1996; the Elmira Pioneers (New York-Penn League) 1977-1978; and the Reading Phillies (Eastern League) 1977- 1985.

In 1977 Buzas placed the New Britain team in his daughter Hilary’s name. It was the only way he could own two teams in the Eastern League at the same time. In 1986 Buzas purchased the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League, a Phillies Triple-A franchise. In 1992 and 1993 the Beavers became a Twins affiliate. He then moved the team to Salt Lake City. The Salt Lake Buzz, a Twins franchise, changed its name to the Stingers in 2001 because of a trademark dilution lawsuit brought by Georgia Tech. In 2001 the Stingers became an Angels franchise. In 1996 Buzas received the John J. Johnson President’s Trophy, minor-league baseball’s top award, as “Owner of the Year.” In New Britain a plaque outside New Britain Stadium honors Buzas.28

The key to success as a minor-league club owner, Buzas said, is “common sense, strong promotions, improvising as you go along, getting to know the fans and, above all, hard work. But if you don’t love baseball, you’re not going to make it as a club owner in the minor leagues.”29

As a baseball executive, Buzas was extremely cost-conscious. He was known to personally clean baseballs to save a buck.30 “When I die, I want my epitaph to read: ‘Here lies Joe Buzas. He cleaned more than one million baseballs while owning more baseball clubs than anyone else in the game’s history,’” he said.31

In order to cut costs in operating his ballclubs, Buzas would enlist the members of his family to work the concession stands and turnstiles. Joe himself could be seen serving hot dogs or taking tickets. He became a supersalesman, selling fence and program advertising. When his teams were not playing at home and during the offseason, Buzas would put on promotional and other events – boxing or wrestling matches, for example – to make use of the ballparks. While driving from team to team he would use a tape recorder for the ideas that popped into his head. He always drove a Cadillac, trading in for a new one every two years.

Buzas wrote a 12-page pamphlet on how to run a minor-league baseball team. He could at times be gruff and overbearing, but he was compassionate and understanding. He would never allow someone to suffer needlessly, his daughter said. All one had to do was ask and Joe would give money, if necessary, or somehow make sure that the person’s basic needs were met. He never turned his back on anyone.32 He would treat everyone as an equal. He was a volunteer fireman and loved to hang out at the fire station playing pinochle. According to daughter Hilary, he would come home thrilled if he had won 50 bucks.

Joe Buzas’s major-league profile card read reads 3B, throws right, bats right, 6-feet-1/2 inch, 180 pounds, and lists football as his second favorite sport. In 1995 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and won the battle. At that time he continued to operate his baseball business with daughter Hilary, who became a co-owner of the Salt Lake team, until he came down with a long illness that resulted in extreme weight loss. He died on March 19, 2003, in Salt Lake City and was cremated. Hilary Drammis continued to own and operate the Stingers until she sold the team in January 2005.

Sources:

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author relied on the Joe Buzas player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 Dan Daniel, “It’s Big Leagues or Nothing, Says Joe (no-Budge) Buzas,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1945.

2 Ibid.

3 Terese Karmel, “He’s No Bush Leaguer,” Hartford Courant, September 4, 1983.

4 Many Athletics had come from Duke, and former A’s pitcher Jack Coombs was the Duke baseball coach. Connie Mack Jr. had also played Duke Blue Devils baseball. http://www.heraldsun.com/durhamherald/x27232291/Duke-Blue-Devil-s-one-of-a-kind-baseball-matchup-in-1939

5 Karmel.

6 Doyle Dietz, Reading Eagle, February 1981. Otherwise undated clipping from Joe Buzas Hall of Fame player file.

7 Jack Cavanaugh, “Minor Leagues ’86: Joe Buzas a Baseball Man Who Is in a League All by Himself,” New York Times, August 10, 1986.

8 Rud Rennie, “Yankees Test Buzas as Second Baseman,” New York Herald-Tribune, undated 1944 clipping found in Buzas’s Hall of Fame player file.

9 1973 Pawtucket Baseball Club newsletter –“Meet Joe Buzas.”

10 Hall of Fame player file clipping dated August 19, 1986.

11 Dietz.

12 Hall of Fame player file clipping dated August 19, 1986.

13 Dietz.

14 Daniel.

15 Dietz.

16 Daniel.

17 Daniel.

18 Garry Schumacher, New York Journal-American, undated 1945 clipping found in the Joe Buzas player file at the Hall of Fame.

19 Ibid.

20 Hall of Fame player file clipping dated August 19, 1986, and as retold by daughter Hilary Drammis in telephone interview on July 21, 2014.

21 Hilary Drammis interview.on July 21, 2014

22 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League: A History of Major League Baseball’s Launching Pad (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995).

23 Cavanaugh.

24 Cavanaugh.

25 1973 Pawtucket newsletter – “Meet Joe Buzas.”

26 Bill Troberman, “Buzas Becomes Top Minor League Farmer,” The Sporting News, February 10, 1973.

27 Roger O’Gara, “Buzas Expands Minor-Loop Domain,” Berkshire Eagle, December 21, 1967.

28 Hartford Courant obituary, March 20, 2003.

29 Cavanaugh.

30 Karmel.

31 Cavanaugh.

32 Drammis interview; Karmel.

Full Name

Joseph John Buzas

Born

October 2, 1919 at Alpha, NJ (USA)

Died

March 19, 2003 at Salt Lake City, UT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.