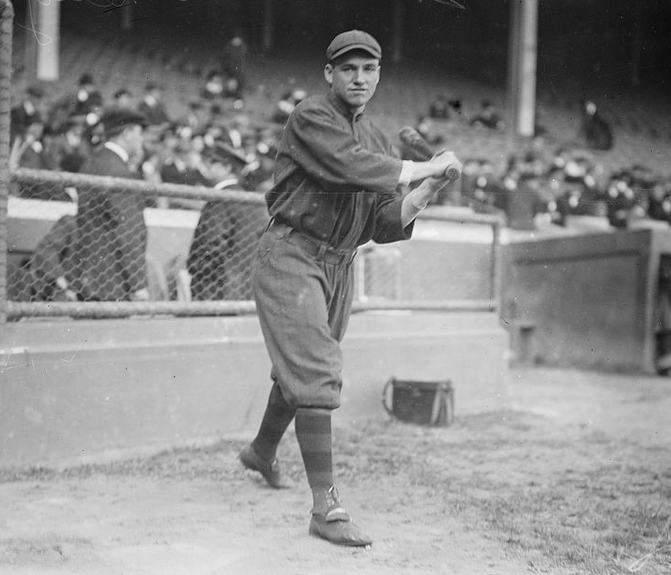

Joe Connolly

When baseball fans think about the national pastime and Rhode Island during the Deadball Era, Napoleon Lajoie stands out as the premier sports personality from “Little Rhody.” However, Joseph Connolly, despite just a four-year major-league career (1913-1916), may have had a greater impact on the social, cultural, and baseball fabric of Rhode Island than any other player, including Lajoie. As for Connolly’s athletic abilities, Paul Shannon of the Boston Sunday Post wrote that the Rhode Islander “is fairly fast, the possessor of a strong wing and he covers a good extent of territory. Furthermore, he is a dependable hitter.”1 Connolly was the offensive star of the Boston Braves during their most successful period of the Deadball Era (.288 lifetime batting average).

When baseball fans think about the national pastime and Rhode Island during the Deadball Era, Napoleon Lajoie stands out as the premier sports personality from “Little Rhody.” However, Joseph Connolly, despite just a four-year major-league career (1913-1916), may have had a greater impact on the social, cultural, and baseball fabric of Rhode Island than any other player, including Lajoie. As for Connolly’s athletic abilities, Paul Shannon of the Boston Sunday Post wrote that the Rhode Islander “is fairly fast, the possessor of a strong wing and he covers a good extent of territory. Furthermore, he is a dependable hitter.”1 Connolly was the offensive star of the Boston Braves during their most successful period of the Deadball Era (.288 lifetime batting average).

The Blackstone Valley River Canal Corridor extends 45 miles from Worcester, Massachusetts to Providence, Rhode Island. At the turn of the 20th Century, textile mills were located in both urban and rural sites along the Blackstone River. This geographical area was also a hotbed of baseball activity in the amateur, semiprofessional, and professional levels. It was within this context that Connolly lived.

Joseph Francis Connolly was the ninth of 11 children of Thomas Francis and Ellen (Powers) Connolly, emigrants from Ireland who married in Cumberland, Rhode Island during the last year of the Civil War, 1865, and established a family farm in the Sayles Hill section of nearby North Smithfield. Until recently, most baseball chronicles listed Joseph’s birthdate as either February 12, 1886 or February 12, 1888. But according to the birth records in the North Smithfield Town Hall, Connolly was born on February 1, 1884, a finding that is corroborated by documents in the Rhode Island State Archives as well as the baptismal record at St. James Church in the village of Manville, where the family worshiped because of its proximity to their home. During this historical period, it was the Roman Catholic tradition to have an infant baptized soon after birth. Even though the church register lists his date of birth as February 2, 1884, Joseph was definitely baptized on February 10, 1884. Despite a one-day discrepancy with respect to the day of his birth, legal documentation is in complete agreement regarding the birth year.

Connolly’s sons said that their father never liked to talk about his age.2 The reason for changing his date of birth may have been to protect and advance his baseball career, which was a common practice at the time. Even the family never knew that 1884 was the year he was born, for to them it had always been February 12, 1886. It was a secret that Connolly took to his grave.

Connolly has also appeared in some reference books as Joseph Aloysius Connolly. According to both state and church documents, his name was Joseph Francis Connolly, Francis being his father’s middle name. Given his Roman Catholic background, the most plausible explanation for Aloysius is that Joseph accepted this name when he received the sacrament of Confirmation on September 21, 1902. It was then an accepted practice to take a saint’s name during the liturgical rite and to incorporate it into one’s identity. Baseball annals for the most part refer to Connolly as Joe. Further, his sons said (and Rhode Island newspapers of the period concur) that Connolly preferred the nickname “Joey.”3

As a youngster, Joey participated in the family’s farming chores. His brothers often played baseball with him either on the farm or in the neighborhood. Joseph also found time to play in Manville, later joining a mill league team and eventually climbing to the semipro level. The right-hander pitched for a number of independent clubs, primarily for the Putnam, Connecticut entry in the New England League during 1906-07. His pitching impressed Frank Rudderham, a former National League umpire from Providence, who recommended Connolly to manager Michael Finn, manager of Little Rock in the Southern Association. According to the Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Evening Times, Rudderham said Connolly, “had the best curves he ever saw in his life, even after doing big league service.”4

In a 1908 spring-training outing for his new team, he lost 4-0 to Christy Mathewson and the New York Giants, having hurled a complete game. The pitcher’s persona was quiet and “Joey did not smoke, chew, nor drink,”5 habits he avoided his entire life. One reason for this lifestyle was that some of his older brothers suffered from alcoholism.6 After registering a 2-5 record during the first two months of the season at Little Rock, Connolly was sent to Zanesville, Ohio, of the Central League where he achieved an impressive 15-8 slate. He also hit .333 in 78 at-bats—the first hint that his future lay in hitting baseballs instead of pitching them.

In 1909 Connolly pitched at Little Rock for two months, then returned to Zanesville, compiling a combined 9-5 season log. He had some limited outfield play at Zanesville and batted .308. Renewing his Zanesville contract in 1910, Joey won 16 games while losing 17 for a team that finished 16 games below .500. His accomplishments included throwing a no-hitter, a one-hitter, a two-hitter, and four three-hitters. The left-handed batter hit .255 in 169 at-bats. Central Leaguers nicknamed him “Old Hickory Jerkey” because of his unusual delivery.7 The latter, combined with “a fine assortment of speed and curves, made him a cracker jack hurler.”8 Two factors hindered his progression. First, scouts thought he was too small (he stood only 5 feet 7½ inches and weighed 165 pounds), and second, he was experiencing arm trouble.9 Various people advised him to return to farming.

Connolly’s major-league ambition in jeopardy, he remained in Zanesville for the 1911 campaign and insisted on playing the outfield full-time. This was a dramatic change at the age of 27. Manager Joe Raidy resisted this request and limited Connolly’s playing time. The demand for a trade and team financial problems led to his being sent to Central League rival Terre Haute. In his first few games there, Connolly “misjudged flies and booted grounders like a rank amateur.”10 But he never gave up on himself and his fielding, running, and hitting improved as he won the league’s batting crown with a .355 average and stole 27 bases. This proved to be his big break, with five teams bidding for his services. Terre Haute sold Connolly to the Cubs, who in turn traded him to Montreal of the International League. In 1912 at Montreal Connolly hit .316. Having established his credentials, he was drafted by the Washington Senators. Despite having a good spring in 1913, he was sold to the Boston Braves.

Manager George Stallings made Connolly his regular left fielder in 1913, even though he often sat him down against left-handed pitchers throughout his career. Though his first major-league season ended prematurely when he broke his ankle while sliding, the 29-year-old rookie led all Braves regulars with 79 runs scored, 57 RBIs, 11 triples, a .281 batting average, and a .410 slugging average. He also stole 18 bases and tied Les Mann with a team-high 34 extra-base hits. As for Connolly’s hitting strategy, it included adapting an at-bat to a pitcher’s style. If a hurler threw a spitball, Connolly would chop down on the delivered pitch. In another situation, when Connolly first faced Grover Cleveland Alexander, he was outmatched by Pete’s “baffling hooks.” Thus, on one occasion, he rushed forward and swung before the ball broke. A furious Alexander yelled, “Listen kid, if this ball isn’t coming at you fast enough, just let me know.”11 From that day on Alexander threw him only fastballs, which Connolly preferred. One of his 14 career major-league home runs was off the Hall of Famer.

The 1914 Miracle Braves owed their success to players like Connolly. The sportswriters often referred to him as “slugger” or “star.” Boston’s only regular to hit .300 (.306), he was also the team leader in doubles, home runs, extra-base hits, total bases, and slugging average (third in the National League at .494). Manager Stallings demonstrated his high regard for Connolly by having him hit third in the lineup and by reportedly betting several suits that he would out-hit Philadelphia’s Home Run Baker in the World Series. The manager’s prediction did not come to fruition as Connolly was limited to one hit (.111) in the Series while Baker finished at .250. Nevertheless, Stallings’ respect was further highlighted by a comment made after Game Three of the World Series. On the occasion of a fielding play, Stallings commented that “Connolly showed a remarkable instance of pure grit when he went head-first into the left-field bleachers in a fruitless attempt to get [Stuffy] McInnis’ two-bagger.”12

As a member of the world champions, Connolly was the guest of honor at a number of banquets scheduled throughout Rhode Island. Because of his personality and baseball connections, he had been designated a “native son” by several communities. Joey Connolly Days were celebrated in Putnam and Manville. In recognition of his accomplishments, the Braves outfielder was presented with loving cups at both localities. The Manville reception was the apex of Connolly’s victory tour. Rhode Island dignitaries, including Congressman Ambrose Kennedy who gave the testimonial, attended it. Joey was “a hero in his own hometown,”13 but he was also recognized on the national scene. Baseball Magazine described Connolly as “the bearer of universal good cheer, the most pleasant, genial, likable person in baseball today.”14 The article labeled him as “the man who always smiles” and “Stallings’ heavy slugger.”15

The Braves challenged unsuccessfully for the pennant during the 1915 and 1916 seasons. In 1915 Connolly hit .298 but his slugging average dropped nearly 100 points (.397). Despite this downturn in power, he still led all Braves regulars in both categories. The drastic change in offensive statistics by Connolly and his teammates was the result of moving from the South End Grounds to the more spacious new Braves Field. The following year, Connolly’s production and playing time decreased dramatically. He hit a meager .227 in just 110 at-bats. Boston’s contract offer for the 1917 season slashed his salary in half. When the outfielder refused to sign, he was sold to Indianapolis of the American Association. Realizing that his combined income from farming and playing semipro ball locally would exceed that from his major-league contract, he retired.

Connolly began a new phase in his life. On October 25, 1916, he married Manville resident Mary Delaney at St. James Church in Manville. They had three children, Doris, Joseph, and Edward. Besides farming, Connolly continued to play semipro baseball in the Blackstone Valley until around 1928. He coached and managed at the semipro, college, and sandlot levels. Other endeavors marked his life. He was an active member of his church, dedicating his time to Catholic youth activities. An ardent sportsman, Connolly was the founder and first president of the Sayles Hill Rod & Gun Club. On the political front, even though North Smithfield was a Republican enclave, Connolly, a Democrat, won election to the town council and later was elected as a state representative (1933-34) and as a state senator (1935-36). Beginning in the mid-1930’s, Connolly was employed as an investigator by the Rhode Island State Board of Milk Control.

On September 1, 1943, Connolly suddenly became ill and died at home, the cause of death being listed as coronary disease.16 A local headline read, “Joey Connolly Called Out By Great Umpire.” 17 Throngs, including church and state dignitaries attended the funeral. The relationship “Old Joey” had with the local communities was confirmed by the fact that the lifelong Sayles Hill resident died there, his funeral was at St. James in Manville, and he was buried at St. Charles Cemetery in Blackstone, Massachusetts.

Having baseball talent, Connolly nevertheless worked hard to refine his skills. Although he achieved success throughout his life, he always remained humble and unpretentious. He shunned the nightlife but enjoyed socializing. During Connolly’s major-league days, Sunday baseball was prohibited in Boston, so his teammates would often join him at his farm. Connolly was also a man of principles. When a situation appeared unfair to him, he acted accordingly. He left the Braves over a salary dispute and he resigned as Providence College baseball coach in 1924 over faculty interference. In the latter situation, the friction was primarily with Father Ambrose Howley, the athletic director. Connolly did not believe his services were needed by the college “since there were enough coaches on the field already.”18

He helped found the Carney Sandlot Baseball League. Upon his death, the league suspended play several days “in reverence to the memory of Joey Connolly.”19 He had recently attended a game and observed his son, Joseph Jr., lash out three hits. Dedication to his family was always a priority. When the children were going through their father’s belongings, Joseph Jr. relates that they found about ten of his hunting licenses. “And you know,” said a smiling Joseph Jr., “his age on those licenses never changed—he never got older!”20

A version of this biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Potomac Books, 2004), edited by Tom Simon. It is also included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Woonsocket Evening Call, October 5, 1914.

2 Taped interview with sons Joseph Connolly Jr., and Edward Connolly, July 21, 2001. Interview tape is available from SABR’s Oral History Committee.

3 Ibid.

4 Pawtucket Evening Times, February 19, 1908.

5 Woonsocket Evening Call, October 7, 1914.

6 Taped interview with family members, July 21, 2001.

7 National Baseball Hall of Fame player file, unidentified newspaper article, November 1914.

8 Ibid.

9 Height and weight as listed in the Baseball Encyclopedia (2004); an unidentified November 1914 newspaper article in Connolly’s Hall of Fame player file lists Connolly as 5 feet 6 1/2 inches.

10 Hall of Fame player file, unidentified newspaper article, November 1914.

11 Woonsocket Evening Call, September 3, 1943.

12 Woonsocket Evening Call, October 14, 1914.

13 Pawtucket Evening Times, October 30, 1914.

14 Samuel M. Johnston, “Good Natured Joe Connolly, The Man Who Always Smiles,” Baseball Magazine, February 1915, 25-26.

15 Ibid., 25.

16 Death Certificate; Rhode Island Department of Public Health.

17 Woonsocket Evening Call, September 2, 1943.

18 Providence College Archives, undated article.

19 Woonsocket Evening Call, September 2, 1943.

20 This is from an additional interview with Joseph Connolly Jr. on September 1, 2001.

Full Name

Joseph Francis Connolly

Born

February 1, 1884 at North Smithfield, RI (USA)

Died

September 1, 1943 at North Smithfield, RI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.