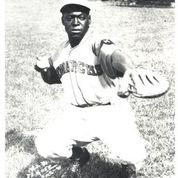

Joe Greene

James Elbert Greene, who went by the first name Joe, was one of the iconic catchers of the Negro Leagues. Greene was born on October 17, 1911, in Stone Mountain, Georgia, an Atlanta suburb. The 5-foot-11, 190-pound Greene was a durable and solid receiver who caught Satchel Paige and the balance of the elite pitching staff of the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1940s. Behind the plate, he had a strong throwing arm and a quick release that he utilized effectively to cut down runners attempting to steal. At bat, he was a right-handed pull hitter with excellent power who hit for high average in his prime. His principal drawback as a player was his lack of speed on the basepaths.1

While little is known about Greene’s early life, his mother, Emma Green, appears to have been working as a washerwoman at the time of his birth. By 1920, Emma Green was the head of her household and was employed as a cook for a private family.2 Greene also had a brother, Henry, who was two years his senior. Joe attended school only through the fifth grade, and then likely already began to work to help his mother and brother pay for their family’s expenses.

Historian Phil Dixon asserts that Greene broke into semipro ball with the Macon Georgia Peaches.3 In 1932, at 21 years old, he made his debut in professional baseball, with the Atlanta Black Crackers of the Negro Southern League; it was the only year the Southern League was regarded as a Negro major league. The young and solid Greene was quickly nicknamed “Pig” for the quantity of food he consumed.4 He began as a first baseman, but manager Nish Williams suggested, “You’re big, got good weight on you, but you throw like a catcher. Can you catch?” As Greene told the story, “I said, ‘I’m not scared to get back there, but I don’t know how to catch. If you teach me how to catch, I’ll catch.’ … I figured right quick if he was managing the ball club and if he was an ex-catcher, I’d have a better chance than anybody on that team of getting all the information I wanted. … And I went up as a catcher because I always studied.”5

Although like most Negro Leaguers he occasionally filled in at other positions,6 it was as a catcher that Greene spent the bulk of his career and made his mark. He was with the Atlanta Black Crackers from 1932 through 1938. The Black Crackers sometimes played after 1932 as a member of the Negro National League, often as an independent barnstorming unit, and later as a member of the Negro American League. Because of the scanty offensive records available for this era, statistics have been uncovered for only 49 league games played by Greene with the Black Crackers, in which he hit .236 with 14 RBIs. Among the pitchers he caught early in his career was Roy Welmaker, who went on to star for the Homestead Grays.7 Black Crackers shortstop Pee Wee Butts regarded Greene as one of the outstanding defensive stalwarts on the team: “Big [Joe] Greene … had a good arm, could throw, could get the ball to you on time so the runner wouldn’t have a chance to go through his act and spike you or something like that.”8

In 1938 Atlanta joined the NAL and Greene’s batting provided the charge needed to win the second-half title.9 Greene batted .280 with a .782 OPS. Negro League historian James Riley has deemed Greene the NAL Rookie of the Year for his 1938 campaign.10 Greene also played in the 1938 NAL Championship Series against the Memphis Red Sox. Over the course of the two-game series, which was swept by Memphis, Greene went 0-for-6 at the plate but maintained a perfect fielding percentage.

In 1939 the Black Crackers disbanded, and Greene was picked up by the Homestead Grays, where he roomed with future Hall of Famer Buck Leonard, who became his mentor. According to Leonard, “Greene was big, strong, had a great arm. He couldn’t hit a curve ball, but he could hit a fast ball for miles. So we bought him an extra-long bat, a thirty-seven-inch bat. Then he could just get a piece of that curve ball.”11 When Josh Gibson joined the Grays as a catcher later in 1939, Greene got his big break as he was traded to the Kansas City Monarchs, where he remained through 1947.

In the early 1940s the Monarchs were the top squad for backstops to be on. They featured a stellar starting pitching lineup that included future Hall of Famers Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith, and Connie Johnson. When Johnson pitched to Greene, they were called the Stone Mountain Battery since Johnson was also from Stone Mountain.12 According to Hilton Smith, Greene, who had turned himself into a strong curveball hitter, was an important catalyst for the Monarchs dynasty of that era: “We picked Joe Greene up as catcher in ’39 and about the middle of the season he was really hitting that ball. In ’40 he really whipped that ball.”13 Greene became the principal catcher for the great Monarchs franchise, which won league titles every year Greene was on the team between 1939 and 1946.14 He also was part of a self-described “syndicate” of Monarchs players who demanded disciplined behavior and winning ways. They weeded out players who did not share those values.15

Hilton Smith once recalled: “I was telling a fellow today about Greene when he used play Cleveland when Sam Jethroe was there. [Jethroe was reputedly the fastest man in black ball at that time.] They told Greene, ‘Well we’re going to steal on you today. We’re going to beat you, we’re going to bunt and get on, then we’re going to steal second, we’re going to steal third, we’re going to bunt in runs. … I was pitching and only six men got on [base] that day. … [S]ix of them tried to steal and he threw out five of six. … They’d get on, they’d try to go down, that’s as far as they’d get. That guy could sure throw.”16 According to Greene, he carefully studied runners on the bases and coordinated closely with pitchers to catch players attempting to steal. He was so obsessed that he even dreamed at night about players trying to steal on him.17

Once he had become an established veteran, Greene’s nickname morphed into “Pea” in tribute to the fact that he threw “peas” to second base.18 Hilton Smith continued, “In ’41, that’s when Greene really came into his own. That year and the next year, ’41 and’42, you can believe it or not, that guy in my opinion was the best catcher in baseball. In ’42. … [T]hat man hit that ball that year. And threw out everybody. He was a great catcher those two years.”19

Records bear out Smith’s words. Usually batting fifth for the Monarchs behind Hall of Famer Willard Brown,20 Greene led the Negro American League against all levels of competition in 1940 with 33 home runs.21 In 1941 Greene’s batting average against all competition was .313 as the Monarchs took the NAL pennant.22

Historian John Holway credits Greene with a .366 batting average in 1942, a year for which Holway has awarded Greene his Fleet Walker Award as the MVP of the NAL. In 1942 he again led the league with 38 home runs against all competition.23 Dixon states that Greene joined an elite club in 1942 by hitting four home runs in one game, and that he drove in 15 runs in six consecutive games.24 Buck Leonard later acknowledged that the Homestead Grays made a big mistake by giving up on Greene too early because “he turned out to be a great ballplayer.”25

The power-hitting Greene always claimed that the Ted Williams shift was developed for him in the Negro Leagues by manager Candy Jim Taylor and then adopted by the major leagues after they saw it used against him.26 Like Ted Williams, Greene was an extreme pull hitter who ignored the shift and just hit over it: “I hit the ball too hard for them. … In Kansas City, center field was 400-something feet. Oh, my God, you’ve got to drive a ball almost 500 feet to get it out of center field over that wall. I hit over the scoreboard in left-center field. I’ve hit lots of long home runs in Chicago’s Comiskey Park way up in the stands. I hit a couple long ones in Yankee Stadium. … Josh Gibson and I were the two most powerful hitters as catchers.” 27

In the 1942 Negro League World Series, Greene’s Kansas City Monarchs opposed Josh Gibson’s Homestead Grays. Greene regarded himself as Gibson’s equal and asserted, “Well, you’ve been talking ’bout the great Josh. I’m gonna let you know who’s the great one.”28 Greene hit .500 with a home run to lead his team’s offense to a four-game sweep of the Series. Gibson batted .077 with no home runs. Greene was Satchel Paige’s catcher in the Series’ classic confrontation between Paige on the mound and Gibson at the plate. In one at-bat, Paige, always the showman, announced to the crowd in advance the type of each pitch he would throw Gibson, and then struck Gibson out on three straight pitches, marking one of the legendary moments in Negro League history.29

Greene was named to three East-West All-Star Classics between 1940 and 1942, by which time he had become regarded as the best catcher in the Negro American League.30 Seamheads.com, which has designated the single best catcher for each Negro League season based upon WAR,31 has named Greene the NAL All-Star catcher in 1940, 1941, and 1942.

Greene capped 1942 by going 2-for-4, including a game-winning double, to lead his team to a 2-1 win over a team of Dizzy Dean-led white big leaguers in the armed forces before 29,000 fans in Wrigley Field.32 Greene claimed his trick for hitting white major-league pitchers was that they often pitched low and he was a good low-ball hitter. According to Greene himself, “Sometimes they’d say, ‘Joe Greene, you were on your knees when you hit that.’ Sometimes I would go almost down on my right knee. But I’d hit it in the stands.”33

In 1943, when he was at his peak ability as a player, Greene was inducted into the US Army and served three years during World War II. He was assigned to the all-black 92nd Infantry Division, the “Buffalo Soldiers,” whose motto was “Deeds Not Words.” As a member of the only African American division that saw combat action in Europe or North Africa during World War II, Greene fought in Oran, Algiers, and Italy. He was on the front lines for eight months. Greene was in a 57mm antitank company that opened up the third front in Italy. His harrowing job consisted of close-range combat against German tanks. Wounded by a shrapnel blast in Italy, he returned to combat after three weeks in the hospital and was awarded two battle stars. As his division drove into Milan, it was his military unit that discovered and cut down the bodies of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress following their deaths at the hands of partisans.34

Yet his war experience left time for baseball after hostilities ended. Greene headed the 92nd Division team as it won the baseball championship of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. Greene’s team then played in the G.I. World Series in Marseilles where, combined with another African American division containing Willard Brown and Leon Day, the team, sparked by home runs by Greene and Brown, crushed Third Army squad, 8-0.35

In 1946 Greene went back to catching for the Monarchs as they again won the pennant. Holway has deemed him the 1946 All-Star catcher for the NAL.36 According to James Riley, Greene was able to record batting averages of .300, .324, and .257 against all competition from 1946 to 1948.37 In 1947 he blasted 16 home runs in 49 games.38 The New York Yankees scouted Greene in the 1940s but nothing came of it.39 The Yankees’ first African American player was Elston Howard in 1955. Buck O’Neil, who discovered Howard, once observed that Greene, when he first came up in 1938, was a superior catcher to the young Howard.40

The following year featured one of Greene’s career highlights when, at the age of 35, he hit a long home run off Bob Feller in an exhibition game in Los Angeles on November 2, 1947 (a nine-inning duel in which Satchel Paige bested Feller with a shutout).41 The Los Angeles Times called Greene’s blow a “resounding homer.”42

But the hard truth is that Greene never really regained his prewar form.43 In 1948 he was traded to the Cleveland Buckeyes, where he ended his Negro League career with only a .143 batting average in NAL games. He accumulated no WAR in official league games from 1946 through 1948 and his lifetime batting average fell to .242. All that was left was his power as his 1948 home-run percentage in limited plate appearances was a remarkably high 7.1 percent.

As the Negro Leagues went into a death spin after Jackie Robinson entered the major leagues, Greene followed other players to Canada. He finished his playing days at the age of 39 with one season in the independent ManDak League, hitting .301 with 16 RBIs in 1951 for the Elmwood Giants.44

After he retired as a player, Greene and his wife settled in Stone Mountain, where he worked for years at Sears Roebuck.45 He was active in his community as a member of the local African American men’s club.46 Greene died in Stone Mountain on July 19, 1989, at the age of 77. He was survived by his wife, Emma S. Greene; the couple had no children. The funeral service was held at the Bethsaida Baptist Church in Stone Mountain and Greene was buried in Stone Mountain City Cemetery.47

As a player, Joe Greene’s importance should not be understated. He was an MVP, two-time home-run champion, Negro League World Series champion, and repeated All-Star who was responsible for handling Satchel Paige and the remarkable Kansas City Monarchs pitching staff during their multiple pennant runs in the 1940s. Even though he lost three years of his prime career to World War II, his OPS+ of 120 (many statisticians believe OPS+, which combines on-base-percentage plus slugging adjusted by ballpark and era, is the best overall measure of offensive performance)48 stands as the fifth highest among catchers in American Negro League history. Greene’s OPS+ rating for catchers in Negro League play is exceeded only by the four Negro League catchers inducted into the Hall of Fame (Josh Gibson, Louis Santop, Roy Campanella, and Biz Mackey).

Greene’s WAR per 162 games of 3.3, established over the 12 years he played league ball, is the seventh highest established by any catcher in Negro League history. Bill James ranks Greene as the eighth best catcher of the Negro leagues.49 Pitcher Jim “Fireball” Cohen, a Negro League All-Star who played at the tail end of the Josh Gibson era, chose Joe Greene as the number-one catcher on his all-time team.50

Ultimately, Greene’s legacy is far larger than his on-field performance. He was a decorated war hero in a segregated army who fought alongside white soldiers. Since he also played against white major leaguers, he had a solid perspective from which to assess the overall quality of baseball at the highest levels. Greene become an advocate for Black ball and an outspoken spokesman for the quality of the Negro League game. In the 1940s Greene convinced leading sportswriter Fay Young of the Chicago Defender that the tryouts given to African American players prior to Jackie Robinson were a sham.51 He forcefully declared that he and his African American brethren, not just Jackie Robinson, were the true pioneers who had paved the way for integration. He noted in a matter-of-fact manner that Robinson was not the best player the Negro Leagues produced, but simply representative of the excellence of Black ball.52 According to Joe Greene, who played against them all, the Negro Leagues were “the real Major Leagues.”53

Sources

Ancestry.com was consulted for census, military service, and death information.

Seamheads.com is the leading source for official Negro League game statistics. Other major historians, such as John Holway and James Riley, include all statistics against all opposition, including exhibition games, games against semipro teams and teams from other Negro Leagues, etc. John Holway believes that, as the majority of games played in Black ball were outside of the official league games, his approach is more indicative of the full Black baseball world. While there can be major discrepancies between the data gathered using these different approaches, both methods have value. In this article, completed early in 2021, Seamheads is the basis for player and team statistics cited in this article, except where otherwise indicated.

Notes

1 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 337.

2 His father may have been a Charlie Green, who is listed in the 1910 census has having been married to an Emma Green in Thomasville, Georgia; the name and birth year for Emma fit with Joe’s mother, but that alone is not enough to positively state that this Charlie and Emma Green were his parents. In the 1940 census, Emma Green was listed as a widow. If Charlie Green was Joe’s father, he may have died or abandoned the family at some point since he was not listed as part of the family unit in the 1920 census. It should also be noted that census takers consistently misspelled Joe Greene’s family name as “Green.”

3 Phil S. Dixon with Patrick J. Hannigan. The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History (Mattituck, New York: Amereon, 1992), 225.

4 Riley, 337.

5 John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Rev Ed., (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2010), 302-303.

6 In the seventh game of the 1946 Negro League World Series, Greene was pressed into serviced as a right fielder when outfielders Willard Brown and Ted Strong failed to show up until the game was almost over because they were busy negotiating winter contracts. Satchel Paige, who was scheduled to start the game, did not bother to show up at all. See Buck O’Neil, with Steve Wulf and David Conrads, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 177.

7 Dixon with Hannigan, 225.

8 Holway, Voices, 331.

9 Riley, 337-338.

10 Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer, eds., The 2006 ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2006), 1649.

11 Holway, Voices, 299.

12 Frazier Robinson, Catching Dreams: My Life in the Negro Baseball Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 59.

13 Holway, Voices, 300.

14 Aside from 1943 when Greene played in only two league games before he was called into the military. The team, denuded of much of its talent by the war, did not win the pennant that year.

15 Holway, Voices, 304-305.

16 Holway, Voices, 300.

17 Holway, Voices, 303-304.

18 Buck O’Neil, 119-120.

19 Holway, Voices, 300.

20 Riley, 337.

21 Riley, 337.

22 John B. Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History (Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House, 2001), 383.

23 Riley, 337.

24 Phil S. Dixon, 1987 Negro League Baseball Card Set, card #8.

25 Holway, Voices, 299.

26 Holway, Voices, 301.

27 Holway, Voices, 301.

28 Holway, Voices, 300.

29 O’Neil, 133-135.

30 Riley, 337.

31 WAR (Wins Above Replacement) is a measure of a player’s value based upon all facets of his performance and measures how many wins the player is worth versus an average replacement.

32 Holway, Complete Book, 401.

33 Holway, Voices, 304.

34 Timothy M. Gay, Satch, Dizzy & Rapid Robert, The Wild Sage of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 192-193.

35 Gay, 191-192.

36 Holway, Complete Book, 434.

37 Riley, 337;

38 Holway, Voices, Appendix.

39 Holway, Voices, 307; Gay, 252.

40 O’Neil, 189.

41 Gay, 258; Holway, Complete Book, 452.

42 Holway, Voices, 300.

43 Holway, Voices, 300.

44 Barry Swanton, The Mandak League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2006), 108.

45 Holway, Voices, 309-10.

46 Dixon and Hannigan, 179.

47 Atlanta Constitution, July 23, 1989: 40.

48 OPS+ (On-Base Plus Slugging Plus) is a version of On-Base Percentage Plus Slugging, normalized by accounting for external factors such as ballpark and era. See Anthony Castrovince, A Fan’s Guide to Baseball Analytics (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2020), 56-60, 76-81.

49 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 181.

50 Larry Lester. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 481.

51 Holway, Voices, 307.

52 Holway, Voices, 312.

53 Holway, Voices, 310.

Full Name

James Elbert Greene

Born

October 17, 1911 at Stone Mountain, GA (USA)

Died

July 19, 1989 at Stone Mouintain, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.