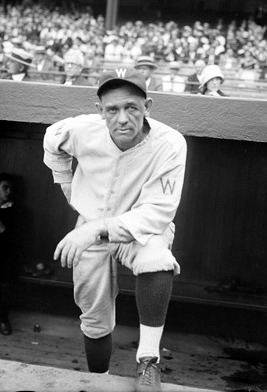

Joe Harris

There were two major-league ballplayers named Joe Harris, and both played for Boston’s American League team. They had very different records. One had two middle names – the pitcher named Joseph Lionel White Harris, who pitched only for Boston (1905-07) and racked up the astonishing record of 3-30, despite a 3.35 earned-run average. This biography looks at the one with no middle name: Joseph Harris, a first baseman and outfielder who played for six teams from 1914 through 1928 (with the Red Sox from 1922 into 1925), and hit for a career .317 batting average. With the Red Sox, he hit .315. Like many ballplayers, he might have played even better if he’d been used regularly, and at a predictable position in the field. He played at his best when he was at first base, recording a .989 fielding percentage at that position.

He did have a nickname, “Moon,” a legitimate one reported as such by his widow, Pearl, on a questionnaire she completed for the Hall of Fame not long after Joe’s death.

This Joe was born in Coulter, Pennsylvania, in the southwest part of the state about 10 miles up the Youghiogheny River from McKeesport, on May 20, 1891. He was the 10th of 11 children of Joseph and Annie Harris. The Harris family was living in South Versailles township, in Allegheny County, in 1900 and Joe the elder worked as a coal miner. Harris had emigrated from England and Anne Hodges Cherry from Scotland; they married in Coulter in 1870. They’d be in no rush to name a son after the father – the children were Enoch, Mary, John, Alexander, Elizabeth (who died at 4 months), Margaret, David, William, James, Joseph, and Thomas. All but Alexander lived at home in 1900, ages ranging from Enoch at 28 to Thomas at 6.

Most of the men worked in the coal mines. Father Joseph was doing “odd jobs” in 1910 and was retired at age 82 in 1927. The younger Joe became a ballplayer. His formal education consisted of eight years in the Coulter public schools. He never attended high school. He played with a number of town teams but his first professional experience in baseball had been with McKeesport in the Ohio-Pennsylvania League, playing in a single 1908 game shortly before his 17th birthday.1

The next record of him playing professionally is as a regular for the McKeesport Tubers in 1912. McKeesport loaned Harris to the Louisville American Association team for 10 days, after which he returned to McKeesport. The McKeesport team folded before the end of the season.2

In May 1913, the Bay City Times reported, “Joseph Harris, a hitter and also a fielder of some repute, was purchased by Manager Shannon of the Beavers and arrive here today. Harris was with the McKeesport club of the O&P league last season and while there gained a reputation as a hitter. His average in this department of the game was .375, this average leading the league. During the past spring he worked out with a team in Kentucky.”3

Harris completed the 1913 season with Bay City in the Southern Michigan League, and had begun to make his mark as an infielder. He was right-handed, stood 5-feet-10½ and is listed with a playing weight of 175 pounds. He hit .329 in 89 games as Bay City’s first baseman in 1913 and led the league’s first basemen in fielding percentage (.992), committing only five errors.

The New York Americans (the Yankees) signed Harris for a trial and gave him a look in 1914. He got his first taste of the majors, debuting for manager Frank Chance and the Yankees in two June games in 1914. He was signed on June 8 as New York played a series in Chicago, the New York Times reporting, “It is common gossip that Chance is not satisfied with the work of Frank Truesdale at second base.” The same brief note on the signing quoted Chance: “I won’t use Harris right away, unless there is a call for his services. I’ll look him over in practice a few days, and if he looks promising he will get a chance to show cause why he should be retained.”4

There was a call for Harris’s service the very next day. By the fourth inning, the White Sox had already scored six runs, helped by four Yankees errors, every one of which helped produce a run. Left fielder Jimmy Walsh was replaced in mid-game (one of the errors had been his) and Harris took his place. He appeared twice at the plate, striking out on three pitches in his first major-league at-bat and then being hit by a pitch his second time up. “He handled himself well in the garden,” wrote the Chicago Tribune, “and displayed an excellent whip when he nearly nailed [Eddie] Collins at second in the seventh.”5

The very next day, Harris played again, in St. Louis, this time at first base against the Browns. He had a remarkable day; he was without a hit in four plate appearances, but actually acquitted himself perfectly – he drew bases on balls the first three times up and then executed a sacrifice bunt, reaching all the way to third base on a St. Louis error. He was then removed for a pinch-runner. He never scored a run. New York won, 5-3. The road trip continued, but when the Yanks returned to the East, Harris was no longer with them. “Chance evidently found something wanting in the young fellow and silently dropped him.”6

Harris was “turned back” to the Bay City Beavers and played out the season, mostly at first base but with 24 games in the outfield. He collected 197 base hits, batting .386, leading the Class C league in both categories and helping Bay City place first in the 10-team league standings. He stole 42 bases, showing he had some real speed, also evidenced by his league-leading 22 triples.

Harris was drafted by the Chattanooga Lookouts (Southern League, Class A) and played first base exclusively in 1915, batting a disappointing .258 in 155 games. He repeated with the Lookouts in 1916, upping his average to .309. This secured him a job with the Cleveland Indians for 1917.

At the recommendation of scout Bill Rapp, Cleveland drafted Harris from Chattanooga and he played in 112 games, 95 of them at first base, supplanting the much-hyped Lou Guisto at the position.7 Guisto was the promising prospect, from the Portland Beavers, but he showed up overweight and Harris’s versatility in the field proved a virtue and earned him a slot on the team. It wasn’t until Harris’s ninth game, however, that he finally got his first major-league base hit. After eight pinch-hitting appearances (resulting in three walks), he finally got a start – on May 29 against the visiting Detroit Tigers. He got two hits in five at-bats, a single his first time up. His second hit was a double to right field that drove in the winning run – the only run of the game – in the bottom of the 10th inning, scoring Tris Speaker for a 1-0 victory.

Harris earned his keep, batting .305 and – despite getting into only three-quarters of the games – finished second on the team with 65 RBIs, only seven behind Braggo Roth’s 72. He had a .985 fielding percentage. He had “exceeded all expectations.”8 Then came the World War. On August 15 Harris was examined by the draft board in Cleveland and accepted for service in the Army. He played out the season but in February 1918 reported to Camp Lee in Virginia and by June he was in France as a private with the 320th Infantry of the 80th Division. By November he had earned a promotion to sergeant. He’d seen combat. A letter to Henry P. Edwards of the Cleveland Plain Dealer told of 15 days in the trenches, on the front lines, once being caught in a shell hole between “our barrage and the Jerrys … but I guess God was with me.” He said he’d had the opportunity to go to officers’ training school “but I think I will stick to the boys I am with now.” He signed the letter “Sergeant Moon.”9 On another occasion, the man next to him – a lieutenant – was cut down by German machine-gun fire and Joe had to climb out from under his dead body.10

With the war over, Harris was eager to get back to baseball, but it took a while to get mustered out. He was still in Europe when an auto ambulance overturned as it took him and seven other soldiers to board a train for an embarkation camp so they could head back home. Harris was the most seriously injured, knocked unconscious with a laceration near his eye. He was confined to a military hospital in Tonnere, France, for a full month; he had suffered a skull fracture, three broken ribs, and severe bruises on his legs. A report in the Washington Evening Star said, “It is doubtful that he will ever be able to play ball again.”11 Harris had a different opinion.

Harris returned to the United States on May 24, to a military hospital in New York. He rehabilitated and got into his first game on the last day of June. On July 1 he served notice that he was back, with a 3-for-5 day (one hit off each of three White Sox pitchers); he went 9-for-20 over his first five full games.

Harris played exceptionally well for someone who had been out of the game for well over a year and a half. He played in 62 games and hit for a .375 average, with 46 runs batted in, a pace of 115 for a full season. In the first game of a September 10 doubleheader against the Yankees, he drove in all three runs of the 3-0 Indians win. His fielding ticked up a notch, too, to a .988 percentage at first base.

Harris seemed perhaps poised for greatness, but come wintertime he was dissatisfied with the $5,000 contract he was proffered and decided to hold out for a better one. Shortly after the 1919 American League season, Harris (along with George Sisler) had played a few games with the Franklin, Pennsylvania independent team. The Franklin ballclub matched the Indians offer and “set me up in business, too.”12 He went with it. Basically, it was a better deal. Harris said he was making more with Franklin than he had been offered by Cleveland.13 As to the business, the Franklin News-Herald reported, “[Harris] joined Homer D. Biery and Lawrence D. Gent in leasing the Commercial Hotel. Harris and Gent utilized the first floor as a billiard and pool room and it became a congregating place for baseball fans…He continued to maintain his business interest here and spent much time in Franklin during the 1920s. In the mid 1920s he sold his interest in the pool room to Florence Murray.”14

Harris played the year for Franklin, 149 games for the “outlaw” team, and cashed his salary checks, but he missed out on something: the Cleveland Indians won the American League pennant for manager Tris Speaker and beat the Brooklyn Robins in the best-of-nine World Series, five games to two. Doc Johnston was a more than adequate replacement at first base.

In February 1921 Harris married Franklin native Pearl Hepner. They resided in Franklin in the offseason until Joe’s career ended in 1931. The couple remained married until Joe’s death separated them in 1959.

Harris wanted to join Cleveland in 1921,15 but the team still wasn’t offering to go above $5,000, and Joe’s application for reinstatement was either denied or not acted upon, so he played for Franklin again, batting for a .407 average but the team folded in July and Harris finished the season with other teams outside Organized Baseball, at Clearfield16 and Hornell. That autumn, Harris again applied to Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for reinstatement. As he awaited the commissioner’s ruling, Harris was traded – on December 20 – to the last-place Boston Red Sox (along with George Burns and Elmer Smith) for Stuffy McInnis. The trade was conditional on Harris’s reinstatement. At first it seemed that his petition would be denied, but it ultimately came to pass, on February 4. Landis cited Harris’s war service as something that earned him special consideration. Noting that Harris had been gassed and shot at in the war, he more or less said that his experiences might have caused him “to do things which he otherwise might not have done.”17

Hugh Duffy was the Red Sox manager. He had Harris play the outfield (Burns played first base) and Harris led the team in batting, hitting .316, and led as well as in on-base percentage and slugging, despite being shifted around here and there – even helping Burns out in 21 games at first base. He also suffered a very bad spiking in midseason. The Red Sox finished last again.

Leading the team in hitting had been Harris’s goal. When Boston owner Harry Frazee sent Harris his contract over the winter, Harris asked for $1,000 more than what he’d been offered. He told Frazee that if he didn’t bat better than everyone else on the team, he wouldn’t feel he had earned it. It wasn’t truly a wager, but it impressed Frazee, who ponied up the extra grand. Had Harris intended to return the extra thousand if he fell short became a moot question.18

Harris did say that, despite batting right-handed, he preferred to bat against right-handed pitchers.19 He was unorthodox as a fielder, too, using a five-fingered glove while playing first base.20

Harris hit even better in 1923 than he had in 1922, this time reunited with manager Frank Chance. As we recall, Harris first played briefly for Chance back in 1914. He hit .335, again leading the Red Sox in average, on-base percentage, and slugging. Burns came in second in all three categories, but he and Harris flip-flopped with RBIs: Burns drove in 82 and Harris was second with 76.

Lee Fohl was Red Sox manager in 1924, prompting another reunion. Harris had played for Fohl in 1917 and 1919. Harris was very optimistic heading into the season, believing the Red Sox had a chance to contend, and happy to be back at first base himself.21 He had to fight neuritis in the springtime and was limited in the early action. By season’s end, he had driven in one more run than the year before – 77 – and batted .301, third on the team in average – but again first in on-base percentage. This time he placed second in slugging and third in RBIs. The Red Sox finished seventh.

Harris began the 1925 season with the Red Sox, but with Phil Todt set for first base, he wasn’t expected to get quite as much work. On April 29 the Sox traded him to the Washington Senators for Roy Carlyle and Paul Zahniser. He’d assembled only 26 plate appearances for Boston and was batting .158. Sox fans were nonetheless disappointed to lose him, and the Boston Globe wrote, “He always has been a player who has given his club all he has, and, in these days, that is something unique.”22

He reverted to form with Washington, despite a scare of an elbow injury in June, and was able to step in when longtime first baseman Joe Judge had to bow out due to nagging injury.23 Harris played in an even 100 games and batted .323 – third on the team in batting average, but first in OBP and SLG. And the Senators won the pennant. The World Series ran to seven games, Washington winning three of the first four, but then the Pittsburgh Pirates winning the final three to become world champions.

Harris played in all seven games and led all batters, hitting .440 with three home runs and six RBIs. It was his single in Game Three that provided the winning hit in that game.

After the 1925 season, he had one or two operations, at least one of them on an eye. Harris hit for a .307 average with the Senators in 1926, playing in 92 games.24 Since he’d returned from the war, he’d been hitting with a bit of a handicap since the scar tissue had tightened under the eye that had been injured in the war. “This made it necessary for Harris to crouch low and look at an upward slant as pitchers heaved the ball toward him.”25 He underwent plastic surgery in Franklin to relieve him of the need to crouch quite so much.

In February 1927 the Senators sold Harris’s contract to the Pittsburgh Pirates via waivers. (He’d been put on waivers in early August 1926, and the Pirates were the only team that claimed him.)26 The Pirates planned to use him as a utility first baseman and outfielder, and he came in quite utile. Initially used as a pinch hitter, but by early May he had become the regular first baseman. In mid-June he was sporting a .446 batting average before a foot injury hampered him for the rest of the season. In all, he appeared in 129 games for the Pirates, with his average falling to .326 by the end of the season. He suffered some neuritis again, and again suffered from uncertainty regarding his position, but one assessment said “when he went to first base, his hitting lifted his Pirates back into the thick of the pennant fight.”27 Harris didn’t lead the club in anything, but was in the top four in most key offensive categories. It was a solid ballclub, winning the National League pennant (94-60) under Donie Bush in a close race with the Cardinals and Giants. The 1927 Yankees juggernaut, however, swept Pittsburgh in the World Series. Harris was 3-for-15 (all singles) with just one run batted in.

Harris began 1928 with Pittsburgh, but got into only 16 games in April, May, and early June. When he did, he could still hit; at age 37: he was batting .391 when he was traded on June 8 to Brooklyn (with Johnny Gooch) for Charlie Hargreaves. With Brooklyn he played his final 55 games in the majors. His average dropped to .236 in his last 89 at-bats.

Harris finished his major-league career with a lifetime .317 batting average and a .404 on-base percentage. The pitch he hit the best was the curveball. “Seems like those pitchers never learned,” he said. “If I made 150 hits a year, 130 of them must have been on curve balls.”28

Harris still had some more baseball in him after Brooklyn and spent at least some of 1929 playing in Sacramento (54 games, batting .342 in the Pacific Coast League). His season was cut short, and in the autumn of 1929, he was hospitalized in critical condition, and went through a series of at least five gall-bladder operations.29 In 1930 he played for the Toronto Maple Leafs, appearing in 114 games and batting.333. In 1931, his last year in baseball, he played for Toronto and then Buffalo, batting a combined .311.

After baseball, Harris took up farming about 15 miles east of Pittsburgh, and raised hunting dogs. Joe’s nephews David and Joseph relate that Joe was a co-investor in the farm with his brother William, who was responsible for its operation. Another brother, John, also lived on the property. Two other brothers, David and Thomas, also had farms in the community.30

The end of his life came in Plum Borough, Pennsylvania. Joe Harris died, after four months of suffering colon cancer, on December 10, 1959. He was survived by his widow, Pearl. Less than two years later, his great-nephew Hal Reniff, grandson of his sister Margaret, debuted as a pitcher with the New York Yankees. Reniff was 21-23 in the years 1961-67 with the Yankees and, at the very end, the New York Mets.

Postscript

Bob Harris reports that three of Harris’s brothers were said to have played professional baseball. “I’ve verified Dave pitched in two games in 1908 (Scottdale) and five in 1912 (Elmira, Traverse City), and also played two years for Bethany College in WV (1913 and 1914, after having played as a pro). Tom played for McKeesport for a couple weeks in 1912. My father says John had been a catcher in the Texas League but I haven’t been able to verify any professional record of him.”31

Last updated: December 14, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Harris’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Bob Harris for substantial additions to the family background of Moon Harris, his grandfather’s brother.

Notes

1 Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, May 11, 1908, 9.

2 A sheet of paper filed in Harris’s Hall of Fame player file shows him playing for 12 games in the Texas League in 1913 for “Dallas/Galveston.” Perhaps he played in a couple of games for Galveston, though no record has yet been found in the newspapers searched. Sporting Life appears to confirm that he may have played 10 games for Dallas in April, 1912.

3 Bay City Times, May 15, 1913. The next day’s paper reported his arrival and said he had hit 20 home runs in the O&P League in 1912.

4 New York Times, June 9, 1914.

5 Chicago Tribune, June 10, 1914.

6 Pittsburgh Sunday Post, April 3, 1927.

7 Rapp’s role was noted in the June 12, 1917, Washington Post.

8 Muskegon Chronicle, March 18, 1918.

9 Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 10, 1918.

10 Boston Herald, August 8, 1919.

11 Washington Evening Star, May 22, 1919. Harris had written a more optimistic note to the Plain Dealer, which was published on May 14, but did acknowledge, “I think I have a fractured skull.”

12 The Sporting News, December 6, 1959.

13 Philadelphia Inquirer, April 10, 1920.

14 Franklin News-Herald, December 10, 1959.

15 Pittsburgh Press, January 21, 1921.

16 Pittsburgh Sunday Post, April 3, 1927.

17 The wording was not Landis’s, but as reported in the February 5, 1922, Baltimore Sun. See also the New York Times of the same date, the story entitled, “Joe Harris’s War Record Wins Player His Reinstatement.”

18 Boston Herald, July 23, 1922.

19 Ibid.

20 See an article on Harris and his gloves in the March 18, 1924, Boston Herald.

21 See the Boston Globe of January 22 and March 6, 1924.

22 Boston Globe, April 30, 1925.

23 See, for instance, the Boston Globe, August 24, 1925.

24 Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), February 9, 1926 and Palm Beach Daily News, February 10, 1926.

25 Associated Press story in unidentified news clipping found in the Harris file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

26 Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 8, 1926. The actual transaction happened on February 5, 1927. See also Washington Post, February 5, 1927.

27 Hartford Courant, October 2, 1927.

28 The Sporting News, December 16, 1959.

29 Washington Post, October 22, 1929.

30 E-mail from Bob Harris, November 9, 2014.

31 E-mail from Bob Harris, November 9, 2014.

Full Name

Joseph Harris

Born

May 20, 1891 at Coulter, PA (USA)

Died

December 10, 1959 at Plum Borough, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.