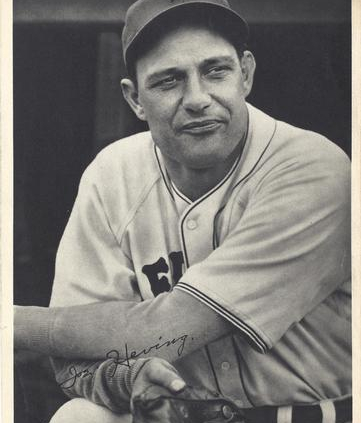

Joe Heving

Joe Heving was born four years later than his brother Johnnie, but made his major league debut 10 years afterwards. John was a catcher who played professional ball from 1919 to 1946, including five years with the Red Sox from 1924-1930. Joe Heving heaved for a living – he was a right-handed pitcher, an early relief specialist who led the league in relief work in 1939 (11 wins and just three losses) and again in 1940. During his time in major-league ball, he compiled an excellent 76-48 record, often pitching for teams that weren’t that strong. His career ERA was 3.90.

Joe Heving was born four years later than his brother Johnnie, but made his major league debut 10 years afterwards. John was a catcher who played professional ball from 1919 to 1946, including five years with the Red Sox from 1924-1930. Joe Heving heaved for a living – he was a right-handed pitcher, an early relief specialist who led the league in relief work in 1939 (11 wins and just three losses) and again in 1940. During his time in major-league ball, he compiled an excellent 76-48 record, often pitching for teams that weren’t that strong. His career ERA was 3.90.

The Hevings hailed from Covington, Kentucky, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. Joe’s daughter-in-law recalled that the Hevings had Swedish and American Indian ancestry, though both players’ questionnaires at the Hall of Fame mention only German background. There were four boys in the family: Ben (born in 1891, a carpenter), Frank (born in 1894, a saw filer), John (born in 1896, who worked as a machinist for the Maxwell Motor Co. of Newcastle, Indiana, at the time of his registration for the World War I draft), and Joe – who gave his formal name as Joe William Heving, when he himself completed his draft registration card. Joe was born on September 2, 1900, and was working as a hat tacker in a Cincinnati factory at the time of his own 1917 registration.

After the war, and service in the United States Army in 1918, it was John who first found a job playing pro ball, as catcher for the Battle Creek, Michigan, ballclub of the Class B Michigan-Ontario League in 1919. He made the majors for one at-bat in 1920, but his first full season was with the Red Sox in 1924, when he batted .284 in 109 at-bats as Boston’s third catcher. He played with Boston for five seasons, and the Athletics for two more with 1932 his final year.

An October 1936 Sporting News story says that Joe Heving had become a candy store proprietor and sold the business when he had the opportunity to play baseball. Joe began his professional career in 1923, playing in Oklahoma for the Bartlesville Bearcats in the Class C Southwestern League. He appeared in three games as a pitcher, throwing 12 innings and giving up two runs, finishing the season with a 1-0 record. But the pitching was an aberration, and he didn’t pitch again until 1926; Joe was primarily an outfielder for the Bearcats, and accumulated 428 at-bats, with a .292 average.

With Mexia in the Class D Texas Association in 1924, he struggled, hitting just .224 in 98 at-bats. Later in the year, he played for Grand Rapids in the Michigan-Ontario League, batting .281 in a limited 32 times times at bat. Joe hit .281 again in 1925, getting in a full season with Topeka of the Class D Southwestern League with 513 at-bats in 130 games. It was in 1926 that the transition occurred. Joe was again with Topeka. He hit .259 but also threw 121 innings in 16 appearances, with an 8-6 record.

In both 1927 and 1928, Joe split the season between Portsmouth (Virginia League) and Asheville (Sally League), with most of ’27 in Portsmouth (12-8) and most of 1928 with Asheville (13-5). He was just 1-1 with Asheville the first year, but 8-1 with Portsmouth in 1928, for a combined 21-6 season. He got a workout in 1929, pitching 221 innings in the Southern Association for the Memphis Chicks under manager Doc Prothro; he posted a 3.30 ERA with 14 wins against 10 losses.

The New York Giants purchased Heving in late 1929 and he made their major league roster in 1930; he was seen as a raw rookie and groomed from the start for relief work. His debut came on April 29, 1930, at the Polo Grounds and it was a terrible one. The Brooklyn Robins scored twice in the top of the first, and when Giants starter Larry Benton was roughed up in the top of the second, too (he was tagged for five hits and walked two in 1 1/3 innings), the Giants called on Hub Pruett to take over. He faced four batters and every one of them got a hit. The ball was handed to Heving, who didn’t fare much better – he gave up three hits and walked a batter and, like Pruett, never retired a man. Before the inning was over, Brooklyn was ahead 13-0. The game was a mess all the way around, though, the final score being Robins 19, Giants 15 – and so Heving’s horror perhaps didn’t stand out as much as it might otherwise have.

There were a couple of standout incidents that seaon – Heving’s nose was broken by a ball during batting practice on June 27, and on August 24 he was on the mound during another bad moment in front of a massive overflow crowd of 47,000 watching the Cubs play the Giants in Chicago. The Cubs were up 2-1 and the Giants pulled Freddie Fitzsimmons for a pinch hitter in the top of the eighth, in vain. Heving retired the Cubs in the bottom of the eighth without a fuss, and then the Giants tied it with a run in the top of the ninth. Tension built in the bottom of the ninth, until reaching the ultimate: The bases were loaded with two outs. Cubs manager Joe McCarthy let his starting pitcher, Guy Bush, bat. Heving got two strikes on Bush. Focused on the plate, he never saw Danny Taylor steal home to win the game, as he went into a windup and threw the ball just wide of the plate.

The following spring, Giants manager John McGraw had pitching coach Chief Bender work with Heving on the art of keeping runners on base. John Drebinger of the New York Times noted that Giants catchers were “lavish in their praise of Heving’s pitching talents but frankly confess he has harried them no little in the past with a prolonged wind-up that allowed runners to take no end of liberties on the bases.”

Despite the bad moments in 1930, though, by year’s end Joe had appeared in 41 games (just two starts) and finished 22 of them. He had six saves and a 7-5 record. This season and the next were the years when both brothers, Johnnie and Joe, were in the majors at the same time, but they played in different leagues and never really stood a chance of facing each other.

Joe’s 1930 ERA was a mark he improved on somewhat in 1931, driving it down to 4.89, though his W-L record was a disappointing 1-6 and he worked only half as many games and half as many innings. The lengthy windup remained a problem and McGraw just didn’t seem to trust him, and in August McGraw sent him down to Rochester. A note in The Sporting News said, “The big fellow failed to make good and was returned by Manager Southworth. The trouble with Heving was his delivery.” After the 1931 season, the Giants had seen enough and he was released to Indianapolis in the American Association as part of a deal for Len Koenecke.

Joe spent 1932 with Indianapolis, and won 15 games while losing nine. He gave up only 74 runs in 173 innings and struck out 91 batters. The Chicago White Sox took him from Indianapolis in the Rule 5 draft at the end of September. Playing the full year in the American League, Joe had a very good year with an excellent 2.67 ERA (7-5) in 118 innings. He started six games and had three complete games, his best outing being a 4-0 shutout of the Red Sox on August 22.

By contrast, 1934 was a poor year. Though Heving threw 88 innings, he lost his first seven decisions and didn’t win his first game of the year until September. It was in Chicago, in late relief, with the White Sox facing Lefty Gomez. Gomez had entered the game 24-3 and riding a 10-game win streak, but he walked Luke Appling and Jimmy Dykes doubled in the go-ahead run, while Joe held on for his first (and only) win of the year, throwing the final three innings. In late October, he was released outright to Louisville. He was expected to excel for the Colonels, but refused to report. “There wasn’t much hope for Heving joining Louisville,” reported The Sporting News in December. He lost a year, and Louisville traded his contract to Milwaukee for Wayne LeMaster on the condition that he report.

He reported. Heving threw a career-high 256 innings with Milwaukee in the American Association in 1936, winning 19 games and losing 12, with a 3.48 earned run average. In mid-June, The Sporting News termed him “the most effective relief pitcher in the business.” His prime pitch was his sinkerball. The day they clinched the American Association pennant, September 3, 1936, the Brewers sold him to the Cleveland Indians for 1937. It would be his third shot at the major leagues. He made the club with Cleveland in the spring and he was 8-4, used exclusively in relief and working in 40 games with a 4.83 ERA. In 1938, Joe began the year with Cleveland, and was 1-1 while only working six innings (and giving up six earned runs) for the big-league club. By May, he wasn’t looking nearly as good as he had and consequently Cleveland placed him on waivers. He was purchased for $7,500 by Milwaukee and spent most of the season there (8-8, 4.60) until the Brewers sold him to the Boston Red Sox on August 1.

Jack Malaney of the Boston Post wrote in the August 11 Sporting News that “not too much is to be expected” of Heving. Heving made an impression his first month on the job, shutting out the A’s, 5-0, in the second game of an August 17 doubleheader sweep that put a stop to a six-game Red Sox losing streak. It was his first start for the Sox, and he allowed seven hits, and also initiated all three Red Sox double plays in the game. Despite what Malaney reported, Joe had success, starting 11 of the 16 games in which he appeared and finishing the last couple of months of 1938 at 8-1 (3.73). Malaney wrote six months later, in February 1939, “Heving proved a life-saver when he was brought up from Milwaukee last summer. His side-arm sinker-ball pitching proved effective. …[Manager Joe] Cronin found that Heving was more effective as a starter than as a relief man and will continue to work him that way.” Cronin, instead, continued to use him in relief.

As noted above, he led the American League in relief work both in 1939 and 1940, at one point winning seven games in a row in relief for the Red Sox in 1939 (11-3, 3.70). He appeared in 46 games and put his name in the record books with one of the wins. On July 13, the Red Sox played the first night game in team history, in Cleveland. The game went 10 innings and the Red Sox won it, 6-5. The winning pitcher was Joe Heving. He was a holdout in the spring of 1940, the last player signed, but again served primarily as right-handed relief. His first start of the year was on August 15, and he threw a three-hitter. Joe appeared in another 39 games the year he turned 40. Each year he threw over 100 innings, and Peter Golenbock quotes Joe’s teammate Doc Cramer as saying, “Cronin wanted to use him every day, and Joe Heving couldn’t stand it. He was too old for that.”

An Associated Press article hinted that it might have been that Cronin and Heving didn’t get along: “Why Heving was given up by the Red Sox was obscure. On the 1941 Cleveland roster, he joins Jim Bagby, another pitcher who didn’t get along with Boston’s manager, Joe Cronin.” The Red Sox were ready to move on, but Heving’s career was far from over. Boston sold him to Cleveland in early February 1941, and he stuck with the Indians for four seasons. He showed the Red Sox a bit of comeback, shutting them out on six hits on July 27. Ted Williams kept his quest for .400 alive, though, with a 2-for-3 day. Heving posted ERAs of 2.28, 4.89, 2.75, and 1.95, winning 19 games and losing 9 for the Indians over the four years. He missed a little time in mid-1943 after being struck by a car outside the hotel in Cleveland, but still got in 72 innings that year. It was a remarkable year; early on, it was revealed that he was not only one of the older players in baseball at the time; he was already a grandfather! His one and only win of the year came on the final day, an 11-inning win over the Philadelphia Athletics. Grand-fatherhood may not have set well with Joe; he was divorced from his first wife in the fall of 1943. A more likely reason is that he’d met Nancy Pearl Palmer, a beauty queen who sang country music on a radio show in Irvine, Kentucky. Nancy was 23, and the two were married in May 1944. His final season for the Tribe was an excellent one, particularly for a 44-year-old, 8-3 with the aforementioned 1.95 earned run average. He appeared in 63 games, becoming the oldest pitcher to lead the league in appearances.

In 1945, after holding out in the springtime, Heving was released by the Indians on May 21. He was signed by the Boston Braves two days later and finished his career with a few more months in Boston. He appeared in only three games, and threw only five innings, though he wound up with a 1.000 winning percentage (1-0). The Braves gave him his release on August 9, 1945.

At the plate, Joe was a career .170 batter, with 41 hits (the only extra-base hits were eight doubles), and 18 RBIs to his credit. He scored 20 runs.

After baseball, Joe took up a completely different trade, working as an ironworker. He had three children in all. One from his first marriage: Evelyn. With his second wife, Nancy, he had Joe Jr., who was himself a welder and ironworker, and Jolene, a medical technologist; . At various times during his later years, he indicated that he was a steelworker and car loader for Acme Newport Steel and a pipefitter for the Southern Railway. Heving died at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Covington on April 11, 1970.

Last revised: March 12, 2024 (zp)

Sources

Joe Heving’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Thanks to Nancy Heving, Mary Sterling, and Wayne Tucker.

Full Name

Joseph William Heving

Born

September 2, 1900 at Covington, KY (USA)

Died

April 11, 1970 at Covington, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.