John I. Taylor

John I. Taylor is one of the most controversial figures in Boston Red Sox history. After Boston won the first 20th-century World Series in 1903, American League president Ban Johnson faced a dilemma. The Boston championship team was owned and operated by Midwestern interests. Johnson wisely decided that the team should be sold to a local group. Gen. Charles Henry Taylor, publisher of the Boston Globe, bought the team. He immediately made the youngest of his three sons the team president. John I., as he was called, ran the team from 1904 through 1911.

John I. Taylor is one of the most controversial figures in Boston Red Sox history. After Boston won the first 20th-century World Series in 1903, American League president Ban Johnson faced a dilemma. The Boston championship team was owned and operated by Midwestern interests. Johnson wisely decided that the team should be sold to a local group. Gen. Charles Henry Taylor, publisher of the Boston Globe, bought the team. He immediately made the youngest of his three sons the team president. John I., as he was called, ran the team from 1904 through 1911.

Subsequently assessing Taylor’s time as Boston’s president, Red Sox historians were not impressed. Donald Hubbard in The Red Sox Before the Babe unfavorably characterized Taylor as a “spoiled” rich kid, a “screw-up,” and an “incompetent.” Frederick Lieb in The Boston Red Sox called Taylor the “worst enemy” of his own teams. Peter Golenbock in Fenway – An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox asserted that Charles Taylor bought the team only to give the “wild” John I. “something to do.” Glenn Stout in Red Sox Century characterized Taylor’s tenure as “easily the most unsuccessful of any Boston owner.”

Nevertheless, after Boston won the 1904 American League pennant, Taylor’s organization went through the unpleasant but necessary task of overhauling an aging team. After seven acrimonious years during which the team was incrementally disassembled and rebuilt with younger players, the franchise emerged with a highly competitive team that featured arguably the greatest set of outfielders in the history of baseball.

Tris Speaker, Duffy Lewis, and Harry Hooper were all excellent hitters and outstanding defensive outfielders. Hooper and Speaker were subsequently elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. The three outfielders, along with the other young players assembled by the Taylor organization, won the 1912 World Series over the New York Giants. The 1912 team established the best regular season won-lost record in Boston baseball history. The same outfield trio won another world championship in 1915

John Irving Taylor was born on January 14, 1875, in Somerville, Massachusetts, outside Boston. He was the third and youngest son of Charles Henry Taylor and Georgiana Olivia Davis. He had two brothers (William and Charles) and two sisters (Elizabeth and Grace). His father was a Civil War veteran and joined the Boston Globe as a temporary business manager in 1873 at the age of 27. Taylor eventually became the paper’s publisher and ultimately created a profitable, large-circulation newspaper. His descendants were publishers or presidents of the Globe until the paper was sold in 1999.

After graduating from high school, John went to work for the Globe. For several years, he worked in both the Globe’s advertising and editorial departments. Although John had journalism “in his blood,” he discovered that he did not like the newspaper business. Being a good amateur athlete, he found himself increasingly drawn to baseball. He attended as many games as he could. Taylor’s grandson later remembered, “My granddad was an absolute nut about baseball.”

In 1903, Boston beat Pittsburg in the World Series, the first ever held. With the new American League’s foothold in Boston secure, Ban Johnson sought local buyers. Two bidders quickly emerged. Boston Mayor John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald headed one group. Charles Taylor led the second.

Eager to strongly sustain the team’s success in Boston, Johnson accepted the Taylor bid. Taylor’s ownership of the Globe was probably the deciding factor. The Globe would assure strong, sustained media coverage of the team’s activities. Within that framework, Johnson’s American League would receive plenty of ink. The selling price was reported to be about $145,000.

Charles Taylor immediately turned over the operation of the team to his son. John I. had been advertising manager of the Globe but left the position a few months before the April transaction, [Boston Globe, April 19, 1904] and was no longer employed at the Globe when the family purchased the club in his name. Charles’s decision to entrust his new acquisition to the now unemployed John I. drew guffaws from the sports press, which saw the move as a thinly veiled attempt by a busy father to keep his playboy son out of trouble.

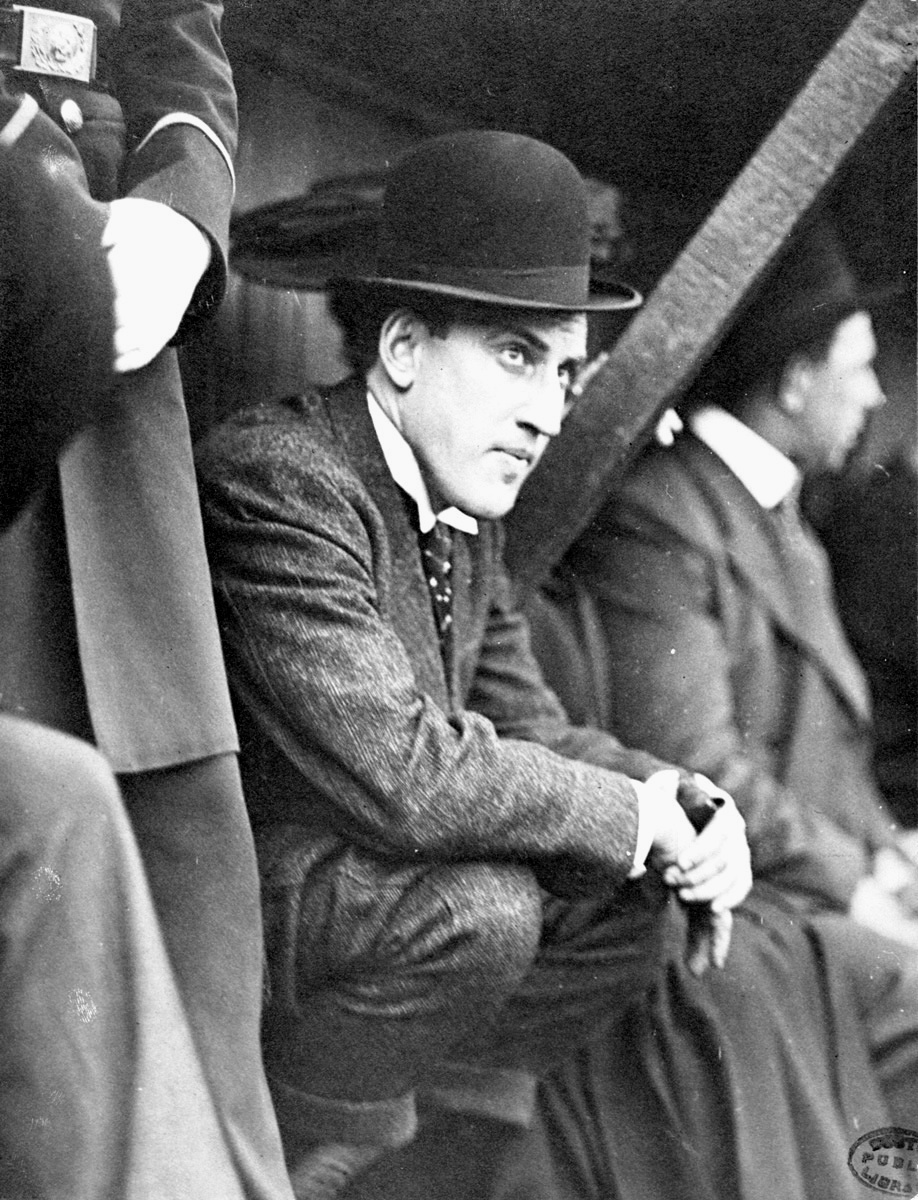

At 29, John I. became the Boston team president. The Globe subsequently described him as a “man of fine physique, tall and well-built, with large, piercing eyes.” While thoroughly enjoying social occasions that included good drinks and lively women, Taylor was also both analytical and outspoken. He had great admiration for those who knew and measured up to their jobs. He also detested bluff and bluffers and had little time for what he called “bunk.” Like most people, John I. was better fitted to ride with winning teams than to deal with the bumps of losing. Sportswriter Lieb noted that when the team lost, Taylor became a hot-tempered, sarcastic taskmaster to many of his players and managers.

Upon the announcement of the ownership change, Lieb wrote, John I. gave manager Jimmy Collins a strong public endorsement. “I have the utmost confidence in Jim Collins,” he announced, “and consider him as good a manager as there is in the country and shall co-operate with him so far as it lies within my power to give Boston as good a ball (team) as it has had in the past, and will spare neither money nor effort in that direction.”

The 1904 Boston team went on to win a thrilling pennant race, which went down to the final series of the season. According to author Donald Hubbard, one disastrous trade nearly cost Boston the pennant.

On June 17, 1904, the club sent hard-hitting and highly popular outfielder Patsy Dougherty to the New York Highlanders for utilityman Bob Unglaub. It was easily one of the most one-sided trades in Boston baseball history. Boston baseball fans were irate and blamed Taylor and his new organization. Taylor became a laughingstock in Boston and within professional baseball. Only the subsequent Boston pennant saved Taylor from a groundswell in Boston calling for his immediate removal. League president Ban Johnson may have had a hand in orchestrating the trade, the better to make the New York team more competitive, thus creating more of a draw and stronger ticket sales.

After Boston won the 1904 pennant, beating New York on the final day of the season, Taylor immediately issued a public challenge to the New York Giants to play a world championship series. (The World Series was not yet a fixed, permanent event.) Giants owner John T. Brush, who hated Ban Johnson and did not want to further elevate the American League to equal standing with the National League, refused, even though each team’s players were looking forward to an additional postseason paycheck.

In 1905, Boston compiled a 78-74 record and dropped to fourth place, 16 games behind the pennant-winning Philadelphia Athletics. The team’s pitching suffered a significant decline; the staff earned-run average was 2.84, fifth in the league. Except for Jesse Tannehill (22-9), no starting pitcher finished with a record above .500. The team simply didn’t score many runs; Cy Young had a 1.82 ERA and was 18-19. In 1904, the staff had had a 2.12 ERA with three 20-game winners.

The effects of increasing age combined with complacency were beginning weaken the team. The players who jumped from the National League to help establish both the Boston franchise and the American League were getting into their late 30s.

After the season, without consulting Jimmy Collins, Taylor sent new contracts to the players calling for a general cut in salaries. The players began grumbling immediately. In January 1906, Sporting Life reported that a syndicate that included Collins made an offer to Taylor to buy the team for $125,000.

According to Peter Golenbock, the working relationship between Collins and Taylor began to deteriorate rapidly. Collins began publicly attacking Taylor. Both men desperately wanted to win. They strongly disagreed on how to make that happen. Essentially, both wanted to have the power of a modern-day general manager to run the team. Ban Johnson backed Collins. Charles Taylor backed his son.

Hubbard writes that Collins considered many of his 1905 players his friends. Many won two pennants and a championship with him. Collins unwisely trusted them to do the right thing. As a result, he gave his team a lot of leeway in 1905 spring training and remained loyal to the group even as they faded from contention. At the start of the 1906 season, Hubbard writes, Charles Taylor dispatched John to Europe to ease the awkward situation.

One positive result emerging from his time in Europe was his marriage to Cornelia R. Van Ness, from a distinguished San Francisco family. Cornelia provided a much-needed stability to Taylor’s social activities. They subsequently had four children. One of the streets bordering Fenway Park eventually was named Van Ness Street.

Fred Lieb called Boston’s 1906 season “the great debacle” and a “season-long nightmare for Boston fans.” The 1903-04 champions “plunged through the cellar door into a bottomless pit.” The team finished in last place with a miserable 49-105 record, the worst in major-league baseball that season. The Boston Beaneaters of the National League were 49-102, which contributed to the “nightmare” of ’06. As a team, the Americans’ hitting and pitching both dropped significantly. Boston scored only 463 runs in 155 games, compared to 579 runs in 153 games in 1905. The 1906 pitching staff compiled a 3.42 ERA, worst in the majors.

One of the most symbolic events of this horrible season was the team’s 20-game losing streak, which set a major league record at the time. The streak started on May 1 and ended on May 25, when Tannehill hurled a shutout. While attendance dropped initially, the fans returned to see when the Americans would end the string of losses.

The Taylor vs. Collins struggle for team control continued. In the clubhouse, particularly after a losing game, Taylor would sarcastically berate each player he thought should have performed better. Collins then strongly discouraged Taylor from going into the clubhouse. John I. countered by setting up a chair in the passageway leading to the clubhouse and verbally blasting each passing player who he believed needed it.

With a bad knee, Collins began not playing regularly any more; he played in only 37 games in 1906. At the end of June, citing nerve problems, Collins began not wearing his uniform on the bench. Again citing nerve issues, he subsequently made outfielder Chick Stahl the temporary manager and took off to a nearby beach. He did not inform John I. of his beach trip and Taylor suspended him. In late August, Collins was again suspended, this time by Ban Johnson. Stahl took over as acting manager for the rest of the season.

The 1907 Reach Guide summarized Boston’s woeful 1906 effort: “The poor tail enders of 1906 presented the most melancholy spectacle ever witnessed in major league ball. The cause of this awful slump was the decadence of the team’s veterans, which had set in the year before.” However, a hint of a brighter future emerged with Taylor’s signing of catcher Bill Carrigan out of Holy Cross College. In 1907, Taylor had a hectic season, as the club had four managers and one acting manager. In order of appearance they were Chick Stahl, Cy Young, George Huff, Bob Unglaub, and Jim McGuire.

The manager shuffle began after Chick Stahl committed suicide during spring training. It was a particularly tragic event. He had served as the club’s acting manager at the end of 1906 and was well-liked in the Boston clubhouse. He swallowed carbolic acid after writing a suicide note. Boston scheduled a special exhibition game with the nearby Providence Grays as a tribute to Chick and to raise funds for his widow. Taylor canceled another potentially lucrative exhibition game scheduled to be played on that day. Each of the other major-league teams contributed $50 and the Cleveland players contributed $165. Taylor topped the other contributions by giving $500.

After Stahl’s death, Cy Young took over as interim manager. Despite strong urging by Taylor to become the full-time manager, Young declined. Taylor then entered into negotiations with Hugh Duffy of the Grays, a former Boston idol, to manage the club. These fell apart over the length of the contract.

A frustrated Taylor turned to George Huff, who was director of athletics at the University of Illinois. Huff lasted only eight games, posting a 2-6 record. By May 1, finding the contentious Boston situation too much, Huff resigned and returned to his position at Illinois. Taylor, however, appreciated Huff’s ability as an evaluator of baseball talent, and he hired Huff as a scout. It turned out to be a good move by Taylor. While Huff’s stint as a manager was an embarrassment, he made an enormous contribution to the franchise by scouting and signing Tris Speaker.

To succeed Huff as manager, Taylor selected first baseman Bob Unglaub. Although his short tenure (9-20) has been generally dismissed, one key development happened while he was in charge. Taylor traded the 38-year-old Jimmy Collins to Philadelphia. Collins’s erratic behavior in 1906 had lost him a great deal of public support in Boston. He was now a “poison” in the Boston clubhouse.

Taylor’s choice for his fourth manager in 1907 was Fred “Deacon” McGuire. One day after Boston hired McGuire, Taylor traded another of the remaining members of the 1903-04 champions, pitcher Bill Dinneen, to St. Louis’s American League club, the Browns. In return, Boston got $1,000 and Beany Jacobson, who, after pitching two innings, never pitched major-league baseball again. Boston finished 1907 with a 59-90 record in seventh place. The Americans ended 32½ games behind the first-place Detroit Tigers.

Although 1907 was another dismal season for Taylor, he did arrange for the first-ever night baseball game to be played at the Huntington Avenue Grounds. It was an exhibition game between a Cherokee Indian team and the local semipro Dorchesters. The Indians brought their own lights and placed them around the field. Their collective light was estimated at more than 50,000 candlepower.

In December 1907, , Taylor announced that he was going to change the name of the Boston team from the Americans to the Red Sox for the coming year. Boston’s National League team had dropped their characteristic red stockings after the 1907 season, and Taylor quickly adopted them for his team. Part of his rationale was to take advantage of a Boston tradition: The city’s first professional baseball team (1876) had been the Red Stockings.

The newly renamed Red Sox compiled a 1908 record of 75-79 and finished in fifth place. Boston’s old-to-new transition continued. The Red Sox sold or traded three 1903-04 holdovers, Hobe Ferris (to the Highlanders), Freddy Parent (to the Chicago White Sox), and Bob Unglaub (to Washington). Taylor paid off and released manager McGuire. He subsequently chose Fred Lake, a longtime manager in the New England League, as the new Red Sox manager. The Globe’s announcement of Lake’s selection mentioned that Lake and Taylor were planning a “sliding salary scale for each position.” Apparently the plan was never implemented, although the concept did reflect Taylor’s predisposition toward a pay-for-performance salary structure.

According to Fred Lieb, Taylor was investing in his team, “spending money right and left.” Taylor’s intensive scouting effort began to pay dividends. Tris Speaker, Smoky Joe Wood, and Harry Hooper were all signed by Boston in 1908. Harry Lord replaced Collins at third base. At midseason, Taylor traded for Garland (Jake) Stahl who played a solid first base for the remainder of the season. As a former player-manager for Washington, Stahl provided a much-needed stabilizing influence in the clubhouse.

Although the 1908 Red Sox experienced significant transition, two of the biggest moves were made in the 1908-09 offseason. On December 11, Taylor traded Boston’s longtime catcher and Cy Young favorite Lou Criger to the St. Louis Browns for $5,000 and catcher Tubby Spencer.

Although illness and injuries had significantly cut into Criger’s playing time, Red Sox fans were still surprised to see him go. An upset Cy Young lavishly praised Criger’s catching ability, saying, “He was one of the greatest catchers that ever donned a mask. … So confident am I of his judgment that I never shake my head.”

If the fans were surprised to see Criger being packed off, they were bewildered when Taylor traded Cy Young to Cleveland in February 1909. Taylor had repeatedly said that Young would spend the rest of his career in Boston. According to Lieb, some fans thought Taylor had lost his mind, while others thought he was drunk when he made the trade. As for Young, he was publicly very gracious about Taylor’s decision. He expressed his thanks to Boston fans and also thanked Taylor for trading him back to Cleveland, where he had started his big-league career. The Sporting News took a more positive view of the Young trade. It lauded Taylor for his “exceptional wisdom” in making his decision. The trade ultimately yielded little for the Red Sox (Charley Chech, Jack Ryan, and $12,500).

With the departure of longtime favorites Criger and Young, Boston fans started 1909 with low expectations. They were pleasantly surprised when their team posted an 88-63 record and finished in third place. As the season progressed, Boston’s young, athletic players began making a larger impact. Tris Speaker, Harry Lord, and Harry Hooper all had good seasons. Perhaps Taylor had a bit more baseball acumen than the fans credited him with.

The Boston scouts signed two more college players from Vermont who would be future stars for the Red Sox: left-handed pitcher Ray Collins and infielder Larry Gardner, a key figure in three Red Sox world championships.

Once again, there was a managerial change in November 1909. When Lake discussed salary with Taylor, he named a figure and Taylor disagreed. The two men could not resolve their differences. As a result, Taylor released Lake and signed Patsy Donovan, a major-league outfielder for 17 years, as the new Red Sox manager.

According to Lieb, John I. Taylor later confessed: “I believe my 1910 season was my biggest disappointment.” After surging in 1909, the Red Sox fell back a bit in 1910. They compiled an 81-72 record and finished fourth. The big story of 1910 was the Philadelphia Athletics, who simply pitched their way to the pennant. Their staff posted an outstanding 1.79 ERA for the regular season and subsequently won the 1910 World Series.

The 1910 season also marked the debut of the Lewis-Speaker-Hooper outfield combination. Lieb wrote, “Many fans and critics rank this outfield as the greatest of all time. Other outfields may have had more slugging power (Meusel, Combs, Ruth) but the Red Sox trio had better defensive skills.” One baseball writer characterized the trio as covering the field “like a carpet.”

Taylor enjoyed personally scouting on the West Coast, and Duffy Lewis was one of his discoveries. Taylor liked Lewis, a fancy dresser who became known as “John I.’s boy.” Lewis later recalled, “John I. was a good boss. Maybe he was sharp at times, but he always bought the boys suits of clothes whenever they had big days.”

After the season, Taylor also resolved a festering Boston team issue: Harry Lord, the team’s third baseman. Several newspaper articles reported that Lord wanted Patsy Donovan’s job. Lord was Boston’s captain but was benched in August 1910. Taylor made infielder Heinie Wagner the new team captain. When Lord angrily demanded to be traded, Taylor quickly sent him to the Chicago White Sox. The Taylor-Lord problem reportedly originated over the funding of a postseason Red Sox exhibition game played in October 1909 against a team of Maine all-stars. Lord, who arranged the game, claimed he lost money on the game. When Lord wanted to play another exhibition game in Portland in 1910, Taylor refused. Lord emerged with a label of being “money crazy.”

After the trade, Lord challenged the Red Sox to an exhibition game against a team of traded Red Sox assembled by him. The winners would get $2,000. Lord said, “(We) just wanted to show Boston that it has traded off a better team than it has now.” Once again, Taylor refused.

Because of Taylor’s fondness for the West Coast, he decided to have the team hold spring training at Redondo Beach, California, near Los Angeles, in 1911. A large number of players were brought into camp, enough to furnish two touring teams, and after a full schedule of games along the California coast, they broke into two teams and played games as they traveled east, in Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Texas, Nebraska, and Missouri – 63 games in all.

As the 1911 season started, the Taylor family decided to leave the Huntington Avenue Grounds, which had been leased since the franchise began in 1901. The Taylors decided to use land they owned and build a ballpark to be called Fenway Park.

The Fenway Park project was probably a part of a bigger deal in which two key Taylor family objectives could be accomplished: By selling a share of the team after the new park was under way, the family would recoup a huge financial reward from its original investment; and John I. Taylor could shed the headaches of operating the team while still being associated with it.

The deal was also very attractive to the American League hierarchy. American League president Ban Johnson tolerated John I. Taylor, but it is debatable if he ever recognized Taylor as a true “baseball man.” Perhaps Johnson was simply tired of regularly being called to Boston to settle issues he thought should be handled by club ownership. A group chosen by Johnson would operate the new club. John I. Taylor would become a Red Sox vice president and his father would sit on the board of directors.

As soon as the new stadium construction started, the Taylors sold half of their interest in the Red Sox for $150,000. The sale price recouped their original investment. They needed the money to complete the construction of Fenway Park. When finished, the stadium reportedly cost $350,000. A key part of the deal was that the family would remain the owners of Fenway Park and the land on which it was built, the park serving as a magnet to help develop the value of their adjoining real estate holdings. The subsequent team owners would rent the park for $30,000 a year. The Taylors rented Fenway for eight seasons (1912-1919). On January 4, 1912, Jimmy McAleer was named president of the Boston Red Sox. He and Robert McRoy had become owners of a 50% share of the ballclub in a sale on September 14, 1911. It was later revealed that Ban Johnson was involved as well, behind the scenes.

The last Red Sox game at the Huntington Avenue Grounds was a win over Washington. Taylor bade goodbye to the ballpark by allowing free access to all Boston boys under 12 years old to attend the game. A Boston Globe picture captures thousands of youthful fans enthusiastically watching their hometown heroes. It was good publicity for the newspaper as well. After the game, the sod was removed and taken to the new facility.

Fenway Park opened on April 20, 1912, to general acclaim, and the official “Dedication Day” took place on May 17. The Red Sox went on to win the 1912 pennant, compiling a 105-47 record. They won the World Series over the New York Giants. Every player on the 1912 Red Sox roster had either been signed by or acquired via trade by John I. Taylor and his organization. The Globe later estimated that over the span of Taylor ownership (1904-1911), John I. had acquired more than 110 players in his efforts to improve the team. In his obituary, in 1938, the Globe concluded, “While he was in the game, there was no closer student of the game than John I. Taylor. It was mainly on his own judgment of players themselves that he finally brought to Boston so many ‘naturals’ who came flying up to the big league grade.”

In 1914, Joseph Lannin became principal owner of the Red Sox, after paying the Taylor family a reported $300,000 for their remaining common stock interest in the Red Sox. However, Gen. Charles Taylor retained “quite an interest” in the preferred stock of the club. He also was a trustee in Fenway Realty Trust, which financed Fenway Park.

Upon completion of the sale of the Red Sox to Lannin in 1914, Ban Johnson, who clashed repeatedly with John I. Taylor over the years, publicly praised him. “John I. Taylor was president of the club for eight years and his work in building up was one of the greatest value and paved the way for the great success of 1912,” Johnson said.

In October 1916, immediately after the team won its third world championship in five years, Lannin cashed in and sold his common stock Red Sox holdings to Harry Frazee and a partner for a reported $675,000. As Red Sox owner, Frazee also bought Fenway Park in May l920 from the Taylor family. Part of the money was provided by a $300,000 mortgage held by the New York Yankees as part of the package Frazee arranged when he sold Babe Ruth to the New York owners.

As for Charles I. Taylor, he enjoyed an active life during retirement. Peter Golenbock quoted his grandson William as remembering Charles I. as a “favorite with the next generation of Taylors because he would always take them to Fenway Park.” He remained a close follower of the Red Sox, but his interests focused primarily on his family. He also liked tennis, golf, and polo. Extensive gardening occupied much of his time and he spent long hours caring for the flower beds and rock gardens at his home in Dedham, outside Boston. He died on January 26, 1938, at Massachusetts General Hospital after a brief illness. He was 63 years old.

In its obituary, the Boston Globe noted two innovations that Taylor had helped introduce, Ladies Day and the press box, writing: “He was one of the first magnates in the country to assign a day on which women were admitted free to the baseball park. He was the first president to assign private quarters away from the paying spectators for the baseball writers.”

In a separate article, Globe columnist Melville Webb Jr. wrote, “It always has been a compliment to be considered ‘a good baseball man.’ John I. Taylor was that.”

Sources

Timothy Gay. Tris Speaker, The Rough and Tumble Life of a Baseball Legend (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2005)

Peter Golenbock. Fenway: An Unexpurgated History of the Boston Red Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s and Sons, 1992)

Donald Hubbard. The Red Sox Before the Babe (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009)

Frederick G. Lieb. The Boston Red Sox (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1947)

James Morgan. Charles H. Taylor, Builder of the Boston Globe (Boston: Boston Globe, 1923)

Bill Nowlin. Day by Day With the Boston Red Sox (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2006)

Bill Nowlin. Red Sox Threads – Odds & Ends from Red Sox History (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008)

Bill Nowlin, ed. When Boston Still Had the Babe, The 1918 World Champion Red Sox(Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008)

Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson. Red Sox Century, The Definitive History of Baseball’s Most Storied Franchise (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005)

John Thorn, Pete Palmer, and Michael Gershman. Total Baseball Seventh Edition (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001)

Paul J. Zingg. Harry Hooper, An American Baseball Life (Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1995)

John I. Taylor obituary, The Sporting News, Necrology, February 3, 1938

“Death Takes John I. Taylor,” Boston Globe, January 27, 1938

Boston Globe, Sporting Life, The Sporting News, Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, New York Times

National Baseball Hall of Fame – John I. Taylor File

The Baseball Index, SABR, accessed November 20, 2009

Wikipedia.org, Charles H. Taylor, accessed December 9, 2009

Baseball Reference.com

Full Name

Born

January 14, 1875 at Somerville, MA (US)

Died

January 26, 1938 at Boston, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.