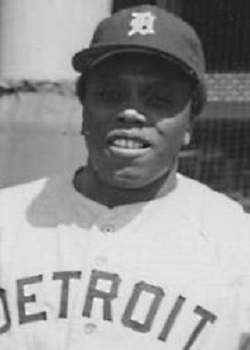

John Young

John Young carried an impressive 6-foot-3, 210-pound frame during his baseball playing days. Even more impressive than his physical stature on the field, however, was the stature he later gained as a baseball ambassador for the underprivileged. In founding the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities program, Young left an indelible mark on the game that transcended his very brief big-league career.

John Young carried an impressive 6-foot-3, 210-pound frame during his baseball playing days. Even more impressive than his physical stature on the field, however, was the stature he later gained as a baseball ambassador for the underprivileged. In founding the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities program, Young left an indelible mark on the game that transcended his very brief big-league career.

John Thomas Young was born of African descent on February 9, 1949, in Los Angeles, California to parents Louis and Thelma Young. He was an only child. And growing up in South Central Los Angeles, Young was a self-described “brat in need of a good role model.” Fortunately, he found that role model in Edward Hamm, a local youth whose interest was in sports — rather than more nefarious pursuits. In reflecting on his formative years, Young noted, “And I just thought so many times that if Edward Hamm were to have been into drugs or gangbanging, I kind of think I would have led that way.”1

Instead of heading down the wrong path, Young attended Ascension Catholic School before advancing to Mount Carmel High School, another parochial school, where he found success as student body vice president, a varsity track participant, and an All-California Scholastic Federation basketball player.2 Young displayed enough basketball talent that he was offered scholarships by the University of Utah and Washington State University, both of which he declined. He also played baseball, despite the fact that he “grew up on pavement and played in parks where grass grew by accident.”3

During the 1950s and 1960s, inner-city Los Angeles was a baseball hotbed with a wealth of talent. “This is approximately 10 years after Jackie Robinson and for African Americans, baseball was the sport,” Young reflected.4 “There were thousands of leagues. You’d play on two or three teams.”5 In fact, on Young’s Compton-based Connie Mack League baseball team alone, the roster included notable future major-league talent Enos Cabell, George Hendrick, Lenny Randle, and Wayne Simpson.6 Other noted contemporaries (and future big-leaguers) Willie Crawford, Bobby Tolan, and Bob Watson also learned the game in the lots and fields of the area. But the “best games around,” according to Young, were when his team played the Murray family, whose team included future Hall of Famer Eddie Murray.7

It was Young’s skills on display at Mount Carmel, however, that drew the attention of big-league scouts. On June 6, 1967, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds in the 27th round of baseball’s June Amateur Draft. Young rejected their contract offer (including a $10,000 bonus), however, because “he thought he would be worth more after college.”8 In reflecting on his youthful confidence, Young admitted, “Ya know, I was a spoiled brat athlete. My greatest ambition in high was to get me a brand new car. In fact, a deuce and a quarter. A Buick 225. And signing [for] my bonus.”9 In hopes of improving his future draft status, he opted to play baseball at Chapman College, located in nearby Orange, California.

Young, nicknamed “Duke,” got off to a slow start at Chapman during his freshman year. The early-season struggles were blamed on development delays caused by his earlier participation on Chapman’s varsity basketball squad. Coach Paul Deese admitted, “At the beginning of the year, we wouldn’t let left fielder John Young throw the ball before the game. It would have given his weak arm away.”10 As the season progressed, however, Young greatly improved all aspects of his game. His speed and penchant for swiping bags were particularly impressive. “Second base is a challenge to me,” Young explained. “I’d like to steal third, too, but coach won’t let us.”11

Finishing the regular season hitting .299 with three home runs, 29 runs scored and 21 stolen bases, he was recognized with all-conference honors. In the NCAA College Division postseason, Young was named the Pacific Coast Regional Tournament MVP, and his exceptional play was recognized as one of the major factors that led the Panthers to the national championship in 1968. During the summer months that followed — in addition to working as a bank mailroom clerk — he continued his strong play for the Springfield Caps of the Central Illinois Collegiate League. There he was selected as an All-Star outfielder, and hit a league-leading .350 while swiping 29 bags.12 Young also received the honor of being named a first alternate on the U.S. Olympic baseball team, which played exhibitions during the 1968 Games in Mexico City.13

Although Young excelled athletically at Chapman, he struggled academically; thus, his eligibility to remain with the team on scholarship was in question heading into his sophomore season. As such, Young enrolled at Fullerton Junior College in the fall of 1968 in an attempt to raise his grades.14 The question marks surrounding Young’s sophomore season were answered, however, when on February 1, 1969, the Detroit Tigers drafted him in the first round (16th pick) of the big leagues’ January Amateur Draft (secondary phase). Scouted by Jack Deutsch, Young signed a contract including a $30,000 bonus.15 Although this ended his college baseball career after only one season, he nonetheless left a lasting impression on the Chapman baseball program.

In reflecting on Young, Chapman coach Deese said, “If Young had stayed with us longer, we would have had turnaway crowds at every one of our games. He would have done more for college baseball than anyone I know. He was the most sensational player I ever saw. He was as big as Willie McCovey and had the speed and potential greatness of Willie Mays.”16 Young’s Chapman team captain Bob Zamora added, “They talk about how Mickey Mantle got down the line from the left side. John Young was right there with him.”17 In 1991, Young was inducted into the Chapman Athletics Hall of Fame.

Assigned by Detroit to the Lakeland Tigers of the Class-A Florida State League for the 1969 season, Young had to adjust to his new life as a professional baseball player — and the ugly effects of segregation. He remembered, “Jim Leyland was my first manager in Lakeland in 1969. This was the Deep South, and [segregation] kept me from getting an apartment, so I didn’t have a place to live until he let me live with him.” Leyland made a lasting impression on Young. “Jim was like Crash Davis [from the movie Bull Durham]. He was an old-school player who was a great influence on the younger kids,” Young later noted.18 Leyland positioned Young at first base, which became his primary position for the rest of his career. He started strong out of the gate — tripling in the season opener to help spark Lakeland to a 3-1 victory over the Winter Haven Red Sox — and continued to excel throughout his first season in professional ball, despite missing a month due to a late-season foot injury that limited him to 99 games.19 Although he hit only four home runs, Young ended the season with a league-leading .325 batting average, finished eighth in RBIs (60), and leveraged his speed to top 10 finishes in triples (11) and stolen bases (26). This resulted in his being named the league’s MVP.20 To continue his development, the parent club assigned the promising 20-year-old to their affiliate in the rookie-level Florida Instructional League North to finish the year.

In 1970, Young was promoted to the Montgomery Rebels of the Double-A Southern League, where he spent the entire season. Playing against more formidable competition, he suffered a sophomore slump. In 128 games, Young hit .251 with nine home runs, 50 RBIs, and 10 stolen bases. Still, although it was recognized that he was “a year or two away,” he was touted as a possible “first baseman of the future” for the Tigers.21

Back with Montgomery for the 1971 season, Young rebounded, with his offensive numbers drastically improving across the board. Early on, he gained prominence for “running wild” on the basepaths, stealing 15 consecutive bases without being caught to begin the season.22 By midseason, Ed Katalinas, the Tigers’ director of player procurement, reportedly had identified Young as a promising candidate to eventually become a “successful big-leaguer.”23 At season’s end, he had finished in the league’s top 10 in several offensive categories. All told, in 122 games, Young hit a robust .297, clubbed 17 home runs, drove in 63 runs, and swiped 30 bags for the Rebels. His strong performance was rewarded with a call-up to the major leagues during September roster expansions.

On September 9, 1971, with the Tigers down 12-6 to the Boston Red Sox, Young made his major-league debut as a pinch-hitter for shortstop Ed Brinkman to lead off the bottom of the ninth inning. Facing pitcher Jim Lonborg while being so nervous that his “knees were shaking,” he anxiously swung at the first pitch and unceremoniously grounded out to third base. Following the game, teammate Gates Brown used humor to cheer up the dejected Young, wisecracking, “Son, don’t feel bad. It’s not your fault. You had no business being up there, anyway!”24

On September 9, 1971, with the Tigers down 12-6 to the Boston Red Sox, Young made his major-league debut as a pinch-hitter for shortstop Ed Brinkman to lead off the bottom of the ninth inning. Facing pitcher Jim Lonborg while being so nervous that his “knees were shaking,” he anxiously swung at the first pitch and unceremoniously grounded out to third base. Following the game, teammate Gates Brown used humor to cheer up the dejected Young, wisecracking, “Son, don’t feel bad. It’s not your fault. You had no business being up there, anyway!”24

With the Tigers in the midst of a pennant race, the rookie did not see action again until after the team was mathematically eliminated from playoff contention. On September 25, with the Tigers leading the New York Yankees 7-5, he entered the game in the top of the fourth inning as a defensive replacement at first base for Al Kaline. In his first at-bat of the game in the bottom of the fifth inning, Young hit an opposite-field double for his first big-league hit, and scored later in the inning for his first big-league run. After grounding out in his next at-bat, Young singled to center in the bottom of the eighth inning to collect his first big-league RBI. Following the 10-7 Detroit victory, Young quipped, “I’ll always remember my first major-league hit, even though it was a wrong-way-field double.”25 He never appeared in another major-league game; thus, with two hits in four at-bats, Young finished his big-league career as a .500 hitter.

Young’s big-league trajectory was derailed by a serious wrist injury requiring surgery that he suffered during 1972 spring training. “I could do everything but turn over a bat or twist a key,” he later said.26 Assigned to the Toledo Mud Hens of the Triple-A International League for the 1972-1973 seasons, the effects of the injury limited Young to 30 and 88 games, respectively. And although he was able to battle his way to a total of 106 games in 1974 — initially with the Evansville Triplets of the Triple-A American Association before being sent back to Montgomery — his overall performance was middling. In December 1974, the Tigers — dealing with a logjam of potential first basemen — cut ties with Young after six seasons in their organization, trading him to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Ike Brookens.

In reflecting on his time in the Tigers organization, Young admitted, “There was a lot of frustration. My mindset was to get 60 miles north to Detroit, but they had a championship team in 1968 and no one broke into that starting lineup until it fell apart in ‘74.”27 Still, going forward he always maintained a soft spot for the Tigers, helping to organize alumni reunions for his old club.28

Young was assigned by St. Louis to the Arkansas Travelers of the Double-A Texas League. Now a seasoned veteran with six professional seasons under his belt, Young began on his path of helping others by mentoring the younger players. He explained, “I eventually got traded to the Cardinals, and I used the lessons I learned from Jim Leyland there. I tried to be a mentor to the young players they had in their system — guys like Garry Templeton and Ken Oberkfell, and Tommy Herr.”29 Although Young himself rebounded by hitting well over .300 in each of the next two seasons in Arkansas (and was named to the Texas League All-Star team in 1975), he struggled offensively in his third season with the club — even after honing his skills during the prior winter months playing for Tomateros de Culiacán of the Mexican Pacific League.

Still toiling in the minor leagues at age 28 — and with burgeoning star Keith Hernandez locking down the first base position with the parent Cardinals — Young realized his dreams of having a long career as a big-leaguer were unlikely to come to fruition.30 As such, he announced his intention to retire from baseball at the end of the 1977 season. Going out in style, in his final game, Young led the Travelers to the Texas League championship with a three-run homer in a 4-0 victory over the El Paso Diablos.31 After grounding out in his final at-bat of that game, the Arkansas fans gave Young a standing ovation in a show of appreciation for his efforts during his tenure with the club.32 Following his retirement, he briefly resurrected his career as a player in 1978, playing in 12 games for the Mexico City Diablos Rojos of the Triple-A Mexican League.

Once he hung up his spikes for good, Young completed his education, receiving his bachelor’s degree in secondary education from Auburn University at Montgomery, after having taken classes during his offseasons at Fullerton College, Bowling Green State University, and Alabama State University.33 He also stayed close to the game he loved. Young quickly went to work as an associate “bird dog” scout for the Chicago Cubs under the tutelage of Negro Leagues legend John “Buck” O’Neil before rejoining the Detroit Tigers organization in late 1978 — this time as a minor-league batting instructor.34

Shortly thereafter, the Tigers reassigned him to a scouting position, before naming him the organization’s scouting director in 1981. In doing so, Young became the first African-American scouting director in Major League Baseball history.35 “I’m thrilled to death,” he said of the historic assignment.36 From 1984 to 1994, Young worked in scouting capacities for the San Diego Padres, Texas Rangers, and Florida Marlins before returning to the Cubs to serve as a special assistant to the general manager from 1994 to 1996. As a scout, all told Young signed 21 players to their first professional contracts, with three becoming major-league All-Stars (Howard Johnson, Robb Nen, and Glenn Wilson).37 In 2014, he was recognized with the Legends in Scouting Award by the Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation, an organization for which he was a long-time board member.38

Exposed once again to amateur baseball during his time as a scout, Young was surprised to see firsthand the extent of the decline in participation of African Americans in the game since the 1950s and 1960s. “Pretty soon I saw that everything had changed. Inner-city baseball programs were very disorganized, there was little talent, and the best athletes were in football, basketball, and track,” he noted.39 “The gangs had taken over the parks. Kids in this city [South Central Los Angeles] weren’t getting a chance to play. The schools that used to turn out such great talent weren’t generating much of anything.”40 And perhaps more bluntly, Young once commented, “Nowadays, kids think baseball is a white man’s game.”41 Inspired by lessons from famed fellow scouts Phil Pote and Bob Zuk, he and other scouting colleagues (including Steve Flores, Damon Oppenheimer, Mike Sgobba, Dale Sutherland, and Ron Vaughn) hatched the idea of a program to create a baseball development system for inner-city youths.42

Young pitched the proposal to influential Baltimore Orioles general manager Roland Hemond. Hemond recalled, “I thought John had a great idea.” Realizing Young needed considerable support for his undertaking, Hemond involved Commissioner Peter Ueberroth. “Peter was impressed that I was passionate about what a great idea John had and how such a program could grow, so he called [Los Angeles] mayor Tom Bradley, who he had worked so closely with putting on the [1984] Olympics, and [he] got some seed money from Mayor Bradley as well as Major League Baseball,” Hemond explained.43 With this assistance — plus support from contemporary baseball star power including Hubie Brooks, Eric Davis, Tony Gwynn, and Darryl Strawberry — Young founded the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) program in 1989.

What began as a modest South Central Los Angeles campaign with 11 youths attending the first tryouts has since exploded into 200 international cities with 260,000 annual participants as of 2017. Numerous alumni of the RBI program have gone on to the major leagues, including prominent players Carl Crawford, Coco Crisp, Yovani Gallardo, James Loney, Manny Machado, CC Sabathia and Justin Upton. As baseball is at its core, RBI’s stated mission largely centers on the game itself, including aspirations of increasing the involvement of minorities and the underserved in the game, and preparing participants for the collegiate or professional level. In expounding upon the program, however, Young explained, “The objective of RBI is not to get minorities to the big leagues. The objective is to get more kids to use the lessons they learn in baseball to succeed in life. I didn’t want baseball to become so expensive that it becomes a sport played by the elite only. But RBI isn’t only about playing baseball: We have a life skills program, and we work with a lot of kids in a lot of areas. The goal of the RBI program is to develop big-league citizens, and that’s what I’m most proud of.”44

Although Major League Baseball assumed administrative control of RBI in 1991, Young “tirelessly stomped” for the program over the years, maintaining no other title than that of founder. “I’m the founder. And as the founder, you can never get fired,” he quipped.45 Having settled near his hometown of Los Angeles in nearby Irvine, California, in the later years of his life, Young had been in failing health as a long-time sufferer of type-2 diabetes, and a dialysis patient since 2009. Consistent with his desire to help others, however, Young became a frequent speaker to dialysis patients on the benefits of maintaining a positive outlook.46

Shortly after having a leg amputated due to complications of the disease, Young passed away in Los Angeles on May 8, 2016, at age 67. He was survived by his wife Sheryl — the “love of his life” whom he met during his playing days in Montgomery — and children Dorian, Jon, and Tori.47 Young was laid to rest in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. In a show of respect upon his passing for the significant contributions he made to baseball and the African-American community, tributes flooded in from numerous prominent media outlets, as well as from dignitaries ranging from MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred to civil rights activist Jesse Jackson. The City of Los Angeles also recognized their native son, permanently naming the intersection at West 90th Street and South Hoover Street as “John Thomas Young Square.”48

Despite being a promising prospect, Young played in only two career big-league games. He had no bitterness, however, preferring to maintain a bigger-picture view. “I look back on it now and I would’ve loved to have spent more time in the big leagues,” Young said nearly 30 years after his retirement as a player. “But if I had played 10 more years, RBI never would have happened. No doubt about that. So I have no regrets. Not one.”49

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Young’s file at the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York; Ancestry.com; Baseball-Reference.com; Newspapers.com; and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Frank Stoltze, “Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities Founder John Young Reflects on RBI Program,” Southern California Public Radio, April 4, 2011, http://www.scpr.org/news/2011/04/04/25587/rbi-founder-john-young-reflects-his-program/, accessed December 22, 2016.

2 John Young, “John Thomas Young: Mt. Carmel High School Graduate 1967,” Mount Carmel High School Alumni Foundation, http://mtcarmelcrusaders.org/profiles/67bio_jyoung.htm, accessed January 7, 2017; City of Los Angeles, Resolution, “John Young RBI,” January 4, 2011.

3 Mark Whicker, “Whicker: John Young Was Devoted to Revitalizing Baseball in Urban Areas,” Orange County Register, May 10, 2016.

4 “Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities Founder John Young Reflects on RBI Program.”

5 Gary Klein, “Program Brings Baseball Back to Inner City,” Los Angeles Times, May 22, 1990.

6 John Wagner, “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office,” Toledo Blade, April 20, 2008.

7 Ibid; Gordon Edes, “Scout Sees Inner Cities’ Hope Wasted,” Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), May 31, 1992.

8 Al Carr, “Theft a Game to Chapman Ace,” Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1968.

9 “Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities Founder John Young Reflects on RBI Program.”

10 Al Carr, “Chapman Nine Starts to Jell at Playoff Time,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1968.

11 “Theft a Game to Chapman Ace.”

12 “John Young,” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/in/john-young-75874954, accessed January 9, 2017; “Four Bobcats Selected for CICL All-Star Team,” The Pantagraph (Bloomington-Normal, Illinois), August 23, 1968; “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

13 “John Young RBI.”

14 “USC, Chapman Slate ‘Playoff’ Next Spring,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1968.

15 “Chapman Star Signs With Tigers,” Los Angeles Times, February 14, 1969; Watson Spoelstra, “Stanley Glances in Two-Way Wonder,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1969.

16 Al Carr, “Deese Looks North to Alaska for Better Baseball Opportunity,” Los Angeles Times, December 17, 1970.

17 “Whicker: John Young Was Devoted to Revitalizing Baseball in Urban Areas.”

18 “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

19 Associated Press, “Lakeland Nabs FSL Opener,” Palm Beach Post, April 18, 1969.

20 “O-Twins’ Warner Manager of the Year,” Orlando Sentinel, August 27, 1969.

21 Jim Hawkins, “Tigers Finally Going After Latin American Players,” Detroit Free Press, November 1, 1970.

22 “Dixie Association: Young Running Wild,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1971.

23 Associated Press, “Future Looks Good Down on Tiger Baseball Farms,” The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), July 3, 1971.

24 Howard Kellman, 61 Humorous & Inspiring Lessons I Learned from Baseball (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2010), 26.

25 Associated Press, “Tiger Rookie Stars,” Battle Creek (Michigan) Enquirer, September 26, 1971.

26 “Scout Sees Inner Cities’ Hope Wasted.”

27 “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

28 Tony Paul, “Former Tiger Young, Who Started RBI Program, Dies,” The Detroit News, May 9, 2016.

29 “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

30 Bruce Markusen, “Former Tiger John Young Has Left a Legacy With Inner-City Baseball Program,” Detroit Athletic Company blob, November 8, 2013, https://www.detroitathletic.com/blog/2013/11/08/former-tiger-john-young-has-left-a-legacy-with-inner-city-baseball-program/, accessed January 20, 2017; Barry M. Bloom, “Young Scores Big With RBI Program,” MLB.com, February 9, 2006, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/1308934/, accessed January 20, 2017.

31 Harry Readel, “Edelien Breaks Diab Dreams With His Breaking Pitches,” El Paso Herald-Post, September 10, 1977.

32 “Young’s Yarns,” The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Sep 19, 1977.

33 “John Thomas Young: Mt. Carmel High School Graduate 1967.”

34 “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

35 Daniel E. Slotnik, “John Young, Promoter of Baseball for the Underprivileged, Dies at 67,” The New York Times, May 11, 2016.

36 Detroit Tigers News Release, October 13, 1981.

37 Major League Baseball Office of the Commissioner News Release, May 9, 2016; “John Thomas Young: Mt. Carmel High School Graduate 1967.”

38 Ken Gurnick, “Selig Helps Hand Out Awards at Scouts Fundraiser,” MLB.com, January 19, 2014, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/66850462/commissioner-selig-helps-hand-out-awards-at-scouts-foundation-fundraiser/, accessed January 23, 2017.

39 Michael Hirsley, “Reviving Game in Inner Cities,” Chicago Tribune, July 18, 2004.

40 Tim Wendel, High Heat: The Secret History of the Fastball and the Improbable Search for the Fastest Pitcher of All Time (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2010), 96.

41 “Scout Sees Inner Cities’ Hope Wasted.”

42 Bill Plaschke, “Scout’s Honor: It’s Phil Pote,” Los Angeles Times, August 09, 2009; Jim Sandoval and Bill Nowlin, Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2011), 142.

43 Ben Platt, “MLB’s RBI Program Enters 20th Year,” MLB.com, February 25, 2008, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/2387908//, accessed January 22, 2017.

44 “Baseball Diamond is Mentor’s Office.”

45 “Young Scores Big With RBI Program.”

46 Miss Alaina Fruge, “Tiger’s Manager, Jim Leyland Salutes Kidney Patient and Former Tiger John Young,” 1200 AM WCHB, https://wchbnewsdetroit.newsone.com/2776299/tigers-manager-jim-leyland-salutes-kidney-patient-and-former-tiger-john-young-today/, accessed January 22, 2017.

47 “South LA Community Commemorates John T. “Duke” Young,” John Thomas Young Square Street Co-Naming Ceremony Program, July 6, 2016.

48 City of Los Angeles, Motion, May 31, 2016.

49 “Young Scores Big With RBI Program.”

Full Name

John Thomas Young

Born

February 9, 1949 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

May 8, 2016 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.