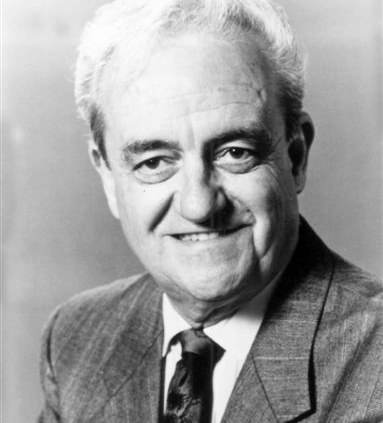

Roland Hemond

Like the sea captains of an earlier era, Roland Hemond was a native New Englander who has sailed far and wide and worked in many ports along the way. A kid with a fervor for baseball, he started at the bottom sweeping out the stadium at Hartford’s Bulkeley Stadium, home of the Hartford Chiefs, only to rise through the ranks and become general manager of two major-league teams, the White Sox and the Orioles. He was an executive for seven teams and three times was named Major League Executive of the Year — by The Sporting News in 1972 with the White Sox and in 1989 with Baltimore and by United Press International in 1983 for his work with the White Sox. Through the years, Hemond groomed such executives as Dave Dombrowski, Walt Jocketty, Dan Evans, and Doug Melvin. He helped create the Arizona Fall League and played a significant role in Team USA’s preparation for the Pan American Games and the 2000 Olympics.

Like the sea captains of an earlier era, Roland Hemond was a native New Englander who has sailed far and wide and worked in many ports along the way. A kid with a fervor for baseball, he started at the bottom sweeping out the stadium at Hartford’s Bulkeley Stadium, home of the Hartford Chiefs, only to rise through the ranks and become general manager of two major-league teams, the White Sox and the Orioles. He was an executive for seven teams and three times was named Major League Executive of the Year — by The Sporting News in 1972 with the White Sox and in 1989 with Baltimore and by United Press International in 1983 for his work with the White Sox. Through the years, Hemond groomed such executives as Dave Dombrowski, Walt Jocketty, Dan Evans, and Doug Melvin. He helped create the Arizona Fall League and played a significant role in Team USA’s preparation for the Pan American Games and the 2000 Olympics.

In the summer of 2001, Roland was recognized by the Society for American Baseball Research for his contributions to scouting, as SABR instituted the annual Roland Hemond Award. Roland himself was its first recipient.

In December 2001, he was crowned “King of Baseball” by Minor League Baseball at their 2001 annual Winter Meetings banquet. Each year the minor leagues salute a baseball veteran for his years of service. Baseball America gave him their “Distinguished Service Award” on its twentieth anniversary, recognizing 12 people who had 20 or more years of service in the game.

In January 2002, Roland Hemond was the recipient of the Boston Baseball Writers Association’s most prestigious award, the Judge Emil E. Fuchs Award for “long and meritorious contributions to baseball.”

In the early years of the twenty-first century, Roland still manifested the same passion for the game today. While working with the White Sox as a special advisor to GM Ken Williams, he was able to devote time and energy to helping arrange care for baseball people in need, to honoring others who have served and to concern himself with promoting baseball to young people. He was also active, inspiring baseball research through SABR. In 2005, Hemond saw the White Sox win their first world championship since 1917, earning himself a commemorative ring.

Hemond served as an executive advisor for the White Sox through 2007 and then returned to Phoenix where he became special assistant to the president of the Diamondbacks. In February 2011, the National Baseball Hall of Fame named him the second recipient of the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award — second only to O’Neil himself, who was awarded it posthumously in 2008. On being told of the award, Hemond was almost tongue-tied, calling it, “the epitome of the highest of pinnacles that I feel I would ever enjoy.” He had no idea the award was coming. “I couldn’t handle it. I couldn’t talk,” he admitted. [Associated Press dispatch, February 23, 2011]

In January 2017, the Arizona chapter of SABR was renamed to become the Hemond-Delhi Arizona Chapter.

Roland Hemond was born on October 26, 1929 in Central Falls, Rhode Island, a textile mill community next door to Pawtucket. His father Ernest was born and raised in Rhode Island; his mother Antoinette moved to the area from a suburb of Montreal. “We were French Canadian. Actually, I didn’t speak English until I was about 6 years old. It was a typical French community in the city — those three- and four-story tenement houses built close to the textile mill. People couldn’t afford cars when they first arrived so they would walk to work and they built houses close to the textile mills.

“My father was a bread salesman. He delivered bread to stores for Bamby Bread, for 32 years. My mother was a seamstress. In the home. My sister married but she didn’t work after she was married. She helped take care of my parents and my brother while I’ve been on a baseball circuit. My brother at birth had a problem. He never could hear well. He lived a tough life. My mother was a saint. He lived at home until he was about 22 years old and then he tried different places. He ended up very happy in one of those combined type homes where they have four or five people who are afflicted and they have constant 24-hour care. Once my mother saw that he was happy and well taken care of, that’s when she started slipping. Her efforts and dedication, she was a saint on wheels. A dedicated lady.

“I can still speak French and occasionally do when I get calls from newspaper people in Montreal. Matter of fact, I announced a trade in French one day at the baseball convention. I asked John McHale, the president of the Montreal Expos at the time. Murray Cook was the general manager. I asked, ‘Hey, how about if I announce it in French and we’ll shock all the baseball people.’ People got a big kick out of it. That’s probably the first time in major league baseball history that a deal at the baseball convention was announced in French. I wish I could speak Spanish. I advise all young people in the game to learn to speak Spanish. French helped me earlier in my career with some of the young French players, like Claude Raymond and Georges Maranda and Ronald Piche. They all made it to the major leagues. They were young pitchers attending their first spring training in the Milwaukee Braves organization in Waycross, Georgia, and they couldn’t speak English. They were thrilled when I greeted them, just like some of the Latin players appreciate it when some of the baseball people speak Spanish to them when they hit the country.”

Roland’s interest on baseball began early:

“I first fell in love with baseball about 1938. I was going on eight years old at the time and just fell in love with the Red Sox. I started playing on the corner playgrounds. Jimmie Foxx was my first hero; he had that MVP year in ’38. When I went to my first game at Fenway and I saw that green grass, I was hooked. Then Ted Williams came on and Bobby Doerr. I was just a diehard Red Sox fan like so many other New Englanders. I devoured the newspapers. The Providence Journal and the Pawtucket Times. As I was growing up, you’d stand on the street corner waiting for the Daily Record to be flipped out at the corner hangout.

“My family members weren’t necessarily interested, but they didn’t discourage me from going to ball games. Leo Laboissiere was a fine athlete in Central Falls, about three or four years older than me. He asked my mother if it was okay to take me to Fenway. Then he had to back out. Something came up. So I took the bus myself. At that time, I was around 10 years old. I took the bus from Pawtucket to Boston, then the subway to Fenway, and saw a doubleheader there that day, and then came back. My mother said, ‘Oh, how did you enjoy the games?’ I said, ‘Oh, they were great, Mom!’ She said, ‘How did Leo enjoy it? Did he have fun too?’ I said, ‘I’ve got to confess. He didn’t come with me.’ She was startled. My mother would not have allowed me to go on my own. I had never been on a subway or anything, but I found my way. I found my way to Fenway.

“That first game was a doubleheader that I still so vividly remember. It had to be 1939 or ’40, one or the other. The Red Sox were playing the White Sox and there was a 6:30 curfew at the time. There was a rain delay during the first game and then the rain stopped and they got into the second game. The Red Sox were desperately trying to beat the curfew. Jimmy Dykes was the manager of the White Sox. Joe Cronin — he was up in age at the time — tried to steal home and he was thrown out at the plate. Jimmy Dykes brought in, I think it was Edgar Smith, in relief. Then he said, no, this was not the pitcher that he wanted, and the umpire said, ‘Well, he’s pitching!’ He [Dykes] was wasting time, trying to buy time. Lou Finney got a base hit to win the game, just before, like 6:29 p.m., with a 6:30 curfew. I was just elated!

“Dykes got fined for it by the league, and the next day when Dykes’ club went to Washington, there was the same umpiring crew. In the pre-game meeting at home plate, Dykes gave them a lineup card listing only eight players, without a pitcher. The umpires asked, ‘Who’s pitching?’ Dykes said, ‘Heck, you told me who was pitching yesterday, so you might as well name him!’ And they threw him out of the game!

“I was a Braves fan also, but not as fanatical.”

Roland followed minor-league ball as well:

“I spent a lot of time at Pawtucket, at McCoy Stadium. I was there when it opened in 1942. Bump Hadley pitched that day. He was out of the major leagues by then, and he was the starting pitcher for, I think it was, the Lynn team pitching against Pawtucket. The Pawtucket Slaters.

“I got up to Fenway about two or three times a year. I used to get there before the gates opened, because I was always hoping that Ted would be taking some extra hitting. My mother let me play hooky twice, with her blessing. Once, to see Bob Feller pitch. I think that was 1940 or ’41. I said to my mother, ‘Mom, this is one of the great pitchers of all time.’ And she said, ‘Well, I guess it’s OK.’ I think he won 2-1.

“And the 1946 World Series also. I saw the fourth game. St. Louis won 12-3. I sat in the centerfield bleachers. I was there at like six o’clock in the morning. I went with some friends and sat in that little triangle in the center-field bleachers. The ’46 Series…there was sort of an auditorium celebration day at school or something and I couldn’t sing worth a darn. The Sacred Heart brother told me, ‘Just lip the words, don’t sing. You’re throwing off the group.’ So I said to my mother, ‘Why go? They don’t even want me to sing.’ She let me go to the World Series game. I just stood in line at the bleachers that time and got tickets that morning.”

Roland played neighborhood, Legion, and high school baseball as a youngster, and even matched up in one decisive series of American Legion games against another future general manager, Lou Gorman.

While serving a four-year stint in the Coast Guard, Hemond was stationed at Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field, but caught as many Red Sox games as he could when they visited Yankee Stadium. He retains an excellent and detailed memory of many games he saw over a half century ago, and can almost provide play-by-play for key games like the final deciding games of the 1949 pennant race. Modestly, he simply offers, “It shows the impact that the game has upon you at a young age, and that the memories remain so vivid.”

How did he move from being a fan to working in baseball? How did he get his start? It was actually a deliberate decision on his part. He wanted to work in baseball. Hemond took leave during spring training to visit a cousin, Ray Lague, who was a right-hand pitcher in the Pittsburgh Pirates farm system who was going to train in Deland, Florida. He introduced himself to Sox GM Joe Cronin, but there was no work for him there, so he took a bus and hitch-hiked to the Pirates training camp. While waiting to see Branch Rickey, a chance meeting with the wife of former ballplayer Leo McMahon, who had blinded in combat in World War I, led to an introduction to Fresco Thompson, farm director of the Dodgers. Thompson referred him to Charlie Blossfield, GM of the Hartford, Connecticut farm club of the Boston Braves.

“Mr. Blossfield said the Hartford Chiefs were going to honor Bob Quinn, the father of John Quinn, who became the general manager of the Braves. Bob Quinn had been a professional player and then associated with the St. Louis Browns, the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Red Sox, and the Braves in executive positions, presidents of the team and I think part-owner a little bit, too. He was the first curator of the Hall of Fame. He had given Charlie Blossfield his first job, at Zanesville, Ohio. He was to be honored a week or two later and Connie Mack was going to be there. Charlie told me to come back because the Braves officials would be there and he needed their permission to hire me. So I came back for that and met the Braves officials. Joe Cairnes was the business manager of the Boston Braves and in charge of the business operations of their minor league teams.

“They hired me. Charlie Blossfield asked me when I could get out of the service and I said, ‘July the 3rd’ because I’d saved some more leave. I got my first start working there [at Bulkeley Stadium in Hartford] for $28 a week.”

These were modest beginnings, starting at the ground floor, but Roland today stresses the importance of getting to know baseball at all levels:

“I used to unlock the ballpark in the morning and help Harvey Stone, the trainer, to sweep out the park, clean it up and get the concession stands ready. Sell tickets in the afternoon and do some p.a. announcing sometimes. Then I would check in the ticket takers and the concessions people at the end of the night, and then lock up the park at 11, 11:30 at night.

“That still happens with young people in the minor leagues. You wear all sorts of hats, but you’re getting your start. At the end of the season, Charlie said he couldn’t afford me but he wanted me back the next year. About two weeks after I got home in Rhode Island, before I was going to leave for that course at Florida Southern, he called me and he said, ‘There’s an opening in the Braves farm system office, and I’ve recommended you.’ I had learned to type in the Coast Guard, so I went up to Boston and John Mullen, who’d become the farm director because Harry Jenkins was leaving; he’d married a lady from Australia and he had been the farm and scouting director. John was going to need some help in the office so he said he’d give me a two-week tryout, and here I am today. That’s how it all evolved: being lucky to be at the right places at the right time.

“When I first started, I was like an intern. $35 a week. I got a raise. I got to the big leagues and I got a $7 a week raise.”

Roland was working for the Boston Braves, in Boston. Life took another turn, though, as life sometimes does — not only for the Braves with their departure for Milwaukee but for Roland personally as well.

“1952 was my first full year. I joined them late in September ’51. In ’51 I was at Hartford, then didn’t go to Boston until the last week of the season. Then ’52 the full year. At that time I was too young [to travel in the farm system] and they just kept me in the office. I was typing up scouting reports and stuff like that. I got to see a lot of games that year.

“Then I married into the Quinn family. My wife Margo was John Quinn’s daughter, and she’s ten years younger than me. When the team transferred to Milwaukee, I got to know her better then. When I first met her, she used to come into the office sometimes. I was only about 21 or 22. She was only about 11. She was a real brat. I’d step out of the office and she’d sneak in and change the names on the board. We’d have all the farm system players’ names. She’d promote some, demote some. And I’d say to John Mullen the next morning, ‘That little brat Margo Quinn must have been in here.’ She demoted about 10 players and promoted some. She’d mess up the whole board, to see if I could catch it. It was easy to detect, but she’d get a big kick out of it. I’d tell her father, ‘Your daughter Margo, she’s a little pest.’

“I went with the Braves to Milwaukee. That first spring, instead of going to the minor league training camp, John Quinn asked me to help out with tickets, because we moved something like March 18, something like that, and the season was going to open April 7 or 8. Lou Perini had asked the commissioner if they could have an emergency meeting in Florida (to approve the team’s move), and it just happened overnight.

“I was in Milwaukee a day or two after the announcement. They put me on a train and when I got off the next morning, I was in Milwaukee.

“I got married in 1958. I used to tell her I had to wait for her to get out of school. We didn’t date until around ’57, basically. John left after the ’58 season. So we got married November the 8th, and I used to kid, I said, ‘Well, that wasn’t too smart a move. I married the boss’s daughter and he quit six weeks later.’ He went to the Phillies.

“I was eight full years in Milwaukee. Eight full seasons. That was a great experience. I officially became assistant to John Mullen — instead of being an apprentice or an intern — when he became official farm director in ’53. I became the assistant to him for the remaining years in Milwaukee.

“Then I went to the Angels as farm and scouting director, when they became an expansion club. I reported to them January the 3rd, 1961.”

“We have five children. Susan did a lot of associate director’s TV work with the San Diego Padres and ESPN and the West Coast teams, and Anaheim, etc. Bob is now part-owner of the Sacramento franchise in the Pacific Coast League, the River Cats. Jay worked in the farm office of the Florida Marlins for a couple of years, and this past year managed a team in Winchester, Tennessee, in an All American Association. He worked for the Frederick Keys in the Carolina League for a while.

“Margo’s brothers have been in baseball. Bob was general manager with the Cincinnati Reds. A short time with the Yankees before he went to the Reds. Then San Francisco. Brother Jack, he was a minor-league general manager at Davenport, San Jose, Midland and also Hawaii and Portland and Vancouver. It’s a long lineage. Bob Quinn was a player in the 1800s. Then John Quinn, and then the sons and our family and now we’re into another century. I think we’re the first family to be in three centuries.”

[When you started with California, what was your position with them?]

“I was farm director and scouting director. Fred Haney hired me as farm director and scouting director. I was there for 10 years with them and then became general manager of the White Sox on September 14, 1970. The whole ’60s with the Angels, and then from the last two weeks of the 1970 season through 1985 I was general manager of the White Sox.”

“We [the White Sox] were never endowed with much money to work with. The White Sox team that I joined, that year they were 56 and 106. Chuck Tanner was our manager and we had worked together with the Angels, and we’d been in the Braves’ organization together. We worked extremely well together. At the first Winter Meetings in December of 1970, we moved 16 players in the first 18 hours of the convention. Coming and going. We improved by 23 games the first year. Then that next winter, we acquired Dick Allen and Stan Bunsen in a couple of big deals and we made a heck of a run at it in ’72. We weren’t eliminated until the last week. In ’73, it looked like we were ready to make a good shot at it and we opened the season about six games in front. At the last part of May, Ken Henderson, whom we had acquired that winter to play center field, tore up his knee badly at a play at the plate. Dick Allen also suffered an injury. That robbed us of an opportunity. I think we would have had a shot at it that year.

“In ’74 and ’75 the rumors were heavy that the club might move or be sold, so we couldn’t make very many moves. Then Bill Veeck came about and in ’77 we gave it a real good run again. We came back after a dismal ’76 season and made a good run that year against Kansas City. [Working with Bill] was a tremendous experience that I greatly treasure and will forever relish. It was a fantastic experience to be with him. In all facets of life. Baseball as well. He was just an incredible man. He used to say, ‘Don’t bother preparing a budget, Roland. We don’t have any money. We’ll think of something.’ We had a lot of fun and competed as best we could.”

When Veeck came in as the new owner, GM Hemond was ready to pull the trigger on one trade during the winter meetings, but he held up out of respect for the departing owner, John Allyn. He was prepared to send Jim Kaat to the Phillies, but Kaat was owner Allyn’s favorite White Sox. Roland told Veeck, who suggested he go ahead and finalize the deal but not announce it until 45 minutes later, when the ownership change had been itself made official at the convention.

As a brand-new owner, Veeck told Hemond to “let your imagination run rampant.” The Boston Globe’s Gordon Edes describes the duo’s first bold move. “Hemond took one look at the lobby of the Diplomat [Hotel in Hollywood, Florida], which resembled a rotunda furnished with high-back chairs and four tables, and decided it was the perfect place to set up shop. No whispering behind a potted palm for the White Sox. Hemond went up to Veeck’s room as he was coming out of the tub, having taken off his artificial leg to soak the limb. ‘What if we grab a table,’ Hemond says,‘and put up a sign that says, “Open for Business?”’

“‘What are you waiting for?’ Veeck said. ‘Do it.’ Hemond commandeered a table, slipped a $20 bill to an assistant manager, and got his sign. While rival GMs gaped, Veeck instructed the team’s PR man, Buck Peden, to call every half-hour. ‘Bill would answer as if another GM was on the line and say, “Hey, Buzzie, how you doing?” to make other clubs think we were doing business.’

And, of course, they were. Hemond recalled how at 10:15 that Friday night Veeck turned to him and said, ‘We’re going to make four deals by midnight.’ And they did.”

Roland says, “Then in ’77, he [Veeck] came up with the idea ‘let’s rent players for a year’ because free agency had come about and he knew he couldn’t compete. So we traded young players like Bucky Dent, Rich Gossage, and Terry Forster to get Richie Zisk and Oscar Gamble. Signed Eric Soderholm as a free agent, and he was the Comeback Player of the Year. Zisk hit 30 home runs and Gamble hit 31. Soderholm hit 25. That was quite a fun year. It was hard for Bill, again, to compete on a financial basis, but I would never trade those five years for anything. Then Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn bought the club and we made some moves, signing Carlton Fisk as a free agent, and acquired Greg Luzinski. The club got better and better and we won the division by 20 games in ’83. We lost a tough post-season series against Baltimore.”

As his stint with the White Sox as general manager ended, Roland had another opportunity to experience another whole realm of baseball.

“I went to the commissioner’s office for a year and a half. In about May of ’86, Peter Ueberroth asked Jerry Reinsdorf — I’d been retained by the White Sox in a capacity as a special assistant. Peter asked permission, if they could have me in the front office, the commissioner’s office, because of my experience with ball clubs. I was there for a year and a half until the opportunity came to be general manager of the Baltimore Orioles. Edward Bennett Williams, the owner of the Orioles, I was interviewed by him and club president Larry Lucchino. He was impressed that I had been at Bulkeley Stadium in Hartford also, because as a young boy he had sold hot dogs and beer at Bulkeley Stadium. He was from Hartford. He said the hot dogs were cold and the beer was warm.

“I spent eight years with the Orioles, and then five years with the Diamondbacks and now back with the White Sox. I don’t regret it [not being with the Diamondbacks as they won the 2001 World Series]. I’m happy for them. I thoroughly enjoyed their accomplishment, and you know that during the period of time you were there you made some contributions that led to their success. I was thrilled to be asked by the White Sox to come back. The young general manager Ken Williams asked Jerry Reinsdorf if he could ask permission from the Diamondbacks for me to join him.”

[When you joined the Diamondbacks, was that just as they were forming up? Did you come in at the ground level, one of the first hires?]

“Yes, as soon as Jerry Colangelo found my not being retained by the Orioles, then he contacted me and I joined the Diamondbacks and we all worked for the preparation for a couple of years for the expansion draft and then the next three years with them. We won 100 games our second year. I think people have a tendency to forget about that. They think about [2001], but we went to the post-season with 100 victories our second season. Played the Mets in the playoffs.

I became executive vice president of baseball operations, basically the same type job that I now have with the White Sox. [As an expansion team] there was no farm system, and I was in that position also when I joined the California Angels way back, which was the Los Angeles Angels, when I started a farm system and scouting department right from scratch. With the Diamondbacks, we didn’t play for two years in the major leagues, so when we started, we started a rookie club in Arizona and South Bend in a Class-A league. We had to hire minor-league managers and coaches, instructors, and scouts and all that stuff. And players.”

[Why had you moved from the Angels?]

“What happened, Fred Haney wanted to remain as general manager, but the Angels were talking about him retiring. Walter O’Malley had talked to the Angels’ people and recommended Dick Walsh, who had been in the Dodger organization, and they hired him on a long-term contract as the general manager. A year later, then, I went to Chicago and became general manager. The White Sox asked permission and it was my first opportunity as a general manager.

“I had 15 years with them. It was a long time, under three different ownerships, and in ’85 we kind of slipped a little bit. They decided to make a change, but I still had two more years on my contract, so they gave me another title. About May of that next year, Peter Ueberroth asked Jerry Reinsdorf if they could sort of loan me to the commissioner’s office, and I decided, hey, that would be an interesting project.

“Dr. Bobby Brown was the President of the American League. One of his duties was the grassroots baseball. Summer leagues and the various programs. Babe Ruth program. American Legion. I helped him and I traveled around. Cape Cod League. The Northeastern League they had in New York State at that time. A new league in Ohio. The Great Lakes League. The Jayhawk League. I’d come back with reports on each of the franchises and what I thought could be improved and what we should do to help them.

“In May of ’86, that’s when I joined the commissioner’s office as special assistant to the commissioner. It was in April 1987 when Al Campanis appeared on the TV show Nightline and made disparaging remarks regarding the capabilities of minorities. We all felt sorry for Al…this was unfortunate. Al had helped and had given support to minorities throughout his baseball career. He had played shortstop in Montreal alongside Jackie Robinson, his teammate with the Montreal Royals when Jackie went from the Negro Leagues to the Brooklyn Dodgers farm system.

“He could be classified as a hero now. It really sparked efforts to institute a program to help minorities to gain baseball employment other than within the playing ranks. Commissioner Ueberroth had spoken at length, and emphatically, that baseball should hire more minorities in various non-playing positions. I had listened closely to his appeal. I went through the Baseball Encyclopedia, while watching a game on TV — nobody had told me to do this — I was pulling out names of all the minorities who I knew that had played at least one game in the big leagues. Latinos and blacks. I compiled a list of 926 names. The next day after Ted Koppel’s Nightline interview with Campanis, Peter called me in the office and I told him I had a list of 926 people. ‘You do? How do we find these people? How do we know if they’re interested in baseball?’ I think in the past many of the minorities didn’t even let you know they’d be interested, because they figured they didn’t have a chance. Those were the facts of life. They hadn’t seen any action. Peter then hired Clifford Alexander and Grant Hill’s mother, Janet Hill. They had an agency in Washington, D.C., where they were helping minorities get placed in the corporate world. He also hired Harry Edwards, the sociology professor at the University of California in Berkeley and former Olympic track star. Then he had me meet with them, and we prepared questionnaires to send out to as many people as we could find out where they might be located, so they could indicate what they might like to do if they had an opportunity to get back into the game.

“Alexander and Hill concentrated mainly on front office positions and minor league jobs. Edwards was more for coaches and managers, jobs of that nature. I was sort of the coordinator working with them. As this was growing quite rapidly, I started operating out of the Scouting Bureau’s office in El Toro, California, so that I could more readily meet periodically with Harry Edwards. They gave me one of the offices there. That was an interesting project.

“The commissioner also sent me to Australia. He assigned me to Japan with the major-league all-star team to represent the commissioner’s office. People should spend some time in the commissioner’s office. There’s a tendency to say, ‘Well, what do they do up there?’ Well, they do a lot of things. That’s why there’s more marketing now. There’s more TV. They work on a lot of programs to help our game. You have greater respect when you’re not working just with your own ballclub. It helped me to broaden my scope of imagination. Not too long after, I got the job with Baltimore.

“Hank Peters preceded me in Baltimore. He had a fine career there, but they’d had a couple of bad years just before I arrived. I got hired about November the 3rd or 4th of ’87. They’d had a bad year in ’87 and then when I joined them in November [as vice president and general manager], it wasn’t a good club. We lost the first 21 games in 1988. I used to tell myself, ‘Well, I didn’t create it. I inherited it.’ That’s why you get those jobs. Then the next year, we improved by 32 1/2 games. And our payroll was only $8.5 million, the whole payroll. Williams had been the owner for some time. He had the ’83 club. He bought the Orioles about 1978, ’79 I think. In ’83 I was with the White Sox and they beat us in the playoffs. Then they kind of slipped from then on and started going the other way. When I came in, the manager was Cal Ripken, Sr. We made a change early in the ’88 season, after six games. Frank Robinson, we made him the manager, and we lost our next 15. We made some trades that summer. Mike Boddicker to the Red Sox for Curt Schilling and Brady Anderson. Traded Fred Lynn in late August for Chris Hoiles. We traded Eddie Murray that winter, after the season, at the Winter Meetings, to the Dodgers for Juan Bell, Brian Holton, and the pitcher Ken Howell. We traded him immediately to Philadelphia for Phil Bradley. The next year we really improved by an enormous number of games. It was one of the biggest comebacks of all time.”

It was in fact a 32 1/2 game turnaround — from last place and 34 1/2 games out in 1988 to finishing just two games behind the Blue Jays in 1989. Roland was accorded Executive of the Year honors again by The Sporting News. He served eight years in Baltimore.

“Your job should change about every five to 10 years. A new part of the country. Work with different people, different ownership. I was in Chicago through three different ownerships, five years apiece. Each one has a different style. You have to be flexible. You still keep your own basic approaches and beliefs, but with each team or change of ownership, you sort of have to prove yourself again to the new people. It keeps you going. Excited. I started in Hartford, then Boston for two years but then to be with a new franchise in Milwaukee was good. I spent eight full years. That was really exciting. Then 10 years with the Angels on the West Coast. An expansion club. Then to come back to Chicago, it was like having a new job every five years with the different ownerships. The commissioner’s office gives you a different perspective. Then eight years in Baltimore, with three ownerships again. I used to say, ‘I lead the league in owners.’

“It’s amazing. I’ve been in both leagues, been on the East Coast, the Midwest and then the expansion to the West Coast, then back to the East Coast, then the Southwest. It’s been a great experience. I just marvel at the fact even that it happened. You start in the game, fortunate to just get an opportunity, and then to be in your 52nd season….”

[What ever gave you that idea, way back when, to think you could work in baseball?]

“I had such a fondness for the game, such a passion for it, that I said it would be so nice if I could be in the game. I even thought about going to umpiring school. If it hadn’t worked out as it did, I might have gone to umpiring school. I had checked on those possibilities. It was such a lucky stroke that I went to Deland, Florida. If my cousin hadn’t been in the Pittsburgh farm system, and if I didn’t run into Sergeant McMahon and his wife….more likely than not….My plan had been that I would come back to Rhode Island and go to Providence College and go to journalism school, and possibly become a sportswriter. Some way, somehow, I think I would have had a connection with sports, and baseball preferably.”

[Maybe when we get the new owners of the Red Sox in place, they’ll approach the White Sox and say “we need this guy back here…”]

“Well, I’ve wished them well all the time. I remember Mr. Yawkey, the only time I ever met him, it stunned me. Someone said, ‘Mr. Yawkey, this is Roland Hemond, with the California Angels’ and he got up immediately to thank me. And I said, ‘Well, what did I do?’ The Angels beat Detroit that doubleheader that last day of the season [in 1967] and that helped the Red Sox to get in. I think Dick McAuliffe hit into a double play to end it, and it was only the second double play he’d hit into all year. But the Angels had a good series against Detroit. And here Mr. Yawkey, who I sort of idolized as a Red Sox fan because he always used to try hard to put the best possible club on the field, and here he was, he got out of his chair to thank me! I felt real good about that.”

[What is your basic work right now, in terms of executive advisor? Is it sort of a consultant or something?]

“Yes, along those lines, I guess you’d say. I help Ken [Williams, the general manager] and anybody else I can give some advice, through my experience, that might be helpful to the organization.

“Right now, I’m also first vice president of the Association of Professional Ball Players of America. Dick Beverage is the secretary-treasurer of the organization and also a member of SABR. John McHale Sr., who I worked for in Milwaukee in ’59 and ’60, he’s the president. Bob Kennedy, the former general manager and player, is one of the vice presidents along with Dick Wagner, a former general manager. We try to help people in need, in the game, primarily minor league players — presently or in the past — or office personnel. Along the lines that the Baseball Assistance Team does, BAT. But this organization was formed in 1924, primarily by the Pacific Coast League executives and players, and it has branched out to where all minor league players are involved. They pay a little annual dues and the major league players do also, and anybody that we find that needs some help, we try to help them.”

When Baseball America presented Roland their award in December 2001 as one of 12 recipients they wanted to honor on their own 20th anniversary, Roland was flattered. Asked about the award, he found the opportunity to share the attention with a few others.

“It was quite gratifying to me to receive the Distinguished Service Award. Cal Ripken was one of the recipients. John Schuerholz, on behalf of the Atlanta Braves, for the consistency in their organization over the last 10 years. Paul Snyder, I was very, very happy to see him get recognition as their director of scouting. To me, they use the term – and I spoke at the Scout of the Year Foundation dinner, too, the other night — they say the scouts are the unsung heroes. I’ve heard that since I broke in, in the early ’50s, and I have recognized that they’re the unsung heroes, so I always say, ‘Well, let’s sing their praises.’ I want to see them get recognition that they so justly deserve. They never get any headlines. They never get any recognition. A lot of people take the bows, but without their good scouting staff and good scouts and their recommendations and their signings, you’re not successful. Many of us are working towards scouts getting better recognition in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

“Each organization talks that way — we’re going to build a good scouting staff, farm system…and sometimes they do it. After they do and have success, scouts are not mentioned by name enough, so people could have a greater awareness of their contributions. They’ll say, ‘Oh, our scouting staff did a good job.’ Well, mention names of the scouts who have made the organization successful.

“In Boston, you may hear the name of your New England scout but you don’t hear about your Midwest scout. It just bothers the heck out of me. People in the game…I think that’s one of the recognitions I’ve received, in that I pass on credit. It was rather touching for me the other night. Cal received a standing ovation. Schuerholz received a real fine hand, and then as it was building up, I was composed but then when they introduced me, my gosh, it was spontaneous and it was an overwhelming ovation, and then it really hits you. People….they appreciate what you’ve done. It was pretty difficult for me to speak when I got up there. You’d like to mention name after name after name of people who have helped you. No matter what contribution you might have made, you didn’t do it by yourself. Somebody gave you the opportunity to speak at a proper time, then they had to vote on something and pass it. I do consider that my biggest contribution was perhaps helping to get the pension plan for non-uniformed personnel. It was long overdue.

That was in 1983 at a general managers’ meeting. As Mark Derewicz wrote, “Bill Murray, the secretary/treasurer at the commissioner’s office, told Hemond owners weren’t likely to approve the pension package [for non-uniformed personnel]. Hemond was asked to speak. After Reinsdorf and Einhorn granted Hemond permission, he spoke passionately about the importance of scouts and front office personnel. After his speech, the owners unanimously passed the pension plan….”

Hemond explained, “I used to get concerned about seeing people leave the game after many years and then live in poverty and die in poverty. We’d go to spring training and you’d see people retired from all other businesses at spring training but you didn’t see the baseball people who had left the game. They couldn’t afford it. They weren’t there. You’d never see them at the major league games because they didn’t have an automobile. They wouldn’t invite you to their homes because they were embarrassed to show you where they lived. It was pitiful.

“I spoke after the 1983 season, at the owners’ meeting, in front of Bowie Kuhn, the league presidents, owners and general managers. Ted McGrew was an old scout with the Braves and he was in his 80s when I was with him in the ’50s, and he spoke at the baseball convention in 1958 — but he spoke on that matter in front of the mass in a ballroom and pleaded that we needed a pension for non-uniformed personnel. He sat down and it stopped there. Twenty-five years later [I brought it up again.] They made it retroactive to 1981. Bill Murray and Frank Cashen from the commissioner’s office got right with it and implemented it quickly. It didn’t help a lot of the old people who were in the last stages of their lives, but at least it got started. It goes through Major League Baseball; all of the clubs contribute.”

Roland has also been active in the drive to include scouts in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Mr. Hemond ends with a little advice:

“Baseball is entertainment, though for us it’s almost a religion. We have to remind ourselves — we’re providing entertainment, and people can live without it. That’s why you should nurture it and respect it and recognize that we’re not in the medical field or in the food field. We’re not a necessity.

“It has grown to the proportions that it’s attracting more people to get in with other agendas than just the game itself.

“In the ’50s, John Quinn told his son Bob and he told his son Jack and he told me, ‘The three of you should leave the game and go to law school, and come back to baseball. The lawyers will be running this game.’

“There’s a youngster who was in here yesterday [2001 Winter Meetings] who had called me when he was 12 years old in Baltimore and asked, ‘Could I come by and follow you around?”‘ He talked good baseball as a kid, so I had him around for a couple of days, and I stayed in touch with him. He went to Colorado Springs so I recommended him to the Colorado Springs ballclub, to see if he could do anything around the ballpark. They did, and now he’s about 20 years old and he has seven years of baseball experience! He’s getting his degree from Colorado State in business. He’s started looking for a job. I told him, ‘Don’t take a job now. Go to law school. Then you’ll have a better chance to make your mark in the game.’”

“If it were now, I wouldn’t be able to break in. I only had a high school education. I passed up going to Providence College because I had a job in baseball. Some of these youngsters now, they want to start right away in the majors. I tell him, ‘Don’t be over-anxious. You may start with a good job, but fifteen years later you’re still doing that job.’ Breaking in the minor leagues, you’re better off. Then you have to wear more hats. If you wear more hats, then you have a better understanding and respect for what others are doing. Some of them start a little too high and they don’t understand about the grounds crew, how valuable they are. The ticket sellers. The ushers. All the people who make it tick and have direct contact with the fans. Then they can’t administer very well, because some people there know more about what they’re doing. They probably see things that the front office is not doing well. The head ushers years ago probably had better ideas on how to treat the fans.”

Roland Hemond died in Colorado at age 92 of natural causes on December 12, 2021, survived by his wife, Margo; five children, Susan, Tere, Robert, Jay, and Ryan, four grandchildren; and baseball friends and protégés in every organization.

An appreciation of his life can be found at SABR.org/latest/in-memoriam-roland-hemond.

Last revised: December 21, 2021

Sources

This article about Roland Hemond is largely an oral history, based on interviews of Mr. Hemond done by Bill Nowlin over the telephone on November 30, 2001 and December 5, 2001 and in person just following the 2001 Winter Meetings in Boston, on December 14, 2001.

Full Name

Roland Hemond

Born

October 26, 1929 at Central Falls, RI (US)

Died

December 12, 2021 at , CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.