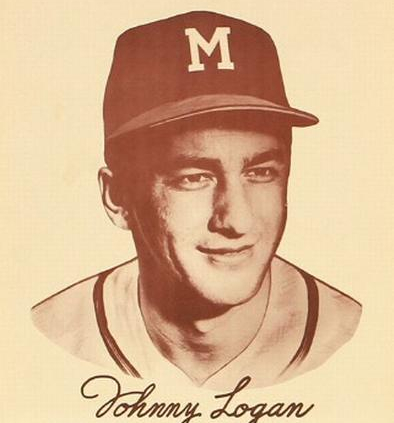

Johnny Logan

The first major-league ballplayer to play on championship teams in both the United States and Japan was John Logan, Jr., known to the baseball world as Johnny. For 14 straight years (1948-1961) he was Milwaukee’s shortstop, the first five with the American Association Brewers, the last nine with the National League Braves. A four-time All-Star, Johnny helped the Braves win back-to-back pennants in 1957 and 1958 and a World Series in 1957.

The first major-league ballplayer to play on championship teams in both the United States and Japan was John Logan, Jr., known to the baseball world as Johnny. For 14 straight years (1948-1961) he was Milwaukee’s shortstop, the first five with the American Association Brewers, the last nine with the National League Braves. A four-time All-Star, Johnny helped the Braves win back-to-back pennants in 1957 and 1958 and a World Series in 1957.

John Logan, Jr. was born in Endicott, New York, on March 23, 1926. (All of the standard references say he was born in 1927, but like many actresses and ballplayers, Johnny fibbed to make himself a bit younger.) He was the youngest of three children, who included brother Michael and sister Mary.

Their father, John Logan, Sr., was a native of Russia. “Stalingrad,” Johnny says. “He was a guard in the empire.”1 The city would have been called Tsaritsyn back then. Johnny’s mother, nėe Helen Senko, was born in Croatia but also lived in the borderland of Poland. Both parents’ families emigrated to America.

“Their families came from Europe and somehow landed in Pennsylvania when they were teenagers,” Johnny said. “When they found out that Pennsylvania was kind of depressed, they packed up and went into Endicott, New York, north of the Pennsylvania line. My parents met in Endicott. They started working for the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company.”2 After marrying and building a small nest egg, John and Helen Logan started their own business.

“They ran a grocery store,” Johnny said, “a neighborhood store. When the people didn’t have the money, they’d come up to Logan to take the credit. When they had the money, they went to the IGA. But that’s where I got to know my neighborhood people. Things were rough then.”3

The family store did offer one benefit to young Johnny: “I was the most popular kid because every day when I went to school, I had bubblegum. Everybody hung around with me because they always knew I had my dad’s free bubblegum. Bubblegum was like a Hershey bar.”4

As a young boy Logan acquired a nickname by which he would be known as long as he lived in Endicott. “I must have been very active,” Johnny said, “and in the Russian language, to settle a young kid, they’d say ‘Yah-shoo, yah-shoo. Just be quiet.’ The word is a combination of Russian and Croatian. A guy on my street took that and gave me the name Yatcha, or Yatch. The name became very popular in Endicott.”5 To anyone who followed high school athletics in Endicott, in fact, it became a household word.

“My hometown is triple cities – Binghamton, Endicott, and Johnson City. They had a Class A Yankee farm team named the Triple Cities Triplets. When I was 12 I skipped school because the Yankees came in to play the Triplets. I ran nine miles to the ballpark, which was in Johnson City, with no money in my pocket. I go to the entrance of the ballpark and the gate man asks, ‘Where is your ticket?’ I said, ‘You have to pay to watch baseball?’ I didn’t know it was professional and you’ve got to pay.

“I backed away and went down to this green fence. Usually in them days the old ballparks had a green painted fence. There happened to be a knothole in that fence. I looked through that knothole and admired my great ballplayer of the New York Yankees, Joe DiMaggio. He was my big hero.”6

The date was Friday, May 27, 1938. With the Yanks leading 10-2, the game ended after seven innings because hundreds of kids swarmed onto the field seeking autographs from Lou Gehrig and DiMaggio. Logan said he was not one of them. Asked what he remembered from that game, he said, “Number 5, pinstripes. All I saw was number 5. It was an imagination dream. I didn’t see no part of the game. I wasn’t interested in no one but Joe DiMaggio.”7

After the game, Logan recalled, “I had to run nine miles back home to be asked by my mother, ‘How was school?’ I said, ‘Excellent.’ Meanwhile I did exactly what I wanted to do, to see my big hero, Number 5 of the New York Yankees. I had the dream of someday playing for my hometown, for the Triplets, to play professional ball. If I could make the Triplets ball team, maybe I could possibly advance to a higher classification.”8

In an interview 70 years later, Logan still felt a twinge of conscience for not telling his parents the whole truth about that day. “I didn’t lie to them, but I didn’t tell them. … My parents never knew what sports was. I had a brother that taught me baseball, taught me football, taught me the finer points. I was a batboy for his semipro team. They played every week. Then he played for his factory team, Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company. Anytime they had practice, I was there instead of hitting the books. I was playing with older guys. What happened is, I learned sports is a way of surviving. Back in them days, you could get scholarships.”9

Not surprisingly, Logan did receive scholarship offers. Dewey Griggs, the baseball scout who ultimately signed Logan for the Boston Braves organization, said, “I knew Johnny was a natural the first time I laid eyes on him. Take a look at his hands. They’re big and quick paws, ideal for a shortstop. But then Johnny excelled in any sport. I remember watching him perform at halfback one year during the New York all-state playoffs. That kid was a wonder at football.”10

As a junior at Union-Endicott High School, Logan became one of the few members of the Orange Tornado, as the school’s teams were called back then, to earn major letters in four sports: football, basketball, baseball, and track. Then as a senior, in an undefeated football season shortened to seven games by a polio epidemic, Logan scored 18 touchdowns, three times scoring four in one game, and passed for four others. In their only close game, a 6-0 battle in the mud in the season finale, Johnny scored the only touchdown and protected his team’s victory with two pass interceptions.

Logan’s gridiron heroics attracted college scholarship offers. “I was pretty good,” he said, not boastfully but without false modesty. “I had scholarships (offers) to Syracuse, Colgate, Duke, Notre Dame. We had an assistant coach named Johnny Murphy, from Notre Dame. He was the spark plug of coaching. Ty Cobb (Harold Vernon Cobb) was the head coach, but to learn football, it was Johnny Murphy.

“I think Ty Cobb convinced him that I could be a lot better baseball player than football player because of injuries. (Cobb also coached the baseball team.) I only weighed about 160 pounds then. I’d get crushed by some of them bullies. I never liked football. To me it was an animal game.”11

Logan summarized his high-school career. “I played basketball, football, baseball, golf, and I ran track. Five-letter man. But you know what I did wrong? I didn’t have enough time to look at my schoolwork. After school all I did was go out and play sports with my teammates.”12

Johnny’s main sport, though, was always baseball. “When I was 15 or 16,” he said, “every Sunday I’d take a Greyhound bus 40 miles to Homer, New York, to play semipro ball against college boys from Cortland State Teachers College.” The manager and GM of Logan’s semipro ballclub was Dewey Griggs, who in 1947 would become the New York state and Canada scout of the Boston Braves.

“This is the honest truth,” Johnny insisted. “The first workout in Homer, New York – I took a bus ride there – I meet Dewey Griggs. He approached me and said, ‘Logan, I’ve been hearing a lot of things about you, and we’re gonna have a workout.’ I said, ‘Fine.’ I went in the dugout – a pretty nice little ballpark there in Homer. I put my little jersey on. I looked in my satchel – two left-footed shoes! So I laced my left foot good, then put my other left shoe on my right foot. He said, ‘Logan, you ready to work out?’ I said, ‘Yep, let’s go.’

“He said, ‘What position?’ I said, ‘Shortstop.’ So there I am, working out, being a shortstop for about 15 minutes. He hits me groundballs to my left, to my right. About 15 or 20 minutes, and I handled it. Finally we sat in the dugout, and I’m all puffed out, sweating. He said, ‘What’s with your shoes?’ I said, ‘What’s wrong with them?’ He said, ‘You’ve got two left-footed shoes.’ The next time I showed up for a ballgame, there was a brand-new pair of shoes sitting there. So that’s one way I got a brand-new pair of shoes without no money. By making a mistake.”13

Logan graduated from Union-Endicott High School in January 1945. His athletic career was put on hold immediately. “I went in the Army right out of high school,” he said. “I was drafted. I went to Camp Wheeler, Georgia. I met a great man named Bobby Bragan. He was the manager of the Camp Wheeler baseball team. He’s the guy that taught me how to play baseball.”14

Logan served in the Army in 1945 and 1946, which included duty in Osaka, Japan. After 18 months he was honorably discharged. That made him eligible for benefits under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the G.I. Bill. Like more than two million other former soldiers, Johnny used those benefits to further his education.

“I went to college for a year and a half,” he said. “I was a veteran, an Army boy, with no money. I had the privilege of receiving the G.I. Bill of Rights and going to college and getting $75 a month. I went to an extension college in Endicott, an extension of Syracuse University, the one that became Harpur College.”15 What did he major in? “Sports,” he answered with a grin.16

Logan’s excursion into the halls of academe ended in early 1947 when his old friend Griggs, recently hired as a scout by the Boston Braves, signed him to a minor-league contract. The signing of Logan was the first of Griggs’s four important contributions to the Milwaukee Braves’ 1957 World Series championship team. The others were, in order, Bob Trowbridge, Wes Covington, and Henry Aaron.

Johnny remembered, “I signed my contract for $2,500. In them days it was big money. The first thing I did was I gave my mother $1,500 and I kept a thousand. My family was conservative. They were poor in them days. A thousand dollars was like a million.”17

The happy young shortstop entered the Braves organization with the Class B Evansville Braves. The Braves told him, “You’ve got a good manager named Bob Coleman. If he recommends you, someday you’ll be in the big leagues.” Logan recalled, “Bob Coleman got me 2,500 bucks. He always had a German police dog. That was his buddy. When we went to the ballpark, that dog was always there.”18

Playing in Bosse Field in Evansville, in the Three-Eye (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa) League, Logan wasted no time in making his mark. He tripled in his first game, smashed an inside-the-park homer in his third game, and quickly earned the Evansville Courier’s description as “the Braves’ super-shortstop.”19 He was chosen to the league’s All-Star team and finished the season with a .331 batting average.

Logan’s performance in Evansville earned him an invitation to spring training in Bradenton with the Braves in 1948. “I thought I had a good chance of making the Boston Braves,” he recalled.20 To do so, he had to beat out a sensational young shortstop of the 1947 Triple-A Milwaukee Brewers, Alvin Dark.

Johnny remembered, “Seeing Dark and seeing myself, I thought I had a good chance. Unfortunately, Dark was a good hitter. He could hit that ball to right field. I could beat him on defense, but back in the ’40s and ’50s, everybody was a good defense man.”21 Dark became the Boston shortstop in 1948, earned Rookie of the Year, and helped the Braves win the NL pennant. Logan took over for Dark in Milwaukee, in the American Association, earning $400 a month.

Johnny said, “I was told, ‘You’re gonna love Milwaukee. It’s the capital of beer.’ I can remember coming to Milwaukee in 1948, living at the Wisconsin Hotel for five dollars a day. A beer was ten cents a glass. I remember Fazio’s, on Jackson Street. The reason why I got to know Frankie (Fazio) is, after a ballgame, we’d have a big dish of spaghetti, all the Italian bread, butter, and a salad. Frankie would always send us ballplayers a bottle of beer. We ate spaghetti almost every day for a buck and a quarter.”22

The jump from Class B Evansville to Triple-A Milwaukee was too large for Logan. A month into the season the Milwaukee Sentinel bluntly reported, “Johnny is again playing bad ball at short. Logan made only four hits in the last 27 at-bats, and that isn’t good enough for this league.”23 He spent some time at Pawtucket (Class B), and at Dallas, Texas, where he enjoyed immediate success. After his third game, the Dallas Times Herald wrote, “Johnny Logan, playing short, roamed that side of the infield like a major leaguer.”24

Logan batted .283 in his five weeks as a Dallas Rebel. “We missed the playoffs by maybe a game or two,” he said.25 In 1949 and 1950 he played every game as the Brewers’ shortstop. After a good spring training in 1951, he earned a place in the Opening Day lineup of the Boston Braves. “My first major-league ballgame was against the New York Giants,” he remembered, “against Larry Jansen and Bobby Thomson and Don Mueller and Alvin Dark. I recall myself getting 1-for-3 and playing errorless ball. Boy, was I happy!”26

Logan’s elation was short-lived. Two days later, in the third game of the season, still against the Giants, “I’m in the on-deck circle,” he recalled. “I hear from the dugout, ‘Hey, Logan, come back to the dugout.’ So I was thinking, maybe they’re going to tell me what this pitcher’s throwing. Billy Southworth, who was the manager then, came over and put his arm around me. He said, ‘We’re taking you out for a pinch-hitter.’ And there I am, waiting for an opportunity. Two on, two out, my third game in the big leagues. I’m very pepped up, and then – I was shocked for being taken out.

“See, Billy Southworth was an experienced manager. He believed in experienced ballplayers. He didn’t believe in building up rookies.”27 On May 12 Southworth sent Logan down to Milwaukee. On June 20 Tommy Holmes replaced Southworth as Boston’s manager. Two weeks later Logan was recalled by the Braves, but even though he was back in the big leagues, he played in just 51 games during the rest of the season.

At the time Johnny returned to the Braves on the Fourth of July, the Milwaukee Journal wrote, “Logan had an amazing fielding record with the Brewers. He had only one error in 57 games this season and handled 264 chances.”28

Opening Day 1952 found Logan back in Milwaukee playing shortstop for the Brewers. On Memorial Day weekend, Holmes was replaced by Charlie Grimm. “Jolly Cholly’s” first managerial move was to send down Buzz Clarkson and call up Logan and insert him in the shortstop position. “Charlie Grimm liked me,” Logan explained. “I played for him in the minor leagues in Milwaukee. Charlie Grimm gave me my chance there in Boston.”29

Logan started the rest of the games that season and rewarded Grimm’s confidence in him by batting .283 and leading the NL in fielding for the first of three consecutive seasons. In 1953 Logan and the rest of the Braves made the historic shift to Milwaukee. “I spent five years trying to get out of Milwaukee,” Johnny jokingly told a reporter. “I finally get out, so what happens? I’m going back again.”30

Johnny had a well-earned reputation as a battler, a fighter who never backed down from anyone. Among his fistic rivals during his years as a Brave were Jim Greengrass, Johnny Temple, Hal Jeffcoat, and Don Drysdale. All except Temple were considerably larger than he was. Fortunately for Johnny, he had teammate Eddie Mathews to back him up. “I’d start the fight; Eddie would finish it,” Johnny said. “I’m a lover, not a fighter.”31

After the 1953 season, Logan took a bride. On October 24, in Milwaukee’s St. Thomas Aquinas Church, he exchanged vows with Dorothy “Dottie” Ahlmeyer, a beautiful young model from St. Louis. About a month after the wedding, the happy couple’s new home was completed in a working-class neighborhood on Milwaukee’s south side. The Logans lived together in that house until Dottie died of cancer in 1989.

From 1954 through 1960, Logan anchored the infield for baseball’s exciting new franchise, the Milwaukee Braves. He earned All-Star honors four times: 1955, 1957, 1958, and 1959. He helped the Braves win their only World Series in 1957. The Braves had fallen short of the 1956 pennant by one game. On June 15, 1957, however, Johnny acquired a new double-play partner who helped put Milwaukee over the top. “When Red Schoendienst joined our ball team,” Johnny recalled, “I went to his locker and hand-shaked him and I said, ‘I’m Logan, the shortstop. You’re the captain of the infield. You call the steals, who’s covering second base. Let me worry about my excellent third baseman, Eddie Mathews.’ ”32

On September 23, 1957, Logan scored the pennant-winning run for the Braves, and in the World Series that followed, featuring Aaron, Mathews, Mickey Mantle, and Yogi Berra, Logan belted the first home run. In Game Four he set an extra-inning World Series record for shortstops with ten assists. He tied Game Four with a one-out double in the tenth inning before scoring on Mathews’ home run in a dramatic Braves’ 7-5 win.

Logan and the Braves repeated as NL champs in 1958 but dropped the World Series to the Yankees in seven games. The following year Milwaukee tied the Los Angeles Dodgers for the league crown, necessitating a best-of-three playoff, which the Dodgers won in two straight games. In the deciding game Logan was knocked unconscious at second base by a football-style block thrown by Norm Larker trying to prevent a double play. When Johnny awoke, his first words were, “Did we get the guy at first?”33 (Yes, they did.)

Because ballplayers in the 1950s did not earn astronomical salaries, most of them, including Logan, needed to find employment during the offseason. Johnny said, “Miller Brewery hired guys to do public relations. They hired Andy Pafko, Billy Bruton, Lew Burdette, clubhouse man Joe Taylor, and some other guys. I went to their employment office. The man there, Bob something, said, ‘Fill out an application. We’re kind of filled up.’ I went over to Blatz and applied for a job over there. Blatz was a great beer back in them days. Meantime, I met the president of Blatz. I told him I was looking for a public-relations job, going out to taverns and going out and making speeches. I told him Miller was close to hiring me but that I wanted to be the only one working for Blatz. I must have convinced him.

“Believe me, I was a shy individual even though I was a good ballplayer. They gave me so many appearances that I got a little more confidence at getting in front of a group of people. I went to these dinners and smokers and banquets and made my little presentation. After five minutes I told them that after my speech I’d start signing autographs, and they all applauded. That’s all they wanted was my autograph. But it gave me enough confidence to get in there.”34

In December 1960 the Braves traded two good young pitchers, Joey Jay and Juan Pizarro, to Cincinnati to obtain Roy McMillan, a classic good-field, light-hitting shortstop. Logan’s days in Milwaukee were obviously numbered. On June 15, 1961, he was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for outfielder Gino Cimoli. After the 1963 season the Pirates released him.

“After three years with Pittsburgh, I went to Japan in 1964, with the Nankai Hawks. I liked Japan. They were paying me good money. But it was very difficult to communicate. We only had two minor-league ballplayers, Joe Stanka and another kid. I was the only major leaguer. (Stanka had pitched in two games for the White Sox in 1959.) They thought they had a superstar, but unfortunately, at 36 …

“But I enjoyed it. I got to know Japan a little bit – Osaka, Kobe, Tokyo. It was an experience. I took my family there. I have three kids – my Jimmy, the youngest; John (called Danny) is the oldest; and Jeffrey’s in the middle. Jimmy happened to be born on March 24, a day after my birthday. I told my wife, ‘I want him to be born in America.’ Because if you’re born overseas you can never become president of the United States. I told my wife, ‘When you feel good, you fly over.’ Then they flew over about a month later.”35

The Nankai Hawks won the Japanese equivalent of the World Series on October 10, 1964, seven years to the day after the Milwaukee Braves won their version of the “world championship.” Logan’s batting average for the year, though, was below .200. Johnny decided to end his baseball career.

“I met Ralph Barnes, the manager of radio station WOKY,” Johnny said. “It was the main station in Milwaukee back in them days. I had a sports show, getting interviews from all the big celebrities, like Vince Lombardi and Pat Harder, the referee. He played with the Chicago Cardinals. And I sold advertising to Selig Ford.”36 In 1973 Logan provided color commentary for Milwaukee Brewers game telecasts. After being appointed to that position, Johnny said, “I’m very, very speechless.”37

Following his brief broadcasting career, Logan set his course, as the old Johnny Horton song said, north to Alaska. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the largest privately funded project in US history, had just been started. Johnny wanted to be part of the project.

“It was frontier terrain,” Logan said, “but it’s not going to stay frontier terrain. I didn’t want somebody telling me how Alaska used to look.”38 On April 27, 1976, he took off to see for himself. He had told his wife he was going, but she didn’t believe him. He arrived in Anchorage, age 50, without a job and without experience. After a week of searching, he landed employment.

“I had never done welding,” Johnny said with a chuckle. “I was a welder’s helper. It was hard work, rough and tough. We lived in barracks in the wilderness. I was with dope addicts, whiskey men, beer drinkers, hard-working men. I never gambled there, never had a drink while I was there. I was like a saint. I’d see these guys in these poker games, a thousand, two thousand dollars. Some guy was gonna work all week for nothing.”39

Logan earned $11.60 an hour, time and a half after 40 hours. He worked from 6 in the morning until 6 at night, seven days a week. “They furnished your food, and they gave you your lodging,” he recalled. “I sent all my money home, my checks. My kid said, ‘Mommy, how come he’s sending so much money home? What’s he doing there?’ It was tough work, but I didn’t go there for the money. All I did was work, eat, sleep, and write postcards home. For a while I read three-day-old newspapers until I realized, what the hell did I care what was going on?”40

In 1978 Logan ran for sheriff of Milwaukee County for the third time. In 1966 he had finished a close second in the Democratic primary in a heavily Democratic county. In 1968 he ran unopposed in the Republican primary, then lost by two to one in the general election. On his third attempt, he reverted to the Democratic Party but was defeated in a landslide by the eight-term incumbent.

Logan maintained his ties to Milwaukee and to the sport he loves. In the early ’90s he operated the radar gun at County Stadium. He did scouting for the Milwaukee Brewers.

On August 26, 2005, the Milwaukee Brewers inducted Logan to their Milwaukee Braves Honor Roll in the concourse of Miller Park. On June 6, 2013, he was inducted as the 17th member of the Walk of Fame at Miller Park. In a pregame ceremony before the 1905 induction, Brewers radio announcer Jim Powell highlighted Johnny’s baseball and civic achievements. He also described Johnny, with tongue firmly in cheek, as a “superb conversationalist,” comparing him favorably to such language stylists as Dizzy Dean and Yogi Berra.41 Following are just a few oft-quoted Loganisms:

“Rome wasn’t born in a day.”

“I will perish this trophy forever.”

Ordering dessert in a restaurant, Johnny requested pie à la mode, then added, “And put some ice cream on it.”

At a banquet, Johnny introduced “one of the all-time greats in baseball, Stan Musial. He’s immoral.”

When a teammate referred to a mutual acquaintance, Johnny said, “I know the name, but I can’t replace the face.”42

And Milwaukee Braves fans will tell you that nobody will replace Johnny Logan …

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Sources

Buege, Bob, “Braves Honor Roll Adds Logan,” The Tepee newsletter, September 2005.

Chapman, Lou, “John Logan of Braves Weds Model,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 25, 1953.

____________, “Johnny Logan Recalls Old Days at County Stadium,” Baseball Digest, May 2001.

____________, “Logan Returns After Spending 5 Years Trying To Leave Town,” Milwaukee Sentinel,

March 31, 1953.

Jauss, Bill, “Adventure Drew Logan to Alaska Pipeline,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1976.

Thisted, Red, “Brews Bank on Wright,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 25, 1948.

Walfoort, Cleon, “We Gave Our Best,” Milwaukee Journal, September 30, 1959.

“Morning Briefing,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1976.

“Quotebook,” Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1973.

“Season’s No. 1 Crowd Sees John Logan Star,” Evansville Courier, June 16, 1947.

“Wall Gives Brewers Even Split; Logan Is Recalled by Braves,” Milwaukee Journal, July 5, 1951.

Binghamton Press & Sun Bulletin, May 1938.

Dallas Daily Times Herald, June 15-August 15, 1948.

Endicott Daily Bulletin, June 1-December 31, 1944.

Evansville Courier, April 1-August 31, 1947.

Milwaukee Journal.

Milwaukee Sentinel.

Baseball-reference.com.

In-person interviews with Johnny Logan: December 6, 2005; May 17, 2006; March 23, 2007.

Notes

1 Johnny Logan, in-person interview, March 23, 2007.

2 Johnny Logan, in-person interview, May 17, 2006.

3 Johnny Logan, in-person interview, December 6, 2005.

4 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

5 Ibid.

6 Logan interview, March 23, 2007.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Lou Chapman, “John Logan of Braves Weds Model,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 25, 1953.

11 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

12 Logan interview, December 6, 2005.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Logan interviews, December 6, 2005, and March 23, 2007.

16 Logan interviews, December 6, 2005, and March 23, 2007.

17 Logan interviews, December 6, 2005, and March 23, 2007.

18 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

19 “Season’s No. 1 Crowd Sees John Logan Star,” Evansville Courier, June 16, 1947.

20 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

21 Ibid.

22 Logan interview, December 6, 2005.

23 Red Thisted, “Brews Bank on Wright,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 25, 1948.

24 Dallas Daily Times Herald, June 29, 1948.

25 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

26 Logan interview, December 6, 2005.

27 Ibid.

28 “Wall Gives Brewers Even Split; Logan Is Recalled by Braves,” Milwaukee Journal, July 5, 1951.

29 Logan interview, December 6, 2005.

30 Lou Chapman, “Logan Returns After Spending 5 Years Trying To Leave Town,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 31, 1953.

31 Lou Chapman, “Johnny Logan Recalls Old Days at County Stadium,” Baseball Digest, May 2001.

32 Logan interview, December 6, 2005.

33 Cleon Walfoort, “We Gave Our Best,” Milwaukee Journal, September 30, 1959.

34 Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

35 Ibid.

36 Logan interview, March 23, 2007

37 “Quotebook,” Los Angeles Times, February 4, 1973.

38 Bill Jauss, “Adventure Drew Logan to Alaska Pipeline,” Chicago Tribune, August 15, 1976.

39 “Morning Briefing,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1976; Logan interview, May 17, 2006.

40 Bill Jauss, “Adventure Drew Logan.”

41 Bob Buege, “Braves Honor Roll Adds Logan,” The Tepee newsletter, September 2005.

42 Baseball-reference.com.

Full Name

John Logan

Born

March 23, 1926 at Endicott, NY (USA)

Died

August 9, 2013 at Milwaukee, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.