Jose Cruz

“One of the best and most underrated players I have ever seen.” — Joe Morgan, Hall of Famer

“A Puerto Rican legend whose brilliance equals that of the stars.” — Honduran sportswriter Greg Moraga

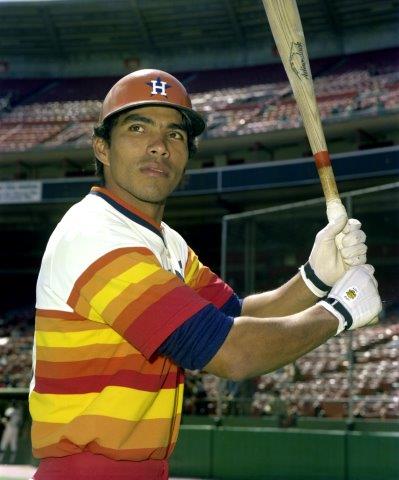

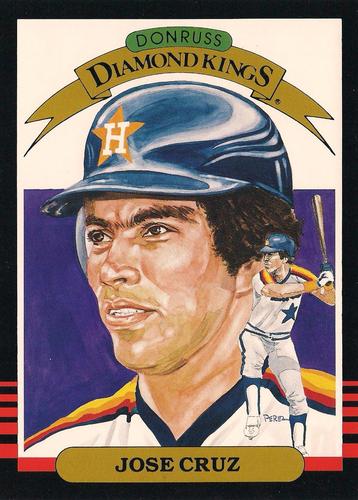

Growing up in Houston in the 1970s and ’80s, every kid idolized Astros left fielder José Cruz. They dreamed of watching him, meeting him, and getting his autograph. One of the most popular players in the history of the franchise, Cruz is equally adored in his native Puerto Rico, as widely known as the great Roberto Clemente. His consistently solid work ethic, good character, and respect for the game and his fans have won him admiration from young and old alike.

Growing up in Houston in the 1970s and ’80s, every kid idolized Astros left fielder José Cruz. They dreamed of watching him, meeting him, and getting his autograph. One of the most popular players in the history of the franchise, Cruz is equally adored in his native Puerto Rico, as widely known as the great Roberto Clemente. His consistently solid work ethic, good character, and respect for the game and his fans have won him admiration from young and old alike.

Nothing exemplifies these traits more than the story of young fan-turned-ballplayer, Dave Dellucci. On a Fox Sports Diamondbacks Live pregame show on April 26, 2012, interviewer Todd Walsh introduces Arizona Diamondbacks outfielder Dave Dellucci to his childhood hero, José Cruz, now the Houston Astros first-base coach. Dellucci tells the heartfelt story of driving to his first major-league baseball game, in Houston with his uncle from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. About 5 years old, Dave was carried on his uncle’s shoulders down the sidelines to meet some Astros ballplayers. The player who signed his miniature baseball bat that day was José Cruz. Little David never forgot. He began rooting for “Cheo” Cruz and developed a stronger interest in baseball as a result. When possible, Dave always chose to wear Cruz’s number 25 when he played. He was thrilled to be introduced to his idol, José Cruz, and Cruz was touched by Dellucci’s story. He said he always liked “being good to everybody,” and could never “say no to the kids.”1

Born in Arroyo, Puerto Rico, on August 8, 1947, José was the eldest of three brothers who must have been born to play baseball. He was an all-around athlete at Arroyo High School, excelling in track, basketball, softball, and baseball. Cruz signed with St. Louis Cardinals scout Chase Riddle out of high school in 1966.2

After paying his dues with minor-league teams in St. Petersburg, Florida (Class A), Modesto, (A), and Little Rock (Double A), Cruz was called up to St. Louis for his major-league debut on September 19, 1970. He played in six games and got his first major-league hit, a single, off the Philadelphia Phillies’ Rick Wise on September 19. He started the 1971 season with the Triple-A Tulsa Oilers of the American Association, managed by Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. He roared to a .327 average in the first 67 games with the Oilers, and was called up to the majors for good.

In 1973 spring training, Cheo found himself in an all-Cruz outfield for the Cardinals, playing an exhibition game against the New York Yankees. Younger brothers Cirilo (Tommy, b. 1951) and Hector (Heity, b. 1953) had been signed by the Cardinals in 1969 and 1970, respectively, and would make their major-league debuts in the 1973 season. While a good many brothers have played professional baseball, the Cruz trio was one of only a handful of sets of three or more baseball brothers to be in uniform at the same time. Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst was impressed with them, telling sportswriters, “They’re good ballplayers. [If] they have six brothers back home, and if they come to town, I’ll play them, too.”3

José Cruz was not destined to stay long in St. Louis. He was sold to the Astros in a cash deal on October 24, 1974. Cruz debuted for the Astros on April 7, 1975, in the Astrodome, going 3-for-4 with a home run and three RBIs in a 6-2 victory over the Atlanta Braves. The Astros’ spacious Astrodome was a pitcher’s haven, especially against the Astros weak offensive lineup.

That bland offense began to shape up, though, and Cruz was a large part of its success. In 1977, he emerged as the best hitter on the team, batting .299 with 17 home runs, 87 RBIs, and 44 stolen bases. Fans loved how J. Fred Duckett, the Astros public-address announcer, drew out Cruz’s name when he came up to bat, and they joined in a chorus of “CRUUUUUUUUUUUUUUZ!” This created a great relationship between the two; José appreciated Duckett’s gesture, and when he left the Astros, he gave Fred one of the bats from his last game, signing “Cruz” with about 15 U’s, according to Duckett.4

Tal Smith, often called the architect of the Astros for his role in constructing both the team and the Astrodome, had returned to the Astros in 1975, bringing Bill Virdon with him as manager. His challenge was to build a talented nucleus of young players mixed with experienced veterans. He wanted pitching, speed, and defense — necessities in the spacious Astrodome. Smith didn’t need “stars.” He wanted versatility and flexibility.

To outfielders José Cruz and Enos Cabell, called the “glue of the team” by sportswriter Jack Hand of the Houston Chronicle, and an already talented pitching staff including Larry Dierker, J.R. Richard, Dave Roberts, and Joe Niekro, Smith added other versatile talent, including Cesar Cedeño, pitcher Joaquin Andujar, and a strong veteran presence in Joe Morgan.5 Cruz and Morgan were like-minded, both interested in the team win, not personal recognition. Virdon brought a new level of efficiency to the team, expecting every player to run all-out to first base, even the pitchers. “This started a new mindset, a changing of the guard,” said Cabell when he appeared on a panel at the SABR convention in Houston in 2014.

Cheo Cruz was already a leader in that philosophy, frequently sacrificing personal stats to move runners ahead. “I always play for the team,” Cruz said. He never tried to pull the ball because the Dome “wasn’t a place for home runs.” Cruz’s batting coach on the Astros, Deacon Jones, observed that, “Cheo worked tirelessly at hitting to the opposite side,” which made him one of the best clutch hitters in baseball. In fact, in Smith’s opinion, the 1980 outfield was “the absolute best in character and performance.”6

Cruz had hit in 15 straight games early in the 1979 season, from April 21 to May 9, raising his batting average from .267 to .340. He led the Astros in many offensive categories that year: batting average (.289), games (160), doubles (33), home runs (9), RBIs (72), and walks (72), as well as in game-winning RBIs (14). In 1980 he was selected to play in his first All-Star Game, was voted Astros team MVP, and received his second straight Roberto Clemente Award.7

However, the 1980 season held misfortune, too. Midway through the season the Astros suffered the tragic loss of phenomenal young pitcher J.R. Richard to a stroke. And though Cruz’s memories of the Astros-Phillies playoffs were unforgettable, as the first-ever championship series for the Astros franchise and himself (he batted .400 and received a record three intentional walks in Game Three of the 1980 NLCS), the outcome was dismal. The best-of-five series included four extra-inning games, two controversial plays in Game Four,8 and in Game Five, with the Astros six outs from the World Series, Cruz having helped tie it up at 7-7, doubles by Phillies Del Unser and Garry Maddox led to a heartbreaking 8-7 loss in the 10th.

In 1981 Cruz continued to excel, leading National League batters throughout the strike-interrupted season.9 He led Astros teammates in games played, at-bats, runs scored, hits, and RBIs. He had a great defensive year in his second full season in left field. Cruz hit in three out of five Division Series games against the Los Angeles Dodgers, with the Astros winning two home games to start but losing the last three in Los Angeles. He was named Puerto Rico’s 1981 Pro Athlete of the Year.

The 1982 and 1983 seasons showed Cruz to be one of the most durable Astros, rarely missing a game. By the end of the 1982 season, he was among the top six in every Astros category for career offense; his .291 was second all-time to Bob Watson in batting average and he ranked third to Cedeño and Morgan, with 213 stolen bases. In 1983, he put together a monumental season, going down to the wire in a battle for the National League batting title. He hit a scorching .375 in July, and averaged .341 for the second half of the season. While he came in third for the batting title at .318, he tied Andre Dawson of the Montreal Expos for most NL hits (189), was sixth in on-base percentage (.385), seventh in RBIs (92), and ninth in slugging percentage (.463). The 1983 season saw Cruz drive in his 1,000th run, on his 36th birthday, August 8, and rap out his 1,800th hit two days later

Cruz continued to excel in 1984, again finishing the season at the top of National League offensive categories; he tied for fifth in hitting (.312), third in triples (13), fifth in hits (187), sixth in runs scored (96) and on-base percentage (.381), seventh in RBIs (95), and ninth in walks (73). He became the Astros team MVP for a record fourth time. For the second consecutive season he was named to The Sporting News Silver Slugger team as one of the National League’s top three offensive outfielders. He passed Joe Morgan’s former franchise record for triples (63) with 68, and tied the club record for runs scored in one game (4).

Cruz continued to excel in 1984, again finishing the season at the top of National League offensive categories; he tied for fifth in hitting (.312), third in triples (13), fifth in hits (187), sixth in runs scored (96) and on-base percentage (.381), seventh in RBIs (95), and ninth in walks (73). He became the Astros team MVP for a record fourth time. For the second consecutive season he was named to The Sporting News Silver Slugger team as one of the National League’s top three offensive outfielders. He passed Joe Morgan’s former franchise record for triples (63) with 68, and tied the club record for runs scored in one game (4).

By 1985, Cruz had finally been discovered by baseball fans across America. It seemed that everywhere the Astros played, some reporter wanted to do a story on him. At least one writer referred to him as “the most underrated ballplayer of the last decade.”10 But fame was so new to the always genial Cruz that he even complained a bit about the overwhelming presence of the press to surprised Astro teammates and staff. What was remarkable was that, at age 37, his career seemed to be getting better. Astros manager Bob Lillis asserted that Cruz continued to have the body of a younger man because he was continually in shape. After playing in the Puerto Rican winter league he came back to spring training ready to go, said Lillis.11 Cruz said, “That’s all mental. I’ve been playing winter ball for 15 years. Then I take two or three weeks off and I don’t even need spring training.” Lillis liked the fact that Cruz was willing to play anywhere. He didn’t want to have a day off, said Lillis. He just loved to play.12

Latin players had often had trouble getting recognition, even stars like Clemente, and Cruz was no exception. Writers hesitated to tackle the possible language barrier, and multiple players named Cruz (including his brothers Hector and Tommy) added confusion. But Chicago Tribune sportswriter and columnist Robert Markus concluded, “People have been adding the numbers and they add up to stardom.”13

Cruz turned 38 at the end of the 1985 season, leading the franchise batting lists, but starting to show his age. In August 1986, he was hot, hitting .327 and driving in 17 runs for the Astros. That season he had enough stamina left to aid the Astros playoff efforts, but by 1987 a much younger Gerald Young was competing for his spot in left field. Many Astros fans were disappointed when Cruz was not able to complete his career in Houston; when his contract was not renewed he played a final partial season with the New York Yankees. When he left the Astros, he was first or second in virtually every offensive category. His 80 triples (as of 2017) remained a franchise record.

Cruz also holds a few rather extraordinary distinctions: Out of 7,448 at-bats, he was hit by a pitch only three times in his career in Houston (once each in 1975, 1982, and 1983). He seemed to have developed a unique ability to avoid getting hit.14

The second noteworthy record involves a play resulting in major-league baseball’s millionth run scored.15 Major League Baseball was tracking the scoring of this milestone run. As players closed in on the milestone, the clock times of run-scoring were being monitored across the major leagues. In the second inning at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on May 4, 1975, Astros first baseman Bob Watson walked, then stole second during José Cruz’s at-bat. Cruz also walked. Then Astro Milt May hit a home run off San Francisco Giants pitcher John Montefusco, scoring both Watson and Cruz. Watson crossed the plate at precisely 12:32 P.M. with the millionth run, followed by Cruz and May, who almost crossed paths, which would have nullified the run. Watson reached home only three seconds before Cincinnati Reds shortstop Dave Concepcion scored from his homer off Phil Niekro of the Atlanta Braves in Cincinnati.

As Cruz’s career drew to a close, baseball fans and writers attempted to evaluate his impact on the game. Some, like Puerto Rican baseball writer/historian Edwin Kako Vasquez, simply said that Cruz was a “great natural ballplayer,” and that he had many fine attributes, the best of which are “his good character, his great friendship, and the fact that he is always ready, always prepared.”16

Others, like Bill James, who in 1987 introduced the concept of “park effects” in his annual Baseball Abstract, tried to analyze Cruz’s stats and determine the effect of the Astrodome on his hitting. He concluded that the playing field is not level when it comes to the effects of home ballparks on player statistics. In other words, Cruz’s offensive numbers would have been much better if he had not had to hit in the Astrodome, since his on-the-road statistics were considerably better than at home. Astros fans had long before figured this out: Cruz was a much better hitter than most people realized.17

The writers of Total Baseball also developed an objective method for evaluating hitters, called the Total Player Rating (TPR). It is expressed in a number that attempts to show how a player performs either above or below what an average player might produce. It is also adjusted for park effects. Cruz’s TPR of 28.7 is not only very good, but places him at number 139 on the all-time major-league player list, and above several already in the Hall of Fame. While many may not have voted Cruz into the Hall of Fame, few would dispute that he never received the credit he deserved.18

In 1992 José Cruz’s number 25 was retired by the Astros, and in 1997, he was named first-base coach when Bob Lillis became manager. However, now came the time for Cheo’s sons to share a little of the limelight. Baseball had always been a family affair in the Cruz house, and now Cruz and his wife of 30 years, Zoraida (Vasquez), had time to watch sons José (Cheito or Little Cheo) Jr., and José Enrique shine — first, at Rice University, where both sons excelled in baseball. After some years of taking classes around their baseball careers in order to keep a promise made to their mother, both Cheito and Enrique graduated in May 2013 with degrees in sports management.19 José Jr. had been drafted in the first round in 1995 by the Seattle Mariners, and played in the major leagues for 12 years.

Enrique Cruz, drafted in 2003 by the New York Yankees, moved around for eight seasons in the minors, and then became the director of Cruz Baseball Camps. Both sons played in the Puerto Rican winter leagues. In 2003-04 Cheo Cruz was voted Manager of the Year for piloting the Ponce Lions (and both sons) to the Roberto Clemente Professional Baseball League Championship20 and later to victory in the 2004 Caribbean World Series. One of Enrique’s favorite moments was when he and José Jr. hit back-to-back home runs during the 2003 winter season,21 a repeat of an earlier feat when father José Sr., playing for Houston, and Uncle Cirilo “Tommy” Cruz, playing for the Chicago Cubs, both hit homers in the same game on May 4, 1981.22 When Carlos Beltran was traded to the New York Mets at the end of the 2004 season, Cheo suggested that the Astros sign his son Cheito to fill his spot in the outfield.23 In the 2006 World Baseball Classic, José Sr. coached the Puerto Rican national team, including José Jr., to the second round.

In 1992 Cheo Cruz’s number 25 was retired by the Astros. It was a special day for Cruz, but did not signal the end of the Cruz family’s contribution to baseball. They have contributed six players to US professional baseball,24 Cheo and brothers Hector and Tommy, sons Cheito and Enrique, nephew Cirilo (Hector’s son), and possibly more, with grandson Trei (son of José Jr.) a middle infielder playing at Rice University, scheduled to graduate in 2017, and attempting to “keep the Cruz legacy going.”25

The 2017 baseball season marked José Cruz’s 34th campaign with the Astros. He played 13 seasons in the outfield, coached for 13 more, spent five years as a special assistant to the president and then as a community outreach executive.

Last revised: June 13, 2018

This biography appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted baseball-reference.com, CalltothePen, LatinoBaseball.com, MLB.com, SABR.org, YouTube.com, and the following:

Puerto Rico Herald, http://puertoricoherald.org/PRBtnArch/PRBtnArch2002/PRSportsBeat.

AstrosDaily.com, http://astrosdaily.com/files/team/cruz/cruz.html.

Moraga, Greg. “José “Cheo”Cruz, leyenda boricua que brillo igual a los Astros.” CatrachoSports.com, June 14, 2015.

Special thanks to my daughter, Mary K. Moritz, for assistance with Spanish translation.

Notes

1 See entire Walsh/Dellucci/Cruz interview at: youtube.com/watch?v=Psoi5btQK9k.

2 Riddle since 1963 had been the Cardinals’ scouting supervisor for the Southeastern United States, Puerto Rico, and Latin America.

3 Samuel O. Regalado, Viva Baseball!: Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 154.

4 David Barron, “J. Fred Duckett Remembered for Cruuuuz Intro,” Houston Chronicle, June 26, 2007.

5 Joe Morgan had been signed to the Colt .45s in 1963, and appeared two years later in the lineup for the renamed Astros’ first game in the Astrodome, April 9, 1965, vs. the New York Yankees. Traded to the Cincinnati Reds in 1971, where he helped win two World Series in 1975 and 1976, he was reacquired from Cincinnati by the Astros in 1980.

6 All quotations from a 1980 Astros panel at the SABR convention in Houston in 2014.

7 The Roberto Clemente Award is presented each year to the major-league player who most exemplifies baseball, sportsmanship, and local humanitarian work. Each of the 30 clubs selects a team winner, who then becomes a candidate for the national award. Cruz won the team award in 1979 and 1980.

8 Both were disputes over trap-or-catch situations. See entire Game Four at: http://youtube.com/watch?v=-2kkfWU0zz4.

9 The strike began June 12, 1981; an agreement was reached on July 31; and play resumed with the All-Star Game on August 9, followed by the remaining regularly scheduled games. A total of 713 games had been canceled. See also: thesportsnotebook.com/downloads/download-the-story-of-the-1981-mlb-season/ for a summary of the unusual and not-quite-fair split-season format adopted by MLB after the strike to determine playoff teams.

10 Robert Markus, “Meet Best Cruz of All, Houston’s Jose,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1985. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1985-05-26/sports/8502020814_1_jose-cruz-houston-astros-left-fielder-bob-lillis

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 “Cruz Control: Avoiding the Plunk,” astrosdaily.com/files/team/cruz/cruz.html.

15 Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co., Inc., 1997), 627.

16 Enrique Vasquez, Tribute to Cruz on Television, Houston Channel 7, in Spanish: youtube.com/watch?v=Dd4q410xWro Uploaded on May 15, 2009. Retrieved on November 11, 2016.

17 “The Astrodome: Where Fame Went to Die,” AstrosDaily.com: Jose Cruz Tribute, http://astrosdaily.com/hall/Cruz_Jose.html.

18 Ibid.

19 Richard Justice, “Cruz Family to Enjoy a Proud Day Together,” MLB.com, http://m.mlb.com/news/article/47139994/jose-cruzs-sons-jose-jr-and-enrique-to-graduate-from-rice-university/.

20 The Liga de Béisbol Profesional Roberto Clemente or LBPRC was formerly known as the Puerto Rico Baseball League, or Liga de Béisbol Profesional de Puerto Rico, and is the main professional baseball league in Puerto Rico.

21 Playing for the Caguas Creoles (las Criollos de Caguas).

22 Lyle Spatz, ed., The SABR Baseball List and Record Book: Baseball’s Most Fascinating Records and Unusual Statistics (New York: Scribner, 2007), 64.

23 Jose de Jesus Ortiz, “Cruz Suggests Astros Pursue His Son in Trade,” Houston Chronicle, January 14, 2005.

24 The Cruz family is tied with several on the list of five or more family members in baseball, including the Perez and Alomar families, with six; fewer than 20 other families have more than six. Baseball-Reference, http://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Largest_Baseball_Families.

25 Mark Berman, Houston’s Fox 26, September 24, 2015. http://fox26houston.com/sports/24283728-story.

Full Name

Jose Cruz Dilan

Born

August 8, 1947 at Arroyo, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.