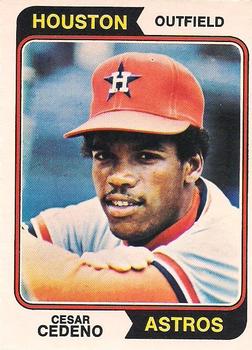

César Cedeño

“At 22 Cedeño is as good or better than Willie was at the same age. I don’t know whether he can keep this up for 20 years, and I’m not saying he will be better than Mays. No way anybody can be better than Mays. But I will say this kid has a chance to be as good. And that’s saying a lot.” — Leo Durocher, May 19731

“At 22 Cedeño is as good or better than Willie was at the same age. I don’t know whether he can keep this up for 20 years, and I’m not saying he will be better than Mays. No way anybody can be better than Mays. But I will say this kid has a chance to be as good. And that’s saying a lot.” — Leo Durocher, May 19731

Such praise may seem absurd, but consider that at age of 22, Cedeño completed his second straight year of batting .320, hitting 20-plus home runs and stealing 50-plus bases, demonstrating that rare combination of power and speed, the second player in history to reach those levels in home runs and stolen bases in the same season.2 Cedeño could do it all – run, hit, hit with power, had a strong arm and made spectacular catches playing center field. So popular was Cedeño that the Astrodome was called “César’s Palace.”

César (C.C.) Cedeño (pronounced seh‐DANE‐yo) was born on February 25, 1951, in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic to Diogenes and Juana (Encarnacion) Cedeño. By age 11 he was working in the same nail factory as his father. His father bought a grocery store and wanted César to help out and run errands instead of wasting his time playing baseball. Another article suggested that he wanted César to help his mother out around the house. César’s mother was supportive of his ballplaying and bought him a glove and shoes without her husband’s knowledge. As a 12-year-old, César practiced catching fly balls at night by throwing a ball in the air higher than the street light, then on its descent, tried to catch the ball while at the same time avoid getting hit by it. The neighbors thought he was crazy. When he was 14, César quit school to work full time at the nail factory. A year later he returned to Fidel Ferrer School.

The Dominican Republic was open territory and draft rules did not apply and players were signed as free agents. In the fall of 1967, Houston Astros scouts Pat Gillick and Tony Pacheco were searching the Dominican Republic for talent. Pacheco told how they discovered the 16-year-old Cedeño: “I was managing in the winter leagues and our game was rained out, but a local game was being played. We went to watch some other fellow, but the manager told us to look at Cedeño.”3 Gillick said, “We noticed this kid and liked the way he moved, his actions and his size. We saw him throw and then we saw him go up and get a hit and go up and get another hit. We decided we wanted to look at him. After the game, we arranged for him to go with us and some more players to San Pedro, about 60 miles away, for a workout Monday morning.”4 The location was arranged to avoid being noticed by other scouts. After the tryout Gillick decided he wanted to sign Cedeño and met with his father because Cedeño was a minor. Gillick discovered that the St. Louis Cardinals had offered Cedeño $1,000 to sign, but his father refused. Gillick offered up to $1,500, but the negotiations stalled. Then Gillick’s friend on the island, Epy Guerrero, warned him that Cardinals scout Diomedes Olivo was on his way and would arrive in 15 minutes. Gillick then doubled his offer to $3,000 and Cedeño’s father accepted. When Olivo arrived, Gillick held up the contract and said, “You’re a few minutes too late.”5

“When I was 15, I was still sitting on the bench in a Santo Domingo junior league,” Cedeño said, “and we only played on Sundays. I probably hadn’t played as many as 100 games when I was signed.”6 He was assigned to the Covington (Virginia) Astros of the rookie Appalachian League. “I worked hard to learn English. I watched TV – cowboy movies and cartoons. I learned English from the Flintstones,” said Cedeño in an interview.7 He batted .374 in 36 games and was promoted to the Cocoa Astros of the Class-A Florida State League, where he batted .256 in 69 games.

In 1969 Cedeño spent a full season playing for the Class-A Peninsula (Hampton, Virginia) Astros in the Carolina League. Tony Pacheco was his manager and corrected a flaw in Cedeño batting by getting him to bend his front knee when he swung his bat. Cedeño batted .274 with five home runs in 142 games and led the league in doubles with 32. That same season he played in the Winter Rookie Class in the Florida Instructional League North and batted .278 in 37 games and got rave reviews from scouts. Cedeño played well in winter league ball in the Dominican Republic, where Rico Cartyhelped him with his batting.

In 1970 Cedeño was impressive in spring training and started the season in Triple A with the Oklahoma City 89ers of the American Association. Some inside the organization felt the 19-year-old was ready to join the Astros, but others did not want to rush him. But Cedeño’s progression was quicker than anyone in the organization could have imagined. He proved to be an excellent fielder, making catches in front and behind him. Cedeño had a strong arm, hit line drives, and had power to all fields. In 54 games he batted .373 with 14 home runs and 61 RBIs. Manager Hub Kittle encouraged Cedeño to be aggressive at the plate; he walked only eight times and struck out only 26 times in 247 at-bats. Kittle compared Cedeño to Felix Millan, star of the Atlanta Braves: “Sandy (nickname given by his teammates) has those same quick wrists and he’s the same fiery competitor that Felix was when I had him at Yakima.”8

Cedeño was called up on June 20, at 19 the youngest player in the National League. He debuted that night Atlanta, starting in center field and batting third. In his second at-bat, Cedeño singled off George Stone for his first major-league hit. He added another single and went 2-for-5. Cedeño struggled his first month in the majors and was dropped to seventh in the lineup. On August 14 he crashed into the center-field wall, sprained his ankle, and was out a week. Cedeño ended the season batting .310 with 7 home runs, 42 RBIs, and an OPS of .790.

Manager Harry Walker said, “He has more natural ability than anyone in our organization. He can do everything – run, throw, hit, and catch the ball. He has fine natural instincts for the game. He has a lot to learn, but he learns quickly and you usually only have to tell him something once.”9 Roberto Clemente praised the rookie phenom: “One of the best-looking young players I’ve ever seen.”10Although he played in only 90 games, he finished fourth in the National League Rookie of the Year voting.

In 1971 Cedeño started the season in right field. The reason was unclear. Some speculated that it was to take advantage of his strong arm; the other theory was that it was meant to motivate Jim Wynn by moving him back to center field. Cedeño started out slowly, batted .186 and struck out 32 times in 129 at-bats (24.81 percent) and on May 20 was removed from the starting lineup. He returned to the starting lineup on May 31 when Wynn had a sore wrist. He was 7-for-9 with two doubles, two home runs, and six RBIs in his next two games. Cedeño rebounded from a season low .180 batting average on May 30. He said, “I’m watching the ball now. I wasn’t following the ball all the way. I was swinging hard and pulling my eye off the ball.”11 Despite the slow start, Cedeño led the National League with 40 doubles, batted .264 with 10 home runs, and led the team with 81 RBIs, but struck out 102 times.

In 1972 the 21-year-old Cedeño blossomed and there was speculation that he would be the game’s next superstar. He led the National League in batting through August,12 until he was overtaken by the hot bat of Billy Williams and finished fourth with a .320 average. Cedeño tied for the league lead with 39 doubles, hit 22 home runs, stole 55 bases, drove in 82 runs, had a .385 on-base percentage and a .537 slugging percentage. He also lowered his strikeout total to 62. Cedeño was named to his first All-Star squad, won the first of his five consecutive Gold Gloves and finished sixth in the 1972 National League MVP balloting.

It was probably natural to compare Cedeño and Clemente because their styles were similar. Both players hit to all fields with some power, not primarily home-run hitters. Both had strong arms, but Clemente’s was considered the best of all time in 1972, and both were Latinos. Both players have been described as “playing all-out baseball, with not a little flamboyance, and both were accused of hot-dogging.”13 Maury Wills said in defense of Cedeño, “When a player like Cedeño is on the other side, he’s a hot dog. When he is on your side, he plays hard and is colorful.”14

Harry Walker, who managed both Cedeño and Clemente, said, “Clemente and Cedeño are the two most exciting players in baseball today. Whether they are catching the ball, throwing it or running the bases, or batting, they do it all-out and with flair. When they are involved, you’re always on edge expecting something to happen. They make things happen.”15 Said Clemente: “I don’t think it’s fair to him. When I came up, I did not like to be compared to other players.”16 “I don’t want to be the second Clemente,” said Cedeño. “I would rather be the first Cedeño.”17 When Hank Aaron was asked who was the last player to come into the league with as much ability as Cedeño, he simply replied: “Me.”18

By 1973 Cedeño had established himself as one of the league’s best players and was voted by the fans as an All-Star Game starter. His offensive production was comparable to his previous season: He batted .320 again, finishing second in the National League to Pete Rose. He hit 25 home runs and stole 56 bases. But his runs, hits, and RBIs were down and he struck out more. Cedeno played hard, diving for line drives and running into walls, but general manager Spec Richardson was questioning his toughness: “Cedeño got hurt and stayed hurt, he can’t play with any pain.”19 Cedeno returned to the Dominican Republic to recuperate and play winter-league ball.

While there Cedeño injured his knee. He went to Houston to get it checked out and was advised to rest until spring training. Cedeño returned to the Dominican Republic. In the morning of December 11 at about 2:00 A.M., Cedeño and 19-year-old Altagracia de la Cruz checked into the Keko Motel, located in a poor section of Santo Domingo. The couple had been out drinking and Cedeño had ordered two beers. There were reports of an argument and loud noises coming from their room. A motel employee testified that a gunshot was fired about 10 minutes later. Cedeño called a motel employee and told him that “a woman has been killed,” and then fled the scene in his sports car.20 Cedeño said, “I went to my house, told my wife what happened, then went to the police. I was scared. I saw my baseball career was in danger.”21 Cedeño, accompanied by his father, turned himself into the police about eight hours later.

Cedeño was carrying a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson revolver, for which he had a permit. He told the police he had been robbed of $5,000 in jewelry and cash and needed the gun for his protection. Cedeño testified that de la Cruz asked to see the gun and when he refused, she tried to wrestle it away from him and the gun fired, resulting in her death. Cedeño was held in the local jail with three other men. The police conducted paraffin tests and concluded that only the victim had recently fired a gun. The police report stated, “It has not been possible to fix any blame on Cesar Cedeño.”22

Cedeño’s fate was in the hands of the Dominican legal system and he was held in La Fe Precinct Jail. District Attorney Maximo Henriquez Saladin brought a charge of voluntary manslaughter, which in the United States was equivalent to second-degree murder. General manger Spec Richardson and Pat Gillick came down from Houston. Cedeño’s American wife, Cora, who was at the couple’s home in Santo Domingo at the time of the incident, visited him in jail every day and brought him food. De la Cruz’s parents sued Cedeño for a reported $100,000 in damages on behalf of de la Cruz’s 3-year-old daughter. (Cedeño was not the father.) Jim Wynn understood why Cedeño carried a gun: “I played one year over there and I think it’s a fairly common thing. I know a lot of people do it. They have so much trouble down there and a lot of it has to do with changes in the government.”23

On December 31, 1973, Magistrate Socrates Diaz Curiel reduced the charges against Cedeño to involuntary manslaughter and freed him on $10,00 bail after 20 days in jail. On January 15, 1974, Cedeño was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter. The conviction could have resulted into up to three years in prison, but Cedeño got off with only a $100 fine. A transcript of the court ruling said that Cedeño had been found responsible for acting “imprudently in allowing the victim to obtain the firearm he was carrying, and in handling it clumsily it discharged, causing her death.”24

Cedeño settled the two civil cases against him. The Astros were criticized for only being concerned about the impact on the franchise and not showing any concern for the victim. Of the tragedy, Cedeño responded, “I am sorry about what happened. But this will help me grow up faster. I think this will help me be a better person.”25 He knew there would be backlash from the opposition’s fans and players, but, “I think I can handle it. I’ve been thinking about it and I’m ready for anything. Since I’ve come into the league, they’ve yelled at me, called me hot dog. This is different, but I won’t think about it.”26 Commissioner Bowie Kuhn did not suspend Cedeño, though he had the power to do so; he did not even comment on the matter.

Cedeño got off to a hot start in the 1974 season. By the All-Star break he was leading the National League in RBIs (75), second in home runs (19), third in stolen bases (36), tied for third in runs scored (62), and tied for fourth in hits (112).27Perhaps because of backlash by fans, Cedeño was not elected a starter in the All-Star Game but was chosen as a reserve. He did not place in the top six National League outfielders in the fan voting.28 On July 17, there was a reminder of the offseason incident when teammate Bob Watson was awakened by a phone call in his Pittsburgh hotel room. A Latino-sounding voice said, “I’m going to shoot Cedeño just like he shot that girl.”29 A shaken-up Watson informed his manager and police were present that evening at Three Rivers Stadium as a precaution. The phone call occurred a day after a newspaper article criticized Cedeño’s role in the fatal incident. Manager Preston Gomez told Cedeño, “This is something that you will have to live with the rest of your life.”30

Cedeño went into a slump from August until the end of the season (.194, four home runs), which he blamed on a “bad loop” in his swing. For the season, Cedeno struck out a career-high 103 times and his batting average (.269) was his second worst. Despite the second-half swoon, Cedeño achieved career highs in home runs (26) and RBIs (102). It was his third straight season with more than 20 home runs and 50 stolen bases. At age 23, the young Dominican was still considered a budding superstar. The impact of the offseason tragedy and workload weighed on Cedeño. “I went through a lot of problems with the fans and such. I had a lot of people against me and it made it a little tougher to do my job. … I haven’t played that many games (160) since 1971. I think I can help the club more if I play 150 games and rest maybe 10 or 12 games.”31

Cedeño’s next three seasons, 1975-1977, were solid but for him unspectacular. He didn’t have that breakout .350, 30 home runs, 120 RBIs season that was expected. He batted between .279 and .297 and hit fewer than 20 home runs each season. Cedeño was still spectacular in the field and stole more than 50 bases for the sixth consecutive year. He was still dogged by de la Cruz’s death and by unreached potential. “No matter what I do, they think I had a bad year,” he said.32

Of the fatal incident, Cedeño had two responses: “It never affected my playing” and “I’d rather not talk about it.”33 Fans heckled him with yells like “Who are you going to kill next?”34 Rival players taunted Cedeño, calling him, “the fastest gun in the West.”35 Teammate Bob Watson thought the incident affected Cedeño. “He was so young, so proud, that I think he tried extra hard to prove to everyone that it never bothered him,” said Watson. “He had a good season [1974], but he altered his swing trying to hit homers. After that, maybe pitchers adjusted, and he hasn’t readjusted himself.”36

Cedeño’s injuries and aggressive style of play were taking its toll. He never fully recovered from injuring his right knee in winter ball in 1972 and it took him 20 to 30 minutes to get his problem ankles loose every day. In spring training in 1977 Cedeño tore ligaments in his finger when he ducked out of the way of a pitch thrown by a pitching machine. “He certainly never dogs it,” said manager Bill Virdon. “In fact, I guess you could say he plays with reckless abandon.”37

Cedeño hit a low point on June 22, 1977. He had gone 0-for-5 in a game in Montreal and 0-for-20 to lower his batting average to .179, and asked Virdon to take him out of the lineup. After a few days off, Cedeño was back in the lineup and batted .349 the rest of the season to raise his average to .279.

Cedeño was eligible for free agency after the 1978 season. The Astros did not want to lose their 27-year-old star and signed him to a record 10-year, $3.5 million contract.

On June 16, 1979, in the bottom of the fifth inning against the Chicago Cubs in the Astrodome, Cedeño tore the medial collateral ligament in his left knee sliding into second base while trying to take an extra base on an RBI single. The attending doctors performed two-hour surgery to repair the knee and were confident that Cedeño would play again. Dr. Harold Brelsford noted, “When we examined the knee under general anesthesia, we found previous ligament damage and were able to repair that, too. César has had trouble with that knee before. And it could be that next year his knee will be stronger than it was this year.”38 Cedeño was in a cast for six weeks and then had six weeks of rehab. He played in the last two games of the season.

Cedeño’s daily offseason regimen included a two-mile run, 30 minutes of baseball running sprints, and a session with Nautilus weights. He was confident of a full recovery. “Some people have predicted I will lose three or four steps, I will prove them wrong,” he said. “I think my best years are in the future. … I don’t think I’ve been physically sound for four years. I’ve had four operations, three on my hands. … Some people don’t realize that I have been taking shots for the past five years because I was having pains in my leg. Hopefully I won’t ever have to complain again.”39

The Astros were contenders in the NL West in 1979 and with the emergence of rookie Jeffrey Leonard, along with Jose Cruz and Terry Puhl, they had an abundance of outfielders. Cedeño, the five-time center-field Gold Glove winner, was moved to first base. He said, “Don’t forget, I was signed as a first baseman and played more than 200 games at first base in the minors. I have always taken infield practice.”40 He played in 91 games at first base in 1979 and played well, but he was not the Cedeño of old. He was slowed down by the recovery from MCL surgery and was hospitalized for a week in August with hepatitis. Cedeño finished the season batting .262 and a then-career-low .374 slugging percentage.

In 1980, at age 29, Cedeño reclaimed his starting center-field position and had one of his best seasons. He tied for fourth in the National League in batting with a .309 average, and had 48 stolen bases and a career-high .389 on-base percentage. The Astros led the Los Angeles Dodgers by three games with the final three in Dodger Stadium. The Dodgers won all three to force a one-game tiebreaker. The Astros prevailed and won their first National League West title.

The Astros met the Philadelphia Phillies in the NLCS. Game Three was the first playoff game in Astrodome history. In the sixth inning Cedeño grounded into a double play, stepped on first base awkwardly and fractured his right ankle, ending his season. The Astros won the game in extra innings, 1-0, and took a two-games-to-one lead. The Astros had the Phillies on the brink of elimination in Games Four and Five, but the Phillies came back to win both in extra innings and take the series. Cedeño, meanwhile, began another lengthy rehabilitation.

In the strike-shortened 1981 split season, Cedeño played in 82 games – 45 at first base and 34 in center field. His offensive production was down: a .271 batting average with 5 home runs and 12 stolen bases.

On September 8, in a game in Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in front of only 2,800 fans, Cedeño struck out to end the first inning. He went after a fan in the stands who had been heckling him since the prior day’s game, yelling “Killer, killer, killer.” Cedeño said afterward, “If I had been alone, I probably would not have reacted that way. But my wife was with me on this trip. Cora has been subjected to the same language and treatment. She was near tears. I don’t think any man would want his wife to hear him called that. At the time I went into the stands, I was pretty much emotionally involved. I didn’t have any intention of hitting the man. I just wanted to see if he had the nerve to call me that to his face. He didn’t. He was shaking.”41 Cedeño was fined $5,000, but was not suspended. The fan was ejected from the ballpark. Cedeño’s agent argued for a policy to deal with abusive fans. No charges were pressed against either Cedeño or the fan.

The Astros won the second-half National League title and lost to the Dodgers inn five games in the Division Series. Cedeño batted only .214 in the series and did not play in the deciding game.

In the offseason, Cedeño, a player with trade-veto rights, approved a trade to the Cincinnati Reds for Ray Knight, a player he fought with during the 1979 season. A happy Cedeño said, “I believe I’ll benefit from a change of scenery and believe my best years are still ahead of me.”42 The Reds planned to play him in center field after trading Ken Griffey Sr. earlier in the offseason, which pleased Cedeño, who grew reluctant to move from that position under Virdon. He felt his broken ankle was healed, saying, “During the past season, I played with only 17 percent flexibility in my ankle, and favoring the ankle caused me to have hamstring and back problems.”43 After a month of offseason rehab, Cedeño reported, “Already it’s up to 80 percent flexibility, I’m ready to steal 50 bases for the Reds this season.”44 It was reported that Cedeño had a stormy relationship with Virdon and accused the club of not giving him enough time to recover from some of his injuries.45 Houston teammates took jabs at Cedeño, claiming that he didn’t play while hurt and left more than his share of runners on base.

In the offseason, Cedeño, a player with trade-veto rights, approved a trade to the Cincinnati Reds for Ray Knight, a player he fought with during the 1979 season. A happy Cedeño said, “I believe I’ll benefit from a change of scenery and believe my best years are still ahead of me.”42 The Reds planned to play him in center field after trading Ken Griffey Sr. earlier in the offseason, which pleased Cedeño, who grew reluctant to move from that position under Virdon. He felt his broken ankle was healed, saying, “During the past season, I played with only 17 percent flexibility in my ankle, and favoring the ankle caused me to have hamstring and back problems.”43 After a month of offseason rehab, Cedeño reported, “Already it’s up to 80 percent flexibility, I’m ready to steal 50 bases for the Reds this season.”44 It was reported that Cedeño had a stormy relationship with Virdon and accused the club of not giving him enough time to recover from some of his injuries.45 Houston teammates took jabs at Cedeño, claiming that he didn’t play while hurt and left more than his share of runners on base.

In his three-plus seasons in Cincinnati, Cedeño stole only 57 bases, hit 30 home runs and batted .265. In 1983 he was moved to right field. In 1984 he played a utility role, splitting time at first base and all three outfield positions.

In August 1985 Cedeño was being used primarily as a pinch-hitter and was batting under .250. On the 27th St. Louis Cardinals lost their right-handed slugger, Jack Clark, to the disabled list. The Cardinals held a three-game lead in the National League East over the New York Mets, and Clark was one of their few players who could deliver a big hit. Cedeño was unhappy with his part-time role in Cincinnati, telling sportswriters, “I accepted the fact that I wasn’t going to play much, but I don’t think you would like it if they didn’t let you write all the time either.”46 While the Cardinals were in town on August 28, Reds coach Jim Kaat suggested to manager Whitey Herzog that the Cardinals acquire Cedeño. A deal was struck the next day for the 34-year-old Cedeño in exchange for rookie-league outfielder Mark Jackson. Jackson never played above Class-A.

Cardinals general manager Dal Maxvill said, “Our thinking is (Cedeño) can help us in the stretch run. He is not going to be playing a great deal unless we have injuries, but it’s nice to have someone on your bench that makes managers do something they may not want to do.”47 Cedeño was happy for the opportunity. “It’s no secret that my contract is up in five or six weeks and there is no doubt in my mind that I can still be a regular player for somebody,” he said. “I am happy to have an opportunity like this – to play with a contender – came around. I welcome whatever they want me to do. I’m thrilled an organization like the Cardinals had interest in me. It’s a great feeling to be wanted.”48

Cedeno platooned at first base with veteran Mike Jorgensen and pinch-hit. On August 30 against the Astros, in his first appearance for the Cardinals, he hit a pinch-hit home run on the first pitch to him by Mike Scott. On September 6, Cedeno pinch-hit for Jorgensen and hit a grand slam off the Braves’ Gene Garber to secure an 8-0 victory. Later the Cardinals and Mets, tied for first, squared off in a three-game series in Shea Stadium. The Mets took two of the three games. In the second game, Cedeño led off the 10th inning with a home run off Jesse Orosco that was the difference in a 1-0 game. The Cardinals left New York one game behind the Mets and Cedeño became the starting first baseman until Jack Clark returned. On September 15 against the Cubs, Cedeño went 5-for-5 with the game-winning hit, a home run in the seventh. In the division-clinching game, a 7-1 victory over the Cubs on October 5, Cedeño helped break open a tight game with a home run and two RBIs.

In 28 games, Cedeño batted .434 with 6 home runs, 19 RBIs, and a .750 slugging percentage. Herzog said, “If we hadn’t got Cedeño, we would have been at least three games out of first, maybe more, going into this last week. If we didn’t have him, a few lefties may have stopped us and that may have sent us into a slump. But he didn’t let our morale go down.”49Said Cedeño, “I always believed in my own ability. I knew I could still play and was trying to prove I could. I think I did. It was one of the most exciting months of my life.”50

The Cardinals defeated the Dodgers in the NLCS. In Game One of the World Series, against Kansas City, Cedeño doubled in the decisive run in the top of the fourth inning. As the Cardinals lost to the Royals in seven games, Cedeño played in five games and batted .133. Overall, in four postseason series, Cedeno played in 17 games, hitting .173 in 52 at-bats.

After the season Cedeño was a free agent and signed with the Toronto Blue Jays. After hitting .188 in nine exhibition games, he was released on April 3. But the Dodgers were in need of help after Pedro Guerrero suffered a knee injury and signed Cedeño to a one-year contract. He played in 37 games for the Dodgers, batting .231, and was released in early June. Cedeño finished out the season with Louisville, the Cardinals Triple-A affiliate.

Cedeño played in the Mexican League in 1988. In 1989, at the age of 38, he was invited to the Astros spring training as a nonroster player. He was released on March 28, closing the books on his major-league career. Later that year, Cedeno played in the inaugural season of the Senior Professional Baseball Association.

Cedeño had a temper that he could not control at times. A Houston reporter who regularly covered the team said, “César has a very bad temper. When he is going good, he can be the most cooperative guy around. But if he’s going bad, or has an injury, then he’s a difficult to get along with.”51 Cedeño racked up fines and suspensions not already noted because of his temper. In 1971 he threw his helmet after striking out and accidentally hit teammate Wade Blasingame. The two argued, teammate Doug Rader joined in, and he and Cedeño started shoving each other. In 1972 Cedeno was fined $250 and suspended for three games for bumping umpire Frank Pulli. During spring training in 1975, Cedeño was fined $200 for smashing a glass water cooler after he popped out to the shortstop in an exhibition game in which he also homered and doubled. A piece of glass was lodged in a teammate’s eye, but it was easily removed by the team doctor. During the 1975 season Cedeño was fined $250 and suspended for three games for bumping umpire Bruce Froemming. In 1978 he was fined $5,000 for injuring himself when he punched the plexiglass dugout roof, injuring his hand and requiring 17 stitches. In 1983 Cedeño was fined $100 and suspended for three days when he threw a temper tantrum because he was not selected by the manager to fly first class.

In the offseason Cedeño received treatment for stress management. He also had a history of off-field episodes. In 1985 he was charged with drunk driving when, after his car struck a tree, he refused to take a breath test, paid a $400 fine and $7,000 for property damage. Cedeño was put on probation. In 1987 he was charged with smashing a glass in a man’s face in a Houston area nightclub after the man accidentally bumped into him. In 1988 Cedeño was arrested and charged with assault causing bodily injury and resisting arrest. The woman Cedeño had beaten was his girlfriend, Pam Lamon, with whom he had a four-month-old daughter. Cedeño was drunk and angry about custody of the child, took the child from Lamon and drove off. He was still married to Cora at the time. In 1992 Cedeño was arrested for assaulting Lamon who was four months pregnant with his child. He was also charged with resisting arrest. Lamon’s victim’s statement read, “Cesar has a serious drinking problem and only becomes abusive when he drinks. I have begged him to get help, but he won’t.”52

Cedeño was a minor-league coach and hitting instructor for the Astros from 1990 to 1994 and 1997 to 2001. He was a coach in the Washington Nationals organization in 2009. In 2012 he returned to the Astros as the hitting coach for the Greenville Astros of the Appalachian League. In 2018 Cedeno was the hitting coach for the Astros team in the rookie Gulf Coast League.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted articles in The Sporting News as well as Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame clipping file.

Notes

1 Ron Fimrite, “Now Let Us Render Unto Cesar,” Sports Illustrated, May 21, 1973, si.com/vault/1973/05/21/618333/now-let-us-render-unto-cesar, accessed November 17, 2018.

2 Lou Brock was the first in 1967. Cedeño accomplished this feat three times, second behind Rickey Henderson, who did it four times. Cedeño is the only player to have three consecutive seasons of 20 home runs and 50 stolen base as of 2018.

3 Bob Moskowitz, “Teen-Ager Cedeno a Terror at Bat,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1969: 49.

4 John Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Super Star,” The Sporting News, August 19, 1972: 3.

5 John Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Super Star.”

6 Harold Petersen, “Hail, Cesar! And Hello,” Sports Illustrated, August 2, 1972, si.com/vault/1972/08/07/614021/hail-cesar-and-hello, accessed November 23, 2018.

7 Petersen.

8 Bob Dellinger, “Astros Hail 89ers Cesar as Minors’ Top Prospect,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1970: 33.

9 John Wilson, “Cedeno Dances While the Astros Fiddle,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1970: 15.

10 Wilson, “Cedeno Dances While the Astros Fiddle.”

11 John Wilson, “Astros’ Cedeno Earns New Chance With a Hot Bat,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1971: 12.

12 On August 31 Cedeño led Williams.342 to .340. Both were batting .340 on September 1. Williams passed Cedeño on September 2 and led him the remainder of the season.

13 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

14 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

15 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

16 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

17 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

18 Wilson, “Cesar Cedeno … The Next Superstar?”

19 Joe Heiling, “Faded Astros Face Pruning Job from Fed-Up G.M. Richardson,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1973: 17.

20 “Prosecutor Recommends Cedeno’s Full Acquittal,” New York Times, January 15, 1974: 44.

21 “Cedeno Expects Reaction,” New York Times, January 23, 1974: 25.

22 Joe Heiling, “Cedeno Tragedy Tosses a Cloud Over Astros,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1973: 27.

23 Heiling, “Cedeno Tragedy Tosses a Cloud Over Astros.”

24 “Cedeno Expects Reaction.”

25 Joe Heiling, “Cesar Set for Brickbats: ‘I May Be a Better Player,’” The Sporting News, February 9, 1974: 33.

26 Heiling, “Cesar Set for Brickbats: ‘I May Be a Better Player’.”

27 Larry Wigge, “Batting Averages, Including Games of July 24,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1974: 39.

28 “Dodgers, Reds Place Three on Major All-Star Team,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1974: 11.

29 Joe Heiling, “Cedeno’s Life Periled by Pittsburg Caller,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1974: 7.

30 Heiling, “Cedeno’s Life Periled by Pittsburg Caller.”

31 Joe Heiling, “Cedeno Aims to Be Astros’ Leader,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1974: 25.

32 Peter Gammons, “Cesar’s Salad Days Are Over/Supposed Superstar Cedeno of Houston Is Playing More Like a ‘Could Have Been,’” Sports Illustrated, August 1, 1977.

33 Gammons.

34 Gammons.

35 Gammons.

36 Gammons.

37 Gammons.

38 Harry Shattuck, “Cedeno’s Knee Injury Gives Astros Another Limp,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1978: 16.

39 Harry Shattuck, “ ‘Best Years Ahead’ Trumpets Cesar of Astros,” The Sporting News, March 10, 1979: 51.

40 Harry Shattuck, “Leonard Gets Help as Astros’ Rookie Star,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1979: 10. According to baseball-reference.com, the only minor-league games in which Cedeño played first base are the 97 games he played in 1969 between Peninsula Astros and Florida Instructional League Astros.

41 Harry Shattuck, “Cedeno Is Fined. Goes After Fan,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1981: 23.

42 Earl Lawson, “Reds to Put Cedeno in Center Field, Ankle Healed,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1982: 40.

43 Lawson.

44 Lawson.

45 Harry Shattuck, “Astros Very Cool to Scott Pay Bid,” The Sporting News, January 9, 1982: 45.

46 Rick Hummel, “Price Is Right in Cedeno Deal,” The Sporting News, September 16, 1985: 19.

47 Hummel.

48 Hummel.

49 Dave Nightingale, “Races to the Wire, Herzog Played His Cards Right Down the Stretch,” The Sporting News, October 14, 1985: 17.

50 Jared Hoffman, “What a Move, When the Cardinals Acquired Aging Cesar Cedeno for ’85 Stretch Run, They Found the Ultimate Difference-Maker,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1997: 47.

51 Abby Mendelson, “Whatever Happened to Cesar Cedeno?,” Baseball Quarterly, Winter 1978-1979: 46.

52 Henry Pierson, “Ex-Astro Charged With Attack on Pregnant Girlfriend, Cops,” Orlando Sentinel, September 29, 1992. articles.orlandosentinel.com/1992-09-29/news/9209290123_1_astros-cedeno-pregnant-girlfriend, accessed on November 23, 2018.

Full Name

César Cedeño Encarnación

Born

February 25, 1951 at Santo Domingo, Distrito Nacional (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.