Joseph J. Lannin

Joseph J. Lannin owned the Boston Red Sox for less than four full years, but in that short span, the team won two world championships in the back-to-back years 1915 and 1916.

Joseph J. Lannin owned the Boston Red Sox for less than four full years, but in that short span, the team won two world championships in the back-to-back years 1915 and 1916.

A native of the Province of Quebec, he came to the United States at a very young age – the story says he was orphaned and walked all the way to Boston. He became a remarkably successful businessman. This Canadian from rural Quebec became the team owner responsible for bringing Babe Ruth to the Red Sox. Lannin departed life plunging from the ninth story of a hotel he owned in Brooklyn, New York.

Lannin was a dedicated baseball fan. When he first made a splash in the Boston newspapers, it was with his purchase of a significant share of the Red Sox, announced in the newspapers of December 1, 1913. He did at the time own a portion of Boston’s other major-league ballclub, the National League’s Boston Braves. He had tried to buy the Braves outright but that offer had been declined.1

John I. Taylor of the Red Sox had sold half of the club on September 15, 1911, to James McAleer, manager of the Washington Senators, and Robert McRoy, who was secretary to American League President Ban Johnson. It was, say Red Sox historians Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, “no secret that McAleer was only the front man in the deal. Most of the money was Johnson’s.”2

For his part, Taylor became vice president but was not actively engaged in running the ballclub. His eyes were on real estate and he used the income from the sale to help fund his Fenway Realty Company, which purchased the land on which he built Fenway Park in time to open on April 20, 1912. That very year, the Red Sox won the World Series.

During 1913, however, there was competition brewing in the form of the Federal League – which did indeed “raid the rosters” of both established major leagues and fielded teams in both 1914 and 1915. As it became clear that the Federal League was becoming a reality, and a threat, Ban Johnson moved to bring in someone else – someone he perceived as more pliable, but someone who had money, too. He turned to Lannin and his Lannin Realty Company, which purchased the shares owned by McAleer and McRoy. The Boston Globe noted, “The change in ownership has the sanction of Pres. Johnson of the American League, who had a prominent part in the negotiations, which will be closed at an early date.”3

Lannin couldn’t own 50 percent of the Red Sox and retain a minority stake in the Braves. Braves owner James E. Gaffney declared, “Lannin will sell his stock in my club and will resign from the board of directors.” He said he was sorry to see Lannin leave, that he thought he was the “right man” to take over from McAleer et. al., adding that he “has plenty of money and is a baseball fan of the 33rd degree.”4

The Globe story added about Lannin, “Mr. Lannin is a large real estate owner in New York, as well as in this city. He owns Arborway Court, Jamaica Plain, and many large apartment houses in Greater Boston. Mr. Lannin is a baseball enthusiast.”5

At the time, Lannin was a resident of Hyde Park, New York. He had only become a member of the five-person board of directors of the National League ballclub in November.6 The Boston Herald characterized him as a “Boston man” in its headline on its front-page story about his buying into the Red Sox, but noted him as “of Boston and New York.” The forced sale of the Red Sox stock was said to be “the direct outcome of the ‘royal rooters’ episode of the world’s series of 1912.”7

The amount Lannin invested was reported as $220,000 for half of the shares of the Red Sox, acquiring those held by McAleer, McRoy, and Garland “Jake” Stahl. General Charles H. Taylor and his son John I. Taylor had sold the shares to McAleer et al. for $170,000 in the winter of 1911-12. The Red Sox beat the New York Giants to win the 1912 World Series and were said to have turned a profit of $400,000. However, management had blundered badly before Game Seven. The long-standing booster club, the Royal Rooters, paraded onto the field prepared to take the several hundred seats that had always been reserved for them, only to learn that “in a huge miscalculation, team treasurer Robert McRoy made the Rooters’ tickets available to the general public.”8 The Rooters pretty much boycotted the final game of the Series, leaving the park only half-full; with the Series tied at three wins each, attendance for the clinching game dropped from 32,694 to just 17,034. Boston Mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald was an active Rooter and had gone with the group to the games in New York. He called for McRoy to be removed from his position.9

The Taylors wanted to buy back the shares they had previously sold and become 100 percent owners of the ballclub, but Ban Johnson steered the sale to Lannin.10

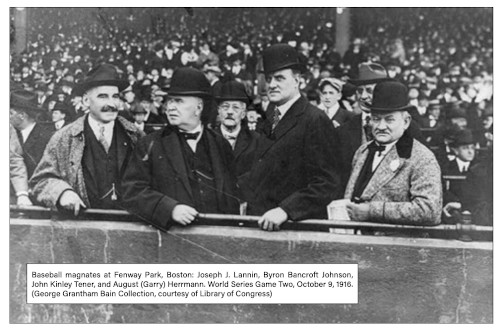

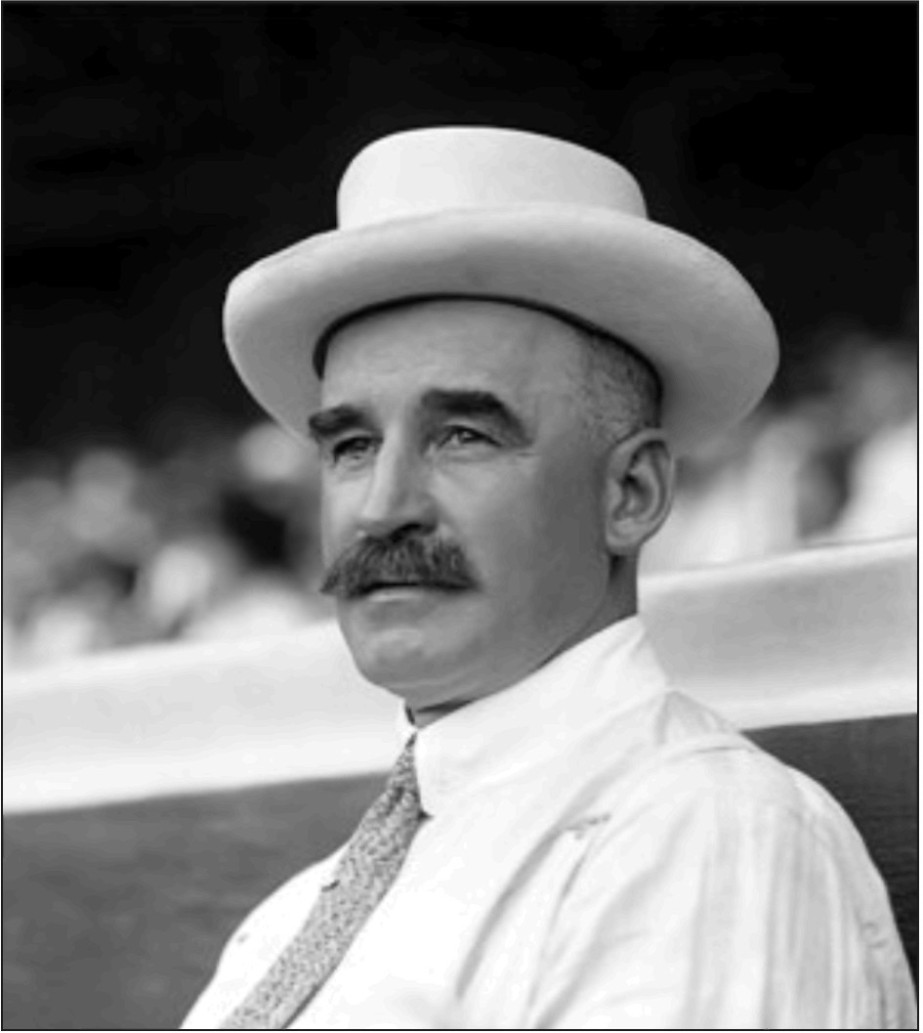

Joseph J. Lannin, December, 1913 (Bain News Service, courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Joseph John Lannin was born in Lac-Beauport, a town about 15 miles north of Quebec City. Officially known as Saint-Dunstan-du-Lac-Beauport, the town was a municipalité de paroisse in the region Le Jacques Cartier; it was renamed simply as Lac-Beauport in 1989.

His father, John, was a farmer, born in Skull, County Cork, Ireland, in 1814, who had emigrated to Canada. John had lost his first wife and mother of four at St. Dunstan in 1846 and married Catherine Evers, likewise an Irish immigrant, in 1847. Catherine was mother to nine more children, one of whom died in infancy. Joseph was the next-to-last child to join the Lannin family. He was born at Lac Beauport on April 23, 1866.

John Lannin died on September 6, 1869.11 Though it is unclear from records consulted, the family perhaps continued to farm. Joseph was only three years old at the time of his father’s death. His half-sisters, Mary and Ann, and half-brother, William, were all in their mid-20s or early 30s, and his older brother, Thomas, was 16.

Catherine Lannin remarried in 1874, but died on December 1, 1880. Joseph was orphaned at age 14. He took a job working as a bellhop at the St. Louis hotel in Quebec and came to know some of the clients who used the hotel.12 He then made his way to Boston. His great-grandson researched the journey as best he could and says, “J.J. walked many segments during his route to Boston, taking odd jobs along the way to rest and earn money, and it is believed that he also rode some trains along the fur route during his journey.”13 A profile in the Boston Globe said he “knew several Boston men who went to Quebec and Montréal to buy fur garments, and when he came to Boston [in September 1881] it was to begin as office boy in a store to which he was recommended by one of these friends.”14

Lannin soon found another position, working as a bellhop at Boston’s Parker House for a year, and then the new Adams House.15 He was apparently a diligent worker, and personable, and worked his way up to head bellboy and was then put in charge of one of the watches. He became a waiter, and then headwaiter. One of the men he had gotten to know over a couple of years told him of a position at the new Charlesgate Hotel and he became steward and “in a short time he became manager.”16

Lannin became a naturalized United States citizen on October 19, 1887. The formal paperwork said he had arrived in Boston “on or about the third day of September in 1881.” He was, the document stated, “an Alien and a free white person.” He was working in a cigar business at the time. In signing the form, he forswore “any allegiance and fidelity to every foreign Prince, State, Potentate, and Sovereignty whatsoever – more especially to Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom and Ireland, who subject he had heretofore been.”17

Lannin had married Hannah J. Furlong in Boston on November 29, 1890. He was listed as a waiter at the time; she was a milliner, hailing from Montréal.

He was ambitious, and even at a young age made an early investment in real estate in the Forest Hills section of Boston, as well as beginning to take a two-year course in business at a local business school, studying in his spare time.

He was apparently also proficient in playing lacrosse, playing with the championship South Boston Lacrosse Club, and became a fan of baseball.18

After four years at the Charlesgate, Lannin came to learn of an opportunity out of state and leased a hotel at Lakewood, New Jersey, and then the Garden City Hotel on New York’s Long Island; the Globe article said he was “backed by friends who had great confidence in his ability.” He became proprietor of the hotel at Garden City, and was also brought into ownership of the Great Northern Hotel in New York. The former bellhop had now “entered the road toward wealth.”19 He came to own a couple of apartment buildings in Forest Hills and had a number of other real estate investments in New York.

An 1889 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer suggested some of the circles into which Lannin had entered, citing him as a partner with Willard D. Rockefeller in New Jersey’s Allenhurst Inn.20

In 1903 the Boston Herald showed him opening the Summit Spring Hotel resort in Poland, Maine.21

Lannin was very interested in competitive checkers as well as lacrosse and baseball, and in 1905 greeted a group of 10 British checkers masters who had come to New York on their way to Boston for an international match.22

He maintained his legal residence in Boston, at least through the time of the 1910 census.23

It 1912 Lannin purchased a number of shares in Boston’s National League club, the Braves. Team vice president C. James Connelly had known him “since almost the first day he put in an appearance as a bellboy at the Adams House.” Connelly said Lannin “was popular with everyone from his first day on the job … and as a youngster showed the same care for detail and thoroughness in everything he did that since has served to bring him so great a success in his chosen calling.”24

The naming of Lannin as president of the Boston Red Sox was formalized on December 24, 1913, at the team’s offices in downtown Boston.25

Lannin said he had been asked, “Why did I wish to be the president of a baseball club?” He simply said, with a laugh, “Well, because I was such a darned fan.”26 He later said, “I have wanted to own a baseball club ever since I was a bellboy in Boston, I used to sneak into the games then every chance I got, and if one of the players let me carry his bat I was the happiest little Irish kid in all Boston.”27

In 1914 the Red Sox finished in second place in the American League. They had been world champions in 1912, then dropped to fourth place with a record of 79-71 in 1913, finishing 15½ games behind the Philadelphia Athletics.

The shares of the Braves that Lannin had owned were placed with Gaffney and before year’s end were sold to C.J. Connelly.

The Federal League launched as a third major league and fielded competitive teams in both 1914 and 1915, inducing a number of players to jump their contracts with American League and National League clubs, while driving up salaries for the better players because of the entry of a third competitor.28 Lannin professed not to be worried about the Federal League and foresaw a stronger season for the Red Sox in 1914.29 Rather, there was some talk that the Red Sox were so well supplied with talented ballplayers that they might let a couple of them go to the New York Yankees.30

On March 6 Tris Speaker signed a two-year deal with the Red Sox for what was thought to be $18,000 a year – more than had ever been paid any player to that date. He reportedly had turned down an offer for $60,000 from the Federal League. Lannin declared, “Baseball is an exciting sport for a new beginner. We had to give Speaker the money, but he is worth it.”31 Speaker’s signing resulted in enthusiastic support from Boston baseball backers.32

Lannin joined the team for 1914 spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas. On May 11 at Hot Springs, he announced another two-year deal, this one for left-hander Ray Collins.33 Both Collins and Speaker excelled for the Red Sox in 1914.

On May 14 Lannin bought all the common stock shares that the Taylors owned and became the sole owner of the Red Sox.34 Though he had many real estate ventures in New York, Lannin still reportedly had “something like a thousand tenants in the apartment houses he owns in Boston” and he “presented each rent payer with a season pass to the games played by the Red Sox.”35

Lannin was said not to smoke, drink, or chew tobacco, and he said he wasn’t one for sequestering himself in a box seat at a game. “I should say not. I like to get out among the real fans and hear what the supporters of the game think about my team. Some days I go out in the bleachers and sit among those who know all the players by their first names.”36

He enthused about how thrilled he had been to see the Red Sox win the World Series in 1912 and how disappointed he had been to see them fall as badly as they had in 1913. At the end of July 1914, he said, “I have been traveling with the Red Sox all season and I have enjoyed it immensely. I like to fraternize with the players, with whom it is a pleasure to talk over the games after they are played. Any real baseball fan probably would like to know his favorite players personally, and I always remember than I am as much a fan as anybody.”37 He said he had never – and would never – interfere with his manager.

On July 14 it was announced that Lannin had purchased the contracts of two pitchers named Ruth and Shore from Baltimore’s International League ballclub, as well as a catcher named Ben Egan, for a price he said was more than $25,000.38

At the end of the month, he purchased the International League’s Providence Grays baseball team as well as its grounds, not for his own sake but in order to help the fight against the Federal League.39

On August 4 Lannin offered the Boston Braves free use of Fenway Park for Saturday games and on holidays.40 (The South End Grounds, where the Braves played, had half the capacity of Fenway Park.) After August 11, the Braves played every one of their remaining 27 home games at Fenway Park. and they played all the home games of the 1914 World Series in Fenway Park. Brand-new Braves Field opened in April 1915.41

Catcher Bill Carrigan was player-manager of the Red Sox; he had taken over from Jake Stahl midway through the 1913 season. The 1914 team struggled in the first half of the season, often in the second division, but on July 22 reached second place and never relinquished that position. Ray Collins and Dutch Leonard were the team’s best pitchers. Leading the team in all three categories, center fielder Tris Speaker had a .338 batting average, four home runs, and 90 runs batted in. His 287 total bases led the league. At the last game of the season, Lannin announced that he had signed Carrigan to a new contract covering the 1915 and 1916 seasons.42

The Red Sox had improved to 91-62, but the Philadelphia Athletics won 99 games. The Boston Braves won the National League pennant, having gone in two years from last place in 1912 to the pennant. The so-called Miracle Braves won the World Series from the Athletics.43

After the season was over, the Federal League made overtures toward peace but Lannin – now a significant force in American League circles – wasn’t having any of it.44 That was his public stance, but he was later said to have held talks behind the scenes in a number of clandestine meetings.45 The story was later dubbed a “yarn.”46

In a post-Christmas message, Lannin wrote an article for the Boston Herald predicting that the Red Sox would win the pennant in 1915.47

The Federal League kicked off 1915 with a lawsuit against Lannin and the other magnates of the two more established leagues. Lannin said it appeared that the upstart league was upset because some of its players were wanting to jump back to the American and National Leagues. In a public pronouncement on being served papers to appear in court, he voiced an argument that began, “Baseball is not commerce. …” The argument perhaps foreshadowed the US Supreme Court ruling in Federal Baseball Club v. National League, 259 US 200 (1922) that granted baseball an exemption from antitrust law.48 Lannin worried that the “millions of dollars” being spent in the fight with the Federal League might result in it sometime costing as much as $2 to see a major-league baseball game.49

As the 1915 season began, Lannin selected the location at Fenway Park from which the Braves could fly their two pennants – the National League and World Championship flags.50 The team played all its home games at Fenway Park until August 18, when the new Braves Field opened its gates and hosted its first Braves game.

Lannin was optimistic before the 1915 season began, but expressed concern that all the nice things being said about the Red Sox might result in the players becoming “too sure of winning” and undercut their play on the field.51

On March 4 Lannin boarded the train at Boston’s South Station and headed for spring training again in Hot Springs. Once more he traveled with the team throughout the season, though not to every game. Interestingly, a “movie man” traveled with the Red Sox filming the team. A news story explained, “Lannin will use the pictures in movie theaters in and around Boston during the winter. They will illustrate baseball talks. The pictures will show the Sox on every American league playing field.”52

The Red Sox had perhaps the highest payroll in baseball, as the team featured a number of standout players. It had no 20-game winner on the pitching staff but had five starters who each won 15 or more games and a team ERA of 2.39. Rube Foster was 19-8. The two pitchers Lannin had purchased from Baltimore excelled – Ernie Shore was 19-8 and Babe Ruth was 18-8. Dutch Leonard and Smoky Joe Wood each won 15. There was a more balanced offense, too. Speaker once more led in batting average (.322), but Duffy Lewis drove in 76 runs, seven more than Speaker.

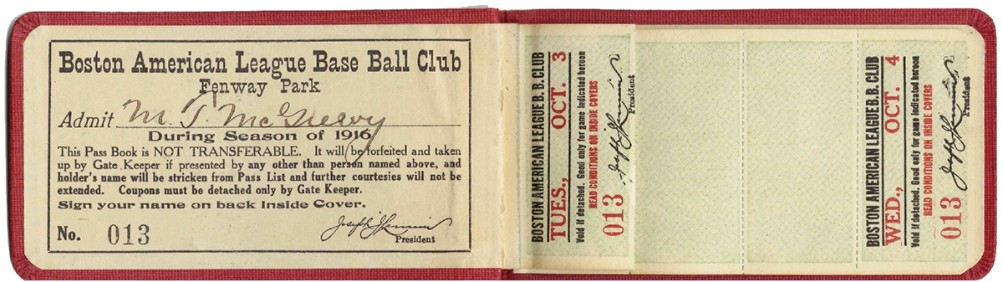

“Nuf Ced” McGreevy’s season pass to Fenway Park for the 1916 Boston Red Sox season. (Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevy Collection, Boston Public Library)

And the leading home-run hitter on the team was its 20-year-old pitcher, Ruth.

It wasn’t as though it was smooth sailing all year. Dutch Leonard was suspended for a couple of months for undermining the authority of Bill Carrigan.53 There were personnel changes; Lannin purchased the contract of Jack Barry in July. The team finished May in fourth place, but finished June in second. The Red Sox attained first place on July 19 and – save for August 19-20 – remained there for the remainder of the season. It was a tight race and they finished with 101 wins, just one more than the Detroit Tigers.54

On September 22 Braves President Gaffney extended the same courtesy that Lannin had previously provided to the Braves: the use of Braves Field for any World Series games, should the Red Sox win the pennant.55 There was a brief brouhaha when there was word that the NL champion Philadelphia Phillies might not set aside 400 seats for Boston’s Royal Rooters. Lannin declared that he might not permit the Red Sox to play in the World Series if the team’s most fervent fans were denied attendance.56

The Red Sox lost the first game of the Series but then won the next four, every one of the wins by just one run. Games Two, Three, and Four were all 2-1 wins. Rube Foster was 2-0. Babe Ruth never pitched. His only appearance was in Game One, when he pinch-hit for Shore and grounded out to first base unassisted.

A planned transcontinental postseason tour that would have taken both teams to California was canceled by Lannin when the Phillies said they needed instead to go to a banquet in Philadelphia.57

By mid-December, Lannin had re-signed all but two of the 1915 ballclub for the coming season.58 He was one of three American League owners on the committee to try to work out terms of a “peace agreement” with the collapsing Federal League.59

The contracts Lannin sent out for 1916 contained, in a number of instances, what were characterized as “radical reductions in salaries.”60 With the demise of the Federal League, there was not the competition there had been to drive up salaries as had been the case in 1914 and 1915. Bill Carrigan was fairly clear: “The boys will receive remuneration more in conformity with their worth before the war [with the Federal League began] than with that which has prevailed during the past two years.”61 Several signed right away.

Lannin announced a reduction in ticket prices, the top rate dropping from $1.50 to $1.00.62 He sold the Providence Grays.63 There were some comings and goings, but the notable uncertainty at Hot Springs was the status of Tris Speaker. There were already tensions on the ballclub between Protestants (like Speaker, Wood, and Gardner) and Catholics (like Duffy Lewis and Carrigan). Lannin reportedly offered Speaker only half of the salary he’d been paid in the two prior years.64 Speaker held out, and Lannin traded him to the Cleveland Indians, getting Sad Sam Jones, Fred Thomas, and $55,000 in cash.65 Stout and Johnson assert that Ban Johnson had an interest in building up the Cleveland club and that there was “some evidence Lannin was coerced into making the trade, for soon relations between the two cooled dramatically.”66

Season pass to the 1916 Boston Red Sox season. (Michael T. “Nuf Ced” McGreevy Collection, Boston Public Library)

Joe Wood refused to take a pay cut and sat out the whole season, despite the personal involvement of Lannin in talks. There were even reports that Wood had offered Lannin $10,000 to let him out of his contract.67 In February 1917, Wood’s contract was sold to Cleveland.

The 1916 Red Sox won the pennant again and won the World Series again, too. They won 10 fewer regular-season games than in 1915, but topped the White Sox by two games and the Tigers by four. They started the season well, struggled in May and June and even opened July in fifth place, but then righted their ship with a 20-10 month of July, closing the month in first place. They held steady through the end of the season.

Speaker was gone.68 Larry Gardners .308 average placed him first on the team, as did his 62 RBIs. Three players each hit three home runs, enough to lead the team: Tillie Walker, Del Gainer, and Babe Ruth. Not one Red Sox player homered at Fenway Park all season long.

Ruth led the pitchers both in wins (he was 23-12) and ERA (1.75). Dutch Leonard and Carl Mays each won 18. Shore won 16 and Foster 14.

It was again a five-game World Series, this time beating the Brooklyn Robins. For the third year in a row, a Boston baseball team won the World Series – playing in a ballpark that was not their home park. The Red Sox, once again, played Series home games at Braves Field.69

Shore was 2-0 in the Series, with Ruth and Leonard each winning a game. Gardner’s six RBIs were triple those of any teammate. He hit the only two home runs for Boston. Ruth was 0-for-5, still without a hit in his postseason career. He drove in one run with a groundout in the third inning of Game Two, the only run of the game until a walk, sacrifice, and Del Gainer’s single won the 2-1 game in the bottom of the 14th inning, a complete-game win for Ruth.70

The business of baseball was definitely not as enjoyable for Lannin as it had been. He had also begun to clash with Ban Johnson. Just a couple of years later, the Atlanta Constitution wrote that a clever businessman like Lannin “could not understand why the league owners permitted Ban Johnson to pursue the tactics of a czar.” Lannin became restless. “Several clashes with Johnson were the potent factor that drove Lannin to look for a way out of the national game.”71 Perhaps he may have only served Ban Johnson’s purposes for a period of time, becoming less pliable once McAleer and McRoy were gone and the Federal League threat was over. In any event, Mike Lynch writes, “Despite the success, Lannin wanted out. He was tiring of Johnson’s meddlesome ways, and his health was beginning to fail.”72

Less than three weeks after winning back-to-back World Series, Lannin sold the team. He had “tired of [Ban] Johnson’s constant interference. … Not even a world championship offset Lannin’s growing dismay. … He realized that the rules for doing business were different if your name was Mack or Comiskey. Besides, Lannin had heart trouble.”73 It is possible that doctors urged him to give up his interests in baseball. He told the newspapers, “I am too much of a fan to own a ball club.”74

Lannin acted quickly. “Before Johnson could interfere and attempt to bring in an owner of his liking, Lannin sold the Red Sox to Harry Frazee and Hugh Ward, both of whom had made their fortunes in the theater.”75 The price was a reported $675,000. Frederick G. Lieb wrote, “Lannin caught Ban quite unawares in selling the valuable property to Frazee and Ward, and that Joe made the sale to the theatrical men knowing it would pique Johnson.”76 It was said that Lannin had made a paper profit of $400,000 on the sale.77 The sale included the grounds at Fenway Park.

Lannin still owned a controlling interest in the Buffalo Bisons, but expected to sell that, too.

Manager Bill Carrigan announced his retirement to Lewiston, Maine.

Part of the Frazee/Ward purchase was by a secured note for $262,000 to be paid later, and in 1919 the payments stopped. Lannin had to initiate legal proceedings in 1920 against the new owners. A court order was obtained to force them to sell Fenway Park and give the money to Lannin.78 Matters were, however, worked out.79 In August, he said he was going to get out of baseball altogether, selling off or breaking up his ballclub in Buffalo.80

In October 1920 Lannin sold the Buffalo team, saying he was leaving baseball “with regret” because he needed the time to attend to his “numerous hotel interests.” The New York Times averred that “Mr. Lannin was one of the big factors in the successful rebuilding of the International League, following the disastrous war with the Federal League. He furnished considerable capital to keep the league moving in the lean years following the settlement of the baseball war.”81

When Frazee sold the Red Sox to a new ownership group in July 1923, there were several who remembered the success the club had enjoyed under Lannin and hoped that new ownership could restore the team to some of its former glory. As it turns out, the new group was seriously undercapitalized, particularly so following the unexpected death in 1927 of its principal financier, Palmer Winslow. The Robert Quinn group held on for nearly a decade before selling to Tom Yawkey in early 1933.82

Lannin did stay active in competitive checkers tournaments.83 In 1924 he made headlines with his ongoing ownership of the Salisbury Country Club in Garden City, Long Island, replete with four 18-hole golf courses on over 900 acres.84 He appeared from time to time, hosting a social event in Garden City or appearing at a ballgame in Boston. Lannin also owned The Balsams, a resort hotel in Dixville Notch, New Hampshire.

The year 1927 opened with a controversy when Frank Navin, owner of the Detroit Tigers, expressed resentment concerning games back in 1916, charging that Lannin had given bonuses to pitchers on other teams who beat the White Sox, and that a number of beanballs had been thrown at Tigers players in 1917.85

One of Lannin’s properties was Roosevelt Airfield on Long Island, the field from which Charles Lindbergh took off on May 20, 1927, for his famous trans-Atlantic flight as the first aviator to fly solo and nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. Lindbergh had spent the night before at the Garden City Hotel owned by Lannin, who watched the pilot take off on his 33-hour flight to Paris.

A couple of transactions made the news in the first part of 1928. Lannin sold the Roosevelt Field runway; the land was to be made into a polo field.86 And in April he purchased the Granada Hotel, a 364-room hotel in Brooklyn, for $2,500,000.87

A few weeks later, Lannin was dead.

On May 15, he had either fallen, jumped, or was pushed out of a ninth-story window at the Granada. He had died instantly, landing on the two-story roof of a restaurant that extended off the hotel. The New York State certificate of death reports that his skull and chest were crushed. He was 62 years old. The medical examiner’s ruling was that he had fallen.

Friends said he had suffered a series of heart attacks and that – even though there was reportedly no one present in the room at the time – he had been “seized with a sudden attack and fell over a balcony of the window as he sought air.”88 That word was conveyed by his family and lawyer, disputing the notion of suicide. His attorney said, “He was worth seven to eight million dollars. He had no business nor family troubles.”89 A police detective and the assistant medical examiner, however, told the New York Times that he “fell or jumped.”

The idea that he had accidentally fallen was compromised by the fact that the window was “a narrow French one” with an aperture of only 15 inches. One pane opened inward and one outward. Dr. Auerbach, the assistant medical examiner, said, as worded by the newspaper, that “it was difficult to see how a man of the size of Mr. Lannin could have gone through the window without turning sideways and squeezing the body through.”90 The window sill was about three feet from the floor.91

Lannin had reportedly been in Room 915 to inspect plaster work that was being done at the hotel, and he had been attentive to the refurbishing of the newly purchased hotel, driving over just that morning from his residence at the Garden City Hotel. He had been in good spirits, his family said. He had asked his chauffeur to wait for him at the entrance and 15 minutes later a woman on the fifth floor saw him falling past her window.92

He was survived by his wife, Hannah, and their children, Paul and Dorothy.

Lannin is interred at the Cemetery of the Holy Rood in Garden City.

After his death, some came forth with stories of his generosity. The priest who gave the eulogy at his funeral, Rev. Francis J. Healey, reportedly recounted a story from a church service a few years earlier requesting assistance for a family that was having difficult times. Lannin went up to the priest afterward and said he wanted to help the family, but that it had to be completely confidential. “By the next morning, a truck load of food and clothing from the Garden City Hotel was delivered to the family in need.” The eulogy ended with Father Healey saying, “J.J. Lannin had respect for all people living their lives by their own honest convictions.”93

Another tale of generosity is told by Chris Parillo, the grandson of Louis and Carmella Parillo. Carmella’s father, Felice Eanaccone, had emigrated from Italy to the United States in 1906. Over time, he purchased some pieces of property in Westbury, Long Island. One such parcel was on Post Avenue, and the Parillos built a small shoe-repair shop on a portion of the land. Lannin was buying up land in order to build another luxury hotel and Eanaccone sold his parcel without realizing that it would mean the shop would have to close. “My grandmother paid a visit to Mr. Lannin at the Garden City Hotel, and basically pled her case. Mr. Lannin was well within his rights to just shoo her out of the office. Instead, he asked two questions: ‘How much do you think your building is worth?’ and ‘How much do you think you need for a down payment on another piece of property?’”

“He could have just asked her to leave, but he was a rags-to-riches guy. An immigrant. He came up from nothing. I think he said to himself, ‘I’m not going to deprive these people of their little piece of the American dream.’ He cut her a check. With that check, they were able to put a down payment on another piece of property up the street and build their own building, Louis Parillo Shoes.”94

Parillos own father inherited the store and Chris vividly recalled growing up in the shop that provided his family’s livelihood. “After he died, my grandparents put flowers on his grave once a week. I was born in 1968 and I remember as a little kid going to Holy Rood with my grandmother. My grandfather Louis Parillo died in 1963. He’s buried in the same row that Mr. Lannin’s buried. She would visit him and then she would visit Mr. Lannin. She lived until she was 96. She would go every week. I was 4 or 5. Forty-plus years later, she was still doing that.”95

J.J. Lannin had never forgotten his ties to his native land. As his great-grandson tells it, “Once he got established in Boston, he would send about $20 a month to Canada and one of his sisters was instructed to get nickels or whatever and distribute them to kids on the street, so they could go to a movie or a ballgame. He did that every single month throughout his life.”96

Other properties Lannin owned included the Great Northern Hotel and the Grenoble Hotel in New York City, and a winter home in Tarpon Springs, Florida. Just two weeks after his death, the Grenoble was sold by his estate. In August, Paul Lannin began to arrange the sale of the Lannin Realty Company’s holdings.

Later in 1928, the annual checkers tournament in Boston became the Joseph J. Lannin Memorial Tournament.97

Son Paul Lannin became a lyricist and musical composer of note. The year after his father’s death, he initiated a golf tournament in his father’s honor.98 130 West 44th St. when he was composing and arranging music with the likes of Ira Gershwin and Vincent Youmans. One of his musicals, Two Little Girls in Blue, ran on Broadway; he also took the show to London. Other Broadway shows included a musical comedy, For Goodness’ Sake, starring Adele and Fred Astaire, The Whichness of the Whatness of the Whereness of the Who, and the Ziegfeld Follies.99

Dorothy Lannin’s grandson Christopher Tunstall has taken on her role as family historian, a mantle passed down through his mother and father.

Joseph J. Lannin was named to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 2004; it was Tunstall who delivered the acceptance speech.

In April/May of 2012, Christopher Tunstall recreated the 410-mile walk that young Joseph Lannin took from Lac-Beauport, Quebec, to Boston in 1880. He hadn’t needed to stop and take up work along the way as Lannin had, but the journey took him 26 days, following as best he could the routes used by the traders of the late nineteenth century. “It was still pretty rugged,” he recalled. “Being able to make my journey and walk He roomed in my at great-the famous grandfather’s Lambs Club footsteps at was a tremendous spiritual journey for me.”100

Notes

1 “Red Sox President Got His Start as Bell-Boy,” Boston Herald, December 2, 1913: 7.

2 Glenn Stout and Richard A. Johnson, Red Sox Century (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 71. It was widely understood that the stock in the names of McAleer and McRoy was actually held by Ban Johnson and Charles Comiskey. For information on the sale, see “To Get Half Interest,” Washington Post, September 13, 1911: 8. In 1919 Johnson admitted as much in court testimony. See “Johnson Admits He Once Owned Portion of Boston Red Sox,” Chicago Tribune, September 12, 1919: 17.

3 “McAleer and McRoy Are Out,” Boston Globe, December1, 1913:1.

4 “McAleer and McRoy Are Out.”

5 “McAleer and McRoy Are Out.”

6 “Braves’ Park Will Be Greatly Enlarged,” Boston Herald, November 22, 1913: 9.

7 “Boston Man Likely to Control Red Sox Team,” Boston Herald, December 1, 1913: 1.

8 Red Sox Century, 88.

9 Lawrence J. Sweeney, “Royal Rooters an Angry Lot,” Boston Globe, October 16, 1912: 6.

10 For more details on the actual sale to Lannin, see “Ban Johnson Swings Big Deal for Boston Red Sox,” Washington Evening Star, December 1, 1913: 16.

11 Catherine Lannin is found in the 1871 census of Canada at St. Dunstan, indeed listed as an Irish immigrant but already widowed. The census indicated that she was unable to read or write. No occupation is indicated, but she lived with eight children: Thomas (20), Bridget (18), Margaret (14), John (12), Sarah (9), Ellen (6), Joseph (4), and Patrick (2).

12 Harvey T. Woodruff, “Joseph J. Lannin, Canadian ‘Bell Hop,’ Who Became Baseball Magnate,” Chicago Tribune, January 11, 1914: B3.

13 Christopher Tunstall, email to author, February 2, 2021.

14 “Joe Lannin a Bostonian,” Boston Globe, December 14, 1913: 37. The notion, on Wikipedia, that “Penniless, he had remarkably made his way from Lac-Beauport to Boston on foot” seems fanciful and unlikely.

15 Woodruff; “Joe Lannin a Bostonian.”

16 “Joe Lannin a Bostonian.”

17 The original document is available on Ancestry.com.https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/imageviewer/collections/2361/images/007327479_00042?tree-id=&personid=&hintid=&queryld=36845d8024f7493966b503b2ad59a2fe&usePUB=true&_phs-rc=yoG301&_phstart=successSource&usePUB-Js=true&pld=2084530

18 Woodruff.

19 “Joe Lannin a Bostonian.” One can find any number of advertisements for the Garden City Hotel in New York newspapers such as the New York Daily News and New York Tribune listing “Joseph J. Lannin, Prop.” See, for instance, the section of “Summer Resorts” on page 12 of the April 21, 1902, New York Daily News.

20 “Up-Jersey Resorts,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 28, 1899: 6. The following year, another New Jersey resort – the Essex-and-Sussex Hotel, situated on 500 acres at Spring Beach Lake – announced that Lannin had leased the hotel for a number of years. Lannin, the newspaper said, “by his past connection with the best-known resorts of the country, is well-known to the traveling public.” See “Essex-and-Sussex,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 17, 1900: 11.

21 “Fine New Maine Resort,” Boston Herald, June 26, 1903: 10.

22 “British Checker Masters Arrive,” Boston Herald, March 13, 1905: 3. Articles as late as 1911 show his ongoing involvement with checkers.

23 The 1913 Boston Herald article agreed. “Red Sox President Got His Start as Bell-Boy,”

24 “Joe Lannin a Bostonian.”

25 “Lannin Is Now Sox President,” Boston Herald, December 25, 1913: 7.

26 Arthur Constantine, “A City Without Its Baseball Team Is Not on the Map,” Boston Herald, December 28, 1913: 37. The title of the article was a quotation from Lannin. The article explores at some length Lannin’s comments on baseball at the time of his ascension to leadership.

27 “Lannin Refuses to Sit in Box at Ball Games,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, July 28, 1914: 11.

28 Former ballplayer and now veteran sportswriter Tim Murnane discussed some of the competition, taking a pro-management tack. See T.H. Murnane, “The Magnate Has More Consideration for the Men He Gathers Around Him Than the Players Have for the Man Who Takes All the Chances,” Boston Globe, March 1, 1914: 37.

29 T.H. Murnane, “Federal a Two-Club League,” Boston Globe, January 11, 1914: 111.

30 “Yankees to Get Boston Players,” New York Times, January 29, 1914: 7.

31 T.H. Murnane, “Speaker Stays with Red Sox,” Boston Globe, March 7, 1914: 4. There was reportedly a bonus paid Speaker as well.

32 “Flowers at Lannin’s Plate,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1914:15.

33 “Ray Collins Signs Two Years Red Sox Contact,” Boston Herald, March 12, 1914: 6.

34 “Pays Big Price,” Washington Evening Star, July 19, 1914: 57. “Lannin Sole Owner of Red Sox,” New York Times, May 15, 1914: 13. The Taylors retained ownership of Fenway Realty, as well as some preferred shares. In 1916 Paul J. Lannin served as vice president of the Red Sox and Thomas W. Lannin as business manager. See “New Red Sox Officers,” Washington Post, May 15, 1914: 9. All told, the cost of his purchasing the team was said to be $600,000. Thomas Lannin died in 1934. “Thomas W. Lannin,” New York Times, December 15, 1934: 13.

35 “Base Ball Briefs,” Washington Evening Star, May 29, 1914:15.

36 “Lannin Refuses to Sit in Box at Ball Games.” Knowing the players’ first names was not as simple as it might sound because newspaper sportswriters generally did not use them.

37 “Joseph J. Lannin in Game for Pleasure,” Washington Times, August 1, 1914: 12. Lannin added, “I didn’t buy the Red Sox with the idea of making big profits, although some persons may not believe me. I love baseball, and I believe that after thirty years of hard labor as a business man I am entitled to some amusement. If the club breaks even this year or loses some money I will feel satisfied, for I am trying to build up the team so that Boston fans will soon be able to boast of another world’s championship.”

38 “Timely Baseball Bits,” Hartford Courant, July 14, 1914: 17.

39 “Lannin Has Courage,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, July 31, 1914: 18. See “Lannin and Baker ‘Fan’ Moguls; Both Are Type of ‘New School,’” Washington Post, October 11, 1915: 8.

40 “Just Another Victory for ‘Pride of East Orange,’” Newark Evening Star, August 5, 1914: 13.

41 Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady, eds., Braves Field – Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond (Phoenix: SABR, 2015).

42 T.H. Murnane, “Bill Carrigan for 1915-1916,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1914: 7.

43 Bill Nowlin, ed., The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions (Phoenix: SABR, 2014).

44 Bozeman Bulger, “Red Sox Owner to Oppose All Plans for Peace,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 20, 1914: 17.

45 “Lannin Friend of Dove of Peace,” Detroit Times, November 3, 1914: 6.

46 “Lannin Is Opposed to Granting Peace,” Boston Herald, November 5, 1914: 7.

47 “Red Sox – ‘Red Sox Should Win the 1915 Pennant in the American League Race,’” Boston Herald, December 27, 1914:14.

48 For a discussion of the exemption, see Joseph J. McMahon Jr., “A History and Analysis of Baseball’s Three Antitrust Exemptions,” Villanova University, 1995, at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cqi?article=1264&context=msli.

49 “Lannin Predicts $2 Baseball if Feds Keep On,” Boston Journal, February 12, 1915: 1. Ticket prices at the time began at 25 cents and ranged up to $1.50 for a box seat.

50 T.H. Murnane, “Fenway Park Entire Season,” Boston Globe, January 21, 1915: 7.

51 “Jackson, of Naps, to Join Yankees,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 2, 1915: 12. We note that Joe Jackson did not become a New York Yankee. In August 1915 he was traded to the Chicago White Sox.

52 “Movie Man Travels with Red Sox Club,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 25, 1915: 12.

53 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Red Sox Berth Is No Joy Ride,” Boston Globe, May 29, 1915: 4.

54 The Red Sox finished 101-50 and the Tigers were 100-54. The Red Sox had played four games that ended in a tie.

55 “Braves’ Field to Be Loaned to the Red Sox,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 23, 1915: 9. The deal was the same – free use, with reimbursement only for actual expenses.

56 “May Refuse to Let Sox Play,” Boston Herald, October 2, 1915: 6. The issue was satisfactorily resolved. See Lawrence J. Sweeney, “400 Seats for Royal Rooters,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1915: 16.

57 “Phillies Blamed for Tour Fizzle,” New York Times, October 16, 1915: 12.

58 T.H. Murnane, “Players the Big Problem,” Boston Globe, December 16, 1915: 7.

59 “Details of Plan to Be Worked Out,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, December 16, 1915: 18. Lannin took ill at the meeting in Chicago but completed his committee work before a slow recovery. See “Training Card of Champion Red Sox to Be Rearranged,” Providence Evening Bulletin, December 28, 1815: 14.

60 “Lannin Cuts Players’ Pay in Contract for1916,” Chicago Tribune, January 9, 1916: B2.

61 He said, as one might expect, that he thought his employer’s offers were fair. He expected that everyone on the team would return. James C. O’Leary, “Thinks Sox Will All Sign,” Boston Globe, January 6, 1916: 7.

62 T.H. Murnane, “Fenway Park Prices Reduced,” Boston Globe, January 20, 1916: 7.

63 “Providence Grays Bought by Draper,” Hartford Courant, January 25, 1916: 16.

64 This meant his proposed salary would be cut from $18,000 to $9.000. One justification was that his average had declined for three consecutive years – from .383 to .363 to .338, and then to .322 in 1915). After he was traded to Cleveland, he led both leagues in 1916 with a .386 average.

65 One detailed account of the trade was Melville Webb’s: “Speaker Cost Cleveland More Than $50,000,” Boston Globe, April; 9, 1916: 1. The trade was a shock to the players on the team, who thought Carrigan was kidding them when he first broke the news. Webb was present when Carrigan told the team and wrote that “[n]o aeroplane bomb could have startled” the team more.

66 Stout and Johnson, Red Sox Century, 110.

67 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Wood Declines to Sign with Red Sox,” Boston Globe, July 28, 1916: 7.

68 Lannin had been “sound in his judgment of the team,” said a Boston Globe subordinate headline. See “Speakerless Red Sox Triumph,” Boston Globe, October 3, 1916:7.

69 Games One, Two, and Five were played at Braves Field, with attendance averaging 42,370.

70 The lone run Ruth gave up was a first-inning inside-the-park home run by Hy Myers in the first inning. Attendance was 47,373.

71 “Disgusted by Ban, Lannin to Retire from Great Game,” Atlanta Constitution, August 16, 1919: 13. The decision to leave baseball was not taken for at least a few months. T.H. Murnane offered words of praise for Lannin’s leadership. See “Nearly Ready for the World’s Series,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1916: 16. Lannin was, of course, “elated” that the Red Sox won the pennant. See “Lannin Praises Red Sox Spirit,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1916: 7.

72 Lynch, 41.

73 Stout and Johnson, Red Sox Century, 115. Lannin said that owning the ballclub was interfering with his health, citing his heart condition. See “Champion Boston Red Sox Are Sold,” New York Times, November 2, 1916: 14. A few days later, Lannin added, “Running a ballclub is not all pleasure, and I felt that I would enjoy the game that I am so fond of more as a spectator.” See T.H. Murnane, “Lannin Says He Is Out for Good,” Boston Globe, November 5, 1916: 16.

74 John J. Hallahan, “Champion Red Sox Club Sold to Frazee and Ward,” Boston Herald, November 2, 1916: 1.

75 Michael T. Lynch Jr., Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson, and the Feud That Nearly Destroyed the American League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland 2008), 40-41. Lannin had sold the Newark, New Jersey, ballclub a few days earlier.

76 Frederick G. Lieb, The Boston Red Sox (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 155. Lieb’s book was originally published in 1947 by G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

77 Frederick G. Lieb, 155.

78 “Fenway Park to Go Under Hammer,” Hartford Courant, February 10, 1920:10.

79 John J. Hallahan, “Red Sox Not Sold, Peace with Lannin,” Boston Globe, March 4, 1920: 8. Frazee sold the ballclub in 1923.

80 “Lannin Threatens to Quit the Game,” Washington Post, August 22, 1920: 18.81 “New Owners for Bisons,” New York Times, October 29, 1920: 22.

82 See in particular Chapter 2 in Bill Nowlin, Tom Yawkey – Patriarch of the Boston Red Sox (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018). For the sale to the Quinn group, see “Red Sox Are Sold for Over Million,” New York Times, July 12, 1923: 15.

83 The February 24, 1925, Boston Globe had a photograph on page 21 of a considerable number of men – almost all wearing hats despite being indoors – at the New American House in Boston, competing in the Joseph J. Lannin Tourney.

84 “This Club Has Four 18-Hole Courses,” Boston Globe, June 1, 1924:40.

85 “Navin Attacks Lannin, Ex-Owner of Red Sox,” Boston Globe, January 3, 1927: 1. Lannin emphatically denied he had ever given such bonuses; he also pointed out that he had not owned the team in 1917. See James C. O’Leary, “Navin’s Story Brings Denial from Lannin,” Boston Globe, January 3, 1927: 9.

86 “Famous Airplane Runway to Give Way to Great Polo Field,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1928: 9.

87 “Lannin Buys Granada, Big Hotel in Brooklyn,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1928: 23.

88 “Ninth-Story Drop Kills J.J. Lannin,” Boston Globe, May 16, 1928:1.

89 “Ninth-Story Drop Kills J.J. Lannin.”

90 “J.J. Lannin Killed by Fall at Hotel,” New York Times, May 16, 1928: 16.

91 “Lannin Plunges to Death at Granada,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 15, 1928: 1.

92 “J.J. Lannin Killed by Fall at Hotel.”

93 Author interview with Christopher Tunstall on December 3, 2020.

94 Author interview with Chris Parillo on December 15, 2020.

95 Parillo interview. The shop that was built in 1927 was ultimately sold in 1998, more than 70 years later.

96 Tunstall interview.

97 “Checkers Today for Lannin Memorial,” Boston Globe, November 12, 1928: 19.

98 Ralph Trost, “Lannin Memorial Pros’ Last Northern Chance for Gold and Glory,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 15, 1929: 31; Ralph Trost, “Pros Will Have Course in Best Condition for Lannin Memorial,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 3, 1931: 18. Paul Lannin died on September 8, 1953.

99 Email communication from Christopher Tunstall on December 20, 2020.

100 Tunstall interview.

Full Name

Joseph John Lannin

Born

April 23, 1866 at Lac-Beauport, QC (CA)

Died

May 15, 1928 at Broooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.