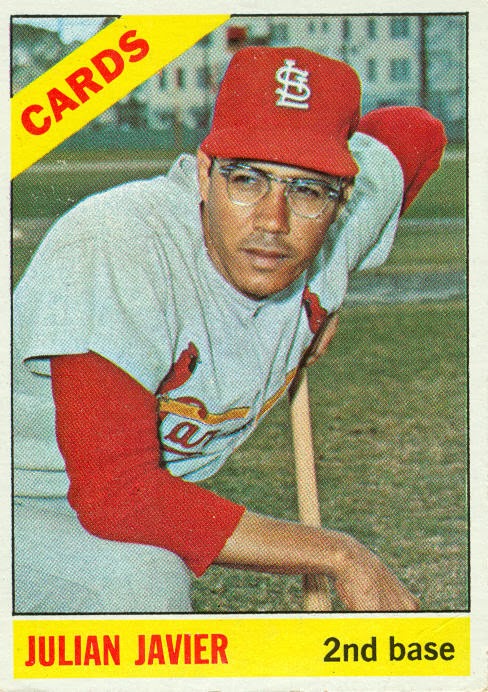

Julian Javier

Besides being a superb fielding but often light hitting second baseman with the St. Louis Cardinals for more than a decade, Julian Javier was a central figure in the history and development of baseball in the Dominican Republic.

Besides being a superb fielding but often light hitting second baseman with the St. Louis Cardinals for more than a decade, Julian Javier was a central figure in the history and development of baseball in the Dominican Republic.

Javier completed his playing days with a career .257 batting average. But in 19 World Series games, he batted .333 and belted a three-run home run in the 1967 Series. The bespectacled Javier also became one of the greatest defensive second basemen ever for the Cardinals, as well as one of the best bunters in baseball.

Manuel Julian Javier Liranzo, better known as simply Julian Javier, was born on August 9, 1936, in San Francisco de Macoris, Dominican Republic, which became his lifelong hometown. From 1960 to 1972, he played 12 seasons with the St. Louis Cardinals and one with the Cincinnati Reds. Tall and lanky at 6-feet-1 and 175 pounds, he batted and threw right-handed. A second baseman throughout his career, he won two World Series championships – 1964 and 1967 with the Cardinals– and played on two All-Star teams.

Son of a truck driver and the tallest of eight children, Julian developed his speedy running by racing other children to and from school – that is, when he wasn’t skipping school to listen to World Series broadcasts. In high school he played shortstop and batted cleanup, hitting .375. He learned to type nearly as fast as he could run, and considered a career in accounting or engineering. But when the Pittsburgh Pirates held a tryout in 1956 with 200 aspirants, scout Howe Haak persuaded Javier to set aside any other career choices and sign the only contract the Pirates offered that day, for only $500.1

Hampered by injuries, Javier’s professional career started slowly. But after three seasons working his way up the Pirates’ chain, he flourished at their Triple-A affiliate Columbus in 1959, leading the International League with 19 sacrifice hits and batting .274. The Baseball Digest scouting report on him for 1960 accurately described his coming major-league legacy: “Fastest man in league last year and has good range on grounders. Good arm and excellent hands. Fair hitter, but no power. Has good chance despite lack of power at plate.”2

Javier wanted to succeed quickly and said, “I want to build a home and need the money,”3 but the Pirates already had an all-star, golden glove second baseman in their lineup: future Hall-of-Famer Bill Mazeroski, who was four weeks younger than Javier.

Javier’s big break came on May 28, 1960, when the Pirates traded him and pitcher Ed Bauta to the Cardinals for veteran pitcher Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell and pitcher Dick Gray. The swap helped both sides, as Mizell helped the Pirates become champions in 1960, while the Cardinals had found their starting second sacker for the next 12 seasons.

Javier made his major-league debut the day of the trade, and got two hits against the San Francisco Giants. The Cardinals kept the deal secret until they posted their lineup. Even broadcaster Harry Caray did not hear about it until he reached the ballpark. Cardinals general manager Bing Devine surprised most observers by giving up a veteran starting pitcher for an unproven minor-league prospect; however, Eddie Stanky, the Cardinals’ director of player procurement, had insisted that Javier was one of the best he had seen.4

Julian, or Hoolie, as many called him by his rookie year, finished the season as the leadoff hitter. He batted only .237 and led the National League in errors with 24, but also led the league with 15 sacrifice hits, and in the field he showed good range and quickness, enough to be named to the Topps All-Rookie team.

A year later Javier continued to impress with his glove and sparked debates as to who was the fastest in the league, he or Vada Pinson. Commentators began to link him to great Cardinals second basemen Rogers Hornsby, Frank Frisch, and Red Schoendienst, all of whom won championships with the Redbirds.5

Javier returned to his home country during offseasons to hunt, work on his farm, and play winter ball. He got in trouble in early 1963 for participating in exhibition games not authorized by major-league teams and was fined $250 by Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick. Under their agreement with Frick, winter-league teams agreed not to sign any players from the US without their team’s approval, and Latin players would play in their home countries only in regularly organized and pre-approved games.

Javier improved his batting average over 40 points to .279 in 1961, and hit .263 in both 1962 and 1963. He posted career highs in stolen bases (26) and runs scored (97) in 1962. He led the league in putouts by a second baseman two years in a row with 377 in 1963 and 360 in1964.

In 1963, when Bill Mazeroski dropped off the All-Star roster due to an injury, Javier completed an all-Cardinals starting All-Star infield, with Bill White at first base, Dick Groat at shortstop, and Ken Boyer at third base. He also played in the 1968 All-Star Game.

Bothered by a sore back in 1964, Javier nonetheless managed to play in 155 games in the Cardinals’ championship season, with 12 home runs and a career-high 65 RBIs. His batting average dropped to .241, and he once again led the league in errors with 27. A sore hip limited his World Series efforts to only the first game, in which he had no plate appearances, pinch-ran and scored a run, and played two innings in the field. Dal Maxvill played second base in place of Javier.

The injuries continued to limit Javier the next two seasons, and his offensive performance diminished to its lowest point with the Cardinals. He batted .227 in only 77 games in 1965, then .228 in 147 games in 1966. He faced losing his starting job to versatile utility fielder Jerry Buchek, who could play second, third, and short.

Javier started 1967 with some major changes. He added 10 pounds in weight, employed new wrap-around glasses, and picked up a heavier bat, going from a 31- to a 35-ounce one. During spring training bullpen coach Bob Milliken threw curve after curve to him, working to control Javier’s tendency to bail out on tough right-handed pitchers. The changes paid early dividends as he opened the season with a seven-game hitting streak and a .407 average.

Manager Schoendienst noticed the obvious improvement, saying, “Hoolie’s been watching the ball a lot better. I think his new glasses might be helping as much as anything. He’s been taking the bad pitches he used to swing at, especially those balls outside.”6

The good returns continued throughout the season, as Javier stayed healthy and produced one of his best offensive seasons, with a .281 average (.325 against left-handers) in 520 at-bats, and a career-high 14 homers. He finished ninth in voting for the National League Most Valuable Player award, as he helped propel the Cardinals into the postseason for the second time in four years.

In July 1967 a double play started by a little tap Javier hit back to the pitcher led to a spontaneous quip by Cardinals broadcaster Jack Buck. The 1-6-3 play went from pitcher John Boozer to shortstop Bobby Wine to first baseman Tony Taylor, but Buck reported, “That double play went from Boozer to Wine to Old Taylor.”7

The Cardinals followed Bob Gibson’s pitching to beat the Boston Red Sox in the first game of the 1967 World Series. In the second game, a 5-0 Cardinals loss, Javier broke up Jim Lonborg’s no-hitter in the eighth inning with a double to the left-field corner with two outs. Lonborg went on to surrender only Javier’s hit in a complete-game shutout.

After two more wins by each team, the World Series went to a Game Seven. In the sixth inning of that deciding game, Hoolie smashed a three-run home run off Lonborg and ensured Bob Gibson’s third Series victory and St. Louis’s second championship in four years. Javier’s renewal from the beginning of the season carried through to the end, as he compiled a .360 batting average in the Series.

Javier returned to his native Dominican Republic a national hero. President Joaquin Balaguer conferred on him the Order of the Fathers of the Country, the country’s highest decoration.8 The Pittsburgh Pirates played an exhibition game against Dominican stars in Santa Domingo about a week after the Series ended, with natives Matty Alou and Manny Mota and Puerto Rico native Roberto Clemente, but the biggest welcome of the day went to the Cardinals’ second sacker.9

The Cardinals won the pennant again in 1968 but Javier’s batting average dropped 21 points, to .260. He played in the All-Star Game that season. Despite his .333 batting average in the 1968 World Series, the Cardinals lost in seven games to the Detroit Tigers.

Javier’s average rebounded in 1969 to a personal best of .282, and he continued as a Cardinals starter through 1970. Early in the 1971 season, Javier returned to the Dominican Republic to be with his brother, Luis, who died while he was there. His playing time lessoned considerably that season, as he started only 68 games at second base, yielding a major part of the playing time to Ted Sizemore.

Javier’s orientation to professional baseball in the US did not include a full understanding of his obligations to the Internal Revenue Service. In October 1970 the IRS filed tax liens against him for as much as $84,320, covering tax years of 1961 and 1963 through 1969. His annual salary came to an estimated $50,000 at the time. When he received word of the proceedings, he had already returned home to the Dominican Republic. The unresolved debt jeopardized his return to the US to play in 1971.10 Apparently he had received no advice, or perhaps misguided information, as he had filed no tax returns for several years. He thought the withholding from his paycheck satisfied his obligations.11 He employed a lawyer, settled the debt for considerably less than the original claim, and arrived in Florida in 1971 in time for spring training.12

In March, 1972, the Cardinals traded the 35-year-old Javier to the Cincinnati Reds for pitcher Tony Cloninger. He became very much a part-time player, starting only 17 games for the World Series-bound Reds, now playing mostly third base and batting only .209. Still a contributor until the end, Javier started at second base in the final regular-season game of his career, on October 1. In his last regular-season at-bat, he bunted to help set up the only run of the game in a Reds 1-0 win over the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Javier played in his fourth World Series with the Reds that season. His sacrifice bunt in his very last plate appearance contributed to a run for the Reds in Game Four, as the Reds fell to the Oakland Athletics in seven games. The Reds released him two days after the Series ended.

Without a job in the big leagues, Javier headed home to the San Francisco de Macoris, where he began to organize a professional franchise to compete in the Dominican winter league. He took a turn at managing in 1974 with the Yucatan Leones of the Mexican League, then returned home to stay with family and to help further develop baseball in his home country. To give youngsters a good start in baseball, he founded the Dominican branch of the Khoury League, later renamed the Roberto Clemente League to honor the Pirates legend.

In 1975 Javier put together a summer league of four teams that competed in his home territory. He and his son Stan teamed to form the Gigantes del Cibao, which became one of the regular contenders in the Dominican winter league. He was chosen the all-time second baseman for the Aguilas Cibaeñas, and his number (25) was retired by the Dominican Winter Baseball League.

Julian Javier built has major-league career largely around his speed and slick glove. Multiple sources rated him as the widest-ranging second baseman in the league, largely due to his great speed and quickness. His especially long fingers reminded many of a concert pianist, yet he said, “They help me in typing.”13

Gene Mauch called Javier “the greatest I ever saw on getting pop files and as good as anyone on coming in on a ball.” His middle-infield partner, Dal Maxvill, considered him one of the best ever, especially at going to his right. “I’ve never seen that play made by anyone else,” Maxvill said. “I’m spoiled if he doesn’t make it.” On slow grounders, Maxvill said, “he goes in low, doesn’t straighten out and fires the ball with something on it. I’ve seen him throw just this far [six inches] off the ground.”14

Javier earned another nickname, the Phantom. Orlando Cepeda pointed out his smooth moves around second base: “Hoolie comes out of nowhere like a phantom.” Maxvill said, “Hoolie’s like a ghost out there. Runners try to nail him, but he gets the throw off so smoothly – and then he disappears.”15

Javier combined his speed and stick skills to become rated one of the league’s best bunters. He ranked first or second in sacrifice hits three out of his first four years with the Cardinals. He also produced the rare combination of a skillful short game and a surprising ability to hit the long ball, especially in clutch situations. His three home runs hit in 1-0 games place him in a tie with many others for sixth all-time, behind Ted Williams, who had five, and four others with four.16

Javier often surprised with his sudden displays of oomph, like the grand slam he hit in 1961 on his 25th birthday to beat the Pirates, 4-0. In May 1964 the Cardinals rode his three-run homer to victory over the Phillies, 3-2. That day he claimed he had stuffed himself with vitamins given to him by his brother, who was a doctor. Four days later he hit a grand slam and ended the week with 12 runs batted in.17 In July 1969 he launched a ball to the roof of Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia, after which he said, “I didn’t eat any breakfast, and all I ate before going to the park was a small salad. If I had eaten a big salad, I would have hit the ball over the roof and out of the park.”18

Javier’s batting average fluctuated greatly from year to year, partly due to injury but also because of other factors such as pitch selection. According to batting coach Dick Sisler, the better numbers seemed to come when he refused to swing at bad pitches, especially low and outside sliders and curves from right-handed pitchers.19

Sisler saw a major constant in Javier’s statistics: He always hit much better against left-handers than against right-handers (.299 lifetime against lefties,.233 when facing righties). In three seasons (1965, 1968, and 1970) the gap amounted to more than 150 points in batting average against left-handers. The old stalwart Branch Rickey suggested once that Javier might become a really great hitter if he learned to switch-hit, but Javier continued to hit from one side of the plate.20

An incident in February 1964 in the Dominican Winter League involving Javier and umpire Emmett Ashford, then a nine-year veteran of the Pacific Coast League, played a major role in vaulting Ashford through the racial barrier to become the first African American umpire in the major leagues. With Javier at bat, Ashford called two strikes on him on low outside pitches, Javier’s common nemesis at the plate. He protested the calls, saying, “Why you call the pitch on me? You know I don’t like that pitch.”

“Why the hell do you think he’s throwing it?” answered the ump.

Javier shot back: “Oh, a comedian!” Ashford told Javier to get quiet and bat. As Javier stepped back in, he took a called third strike right down the middle of the plate. He turned in protest and landed a punch on Ashford’s jaw.21 The umpire responded with a couple of his own shots, using his mask and actually drawing blood. The fans “could have strung me up on the spot,” remembered Ashford. “But they were with me, and I think that’s what put me over the top.”22

Javier received an indefinite suspension at first, but the penalty was quickly reduced to three days and a $50 fine because of the Dominican’s popularity. Ashford’s first reaction led him to resign from the Dominican league for the rest of the season. He finally relented when Javier apologized on the radio. Soon afterward, American League president Joe Cronin purchased Ashford’s contract, apparently convinced that he knew how to face difficult situations. The popular Ashford then made history in his American League debut on Opening Day, 1966, in Washington.

Among his seven children, Javier’s son Stan, named for Cardinals great Stan Musial, played major-league baseball for 18 seasons with eight different teams. Another son, Julian J. Javier, developed a noted medical practice as a cardiologist in Naples, Florida. A third son, Manuel Julian Javier, became an engineer in Santiago, Dominican Republic.

Estadia Julian Javier, the stadium in San Francisco de Macoris, was built as a namesake tribute to one of the pioneer Dominican major leaguers. It became both the home of the Gigantes del Cibao, the baseball team he formed, and a crown to the popularity and success of Manuel Julian “Hoolie” Javier Liranzo.

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Neal Russo. “Javier Something Special with Bat as Well as Glove.” The Sporting News. September 2, 1967.

2 Herbert Simons. “Scouting Reports on 1960 Major League Rookies.” Baseball Digest. March 1960.

3 Jack Herman. “Cards Find Comet in Swifty Javier.” The Sporting News. June 15, 1960.

4 Herman. “Redbirds Boost Firepower with Changed Lineup.” The Sporting News. June 8, 1960.

5 Russo. “Swift Keystoner Rated Key Man in Redbirds Future; Cuts Down on Strikeouts.” The Sporting News. August 23, 1961.

6 Russo. “Hoolie’s Hot Bat Fuels Redbird Takeoff.” The Sporting News. May 6, 1967.

7 “Boozer-Wine-Old Taylor Knocks Cards on Ears.” The Sporting News. July 8, 1967.

8 “Dominican Republic Gives Hero’s Welcome to Javier.” The Sporting News. November 4, 1967.

9 Fernando Viscioso. “Pirates Defeat Native Stars Before 19,152.” The Sporting News. November 4, 1967.

10 Russo. “$84,320 U.S. Tax Liens Brought Against Javier.” The Sporting News. October 17, 1970.

11 Russo. “Javier Figures in ’71 Redbird Plans.” The Sporting News. January 30, 1971.

12 “Bunts and Boots – Javier Tax Settlement.” The Sporting News. April 3, 1971.

13 “Baseball’s Week.” Sports Illustrated. July 8, 1963.

14 Russo. “Hoolie’s Hot Bat Fuels Redbird Takeoff.” The Sporting News. May 6, 1967.

15 Russo. “Redbird Phantom Striking Dread in Hearts of Enemies.” The Sporting News. August 23, 1969.

16 Lyle Spatz, ed. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book. New York: Scribner, 2007.

17 “Baseball’s Week.” Sports Illustrated. May 25, 1964.

18 “Baseball’s Week.” Sports Illustrated. July 21, 1969.

19 Russo. “Redbird Phantom.” Op cit.

20 Bob Broeg. “All-Star Team of Switch-Hitters.” The Sporting News. February 17, 1979.

21 A. S. “Doc” Young. “Ashford Was One Ump with Box-Office Appeal.” The Sporting News. December 26, 1970.

22 Joe Falls. “The Ump GETS This Decision.” Baseball Digest. July 1966.

Full Name

Manuel Julian Javier Liranzo

Born

August 9, 1936 at San Francisco de Macoris, Duarte (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.